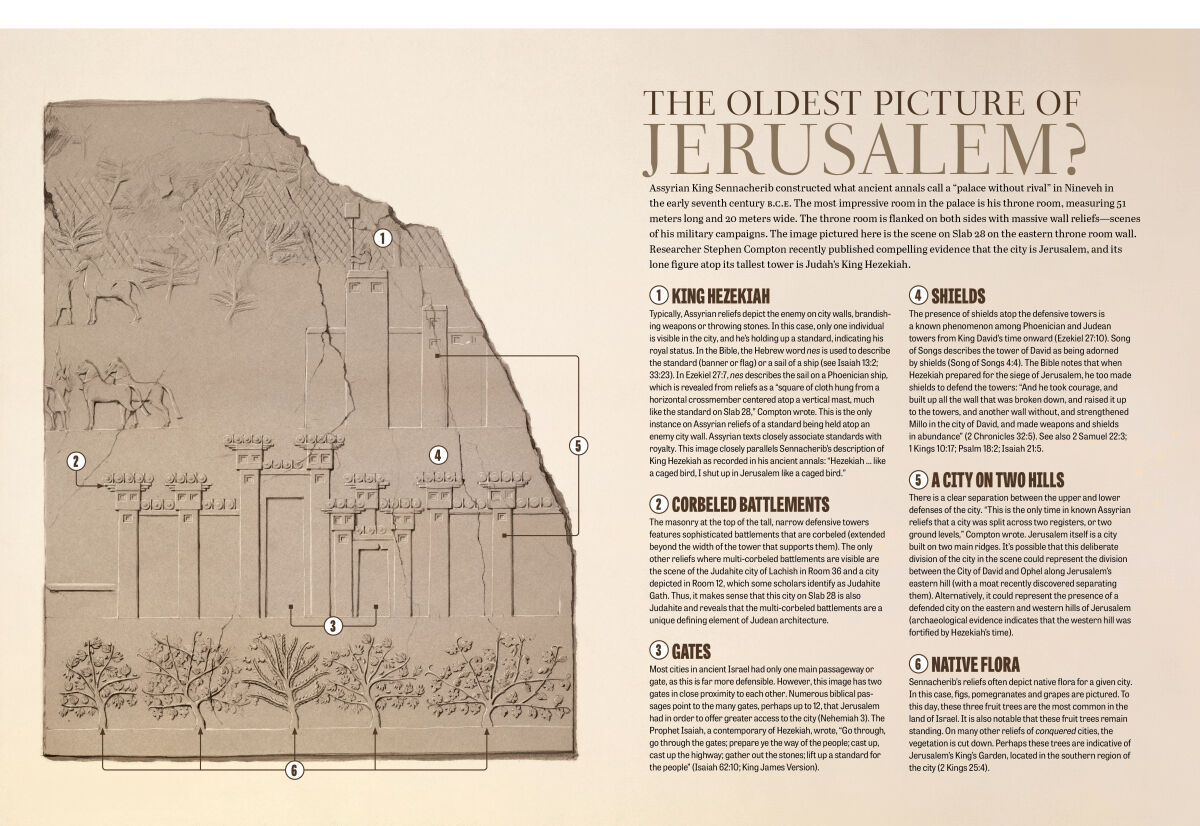

When researcher Stephen Compton shared with me an image of Slab 28 of Sennacherib’s throne room in Nineveh, I was awestruck. Surveying the scene on the relief, the identity of the city portrayed grew increasingly obvious: This was Jerusalem!

We were in Boston attending the 2024 American Schools of Overseas Research (asor) conference, where Compton was presenting his interpretation of Slab 28. Listening to him lay out his research, and discussing all the archaeological and historical connections, it was clear he was onto something. He might be right! I thought. This is the oldest work of art depicting Jerusalem ever found!

