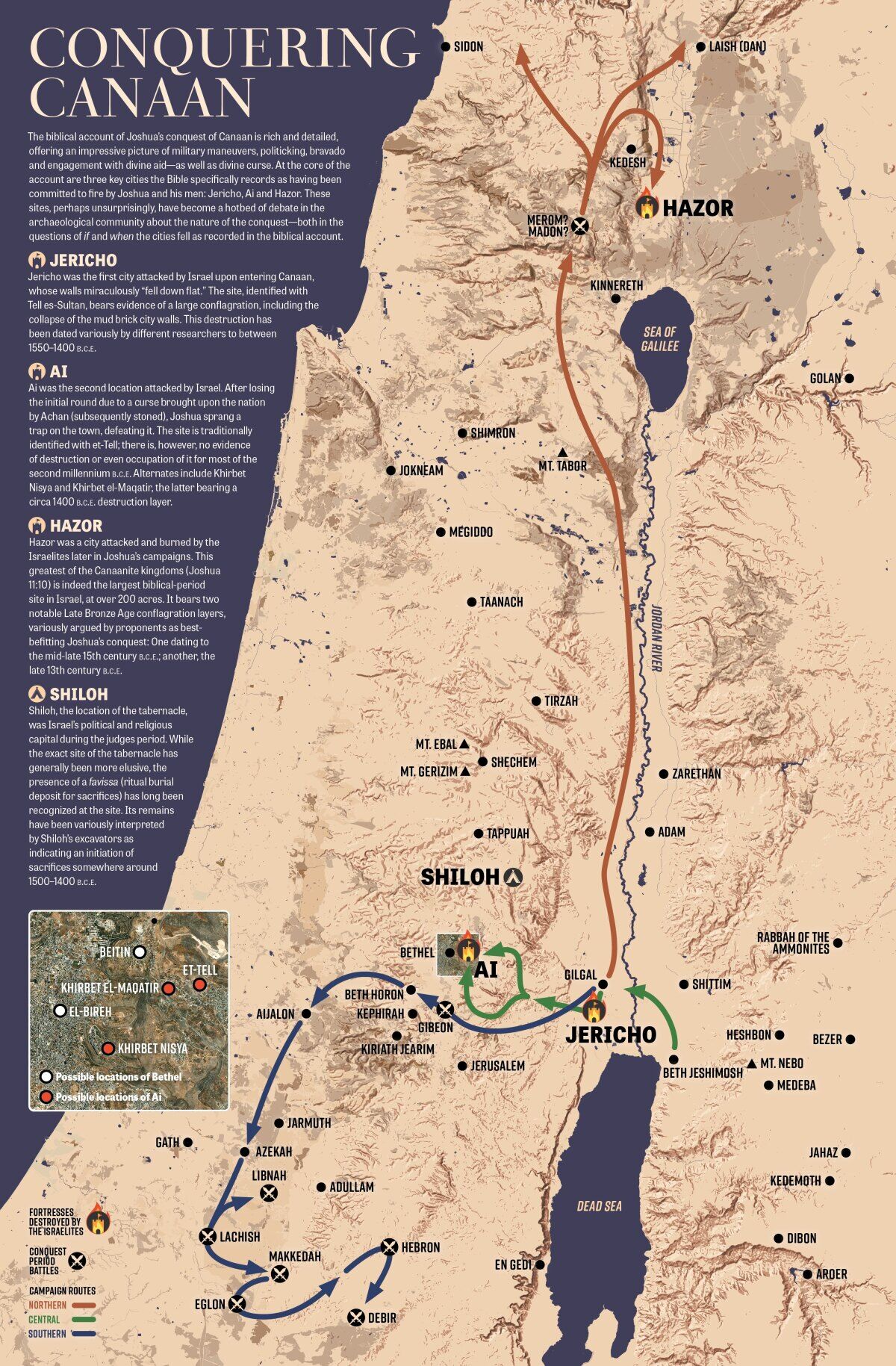

The biblical account of the conquest of Canaan graphically describes a path of utter destruction cut across the Promised Land by the Israelites, leaving in their wake a wasteland of cities in smoldering ruins. Right?

Wrong.

There are many assumptions and misconceptions about the biblical conquest of Canaan. One is the notion of the widespread annihilation and torching of cities. Actually, much of the conflict took the form of staged land battles—with many of the cities of Canaan being preserved. “[T]he Lord your God brings you into the land of which He swore … to give you large and beautiful cities which you did not build, houses full of all good things, which you did not fill” (Deuteronomy 6:10-11; New King James Version—see also Deuteronomy 20:16).

One of the most striking realities in the account of the conquest, therefore, is the lack of city conflagrations. But this doesn’t mean all of Canaan’s cities escaped incineration. The biblical text identifies three in particular that suffered a fiery demise—Jericho, Ai and Hazor. “And they burnt the city [Jericho] with fire, and all that was therein …” (Joshua 6:24). “So Joshua burnt Ai, and made it a heap …” (Joshua 8:28). “[A]nd he burnt Hazor with fire” (Joshua 11:11).

Joshua 11 emphasizes the lack of this type of destruction at other sites: “But as for the cities that stood on their mounds, Israel burned none of them, save Hazor only—that did Joshua burn” (verse 13). The Hebrew for “mound,” tel, refers specifically to an especially prominent, elevated city mound—as was the great Hazor.

These three cities have long been recognized as the key to unlocking the nature of the conquest account from an archaeological perspective. The presence of, and dating for, burned destruction layers at each site is crucial in determining both the accuracy of the biblical event and when it occurred.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, there is a maelstrom of debate and disagreement surrounding this subject. Within much of academia, the biblical conquest events are generally rejected as historical realities. Many believe they constitute late etiological legends for explaining the presence of ancient ruins in various locations.

