Numerous exciting archaeological discoveries were made in 2019, including a number of biblically significant artifacts. Following is a list of what we regard as the top finds for the year.

Early Evidence of the Kingdom of Edom

The Bible states that the kingdom of Edom was formed long before the kingdom of Israel (Genesis 36:31). But Bible skeptics had assumed that the southern kingdom of Edom was established, from previously nomadic tribes, many centuries later—sometime well into Iron Age ii, Israelite kingdom period. This year, that theory was put to rest following excavations at two Edomite copper mines: Timna and Faynan. Analysis of slag deposits—a by-product of the copper mining process—showed that the Edomite mines were run by a functioning state, with a centralized authority, long before the Israelite monarchy—from at least 1100 b.c.e., and probably earlier.

It is known that both of these mines were in operation some 300 years before the reign of David, and were initially operated by the Egyptians (whose empire covered the territory of Edom and exerted some degree of influence over Israel during the period of the judges). But during the 12th-century Bronze Age Collapse, Egypt withdrew and the native Edomites took over control of copper production.

This transition is clearly witnessed in the strata of slag deposits. This new, centralized native authority utilized different processing techniques to the Egyptian overlords—new techniques that, over time, gradually developed in parallel manner at both sites, attesting to mining standardization and a centralized authority that controlled sites vast distances apart.

Further, strata dating from circa 1000 b.c.e. onward show another significant change—a change in buildings, clothing and diet, and a peak in copper production. The Bible states that it was at this period that David conquered and controlled Edom (2 Samuel 8:14)—and that his son Solomon imported vast quantities of bronze (an alloy of copper) to build the temple. Another change is witnessed at the end of the 10th century b.c.e., specifically in buildings and animal transport—this too fits with the biblical account (as well as the Karnak relief), describing the Pharaoh Shishak’s invasion of Judahite-owned territories (2 Chronicles 12).

Nathan-Melech Bulla

A bulla (clay seal-stamp) belonging to a biblically-named individual was discovered this year at Jerusalem’s Givati Parking Lot excavations. Discovered in a layer dating to the seventh century b.c.e., the text on the bulla reads: “Belonging to Nathan-Melech, Servant of the King.”

The name Nathan-Melech appears only once in the biblical account (2 Kings 23:11). He was a royal servant (his exact position is unclear—most likely a chamberlain or eunuch) in King Josiah’s royal court. Nathan-Melech occupied a chamber near to the temple entrance, adjacent to a court in which the pagan Judahite kings had established a place of sun worship, notably featuring horses and chariots dedicated to the sun. It is unclear what kind of sympathy Nathan-Melech may have had to this pagan worship.

The bulla dates to this very time period (seventh century b.c.e.), and thus with a matching name, royal position, dating and findspot, confirms the existence of this individual.

‘We Have Found Biblical Ziklag’

These were the words declared in the press release by the Khirbet a-Ra’i excavation team. A square kilometer of excavations at the tel has revealed evidence, according to the excavators, that this is indeed the long “lost” biblical city.

Ziklag was originally a Philistine city, unusual in that it was handed over to David and his men as a gift, while they were on the run from the Israelite King Saul (1 Samuel 27:5-6). Up to a dozen different sites have been suggested as candidates for this biblical city. Khirbet a-Ra’i closely fits the bill.

The city is located near Israel’s border in what would originally have been Philistine territory, and shows heavy evidence of Philistine settlement from the 12th–11th centuries b.c.e. However, dating to around the start of the 10th century, the pottery remains change to those of a Judahite settlement—and with no sign of conflict or destruction. Evidently, the city changed hands in a peaceful manner, to Israelite control—with artifacts precisely paralleling those found at another, well-established “Davidic” site—Khirbet Qeiyafa.

Further, during the period of Judahite occupation, the city witnessed a fiery conflagration. This, too, fits with the biblical account—while David and his men were out on an expedition with a Philistine king, the Amalekites entered Ziklag and “burned it with fire” (1 Samuel 30:1), taking the women and children captive. David and his men quickly routed the invaders, and reclaimed their families and possessions.