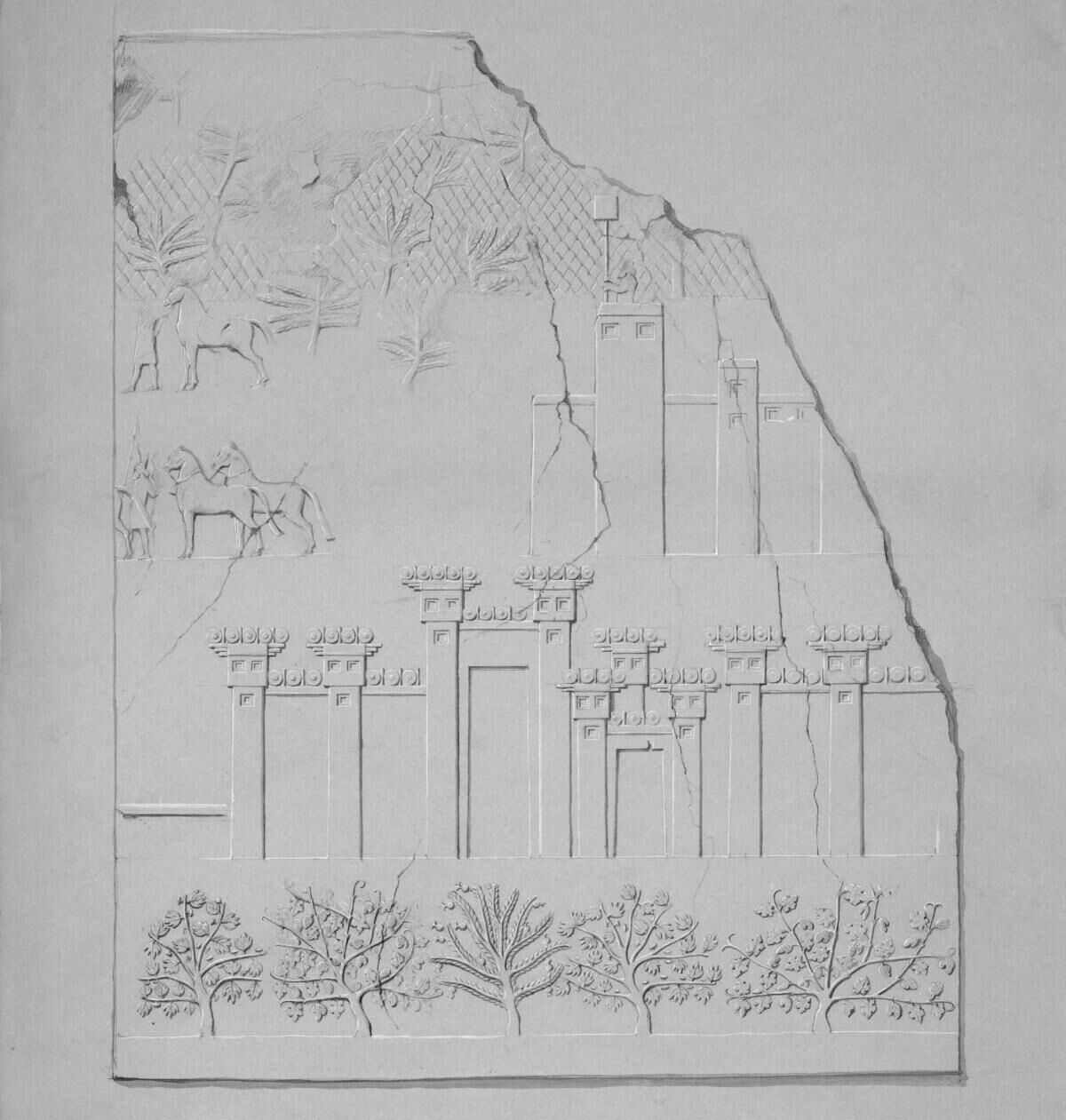

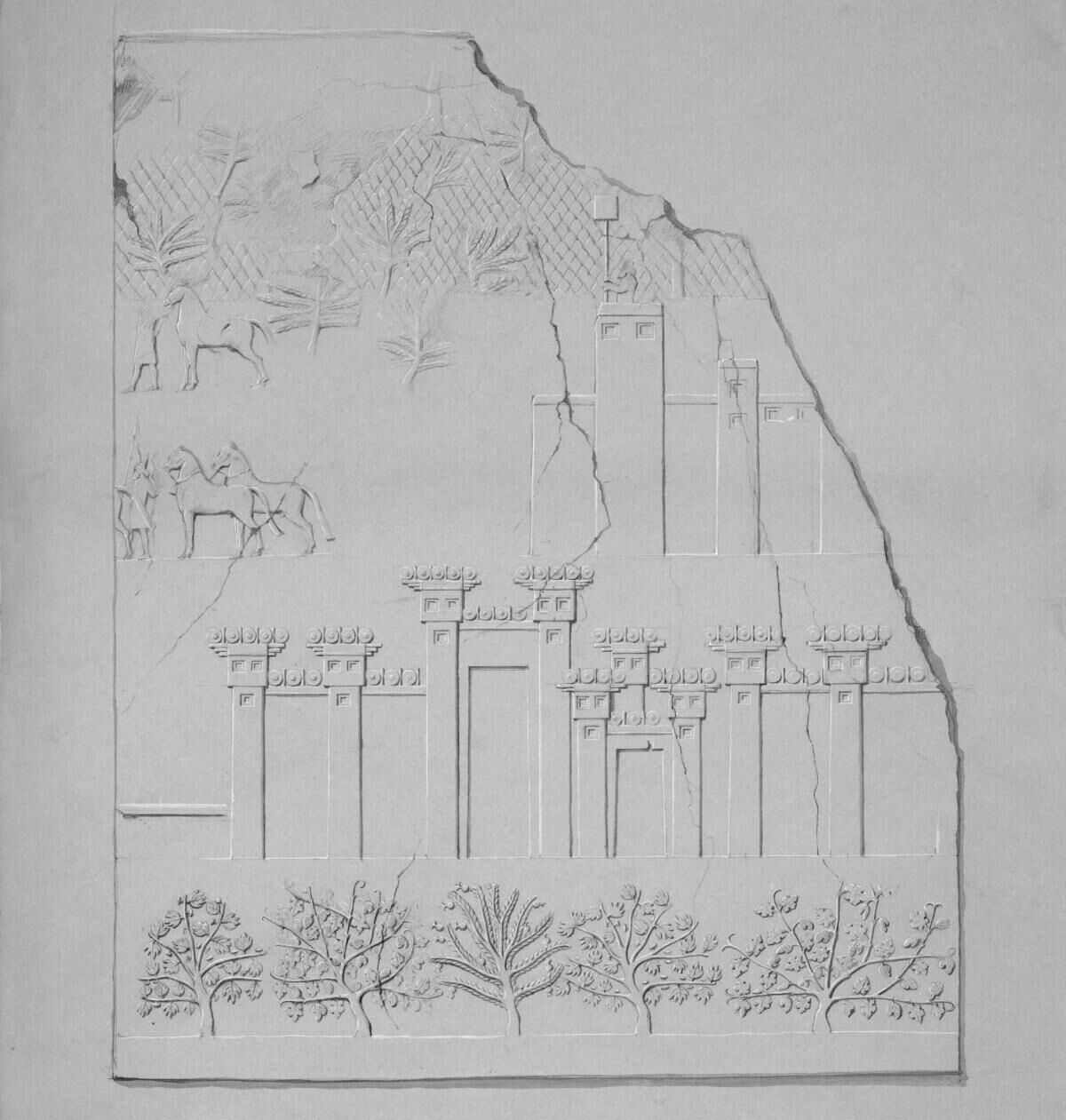

The evidence began to accrue immediately. There were the three species of fruit trees—grapes, figs and pomegranates—all native to Israel and Judah. It was noteworthy too that, unlike some depictions of trees on other reliefs, these were not hewn down, suggesting this city remained unconquered. Above the fruit trees, there was a massive city wall, defensive towers and two gates. Depicted on the defensive towers were twice-corbeled battlements. Although I didn’t know it at the time, these were almost identical to those on the Lachish wall reliefs, suggesting this was a Judean city. On top of the corbeled battlements was a series of shields, recalling scenes described in several biblical passages from the time of King David onward.

Higher up the slab, there was a second series of walls and towers. This was interesting. Did this indicate this city occupied two hills or ridges, just like Jerusalem?

Finally, standing alone in the tallest tower was a single figure. He’s the only individual in the entire city. And he’s holding a standard, suggesting royal status. If Slab 28 depicts a scene from King Sennacherib’s invasion of Judah, and if the city depicted was Jerusalem, then this lone royal figure had to be King Hezekiah!

Is this really a 2,700-year-old representation of biblical King Hezekiah? Was this whole scene the earliest graphic representation of Jerusalem ever discovered?

I left asor eager to read Compton’s paper, where all his research would be presented for study and consideration by scholars and scientists around the world. More than a year later, after studying his detailed and thorough analysis, I am convinced: Slab 28 portrays Jerusalem!