For those who do hold to the historicity of the biblical conquest, there is even greater debate about when it took place. This is most prominently articulated in the “early vs. late” Exodus debate. The “early Exodus” view, which takes the biblical chronological information literally (such as 1 Kings 6:1 and Judges 11:26), typically places the Exodus in the mid-15th century b.c.e., with the conquest occurring 40 years later at the end of the century—around 1400 b.c.e., within the Late Bronze Age (specifically, the horizon between LB i and LB iia). The “late Exodus” view, which regards biblical chronological information more selectively and figuratively against a Ramesside Egyptian backdrop, typically places both events—the Exodus and conquest—somewhere within the 13th century b.c.e., with the conquest occurring around the end of the Late Bronze Age (LB iib).

When it comes to the subject of these three conquest-period cities, Jericho has long been the darling of the early-date community and Hazor, the late-date community. Meanwhile, Ai is the forgotten child, with some uncertainty surrounding its nature and location.

At the Armstrong Institute of Biblical Archaeology, the case has been made repeatedly and at length—following a literal reading of the biblical timeline—for the historicity of the early Exodus and conquest. But what about these three key conquest-period cities? Do they provide evidence for a unified conquest? And if so, to what period are they best ascribed? This article aims to answer these questions by considering the archaeological evidence from these three cities.

JERICHO

Ancient Jericho has long been identified with Tell es-Sultan. This site, situated 22 kilometers (14 miles) northeast of Jerusalem and 9 kilometers (5.5 miles) west of the southern end of the Jordan River, was one of the first sites in the Holy Land to be excavated. Jericho is famous in the biblical account as the city whose “walls came tumbling down” after the Israelites marched around it for seven days.

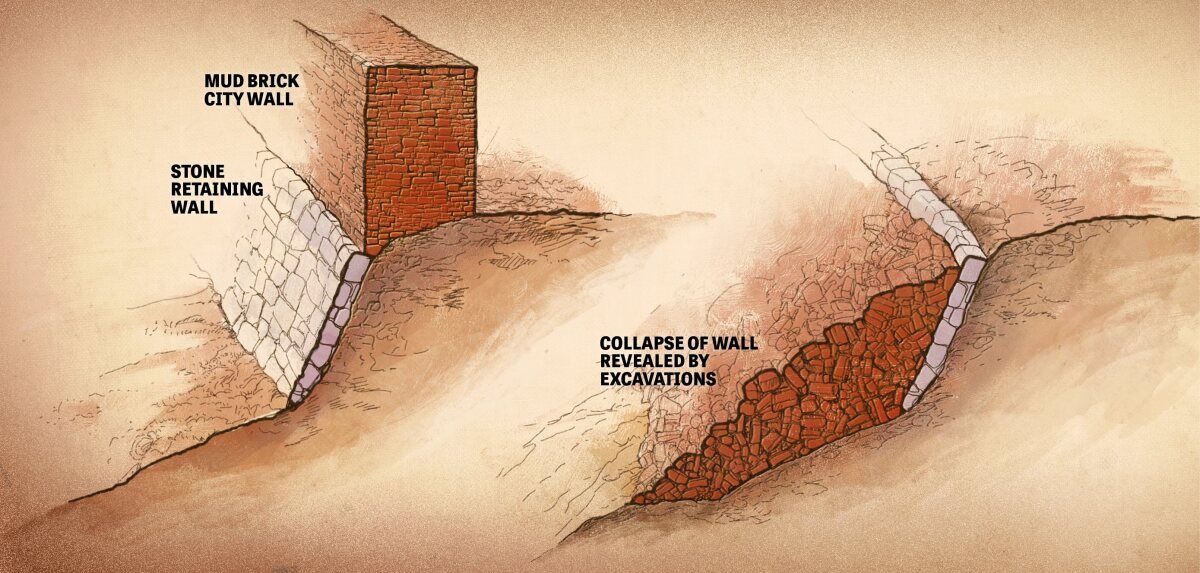

Archaeological excavation of the site has revealed a powerful early-mid-second millennium b.c.e. Bronze Age fortress. Named stratigraphically as “City iv,” the ruins are elevated on top of an approximately 5-meter-tall (16 feet) stone revetment, atop of which once stood a powerful mud brick city wall up to 4 meters (13 feet) tall. Notably, this mud brick wall was found to have collapsed flat, out and around the city—covered by a heavy layer of ash.

Garstang’s ‘Unmistakable Proof’

British archaeologist Prof. John Garstang (1876–1956) was one of the most prominent early excavators of Jericho, working at the site from 1930 to 1936. For him, the destruction of City iv, which he dated to circa 1400 b.c.e., constituted unequivocal evidence of the account described in Joshua.

To Garstang, the most notable feature was the nature of the collapsed city walls. Unlike in a normal conflagration, in which a besieged city’s walls would be breached inward, Jericho’s city wall had fallen outward, piling up against its lower stone-built terrace and forming an incline into the city. Not only did the picture of collapse accord with the biblical account of the fallen walls, the piling of bricks against the lower revetment would have allowed a sloped entry into the city for the assailants, also fitting the biblical account. “[T]he wall fell down flat, so that the people went up into the city, every man straight before him, and they took the city” (Joshua 6:20).

“What then could account for so stupendous a catastrophe?” Garstang wrote in The Story of Jericho (1940). No evidence of intentional undermining of the walls had been discovered, and the stone revetment supporting the mud brick fortress was still largely in place. “One conclusion indeed seems certain,” he concluded. “The power that could dislodge hundreds of tons of masonry in the way described must have been superhuman. Earthquake is the one and only known agent capable of the demonstration of force indicated by the observed facts …. [T]he evidence of the site itself, as revealed by our excavations, points incontestably to this solution.”

Yet this was not a destruction caused by an “earthquake” alone—for it coincided with the torching of the site. Striking was the discovery of significant quantities of incinerated wheat still contained within storage jars. This showed that the city did not endure a prolonged siege, which would have naturally diminished the food supply. Further, the remains pointed to the city’s destruction having occurred around spring harvest time—something explicitly described in the biblical account (e.g. Joshua 3:15; 5:10). Finally, one would have expected such precious food supplies to have been pillaged by its conquerors before the city was committed to fire. Yet in the case of Jericho, the Israelites were instructed not to take anything from the city for themselves (Joshua 6:17-19).

