10. King Herod’s Staircase and Gold ring

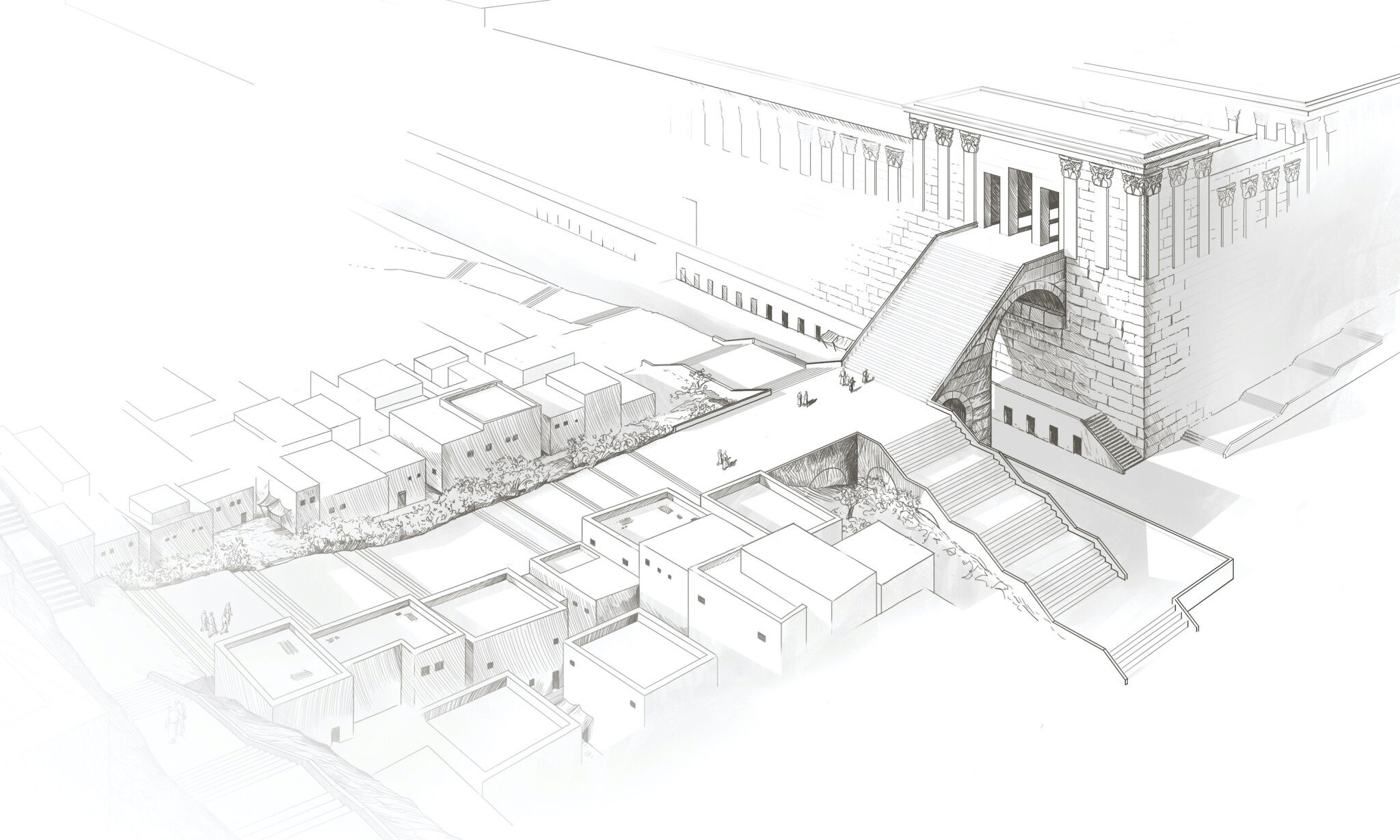

Robinson’s Arch is one of Jerusalem’s most iconic archaeological features. Named after the biblical scholar Edward Robinson, who first identified the arch in 1838, this 15-meter-wide archway juts out of the Western Wall some 20 meters above ground level.

Archaeologists have debated its original design and purpose for decades. In March 2021, less than two months before she died, archaeologist Dr. Eilat Mazar published new evidence demonstrating a revolutionary design that suggests the colossal stairway built by King Herod in the first century was far grander than originally believed.

In her final book, Over the Crossroads of Time: Jerusalem’s Temple Mount Monumental Staircases, Dr. Mazar concluded that the famous arch was actually part of a monumental four-way staircase. Prior to this, archaeologists assumed it was merely a standard stairway to street level, with either one or two entrances. If Robinson’s Arch was part of a giant four-way staircase, as the new evidence suggest, then it is utterly unique among ancient classical architecture.