The article, titled “Sennacherib’s Throne-Room Reliefs: On Jerusalem and the Misplaced City of Ushu,” was published in the October 2025 issue of the Journal of Near Eastern Studies, a prestigious journal published by the University of Chicago.

In this article, we will review Compton’s spellbinding discovery—representing not just the earliest portrayal of Jerusalem ever found but the depiction of one of biblical Judah’s greatest kings.

The Throne Room

The Neo-Assyrian Empire was a wealthy, highly militarized Mesopotamian superpower that dominated the Near East for roughly 300 years between 911 and 612 b.c.e. Assyria’s formidable army invaded Israel and Judah in the late eighth century, starting in 745 b.c.e. and ending with King Sennacherib’s failed campaign to destroy Jerusalem near the end of the eighth century b.c.e.

This history is well documented, both archaeologically and in ancient texts, including the Bible. Even before this discovery, perhaps no event in biblical history was more corroborated than Assyrian King Sennacherib’s military campaign into Judah.

There are archaeological remains from the late eighth century b.c.e. of the massive destruction layers at Judean sites like Lachish and Azekah. There is evidence of the siege preparations in Jerusalem enacted by King Hezekiah of Judah, most notably, a 550-meter (1,800 feet) water tunnel running underneath the city, which is still accessible today and mentioned in three places in the Bible. There is the seal impression, a royal signature, of King Hezekiah of Judah, discovered in the royal quarter of Jerusalem in 2009 and on display at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem.

