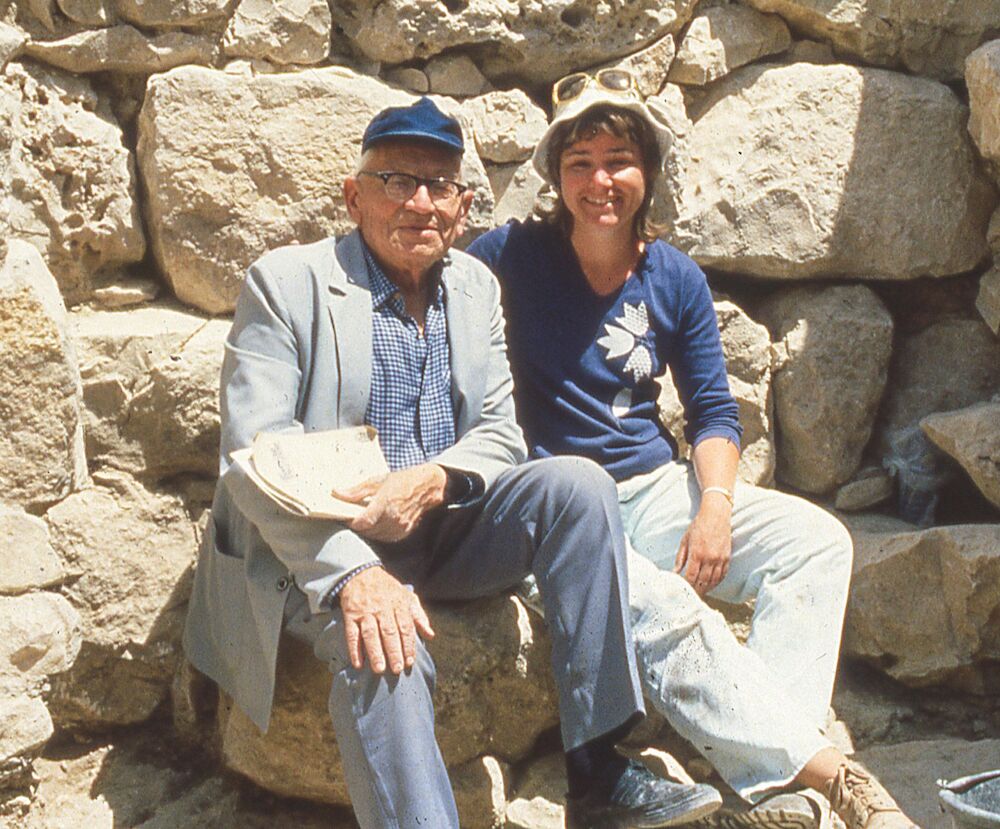

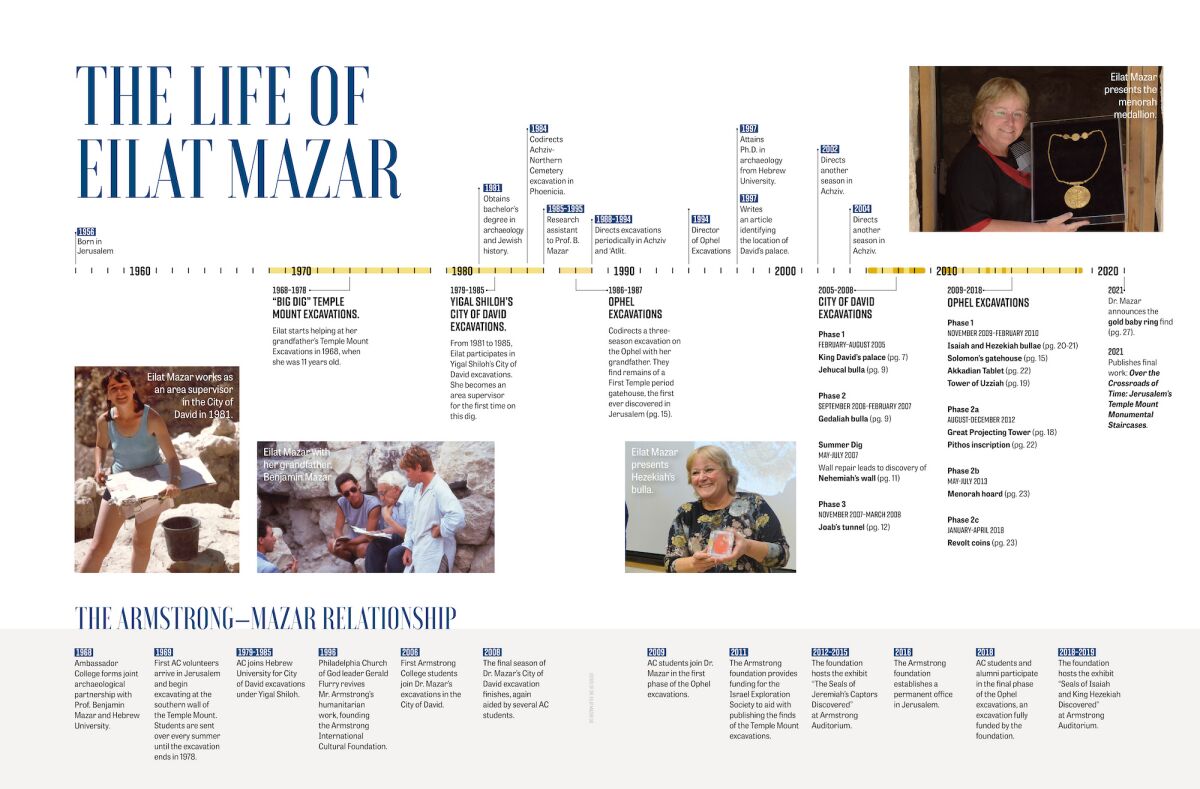

Dr. Eilat Mazar excavated Jerusalem for over 50 years. Born in Jerusalem in 1956, Eilat began her archaeological career at age 11, when she worked alongside her grandfather, the late Prof. Benjamin Mazar, on his Temple Mount excavations.

Benjamin Mazar was a founding father of the modern Jewish state. He was central to the establishment of Hebrew University and the Israel Exploration Society, as well as numerous other intellectual and public institutions in Israel. One of Eilat’s favorite childhood memories was attending the weekly gathering hosted by her grandfather in the living room of his home in Jerusalem. Many of Israel’s top scholars, scientists and politicians attended these meetings where they would discuss Israel’s history and new ideas and projects for the nation. Together with her sister (Avital), young Eilat served tea and coffee to the older scientists and statesmen who attended these meetings.

When Eilat finished her mandated stint in the army, she literally ran to the admissions office at Hebrew University. There, she studied archaeology and Jewish history.

In 1981, after attaining her bachelor’s degree, Eilat participated in Prof. Yigal Shiloh’s City of David excavations, which lasted from 1981 to 1985. Within a few weeks of starting work, Eilat had moved from assistant area supervisor to area supervisor. During her time working for Professor Shiloh, Eilat talked frequently with her grandfather.

“What’s new at the excavation?” he would ask each day.

“What’s new? We just discussed all the new things yesterday, so what can be so new?” she would reply.

“No, no, no; what’s new?” her grandfather would ask again.

“He was expecting new and fresh thinking every single day,” Eilat later recalled. “He really pushed me. On the one hand it was quite distressing, but on the other hand it pushed me to constantly be thinking every time that I am excavating.”

In 1986, Eilat convinced her grandfather to return to the field and join her as codirector of a small excavation at the southernmost area of the Ophel. Benjamin agreed and almost immediately the pair discovered remains of a First Temple period gatehouse (the first ever discovered in Jerusalem).

In 1997, Dr. Mazar attained her Ph.D. from Hebrew University following a comprehensive pioneering study about the biblical Phoenicians based on her ongoing excavations (which began in 1984) at the key Phoenician site of Achziv (in northern Israel).

