Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Beth Shemesh

A beautiful landscape connects Israel’s Coastal Plain to the Shephelah (Judean foothills) west of Jerusalem. Cutting through the Shephelah are pleasant valleys filled with fertile farmlands. These valleys, however, were places of war and turmoil throughout several biblical epochs. In the Sorek Valley of Israel lies a city whose biblical history has been laden with strife: Beth Shemesh. Beth Shemesh is a focal city in several Bible stories, including the story of Samson, the return of the ark of the covenant to Israel, and a major clash between King Amaziah of Judah and King Joash of Israel.

The site of Tel Beth Shemesh—just across Highway 38, west of the modern city Beit Shemesh—is open for visitors, but an understanding of the site’s story and archaeology takes some study.

Canaanite Origins

Beth Shemesh began as a Canaanite city. A few extra-biblical sources and the earliest remains at the site (as well as its name) highlight its early Canaanite nature, as attested in the Bible.

“Beth Shemesh” is a curious name for an Israelite city. Shemesh in Hebrew (שֶׁמֶשׁ) means “sun” (thus “House of the Sun”), but archaeologists believe the name of this city likely carries a different sense. Prof. Noam Agmon, in an article titled “Tatami: The Enigmatic Toponym of Western Judah,” notes that Beth Shemesh “centered at some period around the worship of the Canaanite sun-deity Šapash/Šhamash.” Shemesh was the Canaanite goddess of the sun—a prominent deity. Shemesh is referenced in famous Mesopotamian texts, including the Code of Hammurabi and the Epic of Gilgamesh. Worship of Shemesh in the region probably centered around Beth Shemesh, as evidenced by a Canaanite temple discovered within the city.

The Egyptian “execration texts” are curse rituals which involved writing curses for places, civilizations or individuals on objects (figurines or pieces of pottery) and then smashing the objects to pieces. Georges Posener, who discovered a large group of these tablets in the 1920s, identified Beth Shemesh in tablet E 60. Archaeologist William F. Albright agreed that Beth Shemesh was among these “cursed” cities. Professor Agmon wrote: “This identification, if correct, allows one to date Beth Shemesh. Because ‘asinnu (Beth-Shemesh) appears on the Berlin bowls it should predate mb ii (before 1850 b.c.e.).”

None of the famous 14th-century b.c.e. Amarna letters mention Beth Shemesh by name. (These famous texts were written by Canaanite leaders pleading with the Egyptian pharaoh for help against an invading Habiru people—read more about the Habiru identity in “What is the Correct Time Frame for the Exodus and Conquest of the Promised Land?”) However, archaeologists suggest that letters EA 273-274 were written from Beth Shemesh. Prof. Nadav Na’aman wrote that Beth Shemesh was the most likely candidate because it was the most prominent Canaanite city in the eastern Shephelah, aside from Gezer, which had letters of its own (“The Shephelah According to the Amarna Letters”).

American Bible scholar Edward Robinson identified the site of biblical Beth Shemesh in 1856. His identification was based on geographical descriptions provided in the Bible, the Onomasticon by the third-century c.e. historian Eusebius, and the Arabic name of a tiny village called “Ain Shems.” Excavations commenced at the site in 1911 under the direction of Scottish archaeologist Duncan Mackenzie, which made Beth Shemesh one of the first sites in the then Ottoman-controlled region to be excavated. Mackenzie unearthed large portions of the city’s fortifications, including the Strong Wall and the South Gate, whose foundations he dated to the Bronze Age.

Subsequent excavations were performed from 1928 to 1930 under American archaeologist Elihu Grant. Grant excavated the western half of the mound and proffered a date in the late 17th to early 16th century b.c.e. for its Canaanite fortifications. Grant and archaeologist G. Ernest Wright made many small finds and exhumed the ruins of a temple structure: The temple faced west (toward the setting sun) and contained many miniature cultic objects. Nearby, an offering stone was discovered, along with a discovery of a well-preserved Anath-figurine carving (Beth-Shemesh, 1928 by Elihu Grant). These discoveries show Beth Shemesh’s early cultic importance. Archaeologists Shlomo Bunimovitz and Zvi Lederman have been excavating the site since 1990, and they have made many more Canaanite-era discoveries.

