Some may be surprised to find out that the Bible contains a number of references to other texts and ancient sources. A “Book of Jasher,” for example, is quoted in Joshua 10:12-13 and 2 Samuel 1:17-19. Given the content, it is believed to have been a book of poetry. Numbers 21:14-15 quote from a “Book of the Wars of the Lord.” 1 Kings 11:41 references the “Book of the Acts of Solomon.” 2 Chronicles 13:22 is one of many passages referencing a “Commentary of the Prophet Iddo.” The “Chronicles of the Kings of Israel” and “Chronicles of the Kings of Judah” (separate from the biblical books of Chronicles) are also both cited numerous times in relation to the deeds of various kings of Israel and Judah. These are just a handful of examples.

Buried within the first pages of the Bible are some of the most intriguing potential references to other such texts. They have some fascinating early archaeological parallels and are connected to an interesting theory relating to the earliest composition of the Bible.

You’ve likely heard of the Documentary Hypothesis (or jedp Theory)—a popular minimalist theory for the very late formulation (or fictionalization) of the Hebrew Bible. But have you heard of the Wiseman Hypothesis—otherwise known as the Genesis Tablets Theory—an alternate view, arguing an extremely early development of the biblical text?

Setting the Scene: Darwin and the Documentary Hypothesis

The Torah, or Pentateuch—the first five books of the Bible—is traditionally ascribed to the hand of Moses sometime during the second half of the second millennium b.c.e. And the first book—the book of Genesis—has historically played a key role in shaping the worldview for believers of creation.

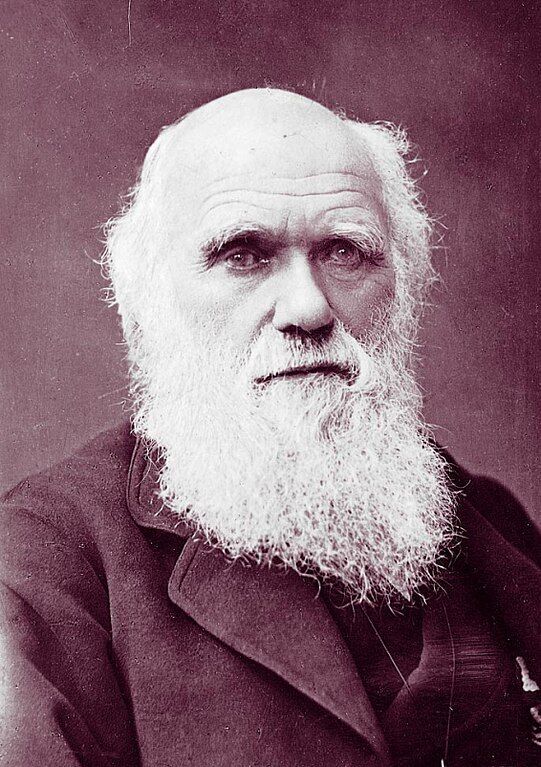

In the late 19th century, however, secularism “struck a blow” at a literalist interpretation of Genesis and the wider Torah accounts with a one-two punch. In 1859, Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species, propounding the theory of evolution. Following this, the “Documentary Hypothesis” was essentially completed in 1878 with the publication of Julius Wellhausen’s Prolegomena to the History of Ancient Israel.

The Documentary Hypothesis essentially reframed the Torah as not coming from the scribal hand of a second-millennium b.c.e. Moses, but rather as the cleverly concocted product of far later Jewish authors (even later than the biblical prophets)—authors fictionalizing a narrative blend of previous traditions, associated with different deities (or deity-names) into a single united text.

The jedp Theory characterized the Torah as a mish-mash compilation of texts from a “Jehovist” (J, or Yahweh-worshiping) author following traditions of the southern kingdom of Judah; an “Elohist” (E, Elohim-worshiping) author following traditions of the northern kingdom of Israel; and a progressive blending of both with additive and redactive work by later “Deuteronomist” (D) and “Priestly” (P) authors. For example, it saw verses using the divine name Yahweh/Jehovah as the product of the “J” writer, and verses using the divine name Elohim as the product of the “E” writer.

