Paris—the city of lights and of love, of fine art and fine food. Millions of tourists annually visit the capital of France to ogle at some of the most famous monuments in the world. Among the most famous is the Louvre Museum. Many may know the Louvre as the home of some of the world’s most iconic artworks. But some may not realize that the Louvre is also a treasure-trove of biblical artifacts.

While visiting the Louvre in April, I spent some time searching through its aged hallways for biblical treasures. The fruits of this “treasure hunt” are in this article. This is by no means an exhaustive list—but it represents a selection of some of the more prominent ones.

The Code of Hammurabi

The Code of Hammurabi is a black basalt stele from Babylon, just over 2 meters tall. Hammurabi was one of the most powerful and influential kings of the First Babylonian Dynasty, whose reign is generally dated somewhere within the 19th or 18th century b.c.e.

This stele, found in Susa in 1901, is designed in resemblance of a finger. The top of the stele depicts Hammurabi consulting Shamash, the god of wisdom, who is seated on a throne. The rest of the stele is etched with 282 laws Hammurabi established for his empire (which ultimately included most of Mesopotamia). Britannica calls the Code of Hammurabi “the most complete and perfect extant collection of Babylonian laws” ever found.

Many of Hammurabi’s laws parallel those of the Torah. Notice the following:

- Law 196: If a man put out the eye of another man, his eye shall be put out.

- Law 197: If he break another man’s bone, his bone shall be broken.

- Law 200: If a man knock out the teeth of his equal, his teeth shall be knocked out.

Compare this with Exodus 21:23-25: “[I]f any harm follow, then thou shalt give life for life, eye for eye, tooth for tooth, hand for hand, foot for foot, burning for burning, wound for wound, stripe for stripe.”

Some have postulated that the Code of Hammurabi may have served as inspiration for the adoption of the Mosaic laws contained within the Torah. How else to explain such similarities?

There is another explanation: The Bible states that the patriarch Abraham came from the city of Ur in Babylonia (Genesis 11:31; Hammurabi specifically lists Ur as a city in his realm in the code’s preamble). God states Abraham obeyed “My commandments, My statutes, and My laws” (Genesis 26:5), the same laws later recorded by Moses. First-century c.e. Jewish historian Josephus wrote in his Antiquities of the Jews that Abraham was “a person of great sagacity, both for understanding all things and persuading his hearers.” Josephus specifically listed Abraham as teaching people in Mesopotamia.

Could Abraham have influenced Babylon’s legal system?

As an aside, Hammurabi himself may even be mentioned in the Bible—as a contemporary of Abraham. Genesis 14:1 speaks of “Amraphel king of Shinar [Babylonia]” as a powerful ruler whose troops were part of a coalition that Abraham warred against. A literal transliteration of the Hebrew renders Amraphel as ‘amrāp̄el. Hammurabi’s name, in Akkadian (the language of the region), can also be translated as Ammurapi (and there is a later, divine form of the name, as Ammurapi-ili). Amraphel and Hammurabi thus may well be the same person—more on this subject can be read in our article here.