Archaeology has shown that Beth Shemesh was a fortified city and cultic center by the time the Israelites entered Canaan. Its south gate was an immense entrance situated between two substantial defensive towers. Uncharacteristically of Canaanite fortresses, Beth Shemesh’s fortifications did not include a glacis, or an earthen embankment intended to stymie siege weaponry. The lack of a glacis and the Amarna letters seemingly authored from Beth Shemesh by an independent ruler indicate that it was an autonomous city, at least in the late Canaanite period.

Judges Period: Israelite, Canaanite, or Philistine?

There is a level of debate about who occupied Beth Shemesh in the judges period. Bunimovitz and Lederman, in a piece titled “A Border Case: Beth-Shemesh and the Rise of Ancient Israel,” wrote about Beth Shemesh in the Iron Age judges period: “At Beth-Shemesh we are facing a most intriguing situation. The strong Canaanite cultural traditions during most of the period seem to suggest that it was a Canaanite town. This is certainly at odds with the ethnic reality at the Sorek Valley portrayed by the biblical accounts about the pre-monarchic period.” Is there really a conflict between the archaeology of the site and the biblical account?

The Bible clearly indicates that Beth Shemesh was occupied by Israelites during the judges period. The story of the Philistines returning the ark in 1 Samuel 6, for instance, would make no sense if Canaanites lived in Beth Shemesh. Some archaeological features also attest to an Israelite populace. (No sign of pork consumption, for example, has been discovered in Beth Shemesh during this period—and the lack thereof is a readily identifiable trait among Israelite-inhabited cities.)

Bunimovitz and Lederman support their position that Beth Shemesh remained Canaanite by highlighting two pieces of evidence. First, “[a]rchitecturally, there is a remarkable cultural continuity between the Late Bronze and the Iron Age i levels” (“Canaanite Resistance: The Philistines and Beth-Shemesh—A Case Study from Iron Age i”). Second, they refer to plaques from the period inscribed with theophoric names including “Baal.”

Neither point bars the city from having been occupied by Israelites. Deuteronomy 6:10-11 and 19:1 are commands for the Israelites to live in the Canaanite homes and cities. Therefore, the Bible shows that archaeologists should expect nothing but architectural continuity between the Canaanites and Israelites.

Israelite theophoric names including “Baal” are also not contrary to the Biblical narrative. There are numerous examples of Israelites engaging in Canaanite religion in the period of the judges—including Baal worship (Judges 2:13; 6:25-30; 8:27; 9:4, 45-46; 10:6-10; 13:1; 17:1-13; 18:4-31; 1 Samuel 7:3-4). For more about “Baal” being in Israelite names, read our article, “Shaming the Name (Quite Literally): From ‘Baal’ to ‘Bosheth.’” The presence of such Canaanite practices during this period at Beth Shemesh validates the biblical account of Israelite behavior during the judges period.

Biblically, there was one other major influence over Israel during this time: the Philistines.

Between Ekron (one of the cities of the Philistine pentapolis) and Beth Shemesh were only 12 miles of spacious and flat Sorek Valley farmlands. G. Ernest Wright recognized this and concluded that Beth Shemesh had “an Israelite population but under the political and economic domination of the Philistines” (from Lester L. Grabbe’s introduction to Israel in Transition). This conclusion jibes with archaeology and the biblical account.

The Bible extensively records details of Philistine domination and oppression during the periods of Samson and Saul (though Samuel briefly expelled the Philistines). Judges 13:1 and 14:4 say that God gave Israel over to the Philistines. Later, 1 Samuel 13:19-23 record that the Philistines had monopolized ironworks and blacksmithing during the reign of Saul, so that “all the Israelites went down to the Philistines, to sharpen every man his plowshare, and his coulter, and his axe, and his mattock.”

Archaeologically, the strata associated with this period in Beth Shemesh yielded an abundance of Philistine bichrome pottery. This form of pottery is certainly evidence of Philistine influence. In addition, though Beth Shemesh did not grow rapidly during this period (probably due to border unrest), the metal industry within the city grew. A few forges and smithies have been uncovered, which serve as stunning corroborations of the scriptures quoted above about the Philistine monopoly over ironworks.

Still, these facts do not support the idea of a Philistine populace. Percentage levels of Philistine pottery remained lower than in Philistine-populated cities such as Ekron or Gath, and evidence of pork consumption (ubiquitous among Philistine sites) has not been found in Beth Shemesh, though it has been found 4 miles west at the site of Tell Batash (identified as Timna, which was colonized by Philistines—Judges 14:1).

