In the world of biblical archaeology, every year brings new discoveries that illustrate, sometimes transform but always inform our view of the past. And in spite of the tumultuous events in the land of the Bible, 2024 has been no exception. Here is our list of top 10 discoveries in biblical archaeology for the past calendar year.

10. Hallucinogenic Plants in Philistine Temples

In February, Bar-Ilan University researchers published a report on discoveries of various plants used in Philistine temples, including hallucinogenic plants. The report focused on two temples discovered at Tell es-Safi—biblical Gath—constructed in the 10th and ninth centuries b.c.e. and destroyed around 830 b.c.e.

Over 2,000 samples of burnt seeds and fruits were collected and tested. They derived from plants like the chaste tree—an aphrodisiac and anesthetic—and the poison darnel—a hallucinogenic fungi containing lsd alkaloids. The researchers concluded that for the Philistine worshipers, “it is plausible that temple ritual praxis included the use of medicinal and mood-enhancing additions to regular foods.” Although the Bible does not explicitly say anything about the Philistines consuming hallucinogenic drugs, Isaiah 2:6 does condemn their religious “soothsayers” (עננים)—a Hebrew word etymologically linked to the word for “clouds,” thus perhaps hinting at just how one became a Philistine soothsayer—through the ritual inhalation of hallucinogenic substances.

For more on this discovery, check out our article “Hallucinogenic Plants Discovered in Temples at Gath.”

9. Patriarchal Period Insect Dyes

On July 13, joint researchers from Bar-Ilan University and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem published a report on a 3,800-year-old textile from the “Cave of the Skulls.” When it was uncovered in 2016, researchers had been struck by the vibrant red color of the fabric. It turns out this red was unique: Though most ancient red dyes were produced from a plant root, this dye was produced from a scale insect. The use of scale insect dyes is mentioned dozens of times in the Bible, including in early contexts, such as for the tabernacle drapery (e.g. Exodus 26:1; see also Genesis 38:28 for a case relating to the sons of Judah).

Of further significance is the fact that, though there are scale insects (sometimes referred to as “scarlet worms”) native to Israel, this particular dye comes from a species found west of Israel, inhabiting regions “including Spain, France and other areas.” This fragment, then, shows remarkable evidence of wide trade connections across the Mediterranean during such an early period (the Middle Bronze Age).

For more on this discovery, read our article “Earliest Evidence of Red-Dye Textile Discovered in Judean Cave.”

8. Deep-sea Shipwreck

The discovery of the “earliest ship ever found in the deep seas” was announced in June as “history-changing.” The 3,300-year-old, roughly 13-meter-long ship was found submerged 90 kilometers from Israel’s coast—further out at sea than any other Mediterranean shipwreck from that period. The head of the Israel Antiquities Authority (iaa) Marine Unit Jacob Sharvit said: “The discovery of this boat now changes our entire understanding of ancient mariner abilities: It is the very first to be found at such a great distance with no line of sight to any landmass.”

The hull of the shipwreck contains hundreds of Late Bronze Age amphorae: Thus far, only a small representative number of the vessels have been brought to the surface, and await comprehensive research, analysis and publication.

For more on this discovery, check out our article “Earliest Deep-sea Shipwreck Ever Discovered Found Off Israel’s Coast.”

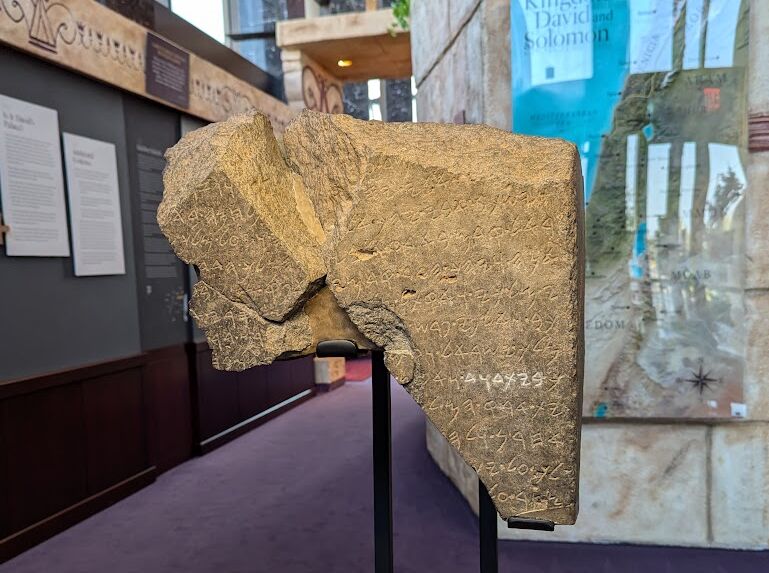

7. Rearranging the Tel Dan Stele

The Tel Dan Stele, or House of David inscription, is arguably the single most prized artifact in the world of biblical archaeology. This automatically makes any significant contribution toward the understanding of it worthy of a top 10 position. In 2024, Prof. Michael Langlois—following his research of the parallel “David” inscription on the Mesha Stele—turned his attention to the Tel Dan. Utilizing the same digital imaging techniques used on the Mesha Stele (rti—Reflectance Transformation Imaging), Langlois completed a full comparative letter-by-letter analysis of the three fragments of the stele, determining that they have been pieced together erroneously.