The Royal Palace of Susa

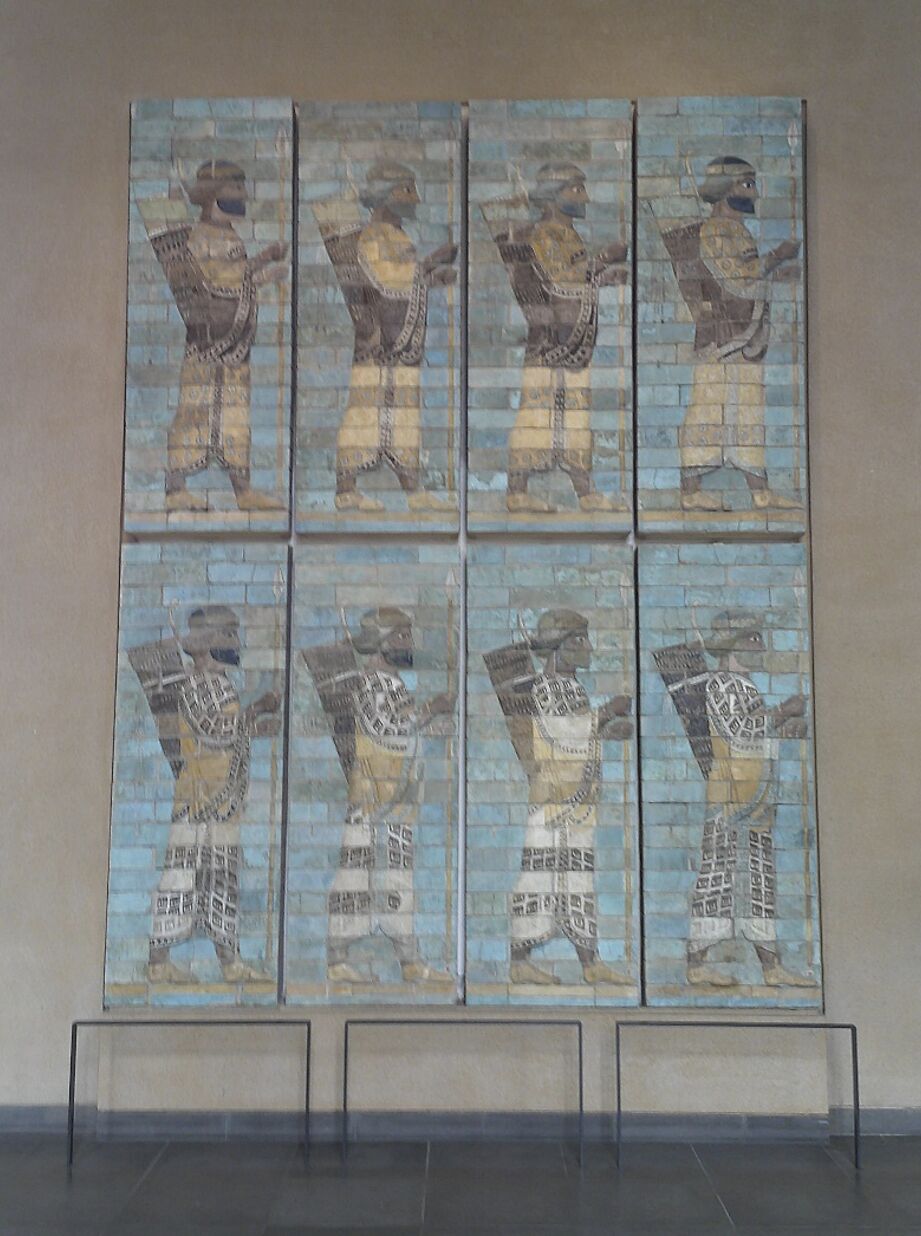

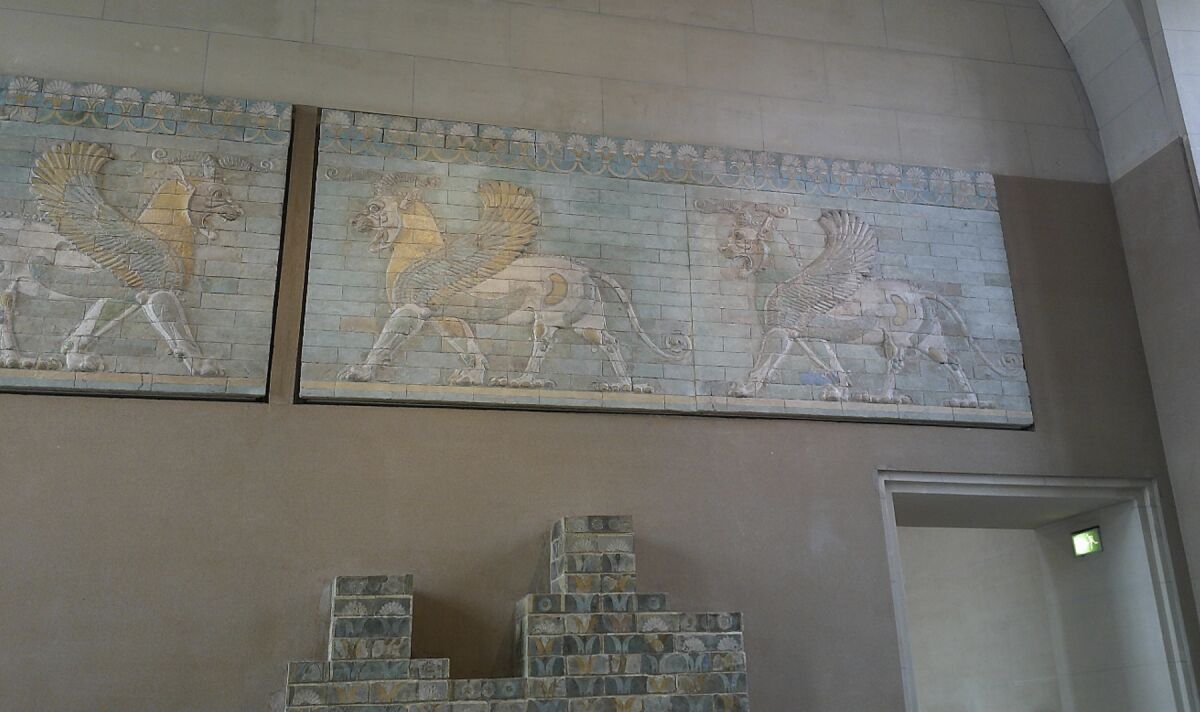

We now jump from one of Louvre’s earliest biblical artifacts to one of its latest. The ancient city of Susa (referred to in the Bible as Shushan) was one of the capitals of the Persian Empire and was excavated by the French in the 19th and 20th centuries. The Louvre houses some of the furnishings that decorated the Persian royal palace. The palace was built by King Darius i (who reigned from 522 to 486 b.c.e). Darius is mentioned in Ezra 5 and 6 as assisting the Jews in rebuilding Jerusalem’s Temple.

Among the artifacts from this period at the Louvre are some beautiful wall pieces depicting Persian soldiers and mythological creatures.

One of the most significant finds from the palace of Susa is a massive column capital shaped like a bull. At an already large height of 5.3 meters, it is estimated that the intact column would have stood about 21 meters tall. These massive columns were meant to support massive structures. This particular column was from the apadana, or audience hall, of the palace.

This could have been the very same room where Darius’s son Xerxes (the biblical Ahasuerus, reigning from 486 to 465 b.c.e.) held the infamous banquet where he had a spat with his queen, Vashti (Esther 1:1-12). Those events eventually led to the biblical heroine Esther becoming queen of Persia.