Both theories—Darwinian evolution and the Documentary Hypothesis—have had a profound impact on the spheres of religion and science in the century and a half since their development. Both theories continue to be popularly taught today in their respective education centers. But this, despite the fact that both—particularly over the past several decades—have been so hollowed out as to now be effectively regarded by many as disproved.

Of the Documentary Hypothesis, Emory University’s Tam Institute for Jewish Studies sums it up in the following statement: “In the last two decades of Pentateuchal scholarship, the source-critical method has come under unprecedented attack; in many quarters it has been rejected entirely …. [Various factors] have led scholarship to the brink of abandoning the four sources, J, E, P and D.” And as for Darwinian evolution, a recent Guardian article titled “Do We Need a New Theory of Evolution?” highlighted such an implosion in the theory, to the point that it is often said that if Darwin were alive today—based on his own misgivings during his lifetime—he would have abandoned it.

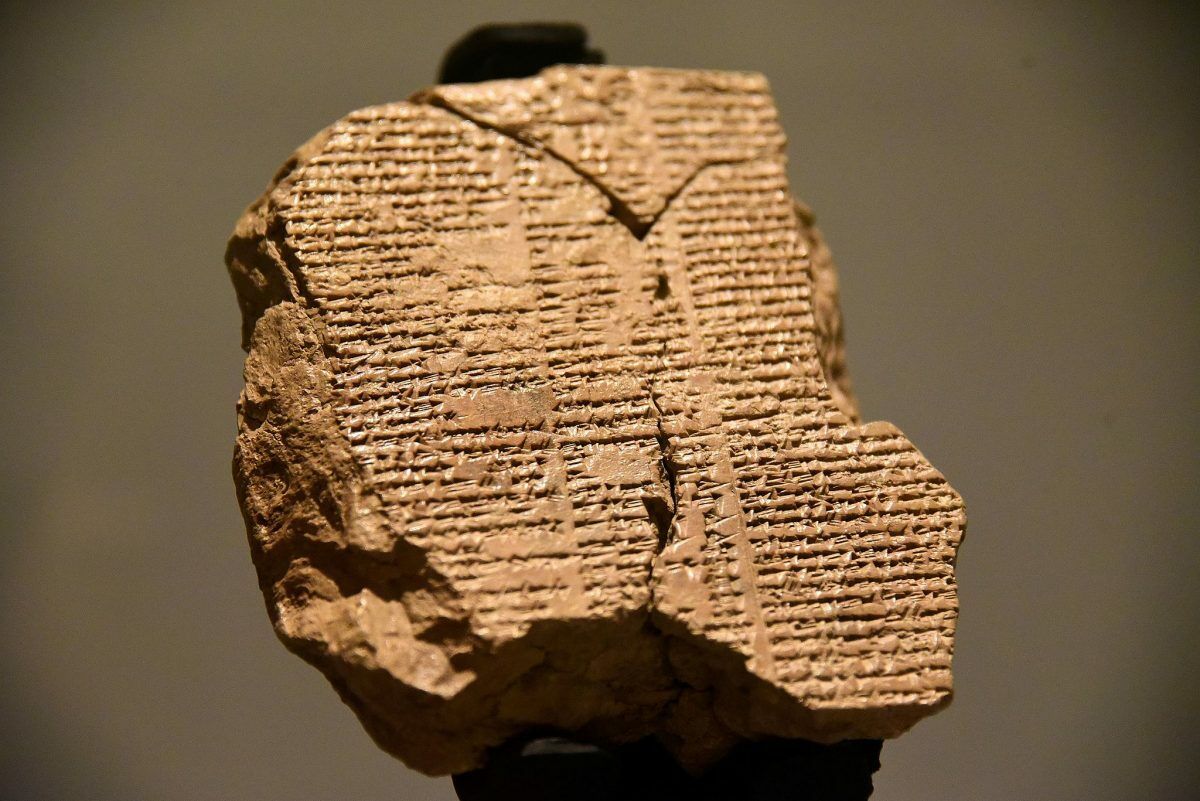

But Darwinian evolution aside: As early as the 1930s, there was significant pushback to the Documentary Hypothesis and its explanation of the authorship of Genesis in particular. The antiquity of the Torah account as a whole was progressively being realized and affirmed, with the deciphering of cuneiform and hieroglyphic inscriptions. These inscriptions corroborated numerous particulars in the biblical account relating to events, customs, names, even sayings and prices of the second millennium b.c.e.—contrary to the supposition made by the Documentary Hypothesis: that the Torah was a late, disconnected pre-Exilic (and in many areas even post-Exilic) work.