Therefore, evidence points to a late-judges-period Beth Shemesh as described in the biblical account, with no reason to think otherwise—an Israelite populace at the site, but under Philistine dominance.

Samson’s Stomping Grounds

This is the scene from which Samson emerges. Samson’s neck of the woods was “between Zorah and Eshtaol.” These cities are within sight of Beth Shemesh and lie just a few miles north across the Sorek Valley. Samson undoubtedly visited Beth Shemesh, as it was a major city along the route between Zorah, Eshtaol, Timna, and Lehi, where the Bible records Samson traveling. All of these sites would have been under Philistine domination.

Samson’s name in Hebrew is Shimshon (שִׁמְשׁוֹן), which can mean something akin to “sun man.” This name is closely related to “Shemesh.” Prof. Steven Weitzman believes that Samson was named after the city Beth Shemesh, which oversaw his home valley (Tel Beth-Shemesh: A Border Community in Judah, 2016).

Judges 13:5 states that Samson was born to “begin to save Israel out of the hand of the Philistines.” However, Judges 14:1 records that by the time of early adulthood, “Samson went down to Timnah, and saw a woman in Timnah of the daughters of the Philistines.” From the beginning, Samson’s story is dominated by a cultural and ethnic mélange between Israelites (who were behaving much like Canaanites) and the Philistines. Prof. Steven Weitzman wrote of this, “[T]he ethnic ambiguities of the Samson story are no coincidence, for however fictionalized the story of Samson may be, it accurately registers the hybrid character of the Iron Age Shephelah.”

Thus, Samson’s story accurately summarizes the social and ethnic strife and confusion in the region surrounding Beth Shemesh. (For more about Samson and Philistine culture, read “Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Philistines” and “Was Hercules Samson?”)

A discovery with a possible link to Samson has been unearthed in Beth Shemesh. In 2012, a small seal was discovered in a layer that dated to the 11th century b.c.e. This seal depicts, in very primitive imagery, a man fighting with a lion. Samson famously slew a lion in Judges 14:5-6. This discovery could indicate that Samson’s actions were notorious in the region while he still lived and shortly thereafter. (For more on this discovery, read “The ‘Samson’ Seal.”)

The Return of the Ark

In the time of the penultimate judge, Eli, the ark of the covenant was captured by the Philistines. 1 Samuel 4 reveals that the Israelites had idolized the ark, believing that their carrying it into battle would ensure victory (a trope repeated, rather famously, in the modern movie Indiana Jones: Raiders of the Lost Ark). Instead: “And the Philistines fought, and Israel was smitten, and they fled every man to his tent. … And the ark of God was taken …” (verses 10-11). Upon hearing the news, the elderly Eli fell backward out of his seat by the gate of Shiloh and died.

