“To illustrate the Bible”—that was the calling card of biblical archaeology in its formative years. This sentiment was perhaps most notably articulated in an 1865 speech delivered by Archbishop William Thomson at the first meeting of the Palestine Exploration Fund (pef). Readers of the Bible were thousands of years—and thousands of kilometers—removed from places and events described. The work of biblical archaeologists was “not … to launch controversy” (ironic, given the last century and a half of debate)—but rather to “apply the rules of science … to an investigation into the facts concerning the Holy Land.”

“[N]o country more urgently requires illustration,” he said.

Of course, Thomson was speaking figuratively of the intent to bring the Bible to life for readers, through discovery and excavations of locations and events relevant to the biblical account. Certainly, there would have been little thought of literal illustrations of the famous biblical rulers of the Holy Land.

Yet that is what we now have—a growing body of likely and near-likely contemporary depictions of actual rulers of Israel and Judah.

You’ve read about them—now you can see them.

Jehu

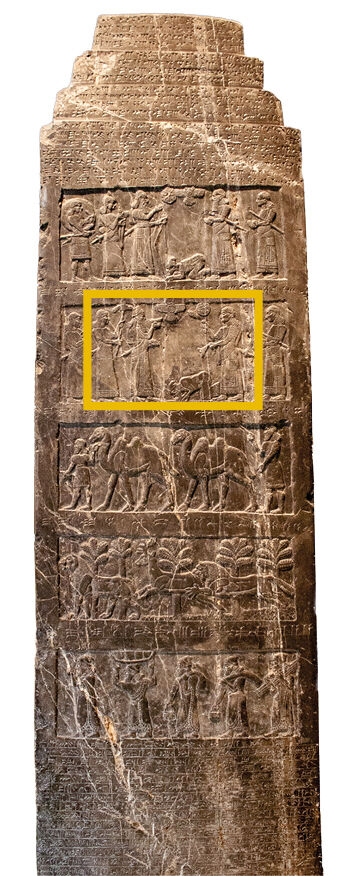

The Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser iii is one of the most famous artifacts in biblical archaeology. Found in Nimrud (northern Iraq) in 1846 and displayed prominently within the British Museum, this nearly 2-meter-tall artifact, dating to circa 825 b.c.e., is covered with 20 panels depicting subdued kings and tribute being brought before the Assyrian king.

During this time, Jehu was ruler of Israel (circa 842–815 b.c.e.). The inscription directly mentions him, and another king of Israel: “The tribute of Jehu, son of Omri: I received from him silver, gold, a golden bowl, a golden vase with pointed bottom, golden tumblers, golden buckets, tin, a staff for a king [and] spears.”

This text serves as header to a panel below, depicting the king offering the tribute in question. “The submission of [Samaria] is shown … where ‘Jehu, son of Omri’ bows before Shalmaneser” (Encyclopedia Britannica, “Shalmaneser iii”).

Jehu, per the biblical account, is clearly not a “son of Omri”; instead, he rose to power in a coup and ended the Omride dynasty. This surely would have meant little to the Assyrian king (who may not have been aware of political wranglings within Israel). In fact, the standard Assyrian name for “Israel” was “House of Omri”—a territorial name that continued into the late eighth century b.c.e., when the land of Israel was finally conquered and the residents taken captive.

For more on Jehu, his depiction on the Black Obelisk, and the crucial role this artifact plays for biblical chronology, read “The Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser and the Earliest Depiction of an Israelite” and “Dating the United Monarchy to the 10th Century B.C.E.”

Manasseh

Judah’s King Manasseh was the longest-reigning king of either Israel or Judah (2 Kings 21:1). His 55-year reign spanned most of the first half of the seventh century b.c.e. (circa 697–642 b.c.e.). He is famous for his rank rebellion against God—worse than all who came before him—even “worse than the heathen, whom the Lord had destroyed before the children of Israel” (2 Chronicles 33:9; King James Version). As a result, partway through his long reign, Manasseh was taken captive by “the king of Assyria, which took Manasseh among the thorns, and bound him with fetters, and carried him to Babylon” (verse 11; kjv).