In her final book, Dr. Mazar also published the discovery of a 2,000-year-old miniature gold ring from her grandfather’s excavations,

which had not yet been revealed to the public. The tiny “baby’s ring” could only fit the finger of a newborn. The discovery appropriately constitutes a final “joint effort” between the queen of Jerusalem archaeology, Eilat Mazar, and the dean of biblical archaeology, her beloved grandfather Benjamin. The ring is a tiny testament to nearly a century of Jerusalem archaeological work by the Mazars, uncovering the rich history of the Holy Land.

9. ‘Jabal’s’ Cattle Cult

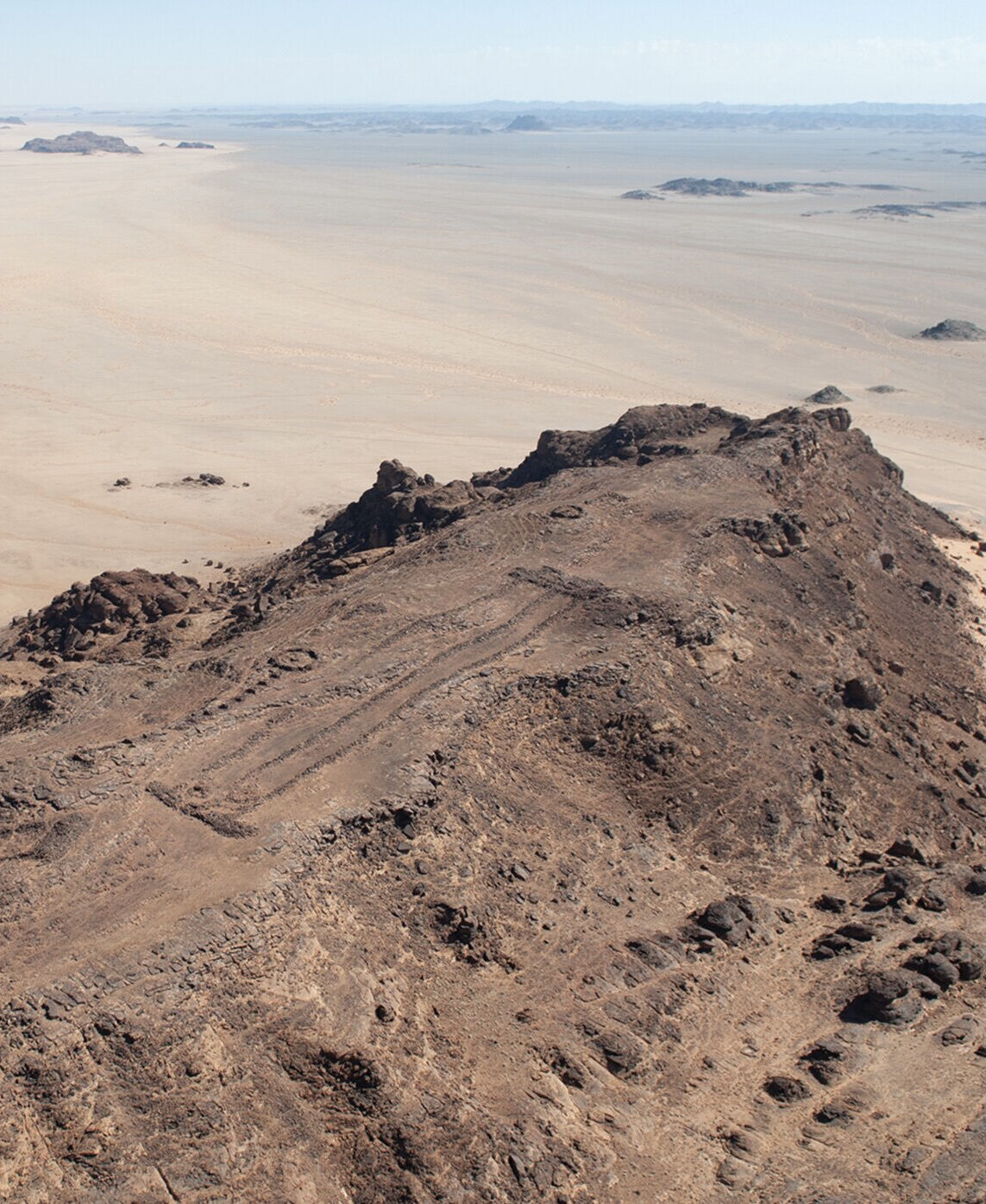

On April 30, a six-person team of researchers from the University of Western Australia published a research article in the journal Antiquity identifying monumental rectangular stone structures, or mustatils (Arabic for “rectangles”) scattered throughout northwest Arabia as part of a prehistoric cattle cult. This new research confirmed the suspicions of many scientists.