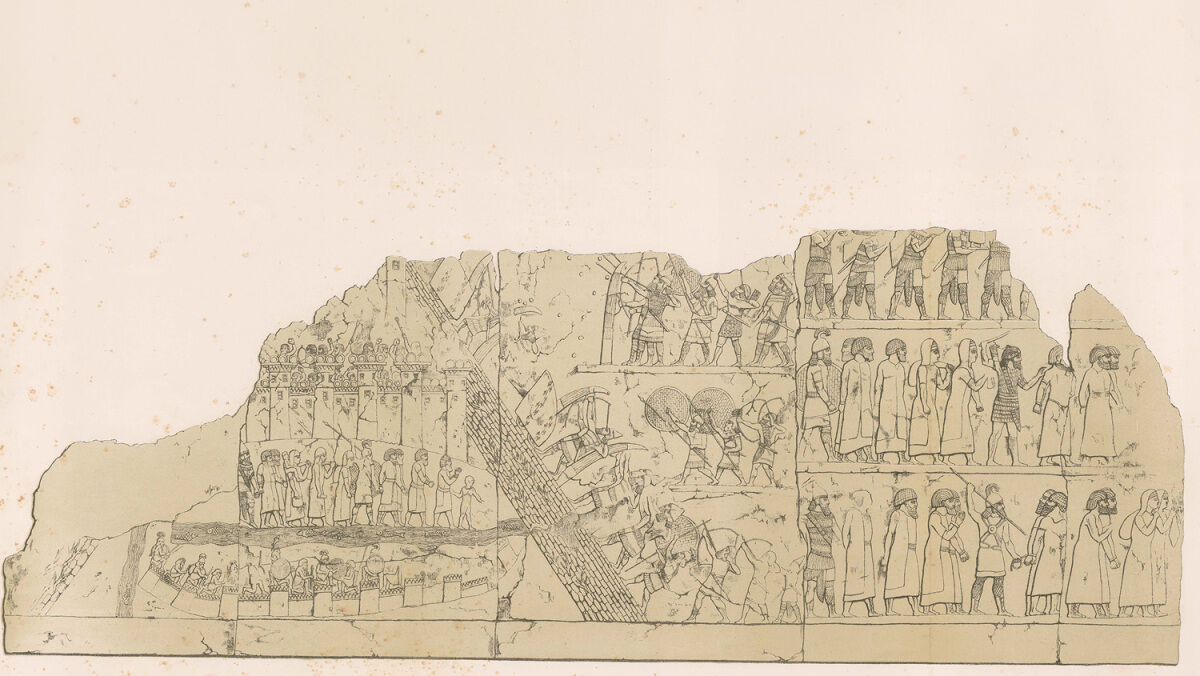

Then there are the prized Lachish wall reliefs, lifted from ancient Nineveh and housed in the British Museum in London, pictorially documenting the siege, capture and destruction of Judah’s second-most important city.

Finally, there are the written annals of King Sennacherib’s exploits that each bear record of Judah’s King Hezekiah being trapped in his royal city Jerusalem “like a bird in a cage” (see “Sennacherib’s 17 Hezekiah Inscriptions”).

This “new” piece of evidence takes us to the capital of the ancient Assyrian Empire itself.

Archaeological excavations at ancient Nineveh, the capital of the Neo-Assyrian Empire during the time of Sennacherib, first began in the 1840s with British archaeologist Sir Austen Henry Layard on behalf of the British Museum. His large-scale digs and those of subsequent British archaeologists uncovered massive palatial structures on Kuyunjik, one of two tells at the city.

Following the death of his father, Sargon ii, Sennacherib developed the site in 703–692 b.c.e. for his royal citadel and constructed in the southwest of the tell what he called a “palace without rival.” Sennacherib’s palace compound is immense; it takes up just over 30 acres, or around 23 football fields.