This unusual language actually refers to hooks placed in the nose, mouth or cheeks. The Jewish Publication Society translation reads, more generally, “took Manasseh with hooks”; the Amplified Bible says, “they captured Manasseh with hooks (through his nose or cheeks) … and took him to Babylon” (for more detail, see “King Manasseh’s ‘Nose Hooks,’ in the Bible and Archaeology”). The account then describes Manasseh’s repentance while in captivity, and his later reinstallment in Jerusalem.

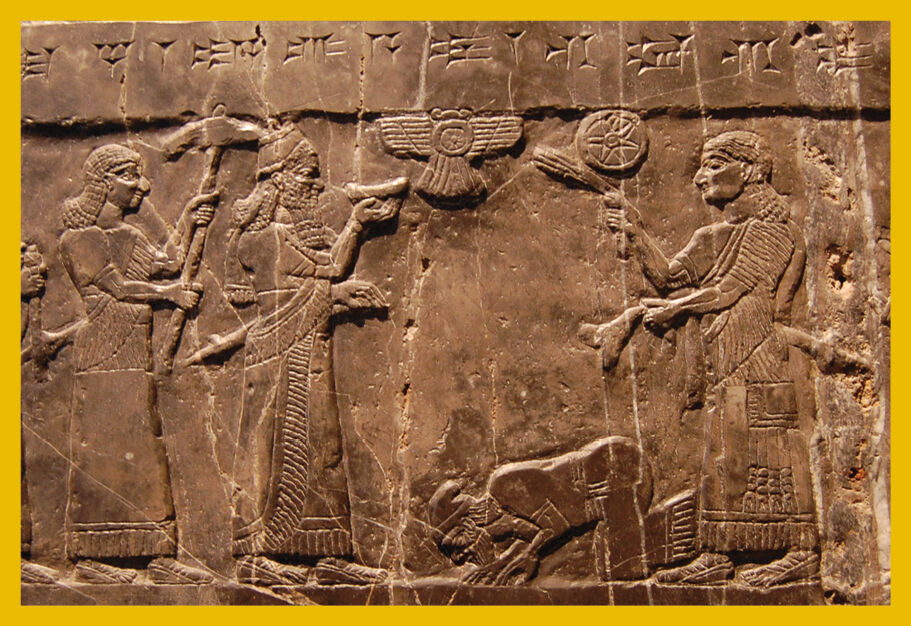

The biblical account does not name the Assyrian king responsible for Manasseh’s imprisonment, but it is a good chronological fit with the reign of Esarhaddon. From his reign, we have a massive 3.5-meter-tall victory inscription, the Victory Stele of Esarhaddon, which commemorates his victories in Egypt in 671 b.c.e. (the stele was constructed soon after).

The stele, discovered at Zincirli Höyük (southern Turkey) in 1888 and on display in Berlin’s Pergamon Museum, is covered with cuneiform text describing Esarhaddon’s vengeance against Kushite-ruled Egypt, governed by Pharaoh Taharqa, a figure mentioned elsewhere in the biblical account (2 Kings 19:9; Isaiah 37:9). The stele text is directly carved onto a prominent depiction of a larger-than-life Esarhaddon. He stands above two much smaller captive rulers, holding onto them by a leash. The smaller figure is a Kushite, Prince Ushankhuru (son and heir of Taharqa), whom Esarhaddon describes as being carted away. (An alternate opinion is that this represents Taharqa himself.)

Of more interest for our purposes is the slightly larger, unnamed standing figure. Based on his appearance, this is clearly a Levantine ruler. Varying theories include identifying him perhaps with either a Phoenician ruler of Sidon (Abdi-Milkutti) or of Tyre (Baal i). Yet this is only speculative, as neither king nor territory is mentioned on the stele. (Besides Egypt, Esarhaddon only speaks more generally about subduing “unsubmissive princes.”)

A closer inspection of the face of this Levantine king reveals it to have been apparently pierced through with some kind of hook or ring and attached to the leash that the Assyrian king is holding.