That same year, Dr. Mazar wrote an article for Biblical Archaeology Review suggesting a possible location for King David’s palace. Her hypothesis was based on 2 Samuel 5:17, which says King David “went down to the fortress” in preparation for a Philistine invasion. Based on this scripture and other evidence, Mazar posited that King David’s palace was likely located in the northern part of the City of David. “If some regard as too speculative the hypothesis I shall put forth in this article,” wrote Dr. Mazar, “my reply is simply this: Let us put it to the test in the way archaeologists always try to test their theories—by excavation.”

Eight years later, Dr. Mazar finally received funding to excavate the City of David in 2005. Within weeks, she had uncovered massive walls, indicating the presence of a large structure, which dated to King David’s period.

Dr. Mazar conducted three phases of excavations in the City of David between 2005 and 2008. She uncovered more evidence of David’s palace, as well as other remarkable artifacts supporting the biblical record, including a portion of Nehemiah’s hastily constructed wall (Nehemiah 6:15) and the seal impressions of Jehucal and Gedaliah—two biblical princes (Jeremiah 37:3 and 38:1) who opposed the Prophet Jeremiah.

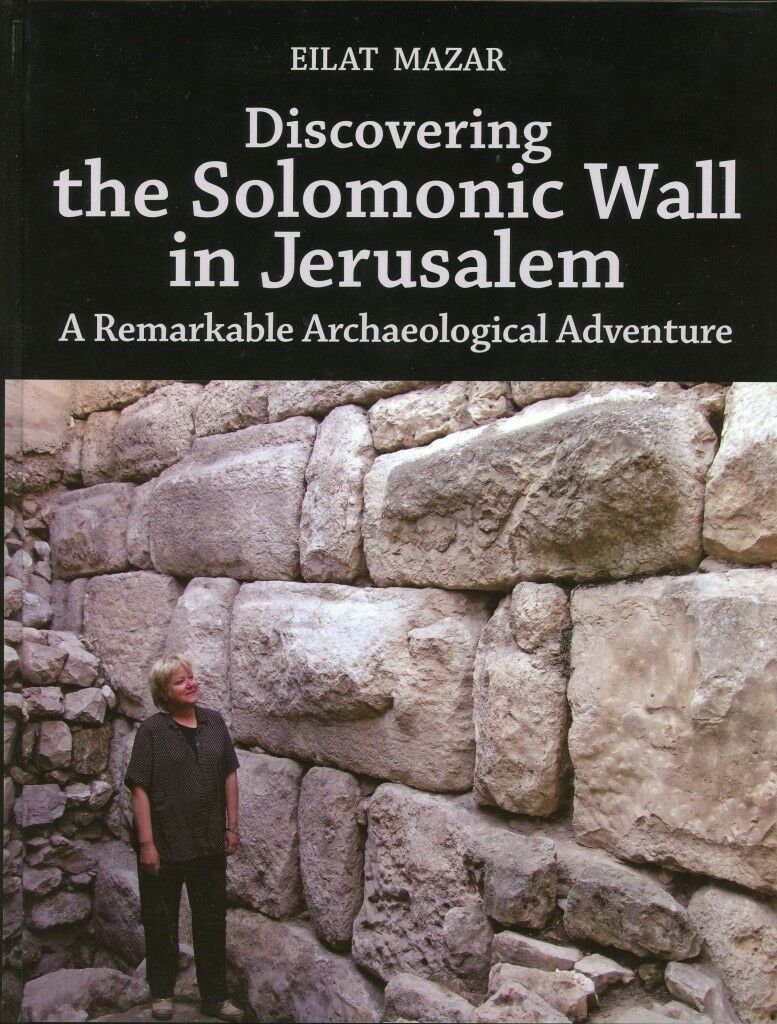

In 2009, Dr. Mazar returned to the Ophel to excavate. This dig and three other excavations (2012, 2013, 2018) uncovered more extraordinary history. The Ophel discoveries included a massive city wall from King Solomon’s time, the Menorah Medallion treasure, dozens of coins relating to the first-century Jewish revolt, and two biblical seal impressions: one belonging to King Hezekiah of Judah, the other belonging to Isaiah.