Whether or not Khirbet a-Ra’i is indeed the biblical Ziklag, it is another incredibly important location that adds to the growing number of Davidic-era cities (such as the City of David, Khirbet Qeiyafa, Tel ‘Eton, Timna, Tel Dan and Geshur), disproving minimalist theories about the supposedly limited extent of David’s kingdom of Israel during the 10th century b.c.e.

DNA Study Confirms Philistine Origins

Ashkelon is one of the five primary cities of the Philistine pentapolis. And excavations over the past several years have uncovered the first-ever Philistine cemetery—allowing, for the first time, a full formal dna analysis of the Philistines.

Scientists and historians have long speculated as to where the Philistines came from. The Bible states that they were from the land of Caphtor (Jeremiah 47:4; Amos 9:7). This is identified as the island of Crete.

The dna samples taken from the Philistine bodies, dating to circa 13th century b.c.e. (around the time of a significant Philistine migration), showed that they were most closely matched to a south European population, specifically—surprise, surprise—inhabitants of the island of Crete.

Goliath-Era Gath

Tel es-Safi, a Philistine site identified as the biblical Philistine capital Gath—the hometown of the giant Goliath—is excavated on an annual basis. Summer excavations this year, though, proved especially significant.

An older layer of habitation was found—and one that proved more gigantic than anything as yet discovered at the site. The city layer that the excavators had been exposing dated to the end of the 10th century (around the time of Rehoboam). This one dated to the Iron i period—the time of King Saul and a young David.

“I’ve been digging here for 23 years, and this place still manages to surprise me,” lead excavator Prof. Aren Maeir of Bar-Ilan University told Haaretz on July 24. “All along we had this older, giant city that was hiding just a meter under the city we were digging.”

It was in this city—according to the biblical account—that Goliath would have lived; that the ark of the covenant would have traveled to, spreading disease and devastation; that David entered, while on the run from King Saul.

And this Iron i-level city is, truly, fit for giants. Walls stood over four meters thick, with some individual stones up to two meters in size. Stronger, fired mud bricks were used, rather than the typical sun-baked ones. The city was evidently more colossal than any other thus far discovered in the Levant dating to this period. It certainly attests to the powerful dominance the Philistines exerted over much of Israel at this time (1 Samuel 10-13).