The stone structures, all of which were dated to the sixth millennium b.c.e., were characterized as the “first large-scale, monumental ritual landscape anywhere in the world [and] the earliest evidence for cattle cult in the Arabian Peninsula.” Along with cattle-related remains and rock art, evidence showed that the mustatils were more than merely cattle pens; they were also used in ritualistic activity.

This “monumental” discovery invokes a detail recorded in Genesis 4:19-20. In this passage, Jabal, son of Lamech (an individual sometimes associated with this Arabian region), is identified as “the father of such as dwell in tents [the Hebrew word can mean ritualistic chambers], and of such as have cattle” (King James Version). The italicized portion is not in the original Hebrew.

This passage has long been interpreted by Jewish commentators as the first biblical record of institutionalized idol worship (i.e. the fifth-century Genesis Rabbah, 23:3), with Jabal being the “first among men to erect temples to idols” (Legends of the Jews, 1.3.5); notably, such early worship in the context of cattle.

8. ‘Abrahamic’ Applied Geometry

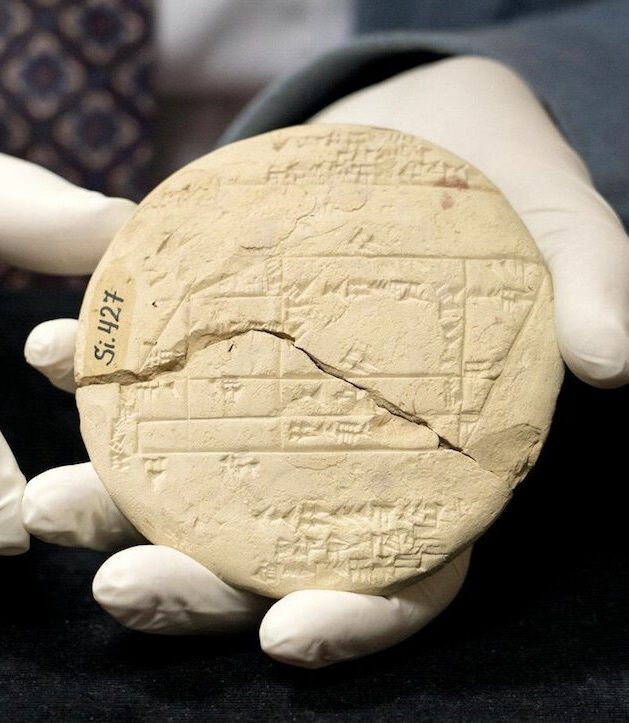

Nearly 130 years ago, scientists uncovered an intriguing mathematical artifact. However, its significance wasn’t fully understood until recently, thanks to the work of Dr. Daniel Mansfield, a mathematician from the University of New South Wales in Australia, who calls it “the oldest example of applied geometry in the world.”

The artifact, known as Si.427, is a circular tablet that dates to the Old Babylonian Period (1900–1600 b.c.e.). The face of the tablet depicts a land map divided into specific territories and boundaries. What is remarkable is that the tablet is not just a rough sketch, but an extremely accurate land survey.

Even more remarkably, Dr. Mansfield’s research shows that the map displays an understanding and application of the Pythagoras Theorem, often credited to the sixth century b.c.e. mathematician Pythagoras. In other words, Si.427 shows that the ancient Babylonians were using Pythagoras’s math theories more than 1,000 years before he was even born!

Dr. Mansfield’s findings mark a sensational development in our understanding of the history of mathematics. It also attests to the mathematical genius of ancient Babylon, and perhaps one especially influential mathematician and astronomer mentioned by the likes of early historians Berossus, Josephus, Eupolemus and Philo: Abraham!

Born and raised in ancient Babylon, both the Bible and ancient documents record that Abraham was a skilled mathematician and land surveyor. (Genesis 23:17-18)

Thanks to Si.427, we now know that the Babylonians during the time of Abraham did, in fact, possess an understanding of advanced mathematics, with a direct application to land surveying.

7. Armon Hanatziv Bog

A private toilet cubicle was discovered during recent excavations at Armon HaNatziv, a wealthy eighth-to-seventh-century b.c.e. promenade area overlooking the City of David. The toilet, made of carved limestone, is a comparatively rare discovery, as only the wealthy of the ancient world typically could afford such luxuries.

