The book of Jonah is a short, four-chapter book best known for the “great fish” account, as well as the “taming” of the Assyrians—something that, to the surrounding nations at the time, might have seemed even more miraculous than surviving three days in the belly of a sea creature. It’s also a story that is eaten alive by the critics.

The most cursory analyst is likely to come across the following about the prophet on Wikipedia:

The consensus of mainstream biblical scholars holds that the contents of the book of Jonah are entirely ahistorical. Although the Prophet Jonah allegedly lived in the eighth century b.c.e., the book of Jonah was written centuries later during the time of the Achaemenid [Persian] Empire. … Many scholars regard the book of Jonah as an intentional work of parody or satire. If this is the case, then it was probably admitted into the canon of the Hebrew Bible by sages who misunderstood its satirical nature and mistakenly interpreted it as a serious prophetic work.

“Entirely ahistorical.” It’s a brutal summary. Is it fair?

Of course, from an archaeological perspective, there is nothing to be said for the “great fish” part of Jonah’s story (although if you want to read more about that, see our article here). What can be spoken for, historically, is virtually everything else in the account. Let’s examine the book of Jonah and see how it compares to the “evidence on the ground”—and a remarkable period in Assyria’s history.

Setting the Scene—a ‘Bloody City’

According to biblical chronology, the Prophet Jonah was on the scene during the first half of the eighth century b.c.e., during the prosperous reign of King Jeroboam ii (2 Kings 14:25—outside the book of Jonah, this is the only other passage in the Hebrew Bible in which the prophet is mentioned). Jonah 1:1-2 state:

Now the word of the Lord came unto Jonah the son of Amittai, saying: ‘Arise, go to Nineveh, that great city, and proclaim against it; for their wickedness is come up before Me.’

And so, as is well known, the prophet immediately fled from his commission by sea, heading to Tarshish—precisely the opposite direction of Assyria (verse 3). The start of this book does not specify exactly what Assyria’s “wickedness” was, nor does it state why Jonah was so fearful. But we do get an idea toward the end of the book that God’s punishment was for the “evil way” of “every one,” for “the violence that is in their hands” (Jonah 3:8). And we get a truly vivid picture of Assyria’s violent early-eighth-century b.c.e. status, and thus Jonah’s trepidation, thanks to various archaeological discoveries including inscriptions, wall reliefs and other artifacts.

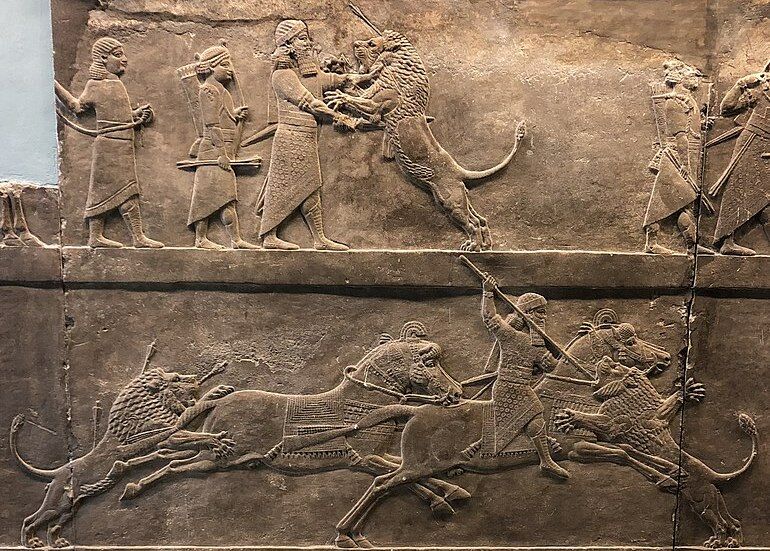

One famous Assyrian leader of the century prior was Ashurnasirpal ii (circa 883–859 b.c.e.). This king was known for hanging his enemies on posts, flaying them, and lining city walls with their skins. He also burned his enemies, or beheaded them if they were fortunate—those still alive would have noses, ears, eyes, arms and other extremities removed.