Which Levantine king could this be other than the very one described as having been hooked through the face by an Assyrian king and led away captive around this very time? This would be about midway through King Manasseh’s reign. And while the primary focus of the victory stele’s inscription is Assyria’s defeat of Egypt, other inscriptions of Esarhaddon mention Manasseh, including payment of tribute from this king of Judah. It is easy to imagine a scenario in which the Assyrian army passed through the land of Judah on the way to or from battle with Egypt, demanding recompense from the Judahite king for perhaps failing to meet tributary requirements. And the sense from the biblical text is that Manasseh was simply handed over, rather than forcibly taken via prolonged siege.

For more on Manasseh and Esarhaddon, read “King Manasseh’s ‘Nose Hooks,’ in the Bible and Archaeology” and “Esarhaddon Prism Proves King Manasseh.”

Jehoash

Kuntillet Ajrud is a peculiar Iron Age outpost located within the Sinai. While this site is technically closer to the territory of the kingdom of Judah, it bears more connection with the kingdom of Israel, based on inscriptions discovered at the site, as well as in iconography. There is even an inscription referencing “Yahweh of Samaria.” As such, site excavator Ze’ev Meshel (1932–2024) believed the outpost to have operated under the control of the northern kingdom of Israel, rather than Judah. The single-use site operated during a very brief period around 800 b.c.e.

The king of Israel on the scene at this time was Jehoash (805–790 b.c.e., also spelled Joash)—predecessor to the perhaps better-known Jeroboam ii. It was during Jehoash’s reign that significant conflict took place with Judah’s King Amaziah, in which the Judahite king was beaten back, Jerusalem besieged, and the temple ransacked (2 Kings 14; 2 Chronicles 25)—thus giving Jehoash de facto control over the southern kingdom, also helping to explain the Israelite presence at this single-use Sinai outpost southwest of the kingdom of Judah.

Among the circa 800 b.c.e. inscriptions and drawings found at Kuntillet Ajrud was a painted plaster portrait, generalized as depicting a seated Near Eastern king. The late Prof. Pirhiya Beck, in a posthumously published article, went further, identifying this as a “king of either Israel or of Judah” (“The Art of Palestine During the Iron Age ii”). Based on this as an Israelite site—and more specifically, Meshel’s association of it with King Jehoash’s reign—could this be a representation of the very king? The identification would make sense based on the tight dating window and geopolitical situation.

The 32-centimeter-high plaster painting shows a royal figure depicted in typical kingly style, seated on a throne and holding a lotus flower. This is a royal motif of Egyptian origin, commonly found in Near Eastern artwork. A parallel example of a Levantine king symbolically holding a lotus flower was unearthed in Amman in 2010—in this case, a monumental statue of an Ammonite king dating to the eighth century b.c.e. Another example is a depiction of a seated Phoenician king portrayed on the Ahiram Sarcophagus (10th century b.c.e.). There are other examples cited by Beck.

For more on Jehoash and his potential depiction at Kuntillet Ajrud, read “Is This the Biblical King Jehoash?”

Ahab?

Abel Beth Maacah is an ancient site located in Israel’s far north, adjacent the border of Lebanon. This site likewise sat on ancient Israel’s far northern border. The geographic location has prompted long debate as to when and whether this site came under Israelite control, versus Phoenician or perhaps Syrian control. As early as the reign of David, the biblical account mentions “Abel of Beth-maacah” as a “city … in Israel” (2 Samuel 20:15, 19).

One particular discovery at the site made headlines in 2020: a vessel dating to the 10th to ninth centuries b.c.e., bearing the inscription “Belonging to Benayau.” Not only was this an Israelite name, with a theophoric element referring to the God of Israel, it also was spelled in a manner particular to the northern kingdom of Israel (different from that of the southern kingdom of Judah). Other discoveries have since been found at the site, pointing to early Israelite occupation.

One especially notable discovery in 2017 was that of a miniature faience figurine head of a royal individual. The head has a full beard, long hair and some sort of crown/band around his head. It is the first figurine of such exquisite detail and craftsmanship to have ever been discovered in Israel. If it does indeed represent a king, the question is, which one?

King Ahab is a contender. This (actual) son of Omri was one of the northern kingdom’s most prominent kings, mentioned on another of Assyrian King Shalmaneser iii’s inscriptions (the Kurkh Monolith). Ahab’s tumultuous 22-year reign spanned the early-mid ninth century (circa 873–852 b.c.e.).