In addition to the seat and septic tank beneath (a veritable treasure trove for studying ancient diets), some 30 to 40 bowls were found within the cubicle area—items the excavators theorize may have held some type of air freshener, such as aromatic oils. Just outside the toilet cubicle, an ornamental garden was discovered as part of the mansion grounds, containing remains of fruit trees and aquatic plants.

The so-called Commissioner’s Palace fits with the biblical period of increasing wealth and opulence at the end of the reign of King Hezekiah, following Sennacherib’s failed siege (i.e. 2 Chronicles 32:27-29).

6. Jerusalem’s East Wall

In 2021, archaeologists working on the eastern slopes of the City of David uncovered a significant stretch of a First Temple period fortification wall that stood at the time of the Babylonian invasion in the sixth century b.c.e. This stretch of wall was preserved to a length of 40 meters and is 3 meters tall and 5 meters wide. Below the wall, a number of significant small finds were discovered, including administrative stamps.

Archaeologists are yet to secure a definitive date for the wall’s construction but believe that it was probably constructed around the late eighth and early seventh century b.c.e. This would fit neatly within the biblical account of King Hezekiah’s siege preparations and “strengthening” of Jerusalem’s wall in anticipation of an attack by King Sennacherib and the Assyrian army (2 Chronicles 32:5).

The discovery of this stretch of wall completes a much longer fortification line. Separate lengths of this city wall on either end, to the east and south of the city, had previously been uncovered. With the discovery of this in-between length of wall, Jerusalem’s overall southeastern fortification can now be seen to a full combined length of 200 meters.

5. Cave of Horrors Dead Sea Scroll

Within a cave located on the edge of a sheer cliff in the Dead Sea region (ominously called the “Cave of Horrors”), archaeologists uncovered a trove of 2,000-year-old items, including some 80 fragments of a Bible scroll containing preserved verses from the books of Nahum and Zechariah. In order to excavate the cave, archaeologists had to rappel 80 meters from the top of the cliff.

After examining the script, experts from the Israel Antiquities Authority Dead Sea Scrolls unit determined that it was the product of two different scribes. The texts were notable in that, while they were written in Greek, the names of God were written in the Hebrew language used during the First Temple period.

4. Solomonic Purple

Excavations at the ancient desert copper mines in Timna, southern Israel, may provide a glance into the wardrobes of King David and Solomon. Published in the January issue of the plos One journal, the discovery of fragments of 10th-century b.c.e. royal purple-dyed fabric was announced among the refuse of the ancient miners.

Royal purple, known as argaman in the Hebrew Bible, was a precious shellfish-derived dye mentioned several times in conjunction with the reign of Solomon—the color used most significantly for the temple. Roman records show that the dye was so valuable that it was worth as much as 10-20 times its weight in gold. This rare archaeological discovery (due to the fragile preservation of textiles) predates the oldest existing example of the dye by 1,000 years.

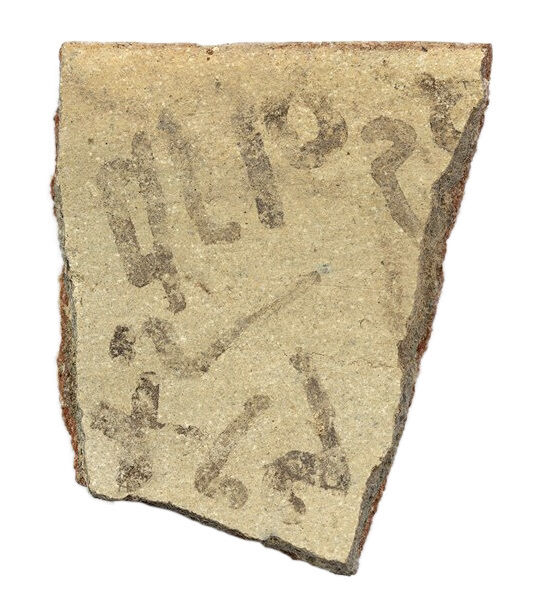

3. Alphabetic Script

In April, researchers from Austria and Israel announced the discovery of an inked potsherd inscription (ostracon), which constitutes, by a significant margin, the oldest alphabetic script discovered in Israel. Dating to the 15th century b.c.e., the fragment has been hailed as a “missing link” in the development of the alphabet. Previously, the earliest clear example of the script in the Levant dated to the 12th century b.c.e.

