The biblical King Manasseh of Judah is a fascinating, multifaceted monarch. The Bible describes him as infamously evil, practicing witchcraft and going so far as to sacrifice his own children to pagan gods (2 Chronicles 33:6). Jewish tradition holds that he even had the Prophet Isaiah sawn in two (also potentially referenced in the New Testament; Hebrews 11:32, 37). Yet Manasseh is also famous for his repentance, turning back to God and restoring His worship (2 Chronicles 33:12-19).

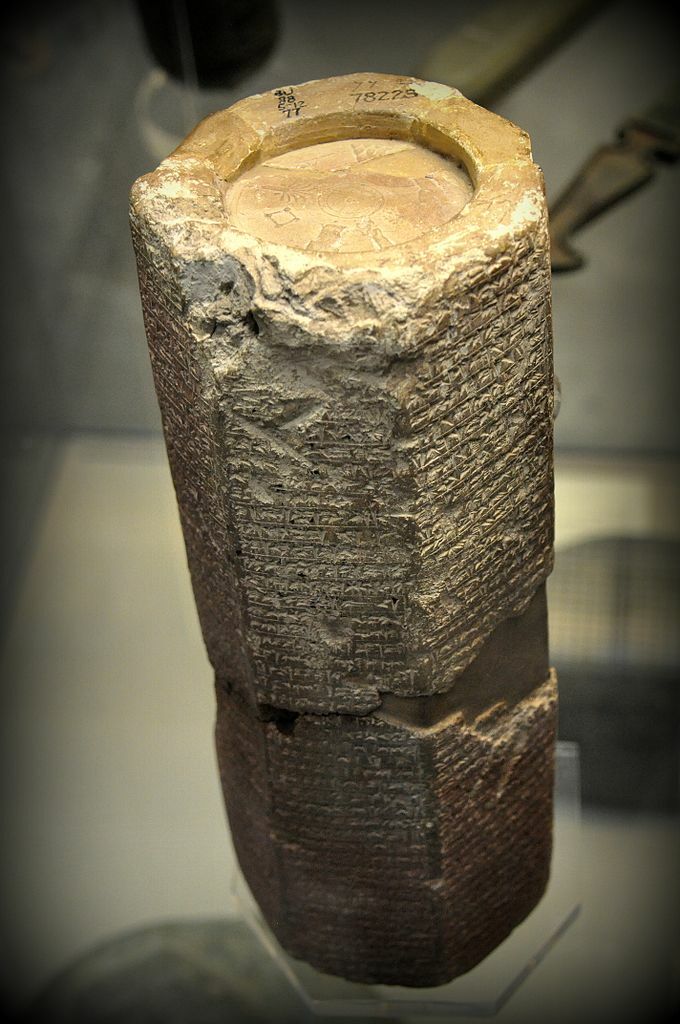

The king’s existence has been confirmed by archaeology. He is mentioned in the seventh-century b.c.e. Assyrian inscriptions of kings Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal as being under tribute to them, which fits well with the biblical account of Manasseh’s capture, deportation and eventual release back to Jerusalem (following his repentance), certainly under some kind of tributary agreement.

But a single Bible verse relating to this brief Assyrian captivity of Manasseh—punishment from God for his sins—is mysterious. The King James Version reads as follows: “Wherefore the Lord brought upon them the captains of the host of the king of Assyria [at this point in history, King Esarhaddon], which took Manasseh among the thorns, and bound him with fetters, and carried him to Babylon” (2 Chronicles 33:11).

What exactly does among the thorns mean?

Fishing With Thorns?

The Hebrew word translated thorns is indeed used to refer to thorny plants (i.e. 2 Kings 14:9 and Song of Songs 2:2—possibly the origin of our saying, “a rose among the thorns”). But the context in 2 Chronicles 33 points to something else entirely.

The root of this Hebrew word חוח means to pierce, and the word is often translated as “hook” as well as “thorn.” A good sense of this meaning can be found in the book of Job, describing the mighty sea creature Leviathan: “Can you put a reed through his nose, Or pierce his jaw with a hook?” (Job 41:2; New King James version).

Here, the use is singular. In 2 Chronicles 33, the use is plural—King Manasseh was taken by the Assyrians with hooks. The Jewish Publication Society therefore translates the passage: “the king of Assyria … took Manasseh with hooks, and bound him with fetters.” Apparently these “fetters” refer to some sort of leg irons (albeit made of bronze or copper, designed to allow shuffling along but to inhibit fleeing). Being made to march in such “leg irons” would be bad enough—but imagine being led along by hooks!

So 2 Chronicles 33 informs us that Manasseh, upon being bundled out of the city by the Assyrians (who must have been threatening to tear it down unless the king was turned over), was pierced through with hooks and led away captive. The verse doesn’t tell us where those hooks were placed. However, we can get a good sense from another proximate event involving Assyria, immediately before the reign of King Manasseh.