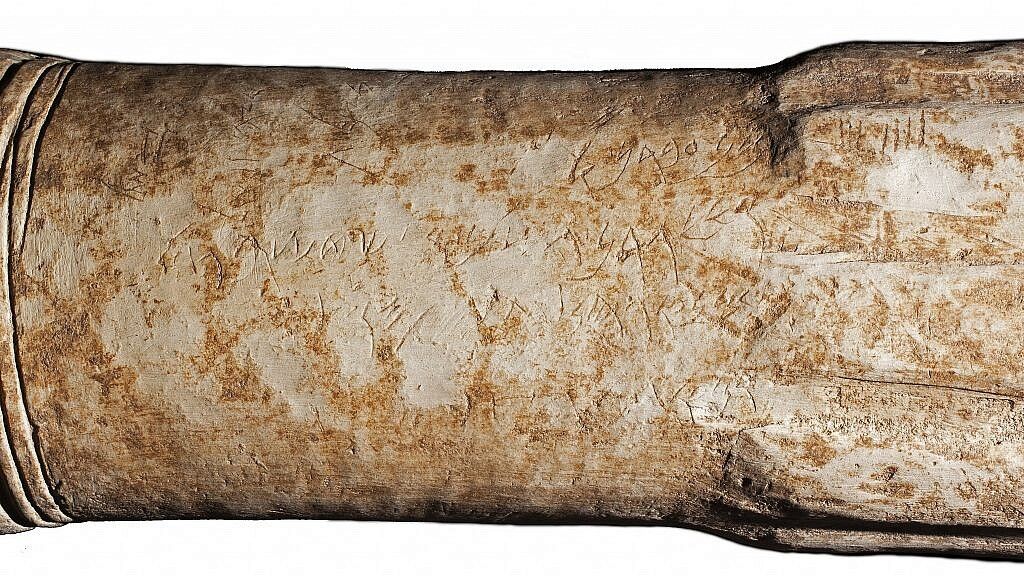

Moabite Altar Inscription

This Moabite stone altar stand had been excavated nearly a decade ago, at the Jordanian site of Khirbet Ataruz (biblical Ataroth). But it was only this year that the two inscriptions on it were translated. The text provides evidence for the early Moabite nation; demonstrates a developing, independent Moabite script; reveals the nation’s cultic practices; and significantly, helps fill out the biblical account of 2 Kings 3. Primarily, though, the artifact was hailed by its translators as containing—potentially—the earliest reference to “Hebrews.”

The Bible, as well as the famous Mesha Stele, relates that the Israelites of the tribe of Gad had long occupied the once-Moabite stronghold of Ataroth. 2 Kings 3 describes a rebellion by the Moabite King Mesha, in which—according to the Mesha Stele—King Mesha managed to retake Ataroth.

This fragmentary altar inscription describes the defeat of an army and the taking of plunder from “Hebrews”—treasure that, according to the inscription, was apparently then offered at the dedication of a cultic temple, within which the altar stand was found. Evidence at the site, together with the Mesha Stele and biblical account, suggests that this pagan temple was, in fact, an Israelite “high place,” and that perhaps this very altar stand was an Israelite one, inscribed secondarily in Moabite script (see 1 Kings 22:43).

This suggested identification of the term “Hebrews” would thus make the Ataruz altar the earliest known inscription to mention the term (excepting the 14th century use of the term Habiru, in the Amarna letters). The altar stand would constitute the earliest alphabetical inscription with the name).

The Bible relates that this victorious Moabite rebellion—as commemorated on the altar pedestal and Mesha Stele—was short-lived; a united Israelite, Judahite and Edomite force proceeded to invade Moab and decimate the armies of King Mesha, following miraculous intervention from God through the Prophet Elisha.