An alternative Israelite king proposed is Jehu (circa 842–815 b.c.e.) or any of the minor kings in between. Other options, given the potential fluctuation of control of this northern border site, include Phoenician or Syrian (Aramean) rulers. In the words of Abel Beth Maacah codirector Nava Panitz-Cohen: “[I]f we surmise that the head depicts a dignitary, elite person or perhaps even royalty, we look at who were the historical figures at that time,” she said in an interview with Bible History Daily. “Candidates include Ahab and Jehu from the Israelite side, Hadadezer and Hazael from the Aramean side, and Ithobaal from the Phoenicians”—the latter, father of Ahab’s famous wife Jezebel (1 Kings 16:31). Either that, or it may just be a purely generic votive representation of an elite figure—an interpretation favored by codirector Naama Yahalom-Mack.

Bottom line is, we don’t know. Nevertheless, given the general time frame in question, it is interesting to speculate on which (if any) of the known ninth-century b.c.e. rulers this figurine may represent.

For more on this discovery, read “First Sculptured Head of Biblical-Period King Found in Israel.”

Hezekiah

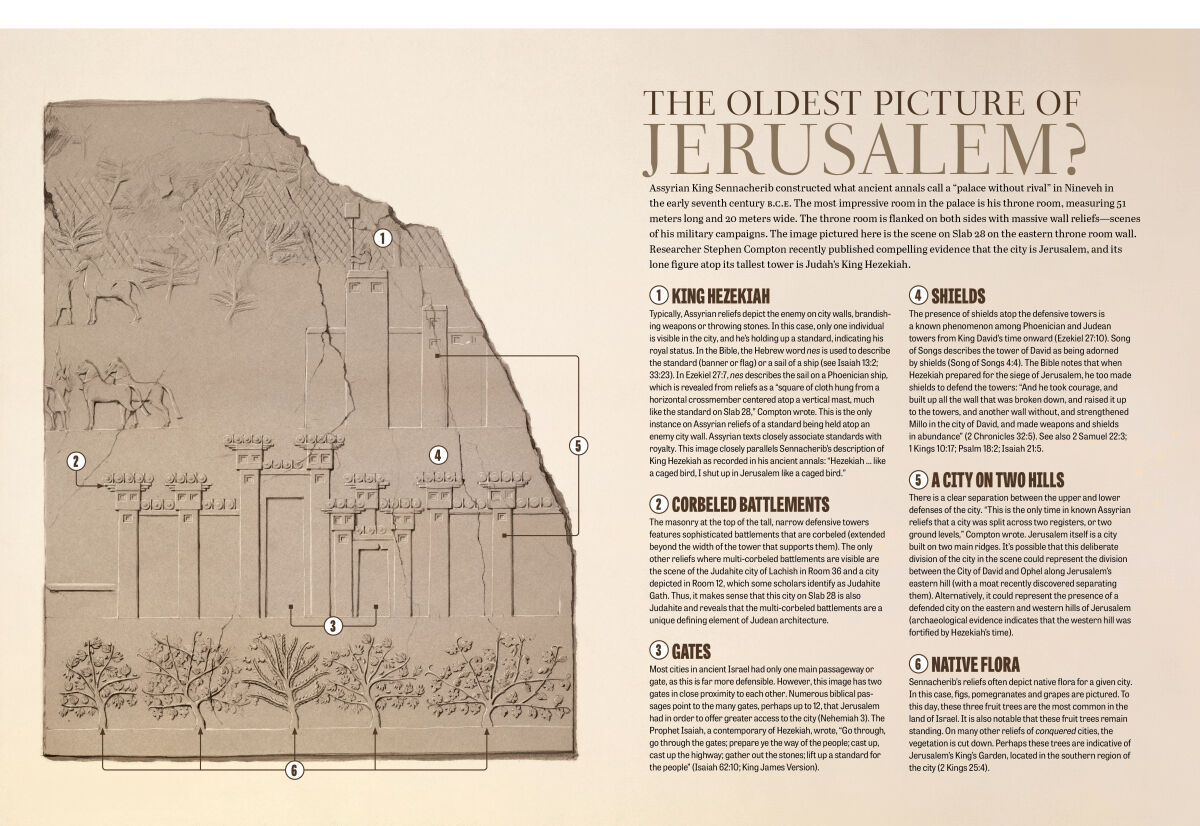

Finally in our list, we come to Hezekiah—and an artifact that served as the feature of our previous magazine, as well as No. 1 in our list of top 10 discoveries for 2025.