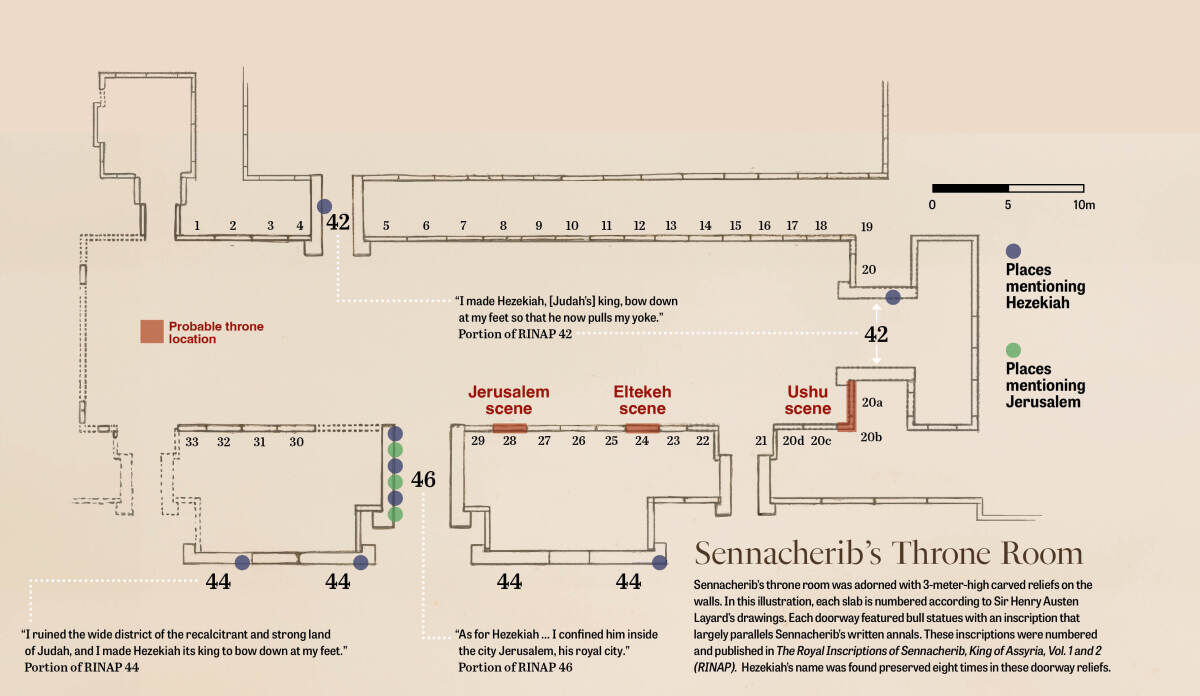

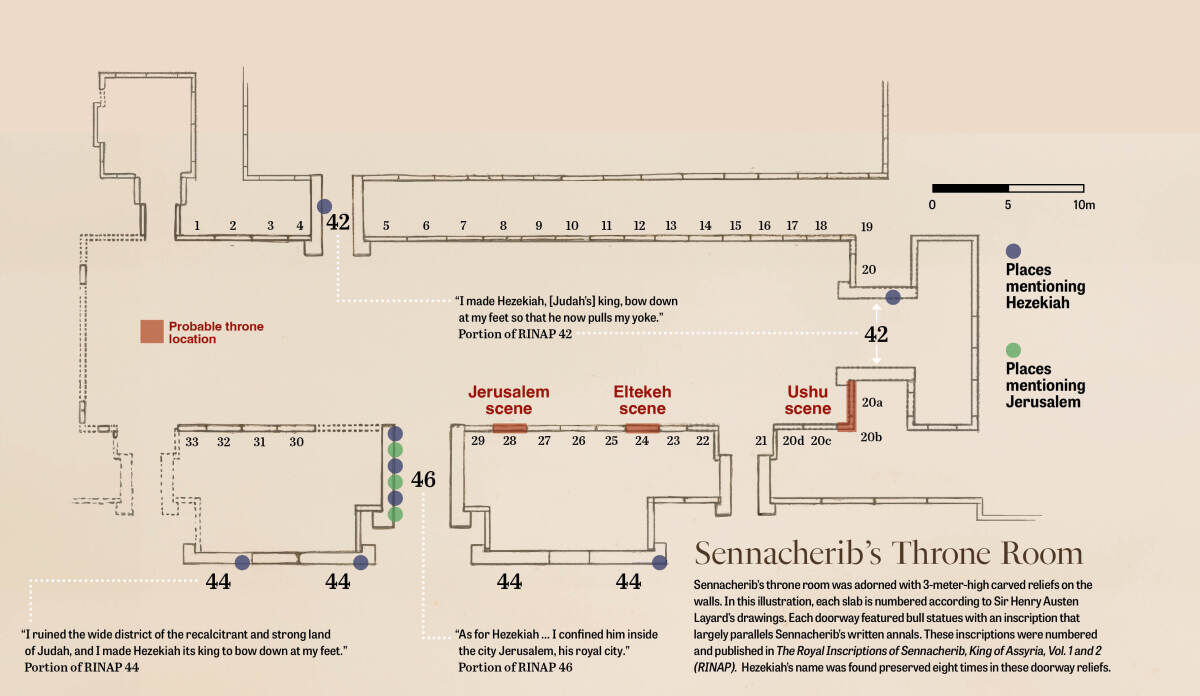

The rooms and hallways of King Sennacherib’s palace are adorned with wall reliefs, carvings that document the exploits of the ancient Assyrian king. The individual reliefs are gigantic, rising almost 3 meters above the ground on many of the walls. All totaled, Layard uncovered just over 70 rooms in the palace, many of them adorned by roughly 3 kilometers (nearly 2 miles) of wall carvings.

Room 36 (by Layard’s numbering) contains one of the most famous scenes. The reliefs in this room depict the account of Sennacherib’s devastating destruction of the Judahite city of Lachish. This scene is on display at the British Museum in London. As incredible as the relief is, Room 36 is actually pretty ordinary (only 12 meters long, or 39 feet), and the scene does not occupy a position of prominence within the palace.

The most impressive room in the palace is Sennacherib’s throne room. This room is 51 meters long and 20 meters wide (167 feet by 66 feet). The walls were originally lined with around 35 carved stone panels, with scenes unfolding across multiple panels to tell narratives. The throne room is “the largest room ever found in ancient Assyria,” Compton explained in an interview in November. When it comes to the wall carvings, it is “prime real estate in the palace.”

Slab 28 is in the throne room, the epicenter of Sennacherib’s prestige.

Unfortunately, Sennacherib’s throne room, along with its over 100 meters (330 feet) of reliefs, was destroyed in 2015–2016 by the Islamic State. The obliteration of archaeological sites across Syria and Iraq is one of the great intellectual tragedies of our time. Since 2021, the University of Heidelberg has led a valiant effort to salvage and restore whatever is left of Sennacherib’s palace. Sadly, only the lowest stubs of the wall foundations remain of the throne room.

Fortunately, Layard and his team documented Sennacherib’s throne room (and much of Nineveh) in detailed reports, including several drawings and illustrations. Without the actual reliefs to study, Compton relied on these detailed drawings and descriptions.