The linchpin, though, was the dating—based on pottery typology and scarabs. Garstang summarized: “Our excavations, logically interpreted, point to the fall of the city in the reign of Amenhotep iii (circa 1400 b.c.e.), possibly late in his reign (which is well represented), but before that of his successor Akhenaten, of whose period there is no trace—no royal signet, no influx of Early Mycenaean pottery, and no mention of Jericho in the Amarna letters. … [Jericho], according to biblical tradition, would fall about 1400 b.c.e. or just before, a result in very close agreement with that of our excavations” (“The Story of Jericho: Further Light on the Biblical Narrative,” 1941).

For Prof. Abraham S. Yahuda, Garstang’s discoveries settled the debate about the time frame of the Exodus and conquest. He wrote in his classic work The Accuracy of the Bible (1934): “[P]roof has quite recently come forth from the excavations of Jericho.” Based on biblical chronology, “the fall of Jericho must have taken place at about 1405 b.c.e., and this is exactly within the period assigned by Professor Garstang to the earthquake at Jericho. This fact can be taken as decisive. It is by itself the strongest evidence of the exactness of the Jericho story we could have ever expected; then it also confirms the biblical date of Joshua’s entry into Canaan.”

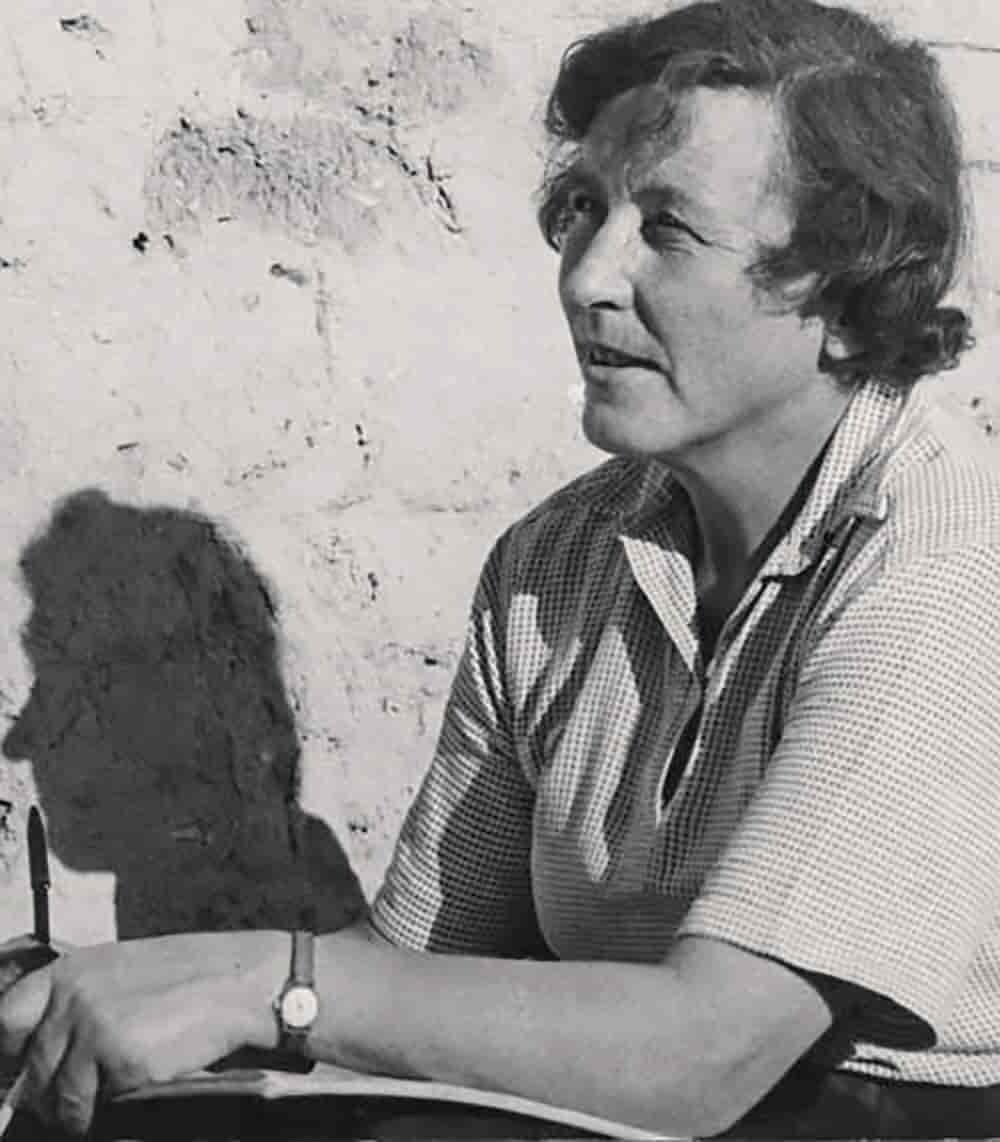

Then along came Kathleen Kenyon.