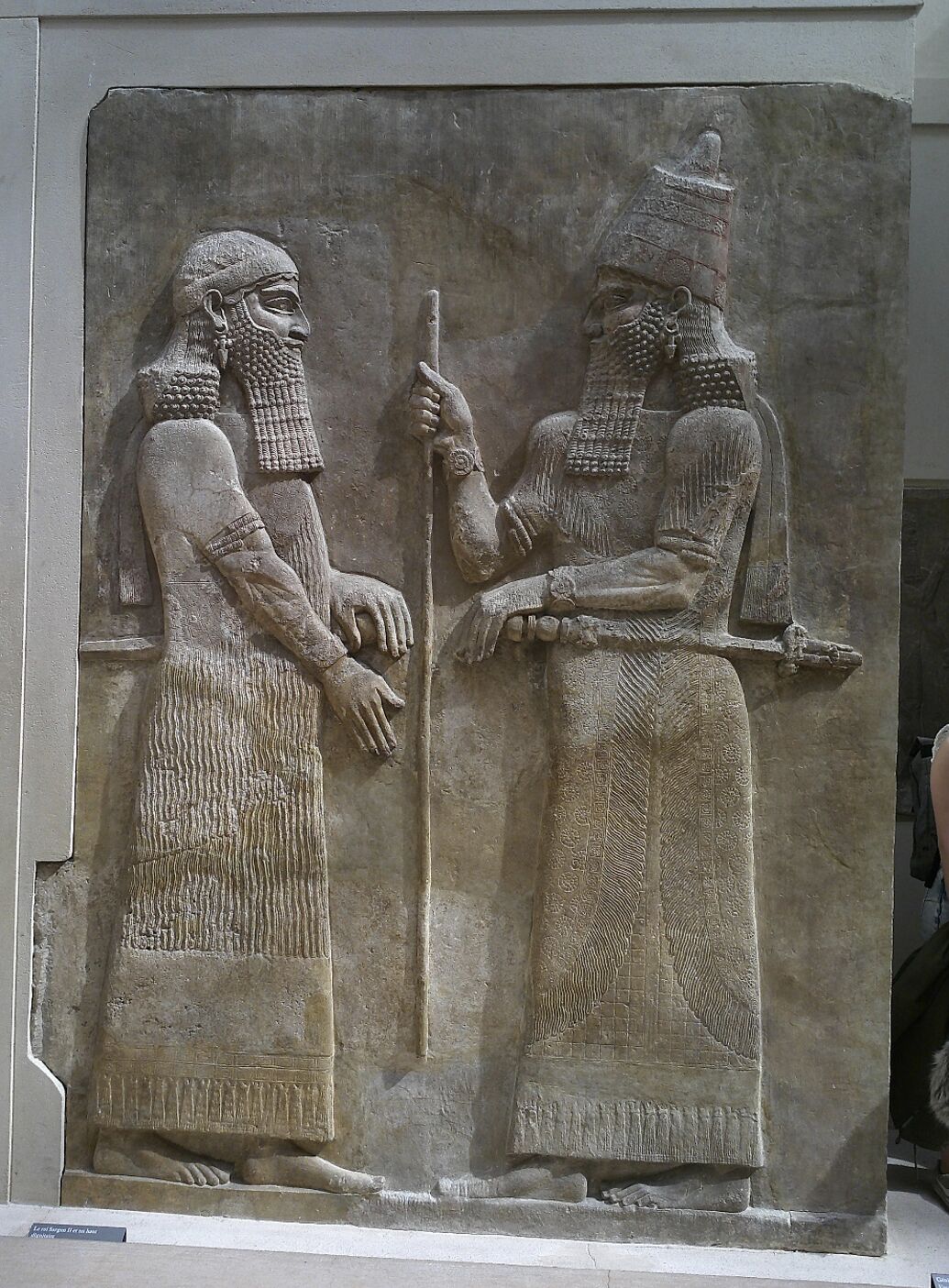

Sargon’s Palace

The palace at Susa was not the only ancient palace excavated by French archaeologists. They also excavated the palace at Khorsabad in northern Iraq. Known as Dur-Sharrukin in ancient times, this was the capital of Sargon ii, King of Assyria (722–705 b.c.e.). Sargon, mentioned in Isaiah 20:1, was the king who conquered Israel and sent the Israelites into Assyrian captivity in the years 721–718 b.c.e. (as recorded in his annals; see also 2 Kings 17:6).

The Louvre holds several artifacts from these expeditions. Below is a lamassu, an Assyrian sphinx that originally guarded the entrance of a building. (Note the depiction of five legs, as can be seen from this angle: This is to give a correct representation of four legs striding when viewed from the side, and two legs at attention when viewed from the front.)

The wall relief to the left depicts Sargon himself (right, wearing the crown of Assyria). The individual to his left may be his son and successor, Sennacherib. Sennacherib is mentioned prominently in the Bible as the Assyrian king who faced off against Judah’s King Hezekiah (see 2 Kings 18-19).

The wall relief below shows boatmen carrying cedars of Lebanon down the Euphrates River to Assyria. Cedar of Lebanon was a prized construction material, mentioned numerous times throughout the Bible. Solomon used cedars of Lebanon to construct the temple in Jerusalem (1 Kings 6).

The Phoenicians

France colonized Lebanon and Syria after World War i—so it comes as no surprise that the Louvre has an extensive collection of artifacts from the area. This includes many artifacts from the Phoenicians, the ancient inhabitants of the region. The Phoenicians were a seafaring people living just north of the land of Israel who interacted with the Israelites throughout biblical history. We’ll mention two specific Phoenician artifacts from the Louvre’s wider collection.

One of them is a relief discovered in Arwad, a city in coastal Syria (pictured right). It is 61 centimeters tall, and probably served as part of a door frame. Carved from marble, the top of the relief features an intricate palm design. At its center is depicted a sphinx—a mythological part-man, part-lion, part-eagle creature. This noteworthy Phoenician motif has parallels to a more famous biblical artifact: the Jezebel seal.

The Jezebel seal is an unprovenanced seal discovered in 1964 in a private collection that bears the name of the infamous Queen Jezebel, the Phoenician wife of the wicked King Ahab (1 Kings 16:31). Prominently featured on the seal is a sphinx with similarities to the one depicted here. Ahab and Jezebel are dated to have reigned in the ninth century b.c.e.—roughly the same time frame as this relief. These artifacts show Phoenician stylistic consistency, with a link to Egypt, during this period.