Certainly, all three fragments—A (right), B1 and B2 (left, upper and lower)—are part of the same stele, and based on paleomagnetic analyses it can be concluded that they are from the same side of the same stele. The issue is that while the script style is identical between fragments B1 and B2, it is noticeably different for A—showing that the A and B pieces do not go side-by-side, but probably belong to more separated upper and lower portions of the original stele. Langlois identifies the difference in style as a sign of the work of two different scribes—either that, or a single scribe’s style changing based on working at different angles on different parts of the inscription. Whatever the case, that the pieces do not go side-by-side is apparent. (For what it’s worth, none of this changes the interpretation of the key phrase found in the inscription, “House of David,” which is squarely within fragment A.)

Langlois’s report is published in the latest Israel Exploration Society journal. For more on this research, read our article “Has the Tel Dan Stele Been Reconstructed Incorrectly? New Research Suggests Yes.”

In other Tel Dan Stele news, the item is currently on display in the United States of America, outside of Israel for only the second time ever. Having just left our own ongoing exhibit “Kingdom of David and Solomon Discovered,” it is currently on display at the Jewish Museum in New York for the next several weeks (facilitated through the Armstrong Institute and Armstrong International Cultural Foundation, as part of the loan agreement). Relevant to this and our number one discovery, our exhibit in Edmond, Oklahoma is still ongoing—for those who wish to visit, see here for details.

6. What Mmst Must Mean

The lmlk “to the king” pottery handle inscriptions from the late eighth century b.c.e. are well known, and examples number in the thousands. The First Temple Period Judean inscriptions, generally attributed to the reign of King Hezekiah and his siege preparations in advance of Sennacherib’s Assyria invasion, typically bear one of four different inscriptions: Hebron, Socoh, Ziph and Mmst. The first three are the names of well-known Judaean cities. But the name Mmst has remained a mystery, ever since the first example was discovered more than 150 years ago. A typical assumption has been that it, too, must refer to a city, as-yet otherwise unknown biblically or archaeologically.

Wonder no longer. In a paper published in June in the Jerusalem Journal of Archaeology (jjar), epigrapher Dr. Daniel Vainstub concluded that linguistically, based on the rules of Semitic languages, Mmst cannot be a proper noun referring to an Iron Age Judaean city. Instead, it is a phrase reading “from [the] mas’et”—referring to a separate Hezekiah-period taxation effort, such as that described in 2 Chronicles 31:4-20. While Mmst would represent a slight abbreviation of this phrase mnms’t, Vainstub demonstrates some examples of otherwise-overlooked jar handles inscribed in the longer form, thus confirming his interpretation as correct.

For more on this research, read our article “After 156 Years, Has the Mmst Mystery Finally Been Solved?”

5. Tabernacle Gold at Shiloh

It would not be a top 10 list if it did not include Israel’s tabernacle site, Shiloh. And once again, Dr. Scott Stripling and his Associates of Biblical Research team have not failed to deliver—although reporting on this item (or these items) has for now been minimal. Within a favissa (sacrificial burial pile) located along the edge of the tel—in use during the period in which the biblical tabernacle stood—a number of small star-shaped token gold “offering” items were discovered, including one impressive piece with a face engraved on it. For now, news of this discovery has been largely limited to our interview with Dr. Stripling at Shiloh earlier this year, as well as discussion on the Associates for Biblical Research channel. Details and pictures of this gold-faced guy from Shiloh are planned to be published in due course; aiba will keep you informed. (This is a discovery that may find its way to others’ top 10 lists for 2025—you got it here first!)

For now, check out our interview with Dr. Stripling at Shiloh here and an in-house Associates of Biblical Research interview here.

4. Another Seal From Jerusalem

In August, the iaa announced the discovery of another seal from First Temple Period Jerusalem. In the words of excavation directors Dr. Yuval Baruch and Navot Rom: “The seal, made of black stone, is one of the most beautiful ever discovered in excavations in ancient Jerusalem and is executed at the highest artistic level.” The seal dates toward the end of the First Temple Period and bears a winged figure framed by a paleo-Hebrew inscription reading, “Belonging to Yehoezer, son of Hoshayahu.”