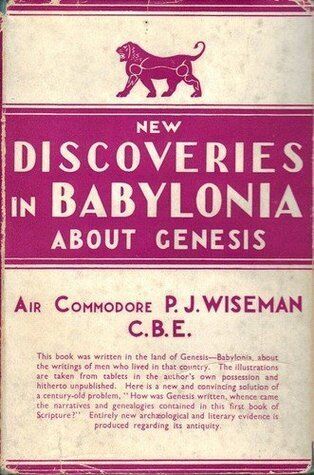

In light of these cuneiform discoveries, a new and opposing theory relating to the early composition of Genesis was introduced by raf Air Commodore Percy Wiseman cbe, with the 1936 publication of his book New Discoveries in Babylonia About Genesis.

Enter the Wiseman Hypothesis

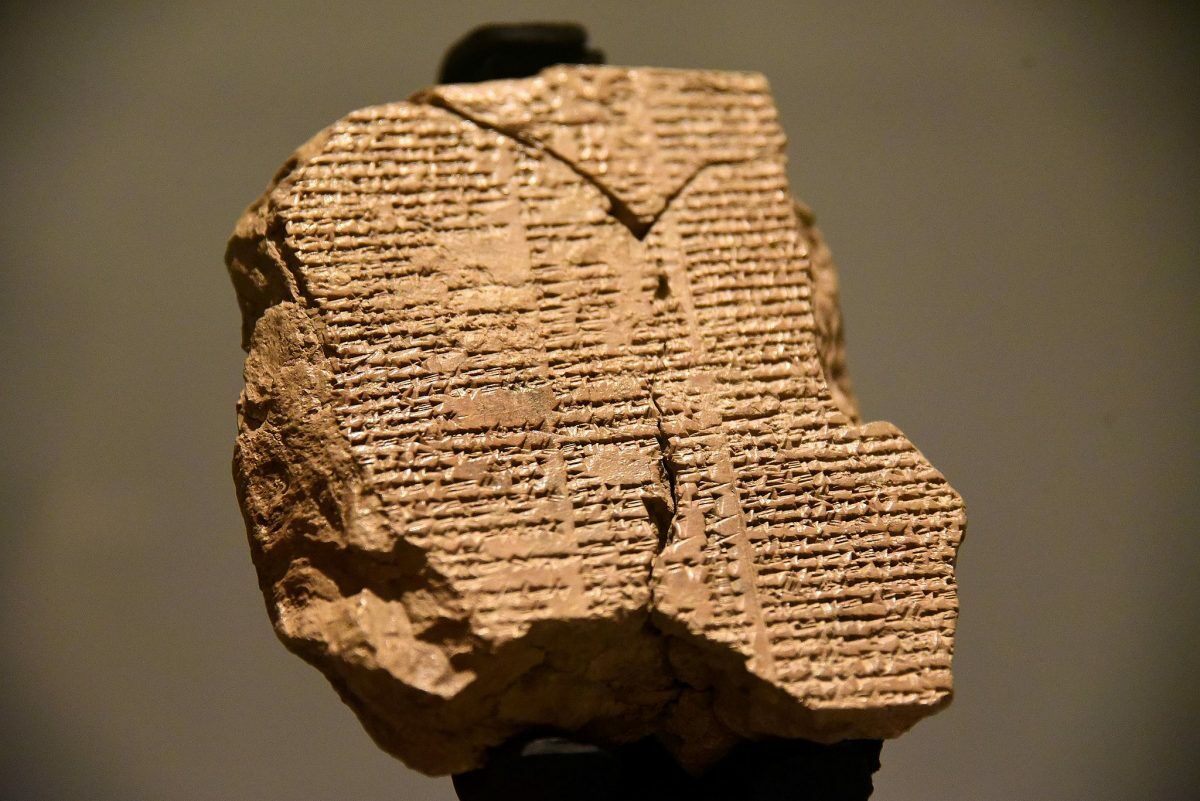

Wiseman, who traveled the Middle East extensively, wrote several books on archaeology and the Bible. He followed general traditional wisdom in recognizing the overall Torah as being compiled by Moses. Yet he proposed that some of the very earliest passages of Genesis referenced and represented additional, pre-existing source material. He hypothesized that these earliest texts were most likely originally inscribed in cuneiform on clay tablets, in the practice typical of the late third to second millennium b.c.e.

