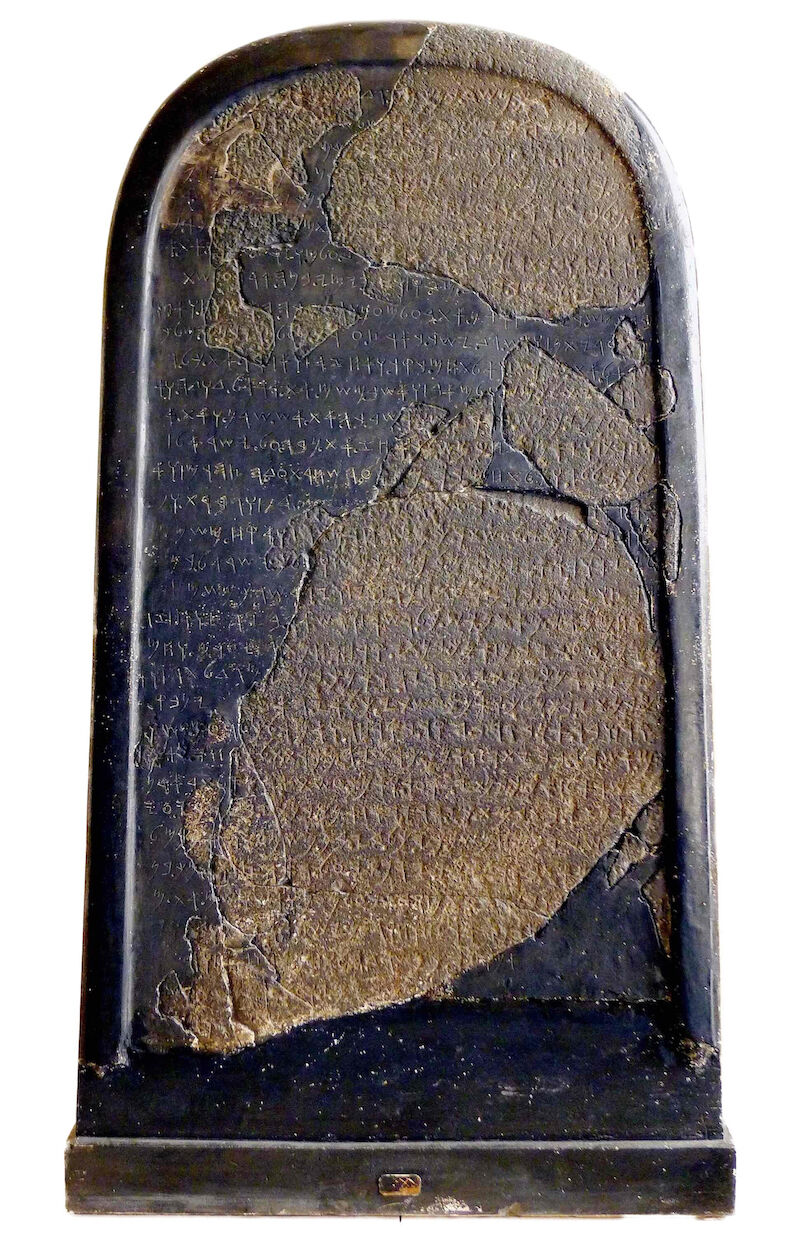

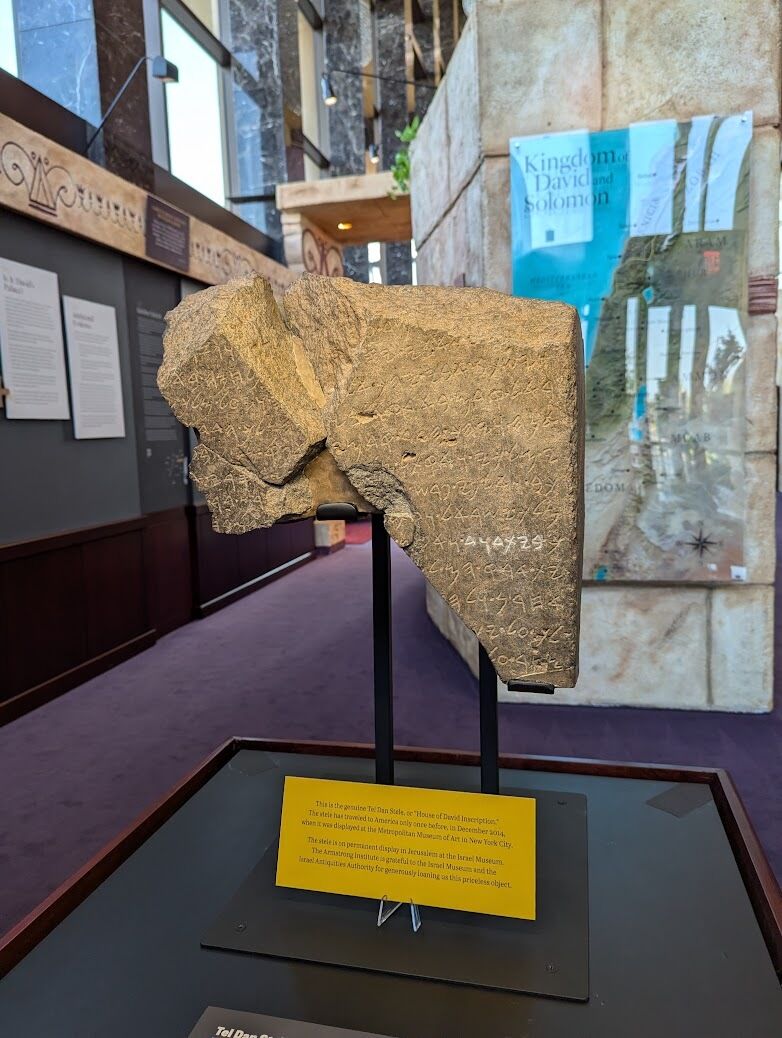

Just when you thought you knew everything there is to know about the Tel Dan Stele (the famous ninth-century b.c.e. inscription referencing the “House of David”)—and just as it comes off of display at our own exhibit, “Kingdom of David and Solomon Discovered”—along comes a revolutionary surprise.

Prof. Michael Langlois has gained some renown for his forensic-level study of the Mesha Stele (ninth century b.c.e.), confirming that the monolith does, indeed, mention King David—becoming the second confirmed inscription to do so. (His compatriot Prof. André Lemaire may beg to differ on this, given that he first proposed the reading before the Tel Dan Stele was ever discovered!)

Now, Langlois has turned his attention to the very “House of David” inscription itself—the Tel Dan Stele. It’s an artifact that has become arguably the most famous piece in the world of biblical archaeology. And in the latest issue of the Israel Exploration Journal (Vol. 74, No. 2), Langlois has produced a consequential new assessment of it.

No, the new analysis doesn’t change anything about the reading of the “House of David” phrase on the stele. Rather, it reinterprets how the three main fragments of the stele go together—or, perhaps more accurately, how they don’t go together.

A, B1 and B2

The larger triangular chunk of the stele was found in 1993 during the excavations of Avraham Biran at Tel Dan. This piece, fragment “A,” contains that now-famous phrase, “House of David,” in addition to the earliest-attested mention of the phrase “King of Israel.” In 1994, two additional chunks of the inscription were found—smaller pieces, termed fragments “B1” and “B2.”

The three pieces were clearly part of the same victory stele inscription. All were of the same basalt composition, and paleomagnetic analyses revealed the magnetic fields of the fragments to be oriented in the same way—thus, not only do the fragments generally belong to the same monument, they belong to the same side of the same monument.

Following his research on the Mesha Stele, Langlois was invited to study the Tel Dan Stele, to see if any more juice could be squeezed out of the already thoroughly researched artifact. He turned to the same digital imaging techniques used on the Mesha Stele (rti—Reflectance Transformation Imaging) to see if any more accurate readings or revisions could be given to the inscription. What he discovered came as a big surprise. “It was quite unexpected,” he told Brent Nagtegaal in a recent interview on our podcast Let the Stones Speak. “It came as a shock.”