It is important to note: Compton isn’t the first to propose that a Jerusalem scene was captured on the inside of Sennacherib’s throne room. Assyriologist Christoph Uehlinger suggested some 20 years ago that the section of wall in question (Slab 28) could be a scene of Jerusalem. Uehlinger, whom Compton credits for his foundational insights, had been on a quest to find Jerusalem on a wall somewhere on the 3 kilometers (2 miles) of reliefs. In the end, he settled that Jerusalem might be depicted in three different scenes (Slab 28 being one of them). After presenting the research, Uehlinger concluded in 2003 that “present pictorial evidence can neither prove nor exclude the possibility that the siege of Jerusalem was depicted on one of Sennacherib’s palace reliefs” (“Clio in a World of Pictures”).

Unlike Uehlinger, Compton wasn’t on a quest to find Jerusalem. He was searching for the city of Ushu, a dominant Phoenician city mentioned as being conquered in Sennacherib’s annals and yet never found in the palace wall reliefs. “I worked on the wall because Ushu was the main mystery that hadn’t been solved from a Neo-Assyrian perspective,” Compton recalled in our interview. “I’m a history nerd, and this is my particular field.”

In order to provide stronger evidence for Jerusalem on Slab 28, it is important to solve the mystery of Ushu.

The Mystery of Ushu and Eltekeh

It is generally accepted that the reliefs covering the throne room’s eastern wall document major battles in Sennacherib’s third military campaign. Based on his own annals, such as the Oriental Prism (now at the University of Chicago), this campaign impacted three nations of “Hatti Land,” or the eastern Mediterranean. These were Phoenicia, Philistia and Judah. Unfortunately, not all the wall reliefs in the throne room were drawn by Layard. Others were too degraded to draw, or perhaps even left blank in antiquity. So we don’t have illustrations of every relief.

Nevertheless, three segments of the engravings were drawn well enough for scholars to debate what exactly is depicted on each one.

In his report, Compton took the description of Sennacherib’s third campaign as it was recorded in Sennacherib’s annals and considered it alongside the geographic and architectural markers on the reliefs and documented by Layard. He also considered all this evidence in the context of regional geography. Putting all these pieces of information together, Compton concluded that the scenes on the eastern wall of the throne room are recorded in chronological order.

According to the annals, Sennacherib conquered the Levant by moving from north to south. First, he destroyed eight strong-walled cities of Phoenicia, then conquered the cities of the Philistines, including engaging in a major open-field battle near Eltekeh against the Egyptian-Cushite army. Finally, the annals record Sennacherib’s subjugation of 46 strong-walled unnamed cities of Judah under the leadership of “Hezekiah of the land of Judah.”

The first scene on the reliefs (panels 20a and 20b), according to Compton and others, portrays Phoenician ships fleeing from a coastal city. But no inscription on the relief identifies the city.

According to the textual evidence, during the third campaign, Phoenician King Luli escaped by ship. Most scholars agree this is the scene depicted on panels 20a and 20b. But what city is this exactly? Prior theories posit that it was Phoenicia’s Tyre, or perhaps even the southern city of Jaffa. Compton disagrees and made a compelling case that this is Ushu, a city which, until his paper, had never been located on the Phoenician coast.

According to Layard’s personal notes of the nearby scenes, this city “stands amongst mountains which rise from the seashore.” He also recorded that the area close to the city was forested. While Tyre and Jaffa were coastal cities, both were built on flat terrain and neither was forested.

Compton argued that the city described is Ushu, one of the eight Phoenician cities mentioned in the annals, and the only one mentioned twice. Compton then went one step further and equated ancient Ushu with the ruins of Alexandroschene, named after Alexander the Great, located halfway between Tyre in Lebanon and the modern border of the State of Israel. Alexandroschene exists on a promontory, which also happens to be the only place on the southern Phoenician coast where mountains descend to the edge of the Mediterranean Sea.

Indeed, as noted in the paper, Compton added that all eight other Phoenician cities retain their names throughout ancient times. Ushu, however, falls out of use in antiquity, and the name Alexandroschene, the staging ground from which Alexander the Great assaulted the island fortress of Tyre, begins to be used.

The location of Ushu just south of Tyre also matches with a probable reference to the city as Hosah in Joshua 19:29, being between Tyre and Achziv further to the south.

Following the asor presentation, Compton’s colleague, John M. Russell, further solidified the Ushu option, reminding him that the inscription framing the entrance to the throne room only mentions one Phoenician city—Ushu, which underscores its importance and would “favor its depiction on the throne room reliefs as well.”

Put together, wrote Compton, “[t]he above confirms that the wall reliefs to the right (east) of Sennacherib’s throne, indeed, began with Phoenicia and Luli’s escape, and thus begins with the same event as Sennacherib’s annals of this third campaign. One can then hypothesize (and the rest of the evidence will support) that these reliefs followed the same chronological order as the annals.”

