Yad Vashem (יד ושם) is the name of Israel’s Holocaust memorial center, located on the western edge of Jerusalem. The name is derived from Isaiah 56:5, where the Hebrew phrase is rendered as “a place and a name” (King James Version).

I want to share here a story of a “place and a name”—or more specifically, one place, one name, but two individuals, 3,000 years apart—on Israel’s northernmost border.

Last July, I joined my colleague Brent Nagtegaal on his trip to Abel Beth Maacah to interview site director Prof. Naama Yahalom-Mack. Abel Beth Maacah is the closest archaeological site to Israel’s border with Lebanon; it is barely more than 500 meters from the “Blue Line.” We asked Naama if she and her team were nervous about excavating so close to the northern border, given the war situation. She explained that the excavation team had never felt safer. This is because the Hezbollah-occupied installations that once looked down on them had now been destroyed.

Just as it is today, Abel Beth Maacah was situated on the northern border in ancient biblical Israel. One of the key artifacts to come from the site made headlines in 2020: the discovery of a vessel sherd dating to the 10th to ninth century b.c.e. that bore the inscription, “Belonging to Benayau” (לבניו) in the early Hebrew-Phoenician script.

The name was evidently Israelite, a fact clearly demonstrated by the “Yahwist” theophoric ending. Further, it was spelled in a manner particular to the northern kingdom of Israel (it ends with יו/yau; rather than the more typical Judahite spelling יהו/yahu or יה/ya—a convention that continues to this day). This personal name is found multiple times throughout the Bible and is typically transliterated as Benaiah. A common English spelling used by modern individuals with this name is Benaya.

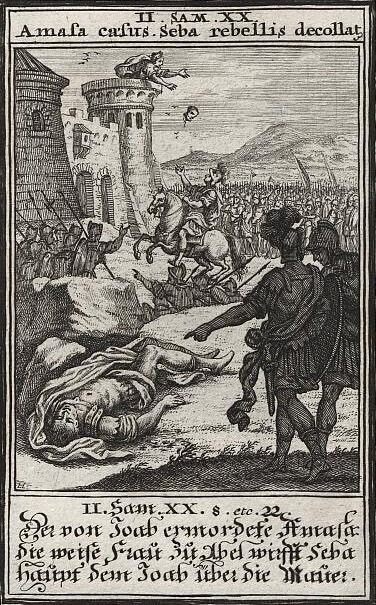

The find was extraordinary and helped identify the site as an Iron Age iia Israelite settlement from nearly 3,000 years ago. This was a reality already attested to in the biblical account. During the reign of David, for example, “Abel of Beth-maachah” is described as a “city … in Israel” (2 Samuel 20:15, 19). Yet surely the border of ancient Israel couldn’t have extended this far north—so reasoned minimalist-leaning scholars. The Benayau Inscription demonstrated otherwise.

After visiting the site, Brent and I drove up from the Hula Valley (Tel Abel Beth Maacah is located within its northern mouth) and ascended Naftali Ridge, a hill 3 kilometers west, to get some shots overlooking the tel. While Abel Beth Maacah is adjacent to the Lebanon border to the east, Naftali Ridge borders Lebanon to the west (with the western side of the hill comprising the Lebanese town of Al-Aadaissah and the eastern side Israel’s kibbutz Misgav Am). Just before the border, on the Israeli side, is a lookout where we stopped to take pictures of Abel Beth Maacah directly below us.

I was stunned to see the name of the lookout: Mitzpe Benaya (Benaya Lookout).

Within the wooden structure, a small group of Israelis were commemorating the memory of a fallen soldier: Maj. Benaya Rhein.

An audio guide at the lookout told the story. On July 12, 2006, two Israeli military vehicles were ambushed by Hezbollah militants in a cross-border raid into Israel. Three Israeli soldiers were killed and two more kidnapped. A failed rescue attempt resulted in the deaths of five more Israeli servicemen. When Israel refused to bow to Hezbollah’s demands for a prisoner exchange, the Second Lebanon War unfurled, within which Benaya served—and was killed.

Maj. Gen. (Res.) Tamir Hayman recounted Benaya’s involvement in the war: “The late Benaya Rhein was killed in the Second Lebanon War in a tank with a crew that reflects both Israeli-ness and the idf as the people’s army.” The 27-year-old Benaya “was supposed to be on leave between assignments but couldn’t stay home.

He went up north and did not stop pressuring his commanders until they gave him a tank and a special crew. And this tank crew, without receiving an order, decided to do what was necessary. If food needed to be brought, they would bring combat rations to the fighters at the front. If maps were needed—no problem. Need to rescue the injured? They will go anywhere. Soon the rumor about the “Benaya Force,” the tank crew that comes to help, spread among the reservists who fought on the eastern front in Lebanon ….

Benaya, a religious soldier from the settlement of Karnei Shomron, commanded a crew whose special composition almost seems to have been put together by a playwright who wanted to illustrate why the idf is still the people’s army. Benaya’s tank crew included Sgt. Alex Bonimovich, an immigrant from Russia; Sgt. Adam Goren, a secular kibbutznik; and Sgt. Uri Grossman, a sabra from Jerusalem, son of the acclaimed and sharply critical leftist writer David Grossman.

The men left on a final mission on Aug. 12, 2006—just two days before the end of the conflict—when their tank was hit by a projectile, killing the crew. “I, on Memorial Day, will commemorate my friends and the soldiers under my command who did not return,” concluded Hayman in his April 24, 2023, post (“Benaya’s ‘Israeli Tank’”), professing his love for “Benaya, my soldier” and wondering about the symbolism of his life.

I wondered about it too, visiting the Benaya Lookout. Here we were, familiar with the field of archaeology and the connection of this northern location to the name Benaya—interacting with a small Israeli group who knew nothing of the archaeology, yet who also connected this very same northern location with the name Benaya. They were stunned to hear about the connection with the site below us, Abel Beth Maacah.

This is one of the incredible and powerful realities of archaeology. Biblical archaeology can bridge a 3,000-year gap—and show us that in many ways, not much has changed for this name and this place.

Today Maj. Benaya Rhein is memorialized on a website (benaya.name), which contains an account of his life, personal letters, details about his family, and the lookout dedicated in his name soon after his death, near where he left on his final mission. One particularly memorable diary entry was written during his trip to Poland in 2000, where he visited the Treblinka concentration camp—a place in which the “stones spoke” to him. “When I traveled to Poland, I felt death. On the plane, there were Poles who were happy as they approached their country. When we landed, they applauded; they had arrived home.

I also arrived home, to the cemetery of the Jewish people. To the cemetery of my grandfather’s family, to the cemetery of my grandmother’s family. Throughout my stay in Poland, death walks with me—Warsaw is a beautiful city, but for me it is dead. In Tykocin, in Treblinka, I feel that I am stepping on the dead, that I am stepping on fellow human beings. Death is everywhere. But I know that this death gave birth to life and this life is me, you, they, we. This life gave me the right to be a free Jew in the Land of Israel. This life gave me the right to be a soldier in the Land of Israel. This life gave me the right to represent, as a Jewish soldier from the Land of Israel, all those who were and are not and those who are. This life demands and demands, what exactly is difficult for me to define and about which I am still pondering.

But it is clear to me that the demands are great and binding, and may I, Benaya, have the strength to meet them.

He did, and he too shares a name and a place, both figuratively and literally—one that is 3,000 years old.

And from death, new life emerges. For the same evening Benaya’s family was informed of his death, his sister went into labor—and a son was born.

Named Benaya.