2 Kings 19 describes the failed campaign of Assyrian King Sennacherib against Jerusalem at the end of the eighth century b.c.e., at the time ruled by Manasseh’s father, Hezekiah. (Evidence for Sennacherib’s campaign into Judah at this time is legion, and Hezekiah’s reign is one of the most well attested to in archaeology.) In this chapter, after Hezekiah turned to God, the Prophet Isaiah tells him that Sennacherib, though having conquered the rest of Judah, would be defeated at Jerusalem by a great miracle and would return humiliated to Assyria. (And to this day, debate rages as to why, based solely on the clear archaeological evidence, Sennacherib did not capture Jerusalem!)

Here was God’s message to Sennacherib: “Because of thy raging against Me, And for that they tumult is come up into Mine ears, Therefore will I put My hook in thy nose, And My bridle in thy lips, And I will turn thee back by the way By which thou camest” (2 Kings 19:28). This was God’s message to the Assyrian king, in such language he would clearly understand—based on what was evidently Assyrian practice at the time. God would metaphorically put His hook in Sennacherib’s nose and lead him to Assyria!

Fast-forward three or four decades, and due to paganism and rebellion, we have a completely reversed situation: The son of Sennacherib, Esarhaddon, leading away the son of Hezekiah, Manasseh, in the same manner to Assyria, with hooks. As such, based on the above, many other translations render 2 Chronicles 33:11 similar to the following (from the New English Translation): “So the Lord brought against them the commanders of the army of the king of Assyria. They seized Manasseh, put hooks in his nose, bound him with bronze chains, and carried him away to Babylon.”

Thus far, we have examined this scripture from a purely biblical perspective. But archaeological discovery likewise attests to this as an established Assyrian practice.

Those Assyrians …

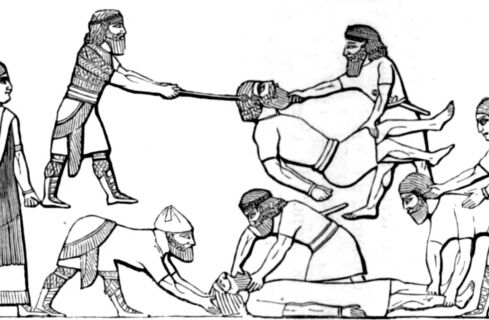

The Cambridge Bible Commentary summarizes: “Assyrian kings sometimes thrust a hook into the nostrils of their captives and so led them about. The practice is illustrated on many Assyrian reliefs in the British Museum.”

One such poignant example from archaeology is a victory stele belonging to King Esarhaddon himself (circa 670 b.c.e.), depicting the king in large relief form standing over two conquered kings, held captive by him with a rope that is hooked—in this case—through the victims’ lips. (The stele is on display in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin, Germany.)

Another wall relief from King Sargon ii’s palace at Khorsabad (Sargon was the father of Sennacherib) is preserved in drawings of the relief which, based on the interpretation, shows three prisoners hooked through either the nose or mouth. In especially brutal fashion, the Assyrian king in this relief uses the ropes to hold the prisoners in place, while putting their eyes out with a spear. Another Assyrian relief again shows hooks through the ears of a victim (see the reproduction drawing below).

These artifacts give us an image of how Manasseh must have been led along, unaware of his eventual fate, either by hooks through the nose, through the mouth—or both. Again, 2 Chronicles 33:11 simply relates “hooks” without directly specifying a certain part of the body (and 2 Kings 19:28 does mention being led by the “lips,” as well as a “hook in the nose.”)

This all dramatically highlights (and this is the least of it) the brutality of the Assyrians, something attested to throughout the Bible—and an interesting link to the book of Jonah. (For more information about this, read our article “Jonah’s Remarkably Accurate Account of Assyria.”)

Leonard Cottrell wrote in Anvil of Civilization (1957, emphasis added): “In all the annals of human conquest, it is difficult to find any people more dedicated to bloodshed and slaughter than the Assyrians. Their ferocity and cruelty have few parallels save in modern times”—a clear reference to events of the prior decade, as perpetuated by Nazi Germany. (As an aside, the fourth-century c.e. historian Jerome directly named the Assyrians as being among Indo-Germanic tribes.)

One final, archaeological point. Could the individual portrayed on the Esarhaddon Stele be the very King Manasseh himself? The kneeling figure in the middle (see the close-up below) has been identified as either the Cushite Egyptian prince Ushankhuru or Pharaoh Taharqa (likewise mentioned in the Bible around this time period). But the figure on the right has not been as positively identified, and the text on the stele gives no confirmation. One suggested option is the Tyrian king Baal i. Whoever he is, he is certainly attired in “Asiatic” style (an umbrella term that includes the Israelites), and his appearance closely matches that of the Israelite King Jehu as depicted on the Assyrian Black Obelisk. His beard and hair also match that of a royal statuette found at a First Temple period site in the north of Israel, Abel Beth Maacah.