In short, comparative analysis of the script of fragments A, B1 and B2 reveal that while B1 and B2 on the left side do clearly go together as traditionally displayed, fragment A on the right does not—and appears to be the product of another scribal hand altogether. This means that the A and B portions logically come from different parts of the inscription entirely.

Langlois explained his discovery in detail in his iej article, “The Tel Dan Inscription After 30 Years: A Fresh Look.” In it, he laid out a comparative table of all the letter forms found on each of the individual fragments. While at a glance, the script across all three looks similar, closer inspection reveals a significant number of peculiarities. The letter forms on B1 and B2 are consistent and identical—yet there are marked differences to the forms found on A, for a significant number of letters. For example, on fragment A, the lower part of the ב letters are always accomplished with a single, curving stroke; on fragments B1 and B2, in every case they are accomplished with two straight lines. On A, the lower strokes of the כ letters are straight; on B, they are curved. On A, the ל letters are more angular, each formed with two clear strokes; on B they are curved, each formed with a single stroke. On A, the upper part of the ר letters are more open; on B, they are more closed.

“The evidence presented here is cumulative and conclusive,” Langlois wrote. “There is a definite change in handwriting between fragment A, on the one hand, and fragments B1 and B2, on the other hand. … Once it becomes clear that the script is different, it is hard to unsee it.” He credits other scholars who had also previously noted certain such differences when analyzing the script of the Tel Dan Stele, and who had themselves called for a more comprehensive future analysis:

This is not the first palaeographical chart of the Tel Dan inscription, but it is the first time a synoptic comparative chart is presented. … The need for such a chart was already pointed out by [the late Prof. Walter E.] Aufrecht (2007) ….

When the two new fragments were published in 1995, few scholars suggested that they were inscribed by another engraver, sometimes for the wrong reasons. Yet they were right in pointing out script differences. Thanks to new imaging techniques, these differences are easier to spot.

Langlois demonstrates that we now indeed have proof of the work of two different scribes; either that, or the possibility of a single scribe “whose handwriting evolved for some reason”—perhaps based on his position in relation to the different parts of the stele. Either way, the result is the same: Logically, the three pieces do not interlock in the way they have been reconstructed, directly alongside one another. Certainly, one scribe is not repeatedly switching mid-sentence with another scribe; nor is his script changing so significantly along the same lines. The A and B sections of the stele, then, belong elsewhere in relation to one another.

When the Shoe Doesn’t Fit

“When I discussed this issue during the [Hebrew Union College] conference, a restorer who glued the original fragments, as instructed by Biran and Naveh at the time, confirmed that fragments A and B1 do not really join, as opposed to B1 and B2.” This was admitted by Biran and Naveh in 1995: “Fragments A and B cannot be joined in an obvious, unequivocal way” (“The Tel Dan Inscription: A New Fragment”). Still, the reconstruction team put the pieces together in what seemed to be the most logical reconstruction at the time, considering the flow of the text and a posited connection point at the back of the stone blocks.

Langlois concluded:

[T]his means that the placement suggested by the editors must be abandoned: fragment B does not continue the lines started by fragment A.

This conclusion came as a shock to me. I had never done first-hand research on the Tel Dan Stele, and I reached this conclusion independently, using new imaging techniques and digital tools.

This conclusion would be contradicted if there was a clear joint between fragments A and B, or if textual reconstruction of the inscription requires the placement adopted by the editors. However, it turns out that there is no real joint between fragments A and B1, and one can quite easily create a textual reconstruction with other placements. The cumulative evidence thus suggests that fragments B1 and B2 should be placed elsewhere.

So, what will become of the Tel Dan Stele and the manner in which it is displayed? Time will tell. Part of the latest research—the 3D scanning—was only accomplished as a product of taking the item off display, in order to prepare it to be shipped to our exhibit in Edmond, Oklahoma. Will we see fragments A and B ultimately detached and displayed alongside one another? And what will this mean for future reconstructions of the text? A Pandora’s box opens.

Meanwhile, preparations are underway for a 2025 excavation season at Tel Dan. Perhaps, by some miracle, we will soon have something more to fill in the inscription’s only widening gaps.