In the introduction to his book, Wiseman wrote: “While prevailing theories [i.e. the Documentary Hypothesis] have been unable to unlock the door to [Genesis’s] literary structure, it is submitted that the following explanation does …. It will be seen that these [Bible-critical] conjectures would never have seen the light of day, had scholars of that time been in possession of modern archaeological knowledge.”

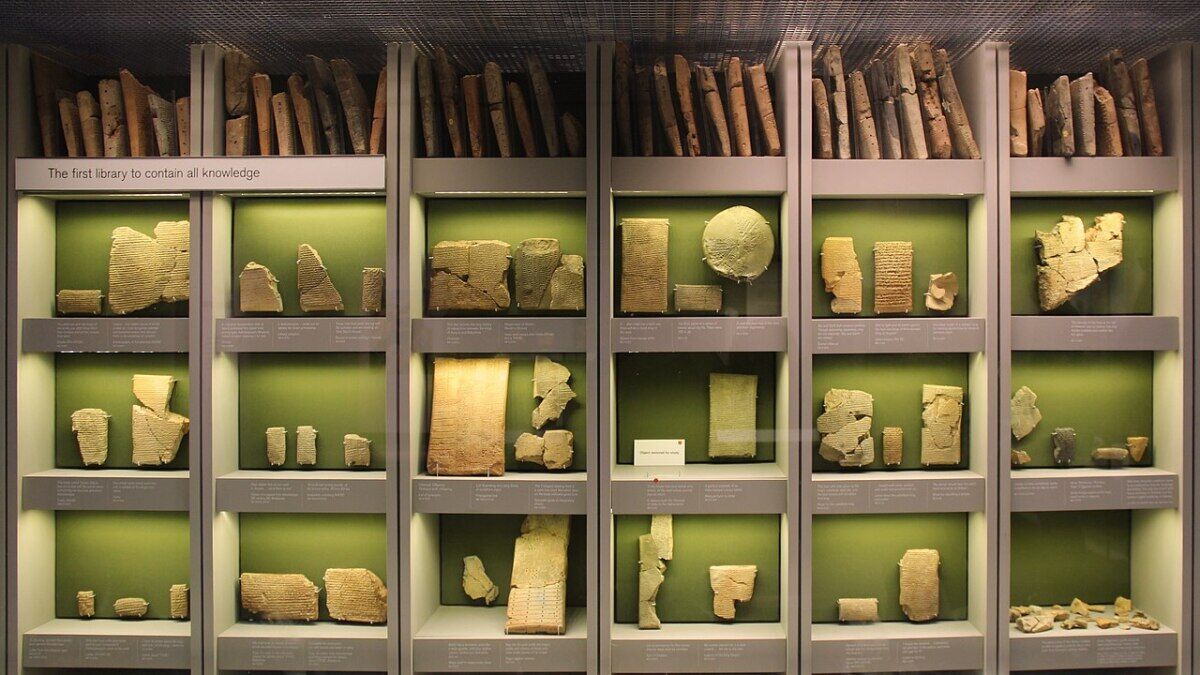

Wiseman noted the vast quantities of cuneiform texts emerging from Babylonian sites and others across the Middle East over the century leading up to his publication. “However, it is only in the last few years that excavation has reached back to the times outlined in the early chapters of Genesis,” he wrote. “The discoveries in Assyria and Babylonia during last century rarely took us back beyond the age of Moses.”