This discovery challenges the theories that the alphabet was brought into Canaan by the Egyptians during a later period of Egyptian dominance. It proves that the alphabetic script was present in Canaan some 200 years earlier than what certain scholars had proposed and that it can be witnessed at the time the Israelites arrived in the Promised Land, as per biblical chronology. (Ironically, the earliest forms of the alphabet, “proto-Siniatic”—predating its emergence in Canaan—have been found among a slave community in Egypt.)

2. Jerusalem’s Earthquake—and piglet?

In excavations on the eastern slope of the City of David, close to the Gihon Spring, archaeologists uncovered evidence of the catastrophic eighth-century b.c.e. event dubbed “Amos’s Earthquake.” The excavation unveiled a collapsed wall and displaced structures. Usually, damage of this magnitude is accompanied by a burn layer or the remains of weapons, both of which suggest destruction by conflict. In this case, there was no such evidence.

Written in the early-to-mid-eighth century b.c.e., the books of Isaiah and Amos warn of an earthquake befalling the land of Israel. The book of Amos begins with the postscript: “The words of Amos … two years before the earthquake.” The infamous quake is also documented in Zechariah 14:5.

Alongside the evidence of an earthquake, archaeologists found the remains of one of the casualties of this event—the articulated skeleton of a small piglet. Given that the piglet was located in a place where butchering evidently took place, it is clear the animal was intended for consumption. Bible critics point to the presence of a pig in Jerusalem as evidence against the existence of early biblical kosher laws.

In fact, the presence of a pig in Jerusalem during the mid-eighth century b.c.e. fits perfectly with the biblical record. For example, passages in Isaiah explicitly condemn the Jerusalemites for “eating swine’s flesh” (Isaiah 65:2, 4; 66:17). Instead of disputing the biblical account, this fascinating discovery verifies it.

1. Gideon/Jerubbaal Inscription

For the first time ever, archaeologists excavating in southern Israel uncovered an inscription bearing the name of a biblical-era judge. The 3,100-year-old inked pottery inscription bears the name of Jerubbaal, the lesser-known name for Gideon (Judges 7:1).

The pottery inscription was found in Khirbet al-Ra’i, in excavations led by Prof. Yosef Garfinkel and Saar Ganor. There is some debate as to whether or not this was the Jerubbaal of the biblical account. Some have noted the roughly 120-kilometer distance between the findspot and the famous battle between Gideon and Midian. However, there are several reasons to believe this is the Jerubbaal of the Bible.

First, the ostracon dates to the same time period (end of the 12th century b.c.e.). Second, Jerubbaal’s fame spread across all Israel (with pilgrimages from all Israel to his hometown). Third, Jerubbaal’s large family included 70 sons, who would have necessarily spread over a vast area. Fourth, the findspot of Khirbet al-Ra’i is linked to the Gideon account: Judges 6 shows that the Midianite oppression extended all the way to include this general territory on the Philistine border (verse 4). Fifth, the name Jerubbaal is rare, mentioned only in the Bible in connection to Gideon and found only on this potsherd dating to the same period. And finally, the meaning of the name, as explained in Judges 6, makes it one that would not necessarily be favorable to either a follower of God or Baal, thus explaining a rarity of use.

The evidence is tantalizing that this is the Gideon/Jerubbaal of the Bible. At the very minimum, the ostracon demonstrates the use of the name during this period.

Special Mention: Solomon’s Silver Trade

Dr. Sean Kingsley has been diving in Israel’s coastal waters since he was a teenager. In his quarterly magazine, Kingsley shared evidence from both underwater and above-ground excavations pointing toward the biblical maritime trade empire of King Solomon, and specifically the sourcing of “Solomon’s silver.”

The Bible records that, together with the Phoenicians, Israel’s 10th-century b.c.e. king presided over a vast commercial empire, one that included a network of mines, ports and ships, including a large port in Tarshish (1 Kings 10). Compiling a veritable mountain of discoveries, Dr. Kingsley identifies the Spanish city of Huelva, linked with the famous silver mine of antiquity (Rio Tinto, still in use today), as biblical Tarshish. (The name for the mine in 17th-century Spanish literature was “Cerro Solomon,” or the “Hill of Solomon.”)

Excavations at Huelva revealed massive Iron Age furnaces and sandstone molds for processing silver. Additional finds include an abundance of Phoenician pottery as well as murex snails, the source of the famous royal purple dye the Phoenicians were experts in processing, and which the Bible records Solomon importing. This incredible evidence has been dated to within the 10th century b.c.e. the period of King Solomon’s reign.