Kenyon: Not So Fast

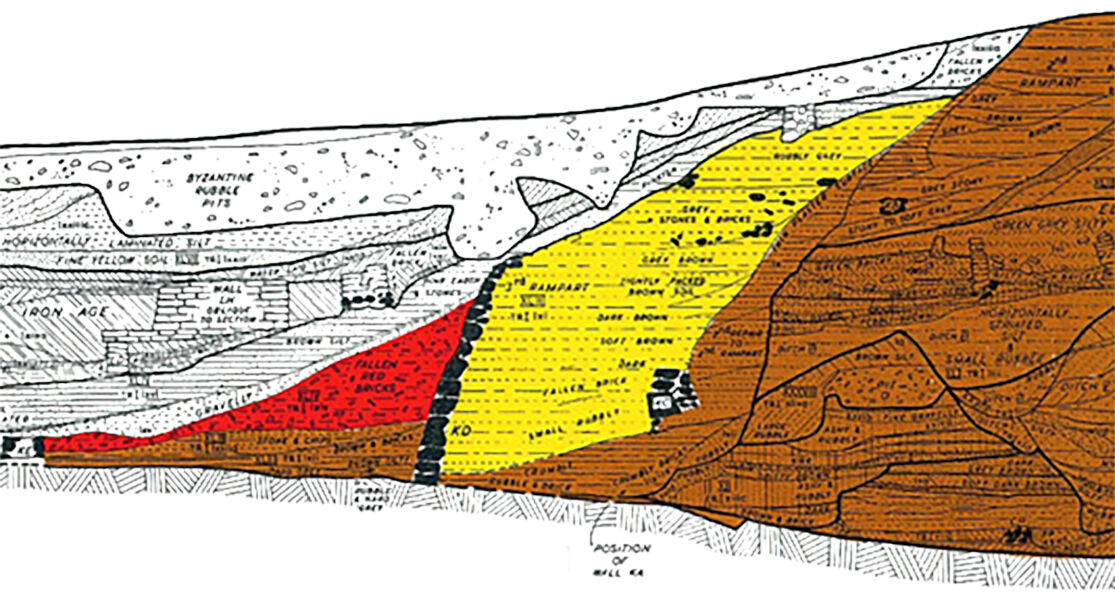

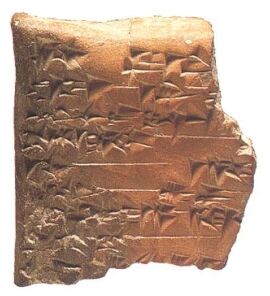

Dame Kathleen Kenyon (1906–1978) was an extremely influential and highly regarded British archaeologist, known especially for her excavations in the Holy Land—particularly in Jericho in the 1950s and in Jerusalem in the 1960s. She was instrumental in uncovering more of the same destruction remains discovered by earlier expeditions and dated by Garstang to the Late Bronze Age (note the cross section of her trench cutting, pictured above). She even described the “collapse of the walls” as “seem[ing] to have taken place before they were affected by the fire”—suggesting an earthquake just prior to burning (Excavations at Jericho, Vol. iii).

Kenyon, however, redated this destruction to the end of the Middle Bronze Age—circa 1550 b.c.e. This redating was based largely on the absence of Late Bronze Age pottery. As the last major excavator of the site (until the more recent Nigro excavations), and as an archaeologist renowned for her influential methods, Kenyon’s dating has stuck as the widely accepted conclusion for City iv. On the basis of her dating of the site, skeptics have long derided the biblical record—with a particular claim in circulation that not only did Jericho’s walls not come tumbling down for the Israelites, there were no city walls to fall down!

Is this the end of the story? Not quite. The foremost opponent to Kenyon’s redating of Jericho has been Dr. Bryant Wood, an expert in Late Bronze Age Canaanite pottery. Dr. Wood maintains that Garstang’s original dating of circa 1400 b.c.e. is correct.

Wood ‘Scores One for the Bible’

“I first became interested in Jericho while working on my Ph.D. dissertation on Canaanite pottery of the Late Bronze Age,” he wrote in a 1990 Biblical Archaeology Review article “Did the Israelites Conquer Jericho? A New Look at the Archaeological Evidence.” “I would occasionally thumb through Garstang’s preliminary reports to see if there was anything of interest. I became intrigued by a considerable amount of what appeared to be Late Bronze i (c. 1550–1400 b.c.e.) pottery he had excavated. This was precisely the period Kenyon repeatedly said was absent at Jericho …” (emphasis added throughout).

Unfortunately, no detailed report of Kenyon’s excavations was produced during her lifetime. Finally, in the early 1980s, two volumes on the pottery excavated by Kenyon were posthumously published, allowing for independent analysis.

“[I]t becomes clear that Kenyon based her opinion almost exclusively on the absence of pottery imported from Cyprus and common to the Late Bronze i period (c. 1550–1400 b.c.e.),” Wood wrote. “In other words, Kenyon’s analysis was based on what was not found at Jericho rather than what was found. … Dating habitation levels at Jericho on the absence of exotic imported wares—which were found primarily in tombs in large urban centers—is methodologically unsound and, indeed, unacceptable.”

Wood went on to highlight a number of items excavated by Kenyon, for which it is “obvious that these forms are from the Late Bronze i period and not the Middle Bronze Age.” He also drew attention to the continuous sequence of Egyptian scarabs that had been found in the northwest city cemetery, with scarab types spanning from the 18th century b.c.e. on through the reign of Amenhotep iii (late 15th to early 14th centuries b.c.e.). “The continuous nature of the scarab series suggests that the cemetery was in active use up to the end of the Late Bronze i period.” Finally, Wood highlighted a carbon 14 sample taken from the destruction layer which “dated to 1410 b.c.e., plus or minus 40 years.”

Wood’s reanalysis, articulated in a number of articles and videos, led to a resurgence of interest, including a feature in Time magazine titled “Score One for the Bible” (1990). “Other experts find little fault with Wood’s archaeology, but they are more skeptical about his linking of the evidence with biblical events,” the article concluded.

Carbon Conundrum

In the decades since, Wood’s conclusions have been contested, with a general academic consensus maintaining Kenyon’s dating. The aforementioned carbon sample was later determined to have been erroneously dated, and was redated to “1590 or 1527 +/- 110 b.c.e.” Additional tests done on further samples from the City iv destruction level returned dates broadly spanning a similar time frame—“between 1550 and 1520 cal. b.c.e.,” wrote Prof. Lorenzo Nigro (“Tell es-Sultan/Jericho in the Late Bronze Age,” 2023).

Still, Dr. Wood maintained his conclusions: “My dating of the destruction of Jericho to c. 1400 b.c.e. is based on pottery, which, in turn, is based on Egyptian chronology. Jericho is just one example of the discrepancy between historical and C14 dates for the second millennium b.c.e. C14 dates are consistently 100–150 years earlier than historical dates [for this mid-second millennium b.c.e. period]. There is a heated debate going on among scholars concerning this, especially with regard to the date of the eruption of Thera (Santorini). The literature on this subject is enormous …” (“Carbon 14 Dating at Jericho”).