Throughout her career, Dr. Mazar always relied on the Bible to guide her work. “One of the many things I learned from my grandfather was how to relate to the biblical text,” she recalls. “Pore over [the Bible] again and again,” her grandfather had said, “for it contains within it descriptions of genuine historical reality.” To Eilat, using the Bible as an archaeological handbook was simply common sense:

Archaeology cannot stand by itself as a very technical method. It is actually quite primitive without the support of written documents. Excavating the ancient land of Israel and not reading and getting to know the biblical source is stupidity. I don’t see how it can work. It’s like excavating a classical site and ignoring Greek and Latin sources. It is impossible.

Unsurprisingly, Dr. Mazar’s reliance on biblical history meant frequent clashes with skeptical colleagues. One outspoken critic of her work was Israel Finkelstein, a professor at Tel Aviv University. In response to Mazar’s discovery of the huge “Solomonic Wall” on the Temple Mount, Finkelstein wrote, “Had it not been for Mazar’s literal reading of the biblical text, she never would have dated the remains to the 10th century b.c.e. with such confidence.” Many other scholars have made similar critical remarks.

Contrary to the claims of her critics, however, Dr. Mazar pursued her work with unimpeachable scientific rigor (To learn more, read “Defending Eilat Mazar—and the Biblical Record”). Eilat always aimed to be more loyal to science, to the truth, than her own theories. On one occasion, she even publicly admitted to misreading an inscription after epigraphers who had viewed the artifact online questioned her interpretation. Instead of digging in her heels, she told the critics how happy she was that the Internet facilitated scholarly collaboration.

Dr. Mazar was not an agenda-driven ideologue seeking confirmation of her religious fanaticism in the rubble of Jerusalem. Instead, she strove to “let the stones speak”—and was willing to listen to whatever they had to say:

You can have all theories and working hypotheses as you go to the field, but the minute you start to excavate, all these theories need to be put on the side. From that minute onward, you have to document and give every little item a precise height and photograph what you find. … I think that the people who get to know the details of how archaeology works nowadays understand that you cannot force agenda on the facts.

One testament to Dr. Mazar’s unbiased approach was the fact that she often invited other archaeologists, especially those who disagreed with her, to tour her dig sites. Notably, during the 2006 season of the City of David excavations, Dr. Mazar gave Professor Finkelstein a tour of her site. “Everybody is most welcome to observe how we work, and afterwards, how we process the finds,” she said. “We make sure that everything can be observed and criticized. Then nobody can blame us that we are not doing the best updated work.”

In short, Dr. Mazar was a diligent pursuer of historical truth. The profuse criticism she attracted resulted almost exclusively from her belief in the Bible, as the late editor of Biblical Archaeology Review Herschel Shanks said: “No one would question [Dr. Mazar’s] professional competence as an archaeologist. Her chief sin, however, is that she is interested in what archaeology can tell us about the Bible” (emphasis added).

After a three-year battle with serious illness, Dr. Mazar died on May 25, 2021. Her 50-year archaeological career was impressive. She participated in or directed five major excavations, authored 12 books, and coauthored several more. Dr. Mazar made some of the most astonishing finds in the history of biblical archaeology (read here, here, and here). Through it all, she followed in the footsteps of her grandfather, maintaining a close relationship with the Armstrong International Cultural Foundation (the parent organization of the Armstrong Institute of Biblical Archaeology).

With the benefit of hindsight, even some of Dr. Mazar’s staunchest critics are beginning to recognize the significance of her legacy. “Eilat Mazar’s impacts on the archaeology of Israel in general and Jerusalem in particular will always be counted among the cornerstones of the archaeology of Israel,” said Professor Finkelstein. “She will be greatly missed.”

“Eilat will forever be remembered as a pioneer standing shoulder to shoulder with the greatest scholars of Jerusalem throughout the ages,” said David Be’eri, ceo of the City of David and longtime friend of Dr. Mazar. Another of Eilat’s close friends, editor in chief of Let the Stones Speak Gerald Flurry, put it this way: “There are some very talented archaeologists in the world, especially in Jerusalem. But I believe Dr. Mazar will be remembered as one of the greatest archaeologists of all time.”