Could this, then, be Manasseh? After all, the stele commemorates a successful Assyrian campaign that would have taken them through the Levant and into Egypt. It dates to the right period in this biblical figure’s life (a campaign that took place around 671 b.c.e., roughly the halfway point in Manasseh’s long reign). We already have the biblical account of a Levantine king being led away by hooks at this time. Here we find a picture of one. We even see that the captive kings have been clapped in “fetters,” as mentioned in the Bible (although the standing king’s garment is obscuring his). Is it a stretch to connect the dots?

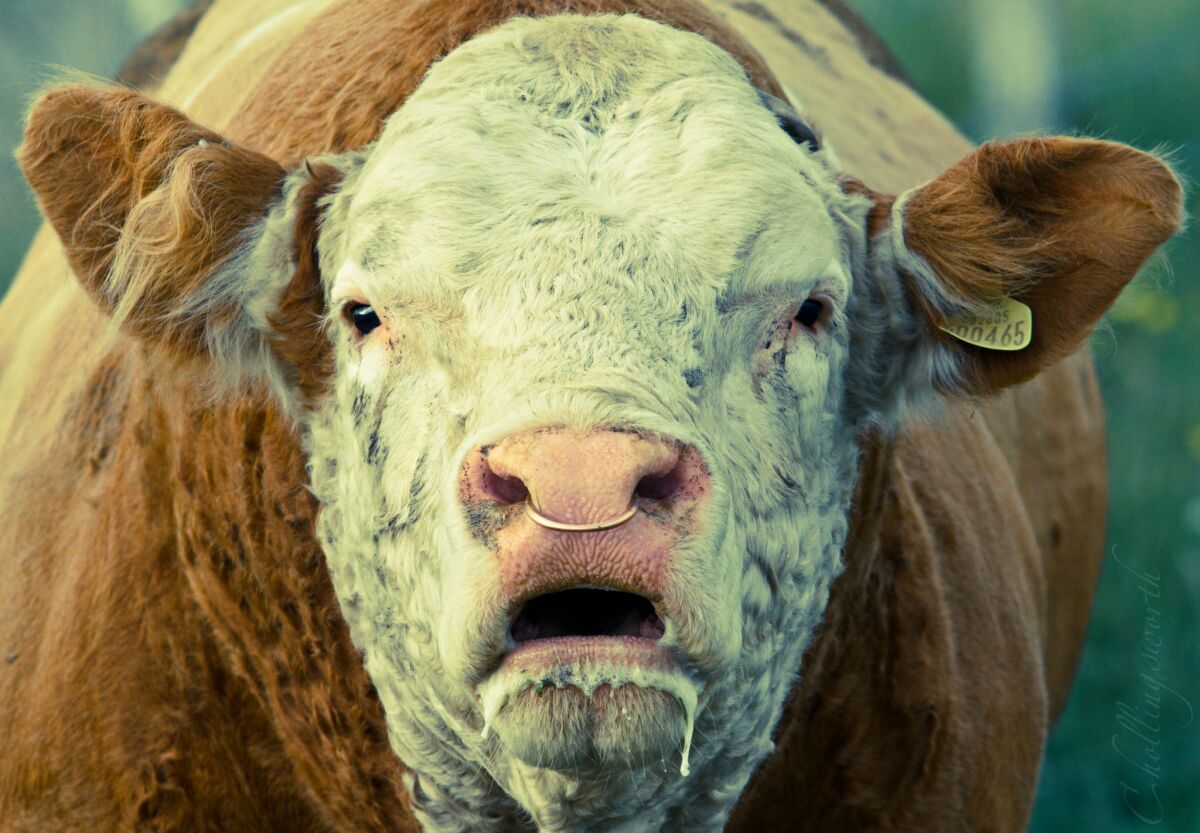

Finally, there is an interesting moral behind the king of Judah being led away by “hooks”—in fact, behind the eighth-century b.c.e. Amos’s wider prophecy about the same. “[L]o, the days shall come upon you, that he will take you away with hooks, and your posterity with fishhooks” (Amos 4:2; kjv). Rebellious Israel is sometimes referred to in the Bible with cattle symbolism: “For Israel is as obstinate as a stubborn cow. Can the Lord now shepherd them like a lamb in an open meadow?” (Hosea 4:16; csb). Stubborn bovines are, of course, themselves brought to bear by a similar hook, or ring, through the nose.

So perhaps it should be no surprise that the man regarded as the most evil of the kings of Judah was himself eventually brought to bear, quite literally, in such a manner. The Bible describes God Himself at times using the brutality of the Assyrians to effect His purposes in correcting rebellion: “O Assyrian, the rod of mine anger, and the staff in their hand is mine indignation” (Isaiah 10:5, kjv).

As such, in a way, 2 Chronicles 33:11 is a lesson in how the smallest of objects can bring to bear the largest, most evil or most obstinate and stubborn of creatures.