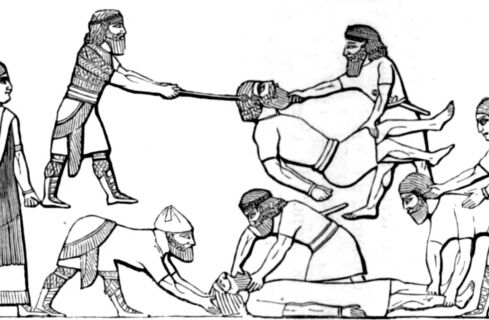

His son Shalmaneser iii (858–824 b.c.e.) continued in his footsteps. His famous bronze Balawat gates (see above; Balawat was a city near Nineveh) depict Assyrian soldiers hacking apart the captured enemy alive, dismembering hands and feet. Heads were hung from walls during his reign, and impaled captives were lined up on display. “Pillars” of skewered human heads stood like totem poles.

Another later example of Assyrian brutality, King Esarhaddon (seventh century b.c.e.) recorded on one of his prisms his parading of conquered nobles through the streets—wearing “necklaces” of the decapitated heads of fellow nobles around their necks. Another records a defeated Arabian leader being taken to Nineveh and made to live in a kennel alongside the dogs that guarded the city gates. On King Sennacherib’s prism inscriptions (late eighth century b.c.e.), the ruler bragged about creating so much blood from death and disembowelment that his horses waded through it like a river. Sennacherib gratuitously describes ripping out men’s testicles “like the seeds of summer cucumbers.” As for the city of Nineveh itself, to whom Jonah was directed—the Prophet Nahum aptly describes it specifically as “the bloody city” (Nahum 3:1).

This was the kind of terror faced by enemies of the Assyrian Empire at the time of Jonah. While the later Persian Empire sought to keep conquered peoples in the fold through mercy and favor, the Assyrians sought to keep their empire together by way of the opposite extreme: terror. No wonder the prophet was fearful of carrying God’s warning message—and conversely, no wonder God’s threat of divine destruction.

A ‘City of Three Days’ Journey’

We’ll skip forward to Jonah 3 (the “Jonah and the whale” account will save for another day). Here Jonah submits to God’s will and sets out on his journey to Assyria. Verses 3-4:

… Now, Nineveh was an exceeding great city, of three days’ journey. And Jonah began to enter into the city a day’s journey, and he proclaimed, and said: ‘Yet forty days, and Nineveh shall be overthrown.’

Here we start to see a description of a truly gargantuan city. Nineveh during this period served as chief city of the Neo-Assyrian Empire—and archaeological evidence bears out the truly domineering nature of this city. (During at least the seventh century b.c.e., historians consider Nineveh the largest city in the world.) Jonah describes the city as “three days’ journey” in size. That is, of course, an exaggeration. Or is it?

The meaning of this passage is unclear, and there are a couple of ways this could be taken. One good option is the circumference of the city (ancient measures of cities typically noted their size by circumference). The city-mounds of Kouyunjik, Nimrud, Karamless and Khorsabad form a parallelogram edge around this Assyrian territory. Accounting for these as part of the wider Nineveh area gives us a circumference of around 60 miles (about 95 kilometers). Given that a “day’s walk” is 20 miles (just over 30 kilometers—the fifth-century b.c.e. historian Herodotus also specifies this “days’ walk” distance), the circumference exactly three times larger fits perfectly with the Jonah account. (See The Cambridge Bible for Schools and Colleges here for more information.)

This agrees with other secular historians, such as the first-century b.c.e. Greek historian Diodorus Siculus, who recorded that Nineveh was 480 stadia in circumference (89 kilometers). The historian Strabo, of the same century, writes that Nineveh was “much greater” than Babylon—and he states that “the circuit of [Babylon’s] wall is 385 stadia” (71 kilometers). The fifth-century b.c.e. historian Xenophon records that Nineveh’s city walls were some 30 meters tall and 15 meters thick. And within that territory, excavations have revealed that the central city hub of Nineveh included an area of roughly 2,000 acres.

(As a side: The modern territorial area called the “Nineveh Plains,” encompassing ancient Nineveh, is roughly 90 kilometers from edge-to-edge—again, a three-day journey.)

Jonah’s account also exhibits another certain geographical tidbit, pointed out by Craig Davis in his book Dating the Old Testament:

Jonah left Nineveh and watched it from the east (4:5). Nineveh was located on the east bank of the Tigris River, with hills east of the city. This would give Jonah a good vantage point to view the city, as well as an early view of any enemy army [that Jonah would have expected to fulfill the curse—Jonah 3:4], which would need to approach Nineveh from his side of the river.

He also notes the following, about Nineveh’s population (verse 11):

An ancient Assyrian inscription indicates that the city of Calah, Assyria, which was not as large as Nineveh, had 69,574 inhabitants in 879 B.C. This would mean the Jonah 4:11 population of Nineveh (120,000), 100 years later is in the right ballpark …

These points of accuracy would seem unlikely in a post-exilic allegory.