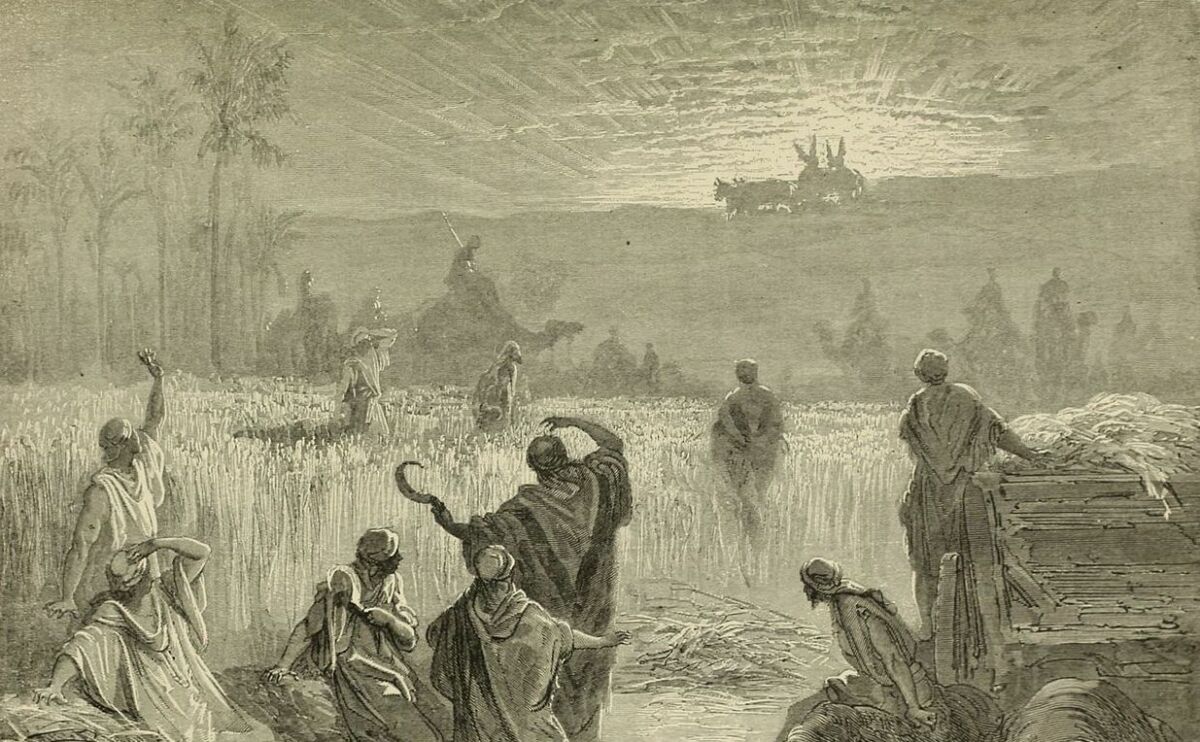

The Philistines retained the ark for seven months. During this period, they suffered from a horrific scourge that, based on the biblical description, brings to mind something akin to the bubonic plague. Recognizing the source of the plague, they restored the ark to Israelite territory in a cart filled with an indemnity of golden objects. Pulled by two cows, the ark traveled 9 miles east through the Sorek Valley to Beth Shemesh, where the Israelite populace received it jubilantly. The Israelites placed the ark on a rock near the city and sacrificed the cows. Later, God killed many locals for peering into the ark. (The number in 1 Samuel 6:19 can be interpreted in a few different ways. The King James Version and Jewish Publication Society Tanakh read 50,070 men; other translations, like the Revised Standard Version, say it was 70 men.) Deuteronomy 10:8 says that only Levites could handle the ark, and Numbers 4:20 forbade even the Levites from viewing the inside of the ark.

This story indicates several critical details about Beth Shemesh. First, as above, the account shows that Beth Shemesh had a primarily Israelite populace. Second, the story reveals that the Israelites were, at best, not familiar with these simple Torah laws; at worst, they did not respect them enough and flouted them. Third, the story reveals geographical details about where the ark was placed. Bunimovitz and Lederman believe they may have found this very location described in the account: the “great stone” where the ark sat in Beth Shemesh. (Image below—for more on this, read “Was This Where the Ark of the Covenant Sat?”)

The ark did not reside in Beth Shemesh for long. The men of the city sent the ark to nearby Kirjath-Jearim, which was deeper within Israel’s interior and more naturally defensible.

Davidic Beth Shemesh

The Bible records that David built a kingdom which had secure borders beyond where Israel had previously expanded. 2 Samuel 5:17-25 record David defeating the Philistines in a pitched battle in the “valley of Rephaim,” a valley that descends southwest from Jerusalem and connects with the Sorek. Later, David would regroup and drive the Philistines out of Israel.

The defeat of the Philistines seemed to provide Beth Shemesh with an exceptional level of prosperity in the late reign of David and the reign of Solomon (10th century b.c.e.). Bunimovitz and Lederman, in an article titled “Renewed Excavations at Tel Beth-Shemesh, Part 1: The Iron Age,” said of the level which they date to the middle-to-late 10th century b.c.e., “Level 3 is the most impressive Iron Age occupation layer exposed in the new excavations. It is in this layer that we encounter the first ‘fingerprints’ of state organization at Iron Age Beth Shemesh, represented by a variety of public buildings spread throughout the site.” This speaks to the new monarchical administration established over the wider region, as described in the Bible.

Probes of the site indicated that the city’s largest fortifications were built at the start of the Iron Age ii (10th century b.c.e.—“Davidic” and “Solomonic” Beth Shemesh). Ironworks in the city expanded in this period, too. Area E, the commercial area of the ancient city, contains the earliest iron workshop yet discovered in Israel, which held two hearths and many ironworking tools. Though Beth Shemesh was temporarily at peace, it was still an important fortification, and it was built up as such.