Special Mention

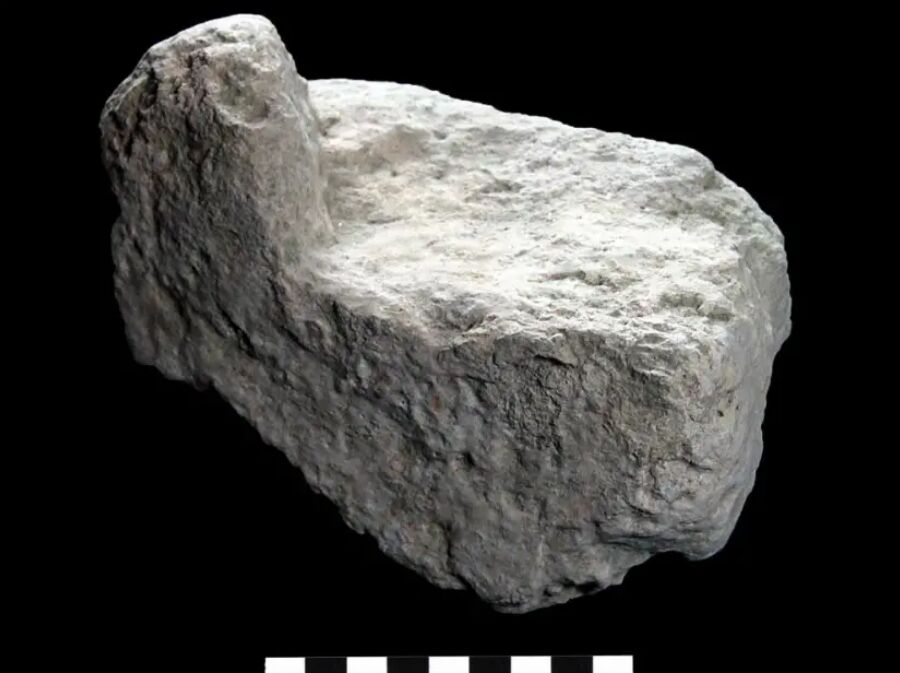

There are a number of other discoveries made this year that deserve special mention. Continuing excavations at the biblical tabernacle site of Tel Shiloh have revealed three stone “altar horns,” biblically commanded cornerstones, that may have been a part of an Iron i altar used at the time of the tabernacle. Excavations at Kirjath-Jearim—the place where the ark of the covenant once resided—have revealed a massive raised platform, which archaeologists speculate may have been a shrine linked to the ark. Further, regarding the ark: A large, 3,100-year-old ritual stone table slab was discovered at Beth Shemesh. The Bible describes the ark being placed on a “great stone” in Beth Shemesh, at around this time period. Could this have been the stone that the ark of the covenant rested on?

Excavations at Robinson’s Arch, near the Temple Mount, revealed a bulla bearing the biblical name Adonijah, with the then common occupational title “Royal Steward.” Excavations at Tel Shikmona have revealed that it was the first-discovered biblical-period facility for the mass production of purple-dyed textiles—an unusual color used so often in the Bible. Excavations at Tel Hadid revealed two cuneiform tablets, proving the presence of the Samaritan people imported into the northern kingdom, following the defeat and deportation of the Israelites by the Assyrians. And in a poetic moment, Israel Defense Forces soldiers on an education outreach unearthed a watchtower belonging to their 2,700-year-old contemporaries, who served under King Hezekiah.

Outside the realm of biblical archaeology—but directly relating to it—there have been a number of interesting genetic and palaeontological discoveries. The discovery of an ancient, legged snake species, which disproved one of the main evolutionary theories about snake development, and further attests to the Genesis 3 account (see our article on legged serpents here). And a genetic study that indicated (much to the astonishment of the researchers!) that some 90 percent of all animal species, as well as humans, descended from single ancestors that all began reproducing at roughly the same time, in relatively “recent” history.

And More …

This is just a short selection of the exciting artifacts discovered during 2019. Beyond that, 2019 has been a big year for aiba staff, hosting the continuation of the world-premiere exhibit “Seals of Isaiah and King Hezekiah Discovered” at Armstrong Auditorium in Edmond, Oklahoma. The successful exhibit concluded earlier this year, but the online version can be seen at the above link. We’ve also begun a new bimonthly magazine covering biblical archaeology.

We’ve also produced a number of articles this year on already existing artifacts and other archaeology-based subjects. Subjects like the scientific evidence for the prehistoric world, closely paralleling the Genesis account of creation; the archaeological evidence for Jerusalem’s first and second temples, as well as the tabernacle; wider evidence for King Josiah’s righteous “renaissance”; possible evidence for the plagues of Egypt; the earliest mention of the name “Israel”; and what evidence is there for the biblical prophets? We also wrote on the wonder of childbirth—comparing the evolutionary explanation for the difficulty of human childbirth with the biblical, and examining related archaeological discoveries. We examined the biblical animals—some would say camels prove the Bible false. Do they? We also began a podcast series examining the modern identity of the deported “Lost 10 Tribes” of Israel. Where is modern-day Reuben? Dan? What happened to Judah? And much more.

To see our top finds from previous years, click the following links: 2018, 2017, 2016. We eagerly anticipate the discoveries of 2020. Thus far archaeology has yet to yield a single, honest shred of evidence disproving the Bible. What it has done is disprove people’s misconceptions about what the Bible says. Over the past millennia, including 2019, we have seen the Bible validated, illustrated and clarified. We expect more of the same in 2020.