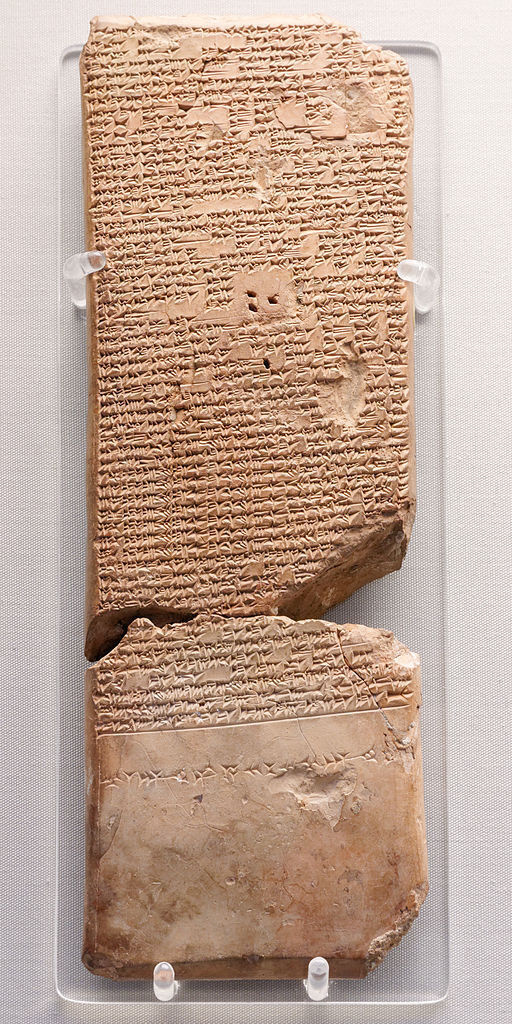

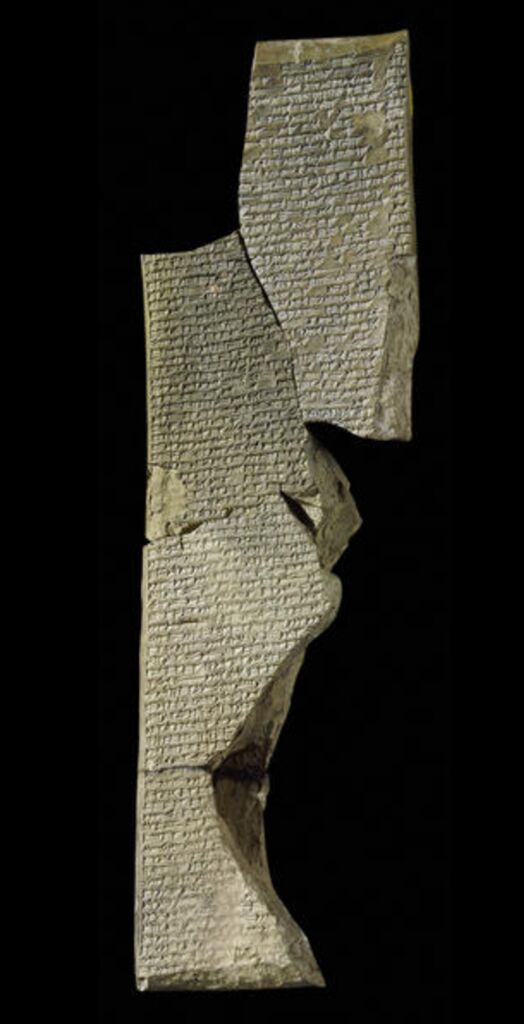

In observing these very early cuneiform inscriptions, Wiseman noted their conclusions included a colophon—a separate line added to the end of an inscription, giving information about the text and/or authorship (see right, for an example). Assyriologist Christine Proust summarized these features on Mesopotamian clay tablets going back to the Old Babylonian period: “[C]olophons are generally placed at the bottom of the reverse of a tablet, and are separated from the main text by a blank space, a single line or a double line” (“Reading Colophons From Mesopotamian Clay-Tablets Dealing With Mathematics”).