A large cruciform water reservoir was also hewn out of rock near the city during this period. Its walls were covered in a cement-like plaster up to the ceiling. Stairs descend into the reservoir, and a large cylindrical shaft allowed water to be drawn to the surface. This construction would have helped locals enjoy easier and more consistent access to water. More importantly, it shows that Beth Shemesh was ruled by a centralized government with a labor force who built such public works. 1 Kings 4:9 notes that Beth Shemesh was one of the 12 cities chosen to provide one month’s supplies for Solomon and his house. (For more on Solomon and his public works, read “Rethinking the Search for King Solomon.”)

These discoveries, along with other public structures, indicate that Beth Shemesh was a fortification on the outskirts of an expansive, rich and centralized kingdom. The Bible describes the kingdom of David and Solomon in exactly that way.

Beth Shemesh would remain a prosperous city until it was destroyed (twice) within the following centuries.

A Clash With Joash

2 Kings 14 describes a peculiar conflict between King Joash of Israel and King Amaziah of Judah at the start of the eighth century b.c.e., in which Beth Shemesh played a vital role and suffered its first destruction.

Upon ascending to the throne, Judah’s King Amaziah purged those who had conspired against his father (confusingly also named Joash, like his northern contemporary) and launched a campaign to re-subjugate Edom. After successfully subduing Edom, the foolhardy Amaziah, on a victory lap, tauntingly sent messengers to King Joash of Israel saying, “Come, let us look one another in the face” (2 Kings 14:8).

Joash warned Amaziah against provoking a war between the two nations, “[b]ut Amaziah would not hear” (verse 11). Summarily, the two kings began a short but decisive war. 2 Kings 14:11-12 say, “… So Jehoash king of Israel went up; and he and Amaziah king of Judah looked one another in the face at Beth Shemesh, which belongeth to Judah. And Judah was put to the worse before Israel; and they fled every man to his tent.”

Joash soundly defeated Amaziah, taking him captive (verse 13). Joash then marched his army to Jerusalem, where he toppled a gate and looted the temple. With the booty, Joash returned to Samaria and released Amaziah. Amaziah would outlive Joash by 15 years before being dispatched by conspirators as his father had been.

Why did this battle transpire at Beth Shemesh? Examining a simple map, Beth Shemesh does not appear to be in any significant geographic position between the northern tribes and Jerusalem. However, because of Israel’s complex geography, going through the site of Beth Shemesh makes sense for an army en route to Judah’s capital.

Beth Shemesh is only 15 miles west of Jerusalem. Several valleys cut through the Shephelah and provide easy-to-travel thoroughfares from the seacoast to the hills surrounding Jerusalem. The most eminent of these valleys are the Ayalon, safeguarded by Gezer, and the Sorek, safeguarded by Beth Shemesh. These two routes provide arteries to Jerusalem which were used throughout antiquity. The Tel Aviv–Jerusalem railway follows the Ayalon Valley today, and the older Jaffa–Jerusalem Railway follows the Sorek. If the Israelite army embarked from the Coastal Plain, where vast armies can be more easily amassed than the central highlands, then a battle site in the broad plains of Sorek near Beth Shemesh is logical.

The Bible does not explicitly say that Beth Shemesh itself was sacked as part of Joash’s campaign, but that still seems probable. Archaeologist Yohanan Aharoni, in his book The Land of the Bible, wrote, “It would be contrary to the general rule if Beth-Shemesh was not looted and burned at the same time (if for no other reason, to reward the victorious troops).”

Indeed, Tel Beth Shemesh does show signs of ransacking from this period. Area B contains a pillared public building which was looted and set on fire. Area E was the commercial area, and it shows signs of pottery being smashed before being engulfed in flames. Though surrounding cities were devastated by an earthquake in a slightly later period (read “Amos’s Earthquake: A Mountain of Evidence”), the destruction of Beth Shemesh appears to have been more deliberate. Every pot in Area E was shattered into smithereens, and most of the site was scorched.