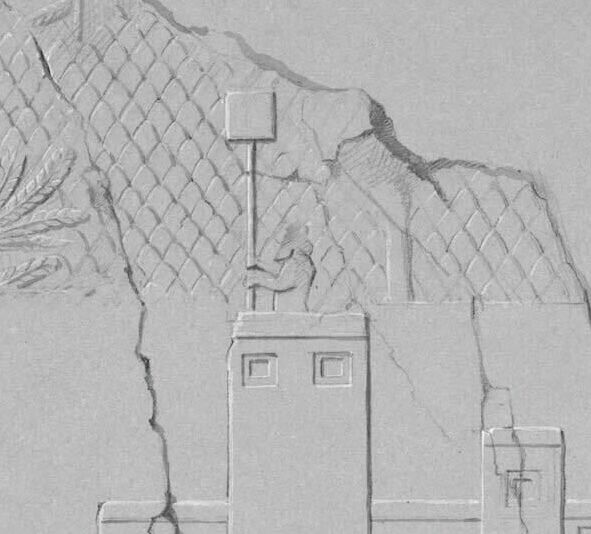

In short, Slab 28 of Sennacherib’s Nineveh palace contains a depiction of a particular and peculiar city, with a lone royal raising a banner atop the city walls. Based on the story flow of the reliefs in Sennacherib’s palace, paired with the account of his invasion into the Levant contained in his inscriptions, this city and its ruler had already been tentatively identified as Jerusalem and Hezekiah by Christoph Uehlinger in 2003. In 2025, Stephen Compton presented remarkable new research—from a new angle entirely—all but proving this city is indeed a representation of Jerusalem.

Logically, therefore, the royal figure contained within the city must be none other than King Hezekiah. The image of this lone figure atop a raised portion of the city, bearing a royal standard, is the veritable incarnation of Isaiah 30:17, prophesying at this time of an Assyrian onslaught until “ye be left as a beacon upon the top of a mountain, And as an ensign on a hill.” That and a visual representation of Sennacherib’s own braggadocious inscriptions, referring to “Hezekiah … shut up in Jerusalem like a caged bird.” In like manner, Slab 28 “appears to depict Hezekiah trapped inside Jerusalem” (Compton, “Sennacherib’s Throne-Room Reliefs: On Jerusalem and the Misplaced City of Ushu”).

Unfortunately, there is not much that can be gleaned from the depiction of the king himself—Hezekiah is portrayed at this scale in a rather generic Assyrian manner. Nevertheless, thanks to early work from the likes of Uehlinger and now the recent work of Compton, Hezekiah rightly takes his place on our list of illustrations of kings of Israel and Judah.

For more on this discovery, read “Revealed: A 2,700-Year-Old Depiction of Jerusalem and Hezekiah?”

Among Many

It bears emphasizing here that these images and illustrations we have briefly summarized in this article only pertain to the rulers of Israel and Judah. Many more biblical kings and officials from different nations and polities can be seen depicted on numerous other inscriptions, reliefs and stelae.

Included among these are pharaohs such as Shishak/Sheshonq i, So/Osorkon iv, Tirhakah/Taharqa, Necho/Neco ii and Hophra/Apries; kings such as Tiglath-Pileser iii, Shalmaneser v, Sargon ii, Sennacherib, Esarhaddon, Merodach-baladan ii, Nebuchadnezzar ii, Cyrus the Great, Darius i, Xerxes i, Artaxerxes i and Darius ii; and other figures besides. And these are just the more certain figures—not including numerous other more debated figures linked to the biblical account.

Thanks to more than a century and a half of biblical archaeology, these famous figures of the Bible can indeed not only be read about but seen.