Mourning Horses

Of course, the destruction that Jonah warned about never came—by some miracle, the Assyrian king actually called for the repentance of his city. Jonah 3:7-8 records the king’s decree:

“Let neither man nor beast, herd nor flock, taste any thing; let them not feed, nor drink water; but let them be covered with sackcloth, both man and beast, and let them cry mightily unto God ….”

Now this is something truly peculiar. The Bible records humans fasting on numerous occasions. But animals fasting and wearing sackcloth? This was no ordinary Israelite practice.

We do have a sense of this type of practice from this part of the world, however, related by the fifth-century b.c.e. Greek historian Herodotus. He describes an act of the neighboring Persians (not the Assyrians, but still representing these Asiatic peoples and their customs):

When the cavalry returned to camp, Mardonius and the whole army mourned deeply for Masistius, cutting their own hair and the hair of their horses and beasts of burden, and lamenting loudly. … So the barbarians honored Masistius’ death in their customary way. (The Histories, Book 9, 24.1-25.1)

Apparently for the people of this Mesopotamian/Eastern region, the mourning of animals is described as a “customary way.” The first-century c.e. historian Plutarch recorded similar acts.

The mention of horses mourning fits with Jonah 3:7; since beasts are listed separately to herds and flocks, it is believed to refer to Assyrian horses.

A Peculiar Political Situation

As the book relates, Nineveh was spared destruction thanks to the repentance of the king and populace. This is where things get really interesting.

Because something very peculiar happens to Assyria during this precise window in the eighth century: They stop going to war.

Let’s step back and look at the wider geopolitical picture. Pairing the book of Jonah with 2 Kings 14:25, we can roughly date the book to the latter part of the first half of the eighth century b.c.e.—around 770–750 b.c.e. This fits into a very unusual period in Assyrian history, known as the “Period of Stagnation” (783–745 b.c.e.), which lasted through the reigns of three successive kings.

The first king during this period, Shalmaneser iv (circa 783–773 b.c.e.) maintained the normal, yearly military campaigns for most of his reign. Still, his rule was marked by an apparent decentralization of power and the rise of lesser officials (like General Shamsi-ilu) taking on greater-than-normal roles and responsibility. There is a sense of this in the book of Jonah—after all, the book does not mention Assyria, but rather Nineveh and the king specifically. Or, perhaps the two names were somewhat more synonymous during this time—again, if Nineveh included the parallelogram-territory of Kouyunjik, Nimrud, Karamless and Khorsabad, at the heart of Assyria. Whatever the answer, little is known from the reigns of Assyria’s kings during this 40-year period—and there is a reason for that.

What little is known is witnessed on the Limmu, or Eponym, Lists. These are official Assyrian lists that document, year-by-year, a short sentence about what occurred in the empire that year, alongside the name of a lottery-drawn governor. For example, the following eponyms:

During the eponymy of Inurta-ashared, governor of Raqmat, campaign against Chaldaea.

During the eponymy of Shamash-kumua, governor of Arrapha, campaign against Babylon.

These represent the years 812 and 811 b.c.e. As can be seen, there is a governor’s name, and most often a reference to a military campaign undertaken by the king of Assyria, which was normally done on a yearly basis. (These invaluable year-by-year limmus span several centuries of the Assyrian Empire—right back into the Old Assyrian Empire. They are standardized lists, several of which have been discovered from different parts of the empire.)

Back to the first king of our eighth-century “Period of Stagnation,” Shalmaneser iv. A military campaign took place every single year throughout his reign, and then continued on into the reign of the following king, Ashur-dan iii. His first four eponym years (with himself listed in the first one) are as follows:

During the eponymy of Aššur-dan [iii], king of Assyria, campaign against Gananati.

During the eponymy of Šamši-ilu, the commander in chief, campaign against Marad.

During the eponymy of Bêl-ilaya, governor of Arrapha, campaign against Itu’a.

During the eponymy of Aplaya, governor of Mazamua, the king stayed in the land.

During this fourth year (circa 769 b.c.e.), the king stayed in the land. This is all the more remarkable when considering that every prior year, for41 years without fail, there was a campaign.

Beginning of the End

No explanation is given for why the “king stayed in the land” (sometimes an explanation is given, despite the brevity of each line). This kind of behavior, without good reason, did not last long—it was not seen as befitting an Assyrian king. Either the king went to war or he was overthrown. The last time a king did “stay in the land,” 41 years earlier, was the same year the then-elderly king died.