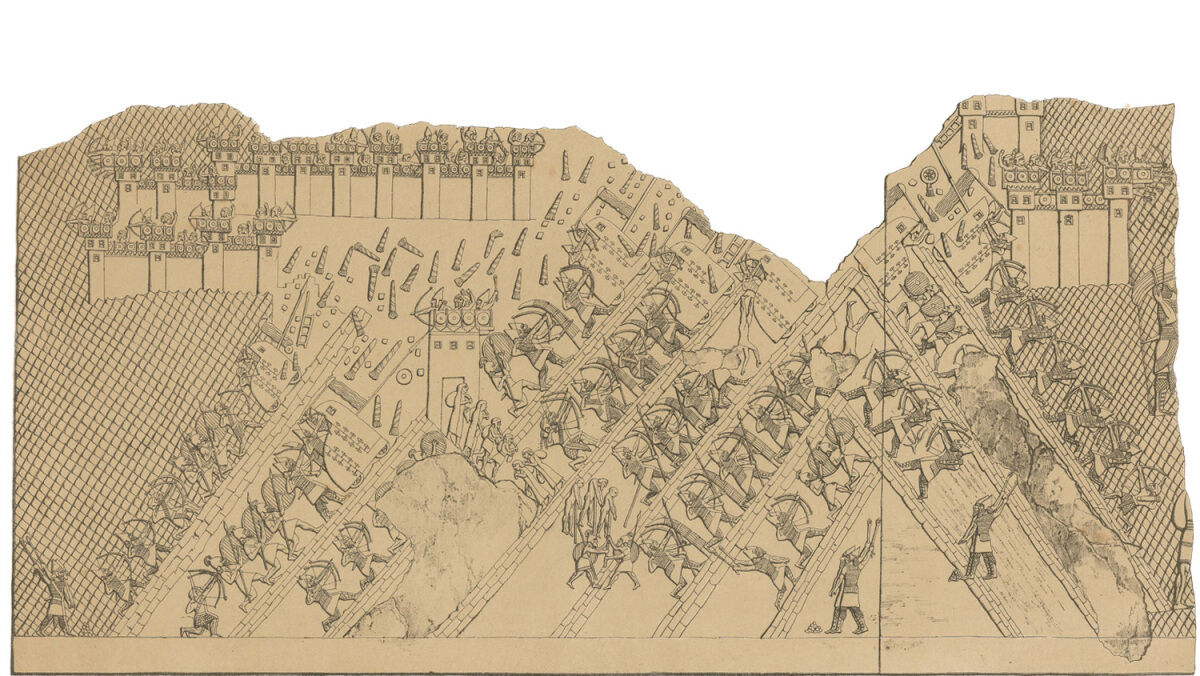

Compton then confirmed the earlier research by Russell, identifying the second of the three documented throne room reliefs (Slab 24) with the Cushite-Egyptian forces in battle with the Assyrians at Eltekeh. This corresponds with the more descriptive written records in the annals that describe Sennacherib’s army moving further south to take over Philistia.

According to the annals, the Philistines call for help from the Cushite-Egyptian army, which enters the fray in the battle at Eltekeh, a location on the coastal plain just to the west of modern-day Rehovot. Given Slab 24 is the only carving displaying an open battle, and its place within the Philistine section of the annals, it makes logical sense that Slab 24 is the Eltekeh battle. The city of Eltekeh is identified today with Tel Shalaf, which is an extremely small tel that Compton matched with the tiny city in the background of the open battle scene.

Here’s what we know so far: The first scene in the throne room is identified with Ushu, representing the first nation to be conquered on Sennacherib’s third campaign. The second scene is identified as Eltekeh, Sennacherib’s major battle in Philistine territory and second step in Assyria’s Levantine invasion.

Why is this important in our consideration of Jerusalem? “Since the first two scenes have been shown to depict scenes from the first two kingdoms invaded on Sennacherib’s third campaign,” Compton wrote, “Slab 28 might be expected to feature Sennacherib’s third and final target of this campaign—Judah” (emphasis added).

Jerusalem Revealed!

Given the progression of the throne room reliefs, and the fact that Jerusalem is the only Judahite city to be mentioned by name in Sennacherib’s annals, logic suggests we can expect Hezekiah’s royal city to appear next in the wall reliefs in Nineveh.

As noted in the introduction, the visual evidence identifying the city in Slab 28 as Jerusalem is compelling.

In his article, Compton drew attention to the striking architectural similarities between Slab 28 in the throne room and the Lachish wall reliefs from Room 36—the only other Judahite city that has been unquestionably identified in Sennacherib’s palace. In particular, the masonry at the top of the defensive towers between Lachish and the city of Slab 28 is almost identical. “Both cities have tall narrow towers topped with sophisticated battlements that are corbeled (or otherwise extended beyond the width of the tower that supports them),” wrote Compton. While other cities in the southern Levant were shown with single-corbeled towers, only on these Judahite cities do the towers extend outward, wider than their base a second time, indicating that this is a unique defining element of Judean architecture.

Outside of Slab 28 and the Lachish reliefs, the only other time this architectural feature exists on Assyrian reliefs is in an unidentified city displayed in Room 12 of Sennacherib’s palace. These reliefs show a moat wrapping partway around a city but ending where a river flows along the city’s left side. Compton identified this Room 12 city with Tell es-Safi (the biblical city of Gath), where a massive trench had been carved through solid rock around three sides of the city, while a river flowed along the fourth side. Previously, researchers Alexander Zukerman and Itzhaq Shai showed that Tell es-Safi/biblical Gath was the unnamed city with a moat that Sennacherib described conquering in his famous Azekah inscription. In this inscription, Sennacherib called it a Philistine city that had been “captured and strengthened by Hezekiah.” This is also supported by the archaeology of Tell es-Safi, which shows a Judahite phase during the time of Hezekiah when the city came under Judahite domination (for more information, see “Hezekiah’s Occupation of Gath”). It was at this time that the Judahite-style upper battlements may have been placed on top of the defensive towers.