Some have suggested that this seal may belong to a biblical figure. Jeremiah 43:2 mentions “Azariah the son of Hoshaiah.” The names of the fathers are the same (הושעיה and הושעיהו—the name on the seal simply uses the longer theophoric ending, but this is typical and interchangeable). The initial names actually are similar in Hebrew, simply switching the first and last halves of the name (עזריהו and יהועזר), effectively rendering the same meaning.

Whether or not the individuals are one and the same, the numerical significance of this discovery remains. As accounted in a recently published corpus of First Temple Period inscriptions from Jerusalem (co-authored by Armstrong Institute contributor Christopher Eames and Hebrew University’s Yosef Garfinkel), this seal brings the total for the city to 36; by contrast, the next highest number of seals comes from the city of Arad, with just five; followed by Lachish, with four. This alone demonstrates the administrative importance of Jerusalem as capital of the region.

For more on this discovery, read our article “Another First Temple Period Seal Found in Jerusalem—Could It Belong to a Biblical Figure?”

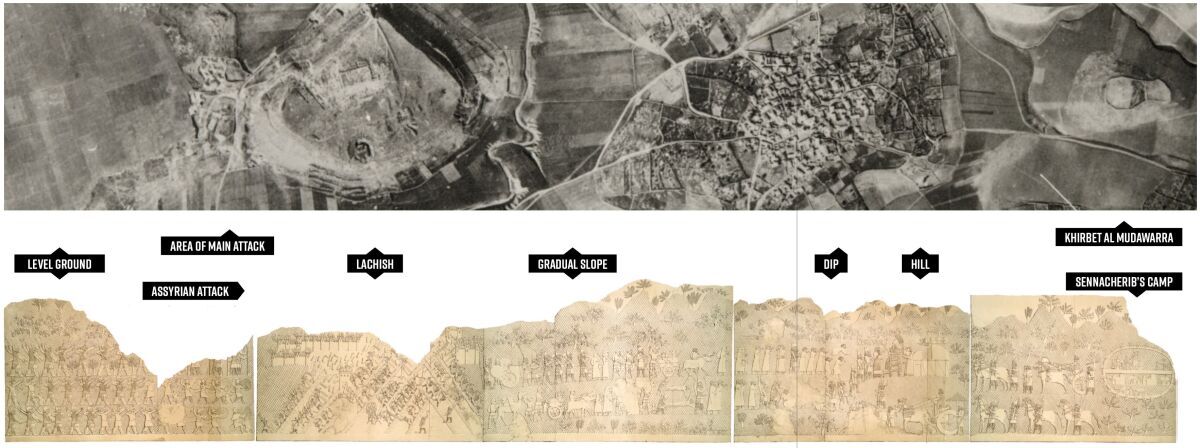

3. Compton’s Assyrian Camps

The Assyrian conquest of Judah is one of the most well-attested biblical events in Near Eastern antiquity. And the remains of the besieged Tel Lachish, Judah’s “second city,” stand out as some of the best attestation to the event. (Not Jerusalem, though. Archaeological excavations have revealed no evidence of destruction at the capital city, just as the Bible describes.) But where did the invading monarch set up his camps?

In June, independent researcher Stephen Compton published an article in Near Eastern Archaeology purporting to show exactly where Sennacherib’s siege camp at Lachish was located. Taking the famous relief depiction of Lachish at Sennacherib’s Nineveh palace literally, Compton overlaid the imagery onto an early aerial photograph of the undeveloped landscape, showing Sennacherib’s military camp to be located with the strikingly similar outline of a site on the distant hill of Khirbet al-Mudawarra. Though investigation of the site has been minimal—with some evidence linking it to the time of Sennacherib—if confirmed, this would be the first time an Assyrian camp has been identified in Israel.

But Compton does not settle for one Assyrian camp. He goes on to identify a “trail of Sennacherib’s siege camps” throughout the land, many of them at sites also named Mudawarra in the Arabic language (a reference to a “camp of the invading king”). Compton identifies these historic names as potentially preserving the memory of the original Assyria path of conquest. Most notably, he proposes a site in Jerusalem itself as the base of Assyrian operations in preparing for a siege of Jerusalem that never materialized.

While the Lachish identification is the most likely, Compton has had his detractors. But stay tuned because there is something along these lines coming down the pipeline that is quite remarkable. For more on the current research, check out “The Assyrian Military Camp at Lachish—and Maybe at Jerusalem Too: An Interview With Stephen C. Compton.”