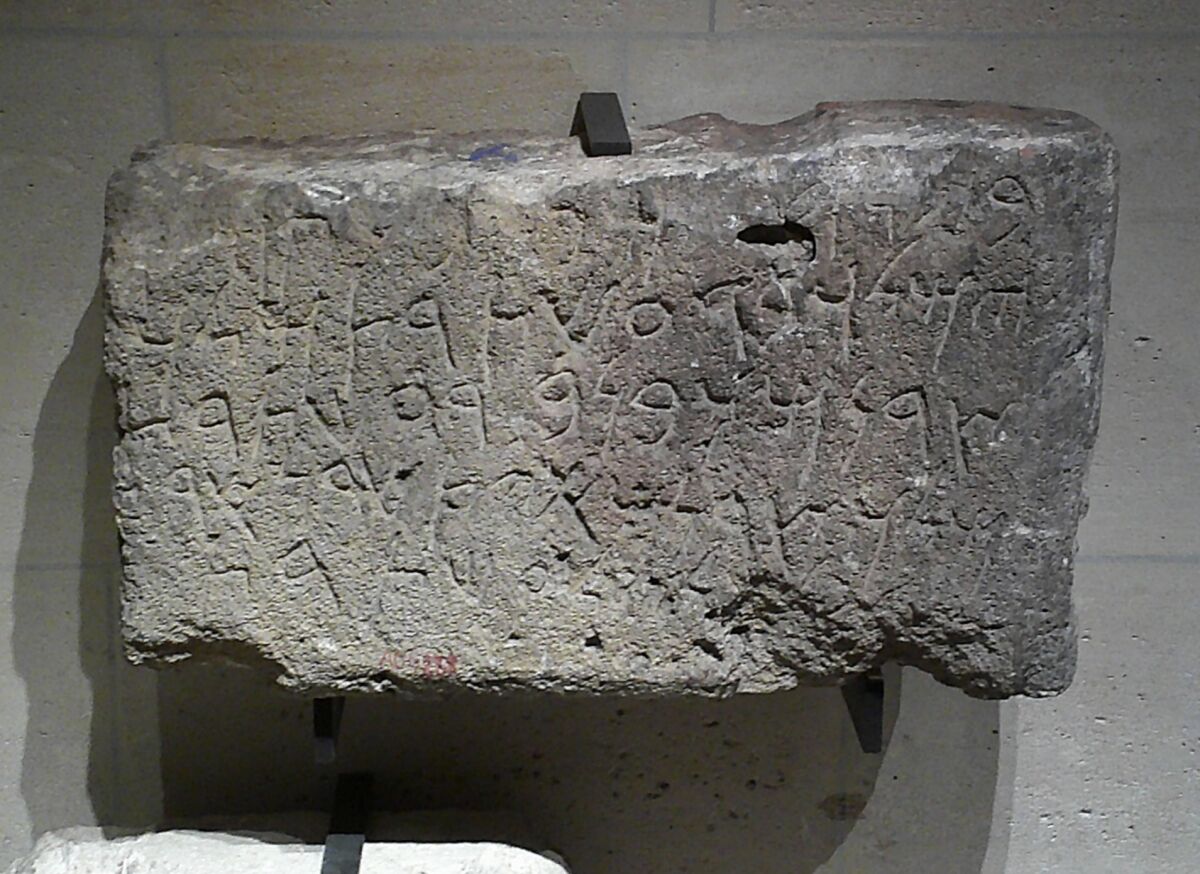

Another noteworthy artifact in the Louvre’s Phoenician collection is the Bodashtart inscription, below.

There are actually several such “Bodashtart inscriptions” owned by the Louvre. Bodashtart was the king of Sidon (otherwise spelled Zidon), a Phoenician city-state in modern Lebanon. A vassal of the Persian Empire, Bodashtart reigned in the late sixth century b.c.e. This particular inscription is a dedication by Bodashtart to Astarte, the goddess of fertility (known by a wide variety of names, including Ishtar and Ashtoreth).

Astarte was a pagan goddess the Israelites often entangled themselves in the worship of (Judges 2:13; 10:6; 1 Samuel 7:3). 1 Kings 11 shows that Ashtoreth was one of the pagan deities King Solomon went after in later years, incurring God’s wrath (verse 9). This was to accommodate his Sidonian wives (verse 1). Verse 5 specifically lists Ashtoreth as “the goddess of the Zidonians.”