As such, the following years of Ashur-dan iii’s reign saw Assyria return to the campaign trail. Here are the continuing eponyms:

During the eponymy of Qurdi-Aššur, governor of Ahizuhina, campaign against Gananati.

During the eponymy of Mušallim-Inurta, governor of Tille, campaign against Media.

During the eponymy of Inurta-mukin-niši, governor of Habruri, campaign against Hatarikka; plague.

During the eponymy of Sidqi-ilu, governor of Tušhan, the king stayed in the land.

Plague on the Ashur-dan iii’s empire, followed by another year of staying put. This was where everything began to crumble for the king. For the next five years (listed below), no campaigns took place, only revolts, plague and even an eclipse—a foreboding sign for the deeply superstitious Assyrians (and one that may be referenced in Amos 8:9, fitting with this time period). These are the following five years:

During the eponymy of Bur-Saggile, governor of Guzana, revolt in Libbi-ali; in Simanu eclipse of the sun.

During the eponymy of Tab-bêlu, governor of Amedi, revolt in Libbi-ali.

During the eponymy of Nabû-mukin-apli, governor of Nineveh, revolt in Arrapha.

During the eponymy of La-qipu, governor of Kalizi, revolt in Arrapha.

During the eponymy of Pan-Aššur-lamur, governor of Arbela, revolt in Guzana; plague.

In fact, from that very first year Ashur-dan iii “stayed in the land” to the end of the reign of the next and final “stagnant” king, Ashur-nirari v, campaigns took place during only eight years out of 23. Ashur-nirari v “stayed in the land” for his first five years and campaigned in only two out of the nine years that he was on the throne.

This does not happen in the mighty Assyria. What happened?

The (Temporary) Neutering of an Empire

Given the real lack of discoveries relating to the reigns of Ashur-dan iii and Ashur-nirari v, besides these lists, historians cannot be sure. What is sure is how well the “Period of Stagnation” fits in with the account in the book of Jonah, as well as 2 Kings.

It is interesting to speculate. Perhaps Ashur-dan iii “stayed in the land” during the fourth year of his reign—the first time something like that happened in 41 years—thanks to Jonah’s warning message. The 760s b.c.e. date would certainly fit. And perhaps in the year following, the political pressure to go back out and campaign became too much, the king succumbing and campaigning three years in a row, before unbelievable calamity hit: repeat plagues, numerous revolts, even an eclipse. Could this “series of unfortunate events” be related in some way to God’s threat of “overthrow” (Jonah 3:4) for Nineveh, unless they ceased hostilities? God eventually forcing the king to “stay in the land”? And could such a series of events, keeping Assyria at bay, be directly related to God’s “saving” of Israel during the reign of Jeroboam ii (see 2 Kings 14:27), giving the Israelite nation one last chance to repent before being overthrown by Assyria? (Amos 7:8, King James Version; Isaiah 10:5).

This is the very message relayed by the first-century Jewish historian Josephus—that God intended Assyria’s status of “world domination” to be quelled at this time. He writes:

Jonah had been commanded by God to go to the kingdom of Nineveh; and when he was there, to publish it in that city, how it should lose the dominion it had over the nations … he stood so as to be heard, and preached, that in a very little time they should lose the dominion of Asia. (Antiquities, 9.10.2)

The impotent Ashur-nirari v reigned nine years before he was overthrown around 745 b.c.e. by a new king who would finally end the “Period of Stagnation”: the infamous Tiglath-Pileser iii. Tiglath-Pileser immediately began campaigns against foreign nations, including the unrepentant Israel, as prophesied (Isaiah 10:5, 2 Kings 15:19, 29). From this king onward, the Bible identifies the next full century of powerful Assyrian leaders directly by name, and describes in detail their conquests and deportations of Israel and Judah—Tiglath-Pileser, Shalmaneser v (2 Kings 18:9), Sargon ii (Isaiah 20:1), Sennacherib (2 Kings 18) and Esarhaddon (2 Kings 19:37).