Dr. Titus Kennedy summarizes the current status of C14 dating at Jericho in his 2023 article, “The Bronze Age Destruction of Jericho, Archaeology, and the Book of Joshua”: “Radiocarbon samples from Jericho have also been an important subject of discussion, but unfortunately, the radiocarbon dates from the Jericho iv destruction have been inconsistent ….

[A]nalysis of 18 samples from the Kenyon excavations at Jericho yielded results ranging from 3393 +/– 17 bp (GrN-18368) to 3312 +/– 14 bp (GrN-18539) … the calibrated probable dates given during the time of the study were 1601–1566 calbc or 1561–1524 calbc …. In 2000, the Italian-Palestinian expedition tested two samples that were excavated from a building that appeared to contain debris from the final destruction of the Bronze Age city that had washed down to the bottom of the mound. These two most recent samples yielded calibrated dates of 1347 bc +/– 85 and 1597 bc +/– 91, which could accommodate either proposed approximate historical destruction dates of around 1550 bc or 1400 bc if the calibration curves were accurate ….

However, it is a known issue that the radiocarbon dates for Bronze Age sites in the Levant often conflict with the chronological information derived from ceramics and inscriptions and that some samples can be from burned wooden beams cut from trees that were harvested over 100 years before their destruction …. Thus, radiocarbon dates should be viewed with caution, and dating strata by means of pottery typology continues to be the primary and most reliable method employed by archaeologists.

While a few radiocarbon samples from Jericho do fit a Late Bronze ib destruction of the city around 1400 bc, others match more closely to a 1600–1500 bc destruction timeframe. Essentially, the radiocarbon dates from Jericho at present appear to only rule out a ca. 1230 bc destruction hypothesis but have not been able to solve the dispute between a Middle Bronze iii or Late Bronze i destruction of the city.

Nigro to Now

Following Kenyon, Jericho’s most recent excavations have been accomplished by a joint Italian-Palestinian team led by Prof. Lorenzo Nigro. Nigro generally maintains Kenyon’s date for the destruction of Jericho and roundly rejects the historicity of the biblical account. Still, he grants that the biblical description of Jericho’s fall might have at least been influenced by the destruction of City iv (“The Italian-Palestinian Expedition to Tell es-Sultan, Ancient Jericho [1997–2015],” 2020).

For those looking for a historical conquest, the evidence from Jericho has resulted in a number of differing opinions. Some have proposed earlier schemes, putting both the Exodus and Joshua’s conquest in the 16th century b.c.e., in concert with Kenyon’s dating of City iv. Certain chronological revisionists—such as David Rohl—at least generally accept Kenyon’s stratigraphical analysis in associating the destruction with the latter Middle Bronze period, but believe the entire chronology of this period for the ancient Near East should be down-dated by up to several centuries (including for all other sites and associated strata). Still others are in the less-extreme camp of Wood, believing the chronology of the Near East to be broadly correct, yet believing Jericho’s City iv to have been wrongly dated between 100 and 150 years too early. These differing interpretations are at least unified in recognizing Jericho’s City iv as best befitting the city and its destruction described in the Joshua account. Even those who do not regard the biblical account as reliable or historical—such as Kenyon and Nigro—point to the demise of this phase of the city as at least potentially being alluded to in the biblical account.

[Note, 21/1/26: In the months since the publication of this article, early Exodus proponent Bryan Windle (Associates for Biblical Research) has been on the circuit making the case for Jericho’s later City v as best befitting the account of Joshua’s destruction—highlighting new interpretations of data relating to remains otherwise associated with City iv (particularly the mud brick collapse). This new theory is most notably articulated in his December 30, 2025 publication Joshua’s Jericho: The Latest Archaeological Evidence for the Conquest. This is an interesting development, and while I am not yet convinced, it nevertheless will be interesting to see how this new interpretation holds up over time.]

Finally, there is the late date (13th century) position, which—though there is no evidence of broad site destruction during this time—holds to Nigro’s assessment that Jericho’s “LB iib layers were heavily cut by leveling operations carried out in the Iron Age … explain[ing] the scarcity of 13th-century materials.” Thus, the potential that remains from this period may have simply been cleared away. Still, Nigro points to Jericho as having been but a “smaller town” at this time, “laying on top of the ruins of the previous large city [iv]” (op cit).

This is where the current dialogue sits regarding Jericho. And so on we march—to Ai.

AI

Following the conquest of Jericho, the next city to be advanced upon by the Israelites was Ai—a name generally held to mean “the ruin.” This second location encountered by the Israelites was one in which their forces suffered a surprise defeat before it was discovered that a curse had been brought upon them by Achan, who had taken forbidden treasure from Jericho. Following his execution, Joshua led an ambush on Ai, successfully capturing and destroying the city.