Put together, in all of the Assyrian wall reliefs, there are only three cities with multi-corbeled battlements atop their defensive towers. One of them is definitely Judahite Lachish. The other is all but certainly Judahite Gath. The last is the scene on Slab 28 of the throne room, which Compton views as Jerusalem.

Compton also drew attention to the lone figure of a man holding a flag (or “standard”) atop the tallest tower of the city on Slab 28. He is the only human figure in the city. Studying this figure, one recalls Sennacherib’s boast on the Taylor Prism, where he describes: “Hezekiah … I shut up in Jerusalem like a caged bird.”

To Compton, the fact that this individual is holding a flag or standard indicates his royal status. Normally, Assyrian reliefs depict the enemy on city walls brandishing weapons or throwing stones. But in this case, he’s holding up a standard, which Assyrian texts closely associate with kings. In fact, Slab 28 is the only instance on Assyrian reliefs of a figure holding up a standard atop an enemy’s city wall.

As Compton related, there are all kinds of standards in Assyrian reliefs. Some take the shape of a globe or other unusual shapes. But on Slab 28, the standard is in the shape of a square cloth.

In the Bible, the Hebrew word nes is used to describe the standard (banner or flag) or a sail of a ship (see Isaiah 13:2; 33:23). In his paper, Compton related this to a passage in Ezekiel 27:7, where the nes, or sail, on a Phoenician ship can be viewed as a “square of cloth hung from a horizontal crossmember centered atop a vertical mast, much like the standard on Slab 28.”

As Compton summarized in our interview, “This is the only instance of somebody holding a standard, which I think means it is the king!” This would match perfectly with the description of Hezekiah in the annals and is another indication that Slab 28 is a scene of Jerusalem.

Bringing Jerusalem to Life

In his paper, Compton then works to establish the vantage point from where the city image was created. Through a lengthy comparison with the archaeology and geography of Jerusalem, he posited the image was drawn from north of the city. He then followed up that discussion by addressing some potential challenges to his designation of Slab 28 being Jerusalem, such as the question of direction in the throne room and the idea of a continuous narrative. These are dispatched with ease, citing similar examples of the same phenomena in other Assyrian reliefs (I encourage you to read the paper itself on this).

Congratulations to Stephen Compton for his formidable research and lucid explanation of the entire eastern wall of King Sennacherib’s throne room. While it can be difficult to reach academic consensus on almost any subject these days, Compton’s well-reasoned case for understanding the progression from Ushu to Eltekeh to Jerusalem in Sennacherib’s “palace without equal” will be hard to overturn.

For us Jerusalem-philes, we are grateful to have another crucial resource to gain insight into Judean royal architecture and the layout of Jerusalem from the time of Judah’s biblical kings. No doubt the debate will now begin, perhaps not over the actual designation of Slab 28 being Jerusalem but over the particulars of the scene itself. Surely, there is much more that can be learned about Jerusalem from this image.

I suspect that just as researchers have inspected every element of the Madaba map of Jerusalem from the Byzantine Period for clues of the city’s layout, scholars will now pore over this image time and again. We finally have an image of royal Jerusalem from 1,000 years earlier for our reference material.

And from a perhaps more important standpoint, it is truly amazing how much archaeological and textual information is now available, highlighting this episode in biblical history.

Certainly, there is a major point of divergence between Sennacherib’s annals and the biblical text found in Isaiah, Kings and Chronicles—most notably, the destruction of Sennacherib’s army on the eve of its attack on Hezekiah’s Jerusalem (Isaiah 37:36-37; 2 Kings 19:35; 2 Chronicles 32:21). Sennacherib fails to mention such a miraculous defeat of his own army. But then again, what Assyrian king (or almost any for that matter) is known for recording his failures on his palace walls or annals? This is certainly not something that would be recorded in his magnificent throne room.

This image—and the lack of destruction layer at Jerusalem—paint a clear picture and bring the Bible to life. “Therefore thus saith the Lord concerning the king of Assyria: He shall not come unto this city, nor shoot an arrow there, neither shall he come before it with shield, nor cast a mound against it. By the way that he came, by the same shall he return, and he shall not come unto this city, saith the Lord. For I will defend this city to save it, for Mine own sake, and for My servant David’s sake’” (2 Kings 19:32-34).

Afterword from Stephen Compton

“When developing a new research paper, I usually present it at an academic conference to get feedback from colleagues before submitting it to a journal. I first presented this paper at ASOR 2024 in Boston. Afterward, I had a great conversation with Brent Nagtegaal. He brings substantial knowledge and experience from his extensive work on archaeological excavations in Jerusalem and asked about how the image I was proposing to identify as Jerusalem corresponded with that city’s Iron Age II archaeological record. Researching and exploring that relationship during the subsequent rewrite improved the paper. I am grateful for that input from Brent and happy to see this paper—after undergoing peer review and publication in the Journal of Near Eastern Studies—also being shared with a wider audience here in Let the Stones Speak.