“The colophons may contain different kinds of components. The presence of a date, a proper name, a doxology or a catchline is documented,” she wrote. “Another important component of colophons is what one might call a ‘title’ or a ‘label,’ that is, a key word or short phrase that indicates the content of the text to which the colophon is attached.”

Wiseman noted these concluding tablet colophons in his research and saw parallels for them in the following peculiar biblical statements, all found within the first part of the book of Genesis—dealing with the pre-Mosaic, antediluvian and patriarchal world:

- Genesis 2:4: “These are the generations of the heaven and of the earth ….”

- Genesis 5:1: “This is the book of the generations of Adam ….”

- Genesis 6:9: “These are the generations of Noah ….”

- Genesis 10:1: “[T]hese are the generations of the sons of Noah ….”

- Genesis 11:10: “These are the generations of Shem ….”

- Genesis 11:27: “[T]hese are the generations of Terah ….”

- Genesis 25:12: “[T]hese are the generations of Ishmael ….”

- Genesis 25:19: “[T]hese are the generations of Isaac ….”

- Genesis 36:1: “[T]hese are the generations of Esau ….”

- Genesis 36:9: “[T]hese are the generations of Esau ….”

- Genesis 37:2: “These are the generations of Jacob ….”

The peculiarity of these biblical lines raises several logical questions. Why this peculiar framing of the Genesis text with these lines? Why is such language found with such repetition for this early, pre-Mosaic period? These statements are not found ubiquitously throughout the Bible.

What does this term “generations” (Hebrew, toledot) really mean? Indeed, certain of these above statements are associated with literal “generational” lists—and this has long been a standard interpretation of these statements. But by the same token, several of these passages are not accompanied by genealogies, on either side of them (e.g. Genesis 2:4; 6:9; 25:19; 37:2). Actually, this word toledot can also mean “history” or “account” and is rendered this way in several translations.

Wiseman made further observations about the peculiarity of these statements. “The record following, ‘These are the generations of Isaac,’ is not so much a history of Isaac as that of Jacob and Esau. Similarly, after ‘These are the generations of Jacob’ we read mainly about Joseph; in fact this peculiarity has puzzled most commentators. It is therefore clear that this phrase is not an introduction or preface to the history of a person as is so often imagined.”

Introductions? Rather, Conclusions

Considering these questions, and based on similar cuneiform tablet parallels with concluding colophon text, Percy Wiseman theorized that each of these statements represented an end-citation of a “book,” in a sense—an early source text or tablet used by Moses in compiling these earliest passages of Genesis.

Of this conclusion, Craig Davis notes in his 2007 work Dating the Old Testament: “Wiseman’s case is strengthened by the slight variation in wording in [Genesis] 5:1, ‘This is the book of the generations of Adam,’ and the wording in the Septuagint in [Genesis] 2:4, ‘This is the book of the generations of the heavens and the earth,’ implying that those sections were once independent books,” or tablets that contained such material.

As colophons, then, these above-mentioned statements would frame the preceding text. So Genesis 2:4 frames material in the the preceding verses, rather than starting the following passage.

There are some apparent exceptions to the rule, as pointed out by Davis. For example, in the accounts of “Ishmael” and “Esau,” the statements appear to best precede the information that follows, rather than conclude the information that precedes. Yet overall, Davis concurs with Wiseman’s hypothesis as generally providing the best explanation for the presence and use of these peculiar, repetitious scriptural statements in the early Genesis account. “Further support for the Tablet Theory comes from several additional facts,” Davis writes. Those facts are reproduced, in part, in the following list:

- In no instance is an event described that could not have been known by the person assigned to the [hypothetical] tablet.

- In all instances, the history of events in a tablet ceases before the death of the person assigned to the tablet.