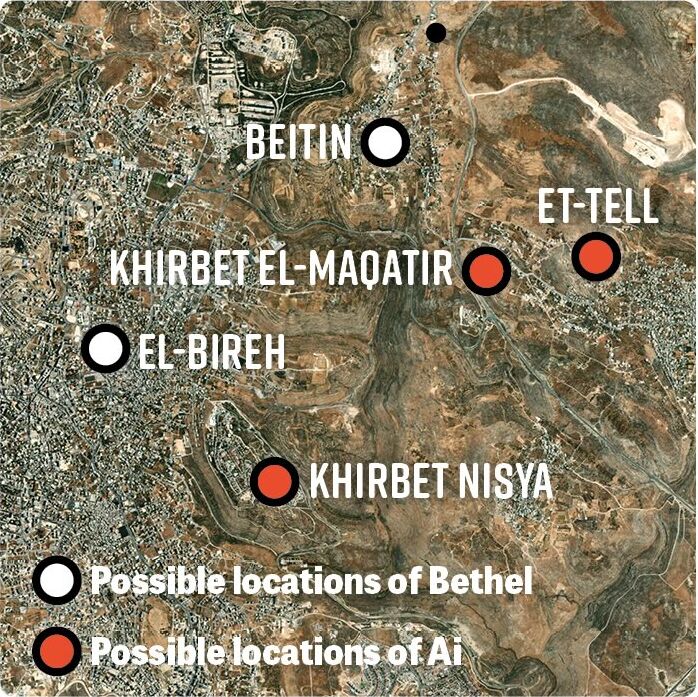

Ai was identified early on with the imposing site of et-Tell (an Arabic name also meaning “the ruin”). The identification of Ai is based on a number of topographical indicators—including its location adjacent east of Bethel (per Joshua 7:2; a site identified with either the nearby Beitin or el-Bireh). The identification of et-Tell as Ai was backed by a number of early archaeology and geography heavyweights, including Edward Robinson, Charles Wilson and William Albright.

Yet when the site began to be excavated—especially in the 1930s and throughout the 1960s-70s—there was a problem. The site belonged in the Early Bronze to early Middle Bronze time period. The city functioned and was destroyed at the end of the third millennium b.c.e., with no ensuing occupation during nearly all of the second millennium b.c.e. Et-Tell finally began to be resettled from the early 12th century b.c.e. onward—yet the evidence showed this to have been a peaceful resettlement with no sign of destruction. Not only was there no sign of destruction in the city during either of the proposed “early” or “late” schemes, there was no sign of occupation!

Naturally, this posed no issue for those holding to the position that the conquest accounts were mere etiological legend. But for Dr. David Livingston (1925–2013), founder of Associates for Biblical Research (abr), this was not good enough.

Livingston’s Nisya

The problem with et-Tell was not just with the dating of occupation and the lack of destruction. There were additional, fundamental red flags in identifying Joshua’s Ai with et-Tell.

Chief among them was its size. Et-Tell is a large site, covering 27 acres—triple the size of Jericho. Yet the biblical account takes pains to describe Ai as comparatively small. Joshua 10:2, for example, states that ancient Gibeon was “larger than Ai” (New International Version; many other translations render the term גדולה as “greater,” though the same sense is given). Though the exact extent of Gibeon during the Late Bronze Age remains unknown, the known size of its Iron Age city is roughly half that of et-Tell, at about 15 acres (and it stands to reason that Gibeon’s Iron Age fortification was built atop the earlier Middle Bronze Age wall). Additionally, Joshua’s spies noted the small population of Ai, recommending Joshua send only a small division of soldiers, “for they are but few” (Joshua 7:3). These scriptures, at face value, logically infer a much smaller site.

Livingston wondered if the true location of Joshua’s Ai might be better found at Khirbet Nisya, a small site situated 4 kilometers southwest of et-Tell. Livingston put his theory to the test and began what would ultimately be six seasons of excavation at the site during the late-’70s to mid-’80s. His excavations revealed remains from the relevant Late Bronze Age, but they constituted only a village, with no evidence of fortification. “Khirbet Nisya seems to have been an agricultural village or hamlet in most periods,” wrote Livingston. “Although, on the basis of the evidence from six seasons of excavation, no claim can be made that it is Ai, it does not seem necessary yet to rule it out, either” (“Khirbet Nisya 1979-1986: A Report on Six Seasons of Excavation”).

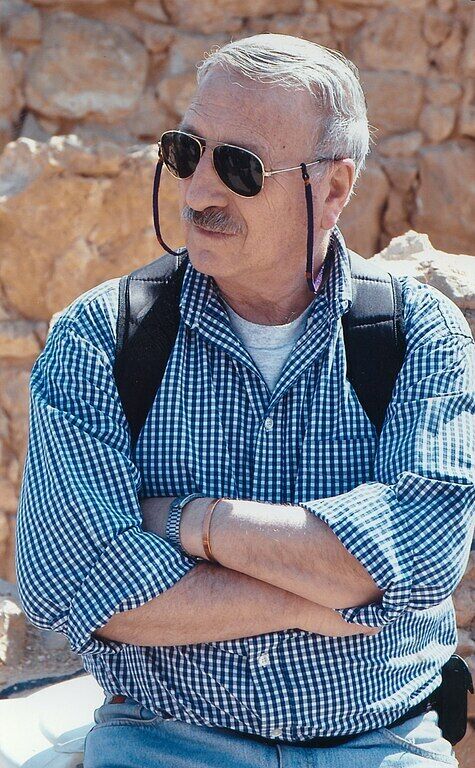

Livingston’s findings were not enough for the aforementioned Dr. Bryant Wood (who would go on to follow Livingston as a director of abr). Wood had his eye elsewhere—a small site barely 1 kilometer west of et-Tell: Khirbet el-Maqatir.

Wood’s el-Maqatir

Beginning in 1995, Wood began excavations at el-Maqatir. This became a key site for the abr team, which would go on to complete 14 seasons there (from 1995–2001 and 2009–2016; the 2014–2016 seasons were directed by Dr. Scott Stripling).

The site conforms with a number of key parameters for Joshua’s Ai, including in its diminutive size—just under 3 acres (about a third the size of Jericho). Geographically, it is located east of Bethel (as either Beitin or el-Bireh; Joshua 7:2). It is fronted to the north by the highest hill in the region, befitting the northern location in which Joshua placed the main part of his army (Joshua 8:11). Between the northern hill and el-Maqatir is a shallow valley, fitting with the location in which Joshua descended overnight (verse 13). On the west side of el-Maqatir is a deep valley within which an ambush force could hide, obscured from the view of the city (verse 12).

“Another requirement would be that it would have line-of-sight communication with Jerusalem,” Wood stated (interview, “Digging Up Joshua’s Ai at Khirbet el-Maqatir”). “Ai was the northern border fortress for Jerusalem and the southern city-states. And we have that as well. We have a very clear view of Jerusalem, about 10 or so miles to the south” (something possibly hinted at in Joshua 10).