Beyond this, a new scientific process in archaeology is beginning to nullify some chronological debates about when sites were destroyed. This burgeoning technique is called archaeomagnetism. (For an explanation and a survey of its results, read “Breakthrough New Geomagnetic Research ‘Reveals the Truth Behind Biblical Narratives.’”) Archaeomagnetism can ascertain a general estimate of when a site was last destroyed by analyzing the magnetism of burnt objects (bricks or pottery) and comparing their magnetic fingerprint with the record of earth’s magnetic field, which is constantly changing. Magnetic study dated a destruction of Beth Shemesh to the early eighth century b.c.e, fitting perfectly with the campaign of Joash.

Therefore, archaeology has revealed that Joash’s victorious troops indeed must have pillaged Beth Shemesh after the battle with Judah. Ancient Beth Shemesh would never quite convalesce after this carnage.

Beth Shemesh Since

Beth Shemesh’s second destruction was during the Assyrian conquest of Judah under Sennacherib, at the end of that same eighth century b.c.e. Again, the Bible does not name Beth Shemesh specifically during Sennacherib’s invasion—although it is clear from the account that the city would have been involved. “Now in the fourteenth year of king Hezekiah did Sennacherib king of Assyria come up against all the fortified cities of Judah, and took them” (2 Kings 18:13). Sennacherib’s own inscriptions attest to his defeat of nearly four dozen Judahite cities at this time (see our online exhibit here for more detail).

Bunimovitz and Lederman wrote, “No evidence of an Iron Age settlement later than the 8th century b.c.e. was uncovered …” (“The Final Destruction of Beth Shemesh and the Pax Assyriaca in the Judean Shephelah”). At least one small coterie of Jews did return to the ruins, but were killed around 670 b.c.e. by Philistines who wished to keep their border with Judah an unpopulated buffer zone. The Philistines took rocks from the ruins of the city and used them to fill the large water reservoir that had helped sustain the city for centuries. This reservoir would be forgotten until it was excavated two and a half millennia later.

Due to the rapid growth of the modern city of Beit Shemesh, the Israeli Antiquities Authority (iaa) has had to enact salvage excavations surrounding the site of Tel Beth Shemesh. These salvage excavations are meant to uncover structures and artifacts in a rapid yet systematic fashion, before sites are covered by sprawling, modern city infrastructure. The first salvage excavation actually occurred in the late 1960s, before the construction of Highway 38 just outside of modern Beit Shemesh. Salvage excavations in 2018 under Dr. Yehuda Govrin discovered an ancient suburban settlement further into the Sorek Valley, near the base of Tel Beth Shemesh, which was evidently a center for olive oil production under the Assyrian and Babylonian empires. Govrin wrote that this discovery was significant because “the development of the area took place lower down, at the foot of the Tel. Any rebuilding of the Tel might have suggested a potential rebellion. But lower down, development was permissible.” This detail shows that Tel Beth Shemesh was not repopulated throughout the Assyrian and Babylonian stages because those empires forbade the action. The findings of most salvage excavations near Tel Beth Shemesh are still awaiting publication.

A few Byzantine- and Islamic-period structures were later constructed near the ruins of Tel Beth Shemesh. One famous Byzantine church structure is the “Church of the Glorious Martyr,” built by Justinian in the sixth century c.e. A small Arab village named Ain Shems arose near the ruins of the city, around a mosque called Weli Abu Meiser.

Modern Beit Shemesh has a population of about 150,000 people. The city began to be built in 1952 by Jewish immigrants. The modern city of Beit Shemesh grew just outside of its ancient ruins. Though not yet one of Israel’s top 10 biggest cities, Beit Shemesh is growing rapidly.

Beit Shemesh today stands well within the borders of Israel, and is experiencing relatively peaceful times. In the middle of the modern city is a place called Gan Golan. Gan Golan is a park dedicated to an officer who died serving in the idf during the First Intifada. The park contains unique sculptures, including depictions of David playing the harp, the tables of the law, a sculptured head of Samson, and the ark returning to Beth Shemesh on a cart—all excellent reminders of the storied history of Tel Beth Shemesh.

Articles in This Series:

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Ai

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Azekah

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Beersheba

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Beth Shean

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Beth Shemesh

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Dan

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Ekron

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Gath

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Gezer

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Hazor

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Hebron

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Jericho

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Jerusalem

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Khirbet Qeiyafa

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Lachish

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Megiddo

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Mizpah

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Samaria

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Shechem

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Shiloh

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Sodom

Videos in This Series:

Touring the Bible’s Buried Cities: Gezer