2. Carbon-dating David’s City

Debate has raged for the last two decades as to whether or not certain monumental structures discovered in Jerusalem date to the 10th century b.c.e.—the time of David and Solomon—or to the ninth century, long after the legendary rule of these biblical kings. Those in the latter camp often argue that 10th-century Jerusalem was a poor, unpopulated backwater—certainly nothing like the glorious capital described in the Bible.

Specific debate about certain structures aside: In April, a new, landmark carbon-dating study of Jerusalem was published in the journal pnas. Titled “Radiocarbon Chronology of Iron Age Jerusalem Reveals Calibration Offsets and Architectural Developments,” it demonstrated, from a new and entirely novel perspective, that the Jerusalem of the time of David and Solomon was indeed a city. In Haaretz’s rather glorious summary (a paper known for a minimalist bent toward David and Solomon), this “[f]irst broad radiocarbon study of Jerusalem casts doubt on the paradigm that King David’s capital was a just small village …. It already extended over a vast area more than 3,000 years ago.”

That said, the study was not solely concerned with the 10th century b.c.e. More broadly, it derived over 100 carbon samples from Iron Age layers spanning 1200 to 586 b.c.e. at several different locations within Jerusalem’s City of David. Of the randomized samples—mostly seeds—almost 20 percent of them dated to the early part of the Iron Age (12th to 10th century b.c.e.), “clearly indicat[ing] widespread occupation of yet undetermined character, often underestimated due to the limited architectural contexts attributed to this period.” Although the study did not seek to date individual structures of particular centuries, the quantitative analysis does reveal that the city was densely inhabited at that time.

Another key takeaway from the study is a new proposition for the dating of Jerusalem’s westward expansion, often attributed to Hezekiah during the late eighth century b.c.e. The study concludes that this expansion must have taken place earlier than initially thought—perhaps as early as the first half of the ninth century b.c.e.

For more on the research, read our article “A Revolutionary Carbon-Dating Study of Ancient Jerusalem.”

1. Phoenician Presence in Solomonic Jerusalem

Go ahead and accuse us of bias in putting one of our own discoveries in first place, but it has made it into the top three of other lists out there, and not without merit! Not only is this 10th-century b.c.e. item the earliest gold piece ever found in Jerusalem, it’s the best evidence yet of a direct Phoenician presence in Solomonic-period Jerusalem, something attested to in several scriptures, including descriptions of servants, craftsman, royal wives and even goldsmiths.

Known as the Ophel Electrum Basket Pendant, this tiny piece of jewelry—a portion of an earring pendant—was first discovered during our 2012 excavation on Jerusalem’s Ophel with the late, great Dr. Eilat Mazar, in the area of supervisor and Armstrong Institute contributor Brent Nagtegaal. The item was not, however, noticed in the field but was first discovered during the sifting process, following which it was packaged up and stored for later study.

Over the years, the item sat in storage, overlooked by the study and publication of other major discoveries, the likes of the bullae of Hezekiah and Isaiah, and monumental 10th-century architecture (not to mention the final years of ailing health for Dr. Mazar and the transition of study following her death). Finally, on a visit to Dr. Mazar’s office, Brent noticed for the first time this artifact that had been uncovered via the later wet-sifting of material from his area—and the rest is history.

Nagtegaal teamed up with Dr. Amir Golani, an expert on Phoenician jewelry of this specific type, and together they published the discovery in the 2024 volume of the City of David Studies of Ancient Jerusalem (Hebrew language). In short: The earring pendant is of a type very specific to Phoenician sites, as found in the Levant and throughout the wider Mediterranean. The item is of a highly personal (and possibly even religious) nature, a veritable cultural marker of the wearer. As such, it is evidence of direct Phoenician presence in Jerusalem—and given the specific layer on the Ophel in which it was found, during the 10th century b.c.e. no less—the time of Solomon, during which he expanded the city north onto the Ophel and beyond. “And Hiram King of Tyre sent his servants unto Solomon” indeed (1 Kings 5:15).

For more on this discovery, check out Brent’s article “The Golden Earring Pendant of Jerusalem.” And if you’d like to see this artifact in person, it can be seen at our exhibit “Kingdom of David and Solomon Discovered” in Edmond, Oklahoma, where it is on display for the first time in 3,000 years—since the days of Solomon. Look closely though—or you’ll miss it. The craftsmanship for such a minuscule item is extraordinary—small wonder Solomon sought the contribution of Phoenicia’s goldsmiths (2 Chronicles 2:14).

Read Our Previous Lists

Top 10 Biblical Archaeology Discoveries of 2023

Top 10 Biblical Archaeology Discoveries of 2022

Top 10 Biblical Archaeology Discoveries of 2021

Top 10 Biblical Archaeology Discoveries of 2020

Top 10 Biblical Archaeology Discoveries of 2019

Top Biblical Archaeology Discoveries of 2018