More striking than the geographical parallels were the archaeological. Despite its small size, Khirbet el-Maqatir was fortified by a city wall. It was also operational during the Late Bronze i period. Evidence of a gatehouse was discovered on the city’s north side—remarkably paralleling Joshua 8:11’s reference to the “front of Ai” as “to the north” (Berean Study Bible). Significant finds from within the city included a scarab dating to the reign of Amenhotep ii (mid-late 15th century b.c.e.), as well as a ritual Canaanite infant jar burial. The presence of this infant burial is itself significant, as it demonstrates the presence of women at the small fortified site, as attested in the biblical account (“all that fell that day, both of men and women,” Joshua 8:25).

Finally, evidence was found at the site of destruction by fire and subsequent abandonment—dated to circa 1400 b.c.e. “Abundant evidence for destruction by fire has been found at Khirbet el-Maqatir in the form of ash, refired pottery, burned building stones and calcined bedrock,” wrote Michael Grisanti (“Recent Archaeological Discoveries That Lend Credence to the Historicity of the Scriptures,” 2013).

In the opinion of Wood, the collective evidence for Khirbet el-Maqatir as Joshua’s Ai is much stronger than that of et-Tell. “[E]t-Tell miserably fails as a candidate for Joshua’s ‘Ai since it has no Late Bronze Age occupation, no militarily significant hill or shallow valley to the north, and lacks an ambush site that would provide cover from both ‘Ai and Bethel. Since it was unoccupied in the Late Bronze period, it does not meet any of the numerous archaeological requirements for ‘Ai. What is more, et-Tell is without an ancient local tradition linking it with ‘Ai” (Wood, “Locating ‘Ai: Excavations at Kh. el-Maqatir 1995–2000 and 2009–2014,” 2016).

Regarding such local traditions, Wood draws attention to the accounts of early explorers visiting his site. “When [Edward] Robinson visited Kh. el-Maqatir on May 5, 1838, he was told by Greek priests and inhabitants of nearby Taiyiba that it was the location of ‘Ai.” Robinson ultimately dismissed their identification, preferring to locate Ai elsewhere. Nevertheless, just the same, “[s]ixty-one years later, when Ernest Sellin visited the site [of el-Maqatir] in 1899, locals identified it as ‘Khirbet Ai.’”

Wood concludes that collectively, the “evidence from archaeology, topography and local tradition clearly points to Kh. el-Maqatir as being the best candidate for the ‘Ai of Joshua 7–8. Mathematically, the identification is highly likely” (ibid).

Unfortunately—perhaps given the diminutive nature of Khirbet el-Maqatir, but perhaps also due to its more recent identification, excavation and publication—the site has received comparatively little attention. Meanwhile, others who still favor identifying the site of et-Tell as Ai wonder if there was a population that somehow “lived among the ruins” of the earlier city, who “experienced a sort of scaled-down conquest” (as posited by 13th-century proponent Dr. Ralph K. Hawkins in How Israel Became a People), the evidence of which might have been missed by excavators. In the words of late-date proponent Prof. Kenneth Kitchen: “It still needs to be remembered, also, that the entire area of et-Tell has not been dug; fully eroded parts, of course, can never tell us anything now” (On the Reliability of the Old Testament).

With this as the status quo for Ai, on we march—far to the north—to our final destination: Hazor. (See the following article for commentary on recent developments concerning the question of Ai’s identification with et-Tell, as articulated in a recent video by the popular YouTube channel Expedition Bible.)

HAZOR

Unlike Ai, the Bible states that Hazor was a massive site. “At that time Hazor was the most powerful of all those kingdoms” (Joshua 11:10; Good News Translation). Fittingly, Hazor is the largest biblical-period site in Israel, with an upper tel that spans roughly 30 acres and a sprawling lower city covering more than 175. This northern city (situated about 14 kilometers north of the Sea of Galilee) reached its zenith during the Middle to Late Bronze Age.

Yet it came to a grinding halt in the 13th century b.c.e., at which time it suffered a catastrophic destruction.

Yadin, Ben-Tor: Joshua Did It

This destruction was uncovered during the 1950s excavations of Hazor by Prof. Yigael Yadin and Prof. Yohanan Aharoni. The site was later excavated by Yadin’s protégé Prof. Amnon Ben-Tor, who noted the destruction of Stratum xiii (upper city) and Stratum 1a (lower city) as “no earlier than the middle of the 13th century b.c.e.”

“Hazor was not destroyed by an accidental fire, an earthquake or any other natural catastrophe,” the late Ben-Tor wrote in a 2013 Biblical Archaeology Review article. “The destruction was clearly the result of human activity, as indicated by the large number of statues of deities and rulers that were intentionally disfigured by cutting off their heads and hands. Since we have no record mentioning the destruction other than the book of Joshua, the only way to go about answering the question of who destroyed Hazor is to consider all those peoples who were around at the time, examining whether any of them can be regarded as a possible candidate for the city’s destroyer” (“Who Destroyed Canaanite Hazor?”).

In his article, Ben-Tor examined whether the city could have been destroyed by Ramesses ii, the Sea Peoples, other Canaanite city-states or enemies from within. He ultimately concluded that the biblical account of Joshua’s conquest best befits the evidence—particularly with the notable change in settlement pattern at Hazor following this destruction, paralleling Israelite settlement at other sites.

Unsurprisingly, the 13th-century b.c.e. destruction of Hazor has, therefore, long stood as one of the chiefest and most impressive “proofs” for the late-date Exodus and conquest of Canaan (or, at least for those disagreeing with the historicity of the Exodus and conquest, the general period of the formation of Israelite statehood).

Case closed? Hardly!

Petrovich: Not the Only Destruction

There is no question that Hazor was destroyed in the 13th century b.c.e. But as highlighted especially by Prof. Douglas Petrovich, this is not the only Late Bronze Age destruction of the city. There is, in fact, another—one that dates to the 15th century b.c.e.