And Virtually Everything Else

We could go on. The book of Jonah is filled with tight-fitting, historically proved details: the shipping port Joppa (Jaffa), which was functioning at the time (Jonah 1:3); the well-attested practice of casting lots (verse 7); the large merchant vessel replete with hold, sail and rowing capability, befitting merchant travel of the time (verses 3, 5, 13). Even the Aramaic language in relation to the sailors: Some have criticized the book of Jonah as a late imagination, thanks to its use of Aramaic. This might be the case if the entire book was in Aramaic (which the Jews adopted following the sixth-century b.c.e. Babylonian captivity), but there is only a very small amount of Aramaic in the book—and at that, specific to the section about the sailors, who would at the time most likely have been the Aramaic-speaking Syro-Phoenician merchants known from the period. (And the destination, Tarshish, is believed to be a Phoenician port—verse 3.) Regarding the language, Craig Davis continues:

There are no Persian words in Jonah. The early pronoun “anoki” is used twice. These facts favor the idea that Jonah was written before the exile, rather than the post-exilic Persian period.

And what about even the “gourd” that grew up over Jonah to shade him, as he set up camp east of the Nineveh to watch its destruction (Jonah 4:6)? This word is believed to refer to the castor oil plant Ricinius communis. This plant appears to be mentioned in Assyrian medical text as a drug whose effects precisely match that known to Ricinius (A Dictionary of Assyrian Botany, R. Campbell Thompson). The plant has broad leaves. The Bible describes the plant quickly sprouting up by divine miracle—but even of its own, Ricinius is known for rapid growth and is an important plant throughout the arid East.

As for the “worm” that killed the plant? (verse 7). This was no normal “worm” (the arid environment not being particularly “worm-friendly”—verse 8). The Hebrew word actually refers to a small insect known as a “crimson worm,” or Coccus ilicis. It is from crushing these insects that red dye was created in the ancient world (something that still continues today with the farming of the related Cochineal beetle; this is a common ingredient in the Western world for dying food and drink products red). Aside from farming for their dye, the Coccus family is a major pest for crops, and the insects can thrive in desert-type environments, as at Nineveh. These insects are known throughout the ancient Near East.

The Book of Jonah concludes as follows:

And the Lord said: “Thou hast had pity on the gourd, for which thou hast not laboured, neither madest it grow, which came up in a night, and perished in a night; and should not not I have pity on Nineveh, that great city, where in are more than sixscore thousand persons that cannot discern between their right hand and their left hand, and also much cattle?” (verses 10-11)

Why It Matters

Why does establishing the accuracy of Jonah’s account matter?

Back to the vein of the introduction: There is a continual and significant debate as to when the books of the Bible were written. “Traditionalists” believe in the books written as described (i.e. Moses is author of the Torah; Isaiah is author of his book of the same name, etc). Conversely, the largely secular “minimalist” camp deemphasizes the significance and power of ancient Israel as described in the Bible, ascribing the Hebrew texts to imagined accounts written centuries later—primarily in the post-exilic period, after the Babylonian captivity.

The language of this minimalism is well relayed throughout Jonah’s above-mentioned Wikipedia page—the one article most likely to pass in front the eyes of the cursory analyst—citing a number of scholarly sources:

The views expressed by Jonah in the book of Jonah are a parody. … The primary target of the satire …. The book of Jonah also employs elements of literary absurdism … a stock trope … the description of the livestock in Nineveh fasting alongside their owners is “silly” … the figure of Jonah himself is entirely legendary.

It is with this typical language that the common Jew, Muslim and Christian—all who respect Jonah as a prophet—are held in open contempt. As for Christianity: Jesus is recorded as believing the account, saying that “Jonas was three days and three nights in the whale’s belly”—Matthew 12:40 (kjv). (In fact, Jesus hung proof of his messiahship solely on this “great fish” event in Jonah—see Matthew 12:38-40; 16:4; Luke 11:29). It’s a pity; to quote the same article, he must have “misunderstood its satirical nature and mistakenly interpreted it as a serious prophetic work.” Oh, to be enlightened.

A popular minimalist theory about Jonah is that it was written around 450 b.c.e., during which post-exilic period Ezra and Nehemiah were forbidding the Jews from engaging in interracial marriage with Gentiles (Nehemiah 13:23-29). As such, the theory goes that the book of Jonah was conjured up as a sort of “angered response” to show the possibility of Gentile conversion. It’s a cute idea—but one for which there is no evidence. And if the emphasis is on evidence—as it should be—then the theory does not hold a candle to the face-value, traditionalist account.

As we have seen, the book of Jonah contains detailed knowledge of Nineveh (a city long since destroyed by the post-exilic period), and fits remarkably well into a brief window of time in Assyria’s history. Numerous other circumstantial details fit.

“Entirely ahistorical”? Ha!