- Within the 10 tablets of Genesis [quantified by Wiseman], the beginning of each tablet is usually followed by a brief repetition of a prominent feature of the preceding section. For example, Tablet 2 has Gen 2:7, repeating the creation of man. …

- Abraham, the most prominent figure in Genesis, does not have a tablet. This fact indicates that the toledot structure is something other than a breakdown based simply on a list of the main figures in the book.

‘Books’ of Our Fathers

Percy Wiseman’s theory is indeed intriguing, but must remain a theory until discoveries shed further light. Naturally, the merits of his theory have been debated over the decades. A chief source of support was his son, Prof. Donald J. Wiseman obe, who went on to become a renowned Assyriologist in his own right. Perhaps unsurprisingly, however, the allure of high criticism and skepticism inherent in the Documentary Hypothesis meant that it has continued as the popular theory in mainstream scholarly circles (not unlike Darwinism), more or less drowning out Wiseman’s more literalist, conservative theory. Yet additional archaeological discoveries, as well as a compounding of problems with the Documentary Hypothesis, have made it practically untenable.

Naturally, with Wiseman’s theory, there are several avenues of disagreement. Did all the “toledot” statements represent concluding colophons? Certainly this fits well with several—but not necessarily all. Therefore, were some instead used as introductory statements to the Genesis text that followed them, rather than for the text that preceded? Regardless of the remaining questions, it provides interesting answers relating to the earliest composition of the biblical account.

What is meant by a “book of the generations of Adam”? Was it just meant as an internal division for the biblical text itself? Why, then, is such toledot phraseology found with such repetition for this Genesis material—and not found ubiquitously elsewhere? Further, if these statements are simply intended to frame text relating to major biblical figures, why are some of the lesser figures included, while some of the most important (i.e. Abraham) are left out? And why is Esau mentioned twice?

What would a Book of the Generations of Adam and a Book of the Generations of the Heavens and the Earth have looked like? And could such texts have been available and utilized in some way by the earliest biblical forefathers prior to Moses?

Of course, no “tablet” containing such exact text has been found. Wiseman did note the discoveries already being made in his time of Babylonian cuneiform “Flood tablets” and “Creation tablets” dating back some 4,000 years with striking similarities to the biblical account (in some cases, even down to the same species of birds being released from the ark to check for dry land). Yet as Wiseman opined, “the biblical records are immeasurably superior to the Babylonian. The Bible account is simple in its ideas and irreproachable in its teaching about God, while the Babylonian tablets are complex and polytheistic.” He inferred that such biblical texts must not have been extruded from the Babylonian, but just the opposite—that the existing Sumerian, Babylonian and Assyrian texts were themselves the product of extrapolation and “corruption” of original source material.

He wrote:

[E]ven hostile critics admit that the records preserved to us in Genesis are pure and free from all those corruptions which penetrated into the Babylonian copies. This [early Genesis] account is so original that it does not bear a trace of any system of philosophy; yet it is so profound that it is capable of correcting philosophical systems. It is so ancient that it contains nothing that is merely nationalistic, neither Babylonian, Egyptian nor Jewish modes of thought find a place in it, for it was written before clans, or nations or philosophies originated. Thus it is the original, of which the other extant accounts are merely corrupted copies. Others incorporate their national philosophies in crude polytheistic and mythological form, while this is pure. Genesis chapter one is as primitive as man himself, the threshold of written history.

During the earliest formation of the Documentary Hypothesis, the suggestion of such early, original written material would have seemed impossible. This was part of the reason for initial attempts to explain that even Moses could not have written material contained within the Torah. Indeed, it was not truly realized just how early writing began in man’s history—something addressed at length by Wiseman based on the inscriptional discoveries going back over a thousand years prior to Moses.

But perhaps that should have been no surprise. After all, biblical reference to writing may be hinted at as early as Genesis 4:26, which can be translated as “then began men to read/publish the name of the Lord” (compare with Jeremiah 36:8 and 51:63 for the same use of the verb).

Perhaps it’s not outside of the bounds of possibility, then, for a Book of the Generations of Adam or Book of the Generations of the Heavens and the Earth to have been in circulation early on—texts later utilized, incorporated or alluded to by Moses in compiling the earliest material contained within the Hebrew Bible.