This destruction is represented in Stratum xv of the upper city, and Stratum 2 of the lower. “As for what is known of the demise of the Late Bronze i city, the opinion of most is that its destruction, visible both atop the tel and especially in the lower city, occurred sometime from c. 1455–1400 b.c.e.,” wrote Petrovich. “Yadin notes accordingly ‘that the temple of Stratum 2 was destroyed by an enemy and the people abandoned it abruptly.’ The destruction of Jericho’s City iv (Late Bronze i Age), which stratum is contemporaneous with Hazor’s Stratum 2 of the lower city, reveals a similar appearance of abrupt abandonment. … [Notable is] Ben-Tor’s comparison of the fiery destruction of the Late Bronze i city to that of the Late Bronze iib/iii city ….”

According to Petrovich, this shows that the former LB i city “clearly was destroyed by a massive conflagration as well. … Various sections of the burn line and residual burned areas, which measure half a meter in some places, have been preserved …. This burn line, visible throughout the excavated area, reveals the unmistakable signs of a great conflagration” (“The Dating of Hazor’s Destruction in Joshua 11,” 2008).

In the words of Ben-Tor himself: “This earlier [LB i] phase ended in a conflagration, similar to the one that brought the later [LB iib] phase to an end. The ceramic assemblage associated with this earlier phase, albeit meagre, seems to place the date of this earlier destruction somewhere in the Late Bronze Age i (fifteenth century b.c.e.). This destruction is most probably contemporary with the end of Stratum 2 in the lower city …” (“Excavations and Surveys: Tel Hazor, 2001”).

Yadin writes of this level: “This Stratum 2, representing the sixteenth-fifteenth centuries in Hazor, emerges as one of great prosperity and cultural standards. This is no doubt the Hazor of the Thutmosis iii period.” He goes on to describe the demise of the “LB i Temple—Stratum 2”: “The final destruction of the temple is represented by a thick layer (0.7 m.) of brick debris. … Similar debris was uncovered on the floors of the lb i Temple in Area A” (Hazor, the Head of All Those Kingdoms: The Schweich Lectures of the British Academy, 1972). This destroyed structure was then replaced in Stratum 1b with “a completely new building, built on the ruins of the temple of Stratum 2.”

On this basis, the late 15th-century b.c.e. destruction is typically attributed by early-date proponents to Joshua. But what of the widespread 13th-century b.c.e. destruction? Again, in the words of Ben-Tor, there is “no record mentioning the destruction [of Late Bronze Hazor] other than the book of Joshua.”

That’s true—sort of.

From Joshua to Judges

Interestingly, the city of Hazor does continue to feature prominently in the ensuing biblical account—and not as an Israelite city, but as a Canaanite one.

During the Judges period, Hazor became the seat of one of Israel’s greatest oppressors. “… Jabin king of Canaan, that reigned in Hazor … mightily oppressed the children of Israel” (Judges 4:2-3). Judges 4 records the miraculous defeat of Jabin’s captain Sisera and his massive force of 900 chariots. And while there is no explicit mention of Hazor itself in the ensuing account, it does conclude with the following: “So God subdued on that day Jabin the king of Canaan before the children of Israel. And the hand of the children of Israel prevailed more and more against Jabin the king of Canaan, until they had destroyed Jabin king of Canaan” (verses 23-24).

Following Sisera’s defeat, in order to go on “more and more” to finally “destroy” the Canaanite Jabin, this certainly must have required a final assault on the very stronghold of the king: Hazor.

Only then—following this mid-Judges period overthrow of Canaanite control at Hazor, which in early-date schemes naturally falls within the 13th century b.c.e.—would the city be inhabited by Israelites, as represented in the continuing archaeological record. (Read more about this particular judges-period episode here.)

Intriguingly, even Dr. Richard Elliott Friedman—who favors a scaled-down 13th century Exodus model—submits for reasons of his own that this Stratum xiii/1a “destruction layer [which] is at the site of the city of Hazor … fits better with the account of Deborah’s defeat of the king of Hazor” (The Exodus: How it Happened and Why it Matters).

The Sum Total

The present discourse on these three key conquest-period cities—Jericho, Ai and Hazor—is, admittedly, a mess. Yet out of the haze of debates, dates, destructions and disagreements, it seems to me that quantitatively, for a unified campaign, there is one clear option—the early-date conquest—with a circa 1400 b.c.e. destruction of Jericho City iv (on the basis of Garstang’s original dating and Wood’s reanalysis), the identification of Khirbet el-Maqatir as Ai, and identifying Joshua’s destruction with Hazor’s earlier Stratum xv/2.

Ironically, I find some of the strongest evidence for this early-date conquest to be from that mighty flagship of the late-date community: Hazor. As articulated in a simple question posed by a viewer of late-date proponent Dr. David Falk’s channel: “Since Hazor was destroyed (13th century b.c.e.) … where did Jabin rule from? (Judges 4:2).” There have been varying attempts to reconcile the nature of the Hazor of Judges 4 in relation to the Hazor of Joshua 11. Prof. Benjamin Mazar even argued that the Judges 4 event predated the Joshua 11 event (although for different reasons). Yet a straightforward reading of Judges 4 implies an ongoing (or reestablished) Canaanite presence at Hazor following an initial destruction (of Stratum xv/2), before a final, later judges-period destruction (of Stratum xiii/1a) finally broke the back of Canaanite domination from the city.

To the same end, ultimately, I find late-date appeals to silence with regards to Jericho and Ai weak. And when it comes to Jericho, dating specifics aside, perhaps no biblical event is more aptly and vividly illustrated archaeologically than the demise of City iv.

This, then, is where we are at—91 years on from Professor Yahuda’s declaration of the debate as “over.” Barring nothing short of a wall-felling miracle, the debate on the nature of Joshua’s conquest is sure to continue—perhaps leaving the reader to commiserate with the great commander Joshua’s final words: “I am old and well stricken in years” (Joshua 23:2).

Read More:

Shiloh Sacrifices: Canaanite Or Israelite?

Et-Tell: Joshua’s Ai After All?

Article updated 21/1/26.