Isaiah was a long-lived prophet in Judah who served through the reigns of four kings from David’s dynasty—the final being King Hezekiah. Chapters 36-39 of his book document the late eighth-century b.c.e. invasion of King Sennacherib of Assyria into the land of Judah.

Chapters 28-31 are delivered by Isaiah in the lead-up to the invasion—the period immediately following the fall of Samaria. These chapters have prophetic application to the coming of the Messiah, but they also have specific application for the time of Hezekiah, when Assyria would take almost all of Judah captive.

Chapter 30 begins as a warning to Judah, and perhaps to King Hezekiah himself, not to seek help in an alliance with Egypt against Sennacherib. Instead, Isaiah encourages Judah to rely on God for counsel and protection: “Woe to the rebellious children, saith the Lord, That take counsel, but not of Me; And that form projects, but not of My spirit, That they may add sin to sin; That walk to go down into Egypt, And have not asked at My mouth; To take refuge in the stronghold of Pharaoh, And to take shelter in the shadow of Egypt!” (verses 1-2).

Archaeological and historical evidence reveal that Hezekiah did choose to seek Egypt’s help before seeking counsel of Isaiah (see “Hezekiah’s Fatal Miscalculation? Evidence for ‘Trust in That Broken Reed, Egypt’”).

The result of this trust in Egypt instead of God was disastrous for Judah. Sennacherib’s ferocious army moved swiftly into Judah, taking over 46 fenced cities and sending hundreds of thousands of people into slavery. His incursion resulted in the near total destruction of the nation and the almost complete subjugation of the Jews.

Only Jerusalem was left to conquer.

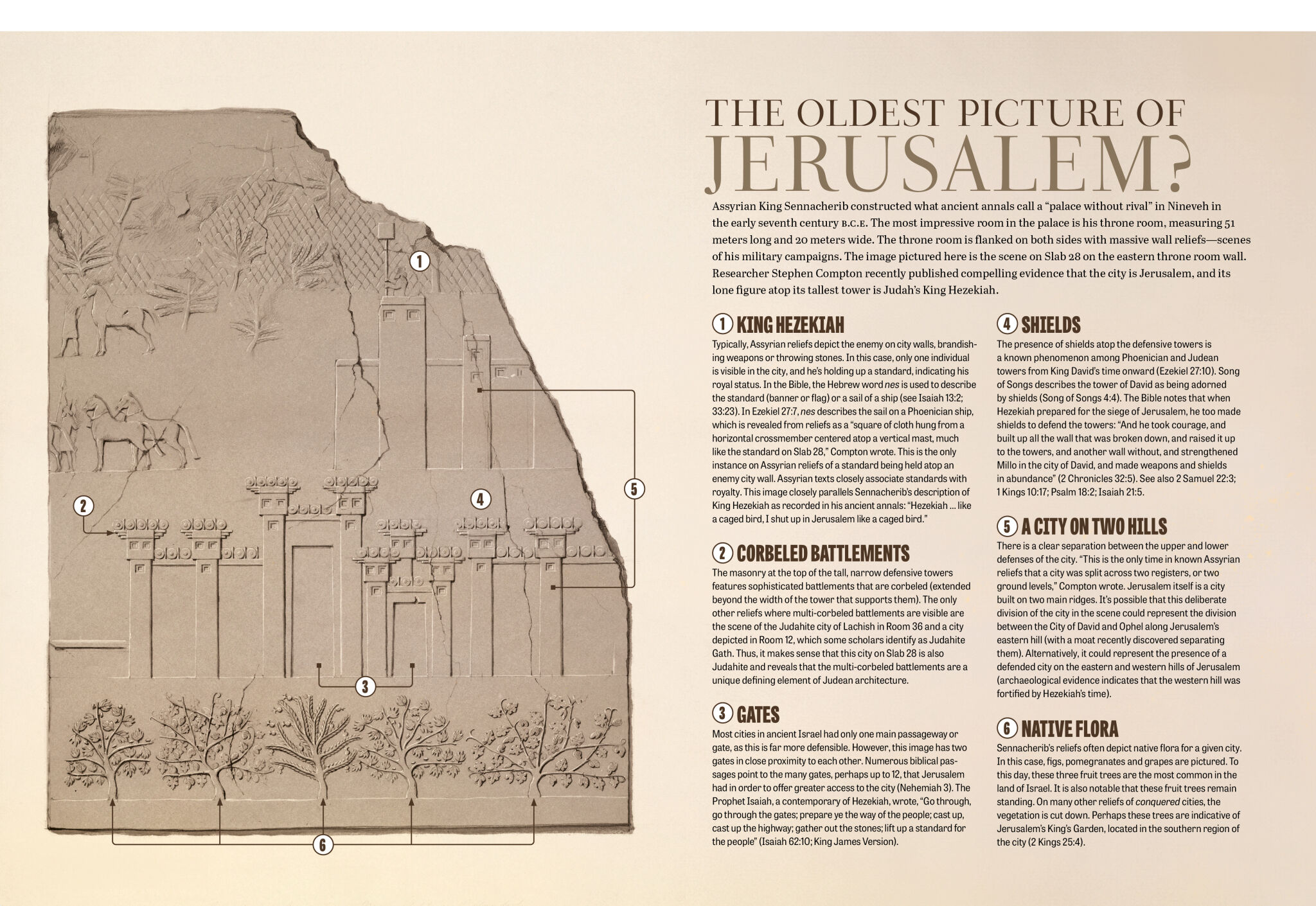

Isaiah then prophesies that the Assyrian onslaught would continue “Till you be left as a beacon upon the top of a mountain, And as an ensign on a hill.” The Hebrew word for “ensign,” nes, refers to the royal standard of Judah. After viewing the scene on Slab 28, one can’t help but connect the image of a lone royal figure standing on the highest tower of Jerusalem’s hill, bearing the nes of Judah, with this specific prophecy of Isaiah.

To this, we are compelled to ask a big question: Did Isaiah prophesy the exact scene that would play out in Jerusalem—one that Sennacherib would emblazon on the walls of his royal palace?

A few verses prior, Isaiah wrote, “Now go, write it before them on a tablet, And inscribe it in a book, That it may be for the time to come, For ever and ever” (verse 8). Here, in the same chapter, God tells the prophet to first inscribe these events on a tablet. This way the words can be a witness to the people of Isaiah’s day when the events would take place a few years later; thus confirming Isaiah’s place as a prophet of God and also the power of God to bring these events about. But the prophet was also to inscribe it in a book, so that it would be understood “for the time to come”; so that people far in the future would be able to read this same text.

Now, 2,700 years after the prophecy was given and the Jerusalem scene on Slab 28 identified, perhaps we can even envision the words of Isaiah in visual form.