Ezra 3:7 also states that when the Persian King Cyrus allowed the Jews to return from Babylon to Jerusalem to build the Second Temple, the Jews hired laborers “of Zidon” to import cedars of Lebanon for the Temple’s construction. Bodashtart, or one of his predecessors, could have been the king of Sidon at that time.

The Mesha Stele

The Mesha Stele is one of the most important and famous biblical artifacts in the Louvre’s possession. Also known as the Moabite Stone, it was first discovered by an Anglican missionary in 1868 in Dhiban, Jordan. The news of its discovery set Britain, France and Germany in a competition to acquire it. In 1869, Charles Clermont-Ganneau, an archaeologist and diplomat with France’s Jerusalem consulate, sent intermediaries to make a “squeeze,” a papier-mâché copy of the artifact. However, while the squeeze was drying, Clermont-Ganneau’s envoys got into a fight with local Bedouins. Not too long after, the Bedouins destroyed the stele into many fragments.

Clermont-Ganneau tracked down roughly two thirds of the fragments and reconstructed the rest based off of his squeeze. The reconstructed stele eventually ended up in the Louvre.

Why is it so important?

The inscription was commissioned by Mesha, King of Moab. Here is an excerpt from the text:

I am Mesha, son of Chemosh-melek, the king of Moab, the man of the Dibon [Dhiban’s ancient name]. My father reigned over Moab thirty years, and I sat on the throne after my father. And built a high place for Chemosh [a Moabite god—Numbers 21:29; 1 Kings 11:7] in Korha, a place of salvation for Mesha. For he hath delivered me from all monarchs, and he hath let me look with scorn upon all mine enemies. Now Omri was king over Israel, and he oppressed Moab for many days, for that Chemosh was wroth with the land. His son [King Ahab] reigned in his stead, and he said, ‘I will oppress Moab.’ Thus spake he even in my days; but I have gained the victory over him and over his house, and Israel is laid waste for ever.

Omri was one of the most influential kings of the northern kingdom of Israel. It was under him that Israel developed a new capital in Samaria (1 Kings 16:23-24). The Bible doesn’t give many details about Omri’s life. But it does say that he was a former military commander under his predecessor, Baasa/Baasha, and won a civil war for the throne of Israel (1 Kings 16:11-22). So Omri was a military man.

Omri’s son and successor, Ahab continued to reign over the territory of Moab. And the Bible records that at the time of his death, a Moabite rebellion began, led by king Mesha. “Now Mesha king of Moab was a sheep-master; and he rendered unto the king of Israel the wool of a hundred thousand lambs, and of a hundred thousand rams. But it came to pass, when Ahab was dead, that the king of Moab rebelled against the king of Israel” (2 Kings 3:4-5).

Here is another excerpt from the Mesha Stele: “The people of Gad [one of the Israelite tribes] had dwelt in the land of Ataroth from days of old, and the king of Israel built the city of Ataroth. And I assaulted the city and I slew all the people in the sight of Chemosh and Moab.” Ataroth was located on the east side of the Jordan River. Numbers 32:34 states that when the Israelites arrived in the Promised Land, the “children of Gad built Dibon, and Ataroth.”

Additionally important is the Mesha Stele’s reference to the God of the Bible. Line 18 of the stele reads: “I carried away from thence the [shrines] of yhwh, and dragged them on the ground before the face of Chemosh.”

Line 31 has another potentially explosive reference. There is some dispute as to the reconstruction of this section, as it is significantly damaged. But one phrase can be translated as “House of David,” in reference to the famous biblical king. There is one letter of David’s name damaged in the text, so the translation isn’t completely certain. However, many scholars find the attribution to David likely, and there is new up-close research of the stele bolstering this conclusion. This would make the Mesha Stele one of only one or two other artifacts naming the biblical king.

The Proof de la Bible

If one were to ask you where you could go to scientifically prove the Bible’s accuracy, the Louvre may not have been your first choice. The museum is more renowned for famous Greek statues and Leonardo da Vinci paintings. But it is also a treasure-trove of biblical artifacts. A visitor just has to know where to look.

Artifacts like the Code of Hammurabi or the Mesha Stele are much more significant than the museum’s other displays. The Louvre has many paintings that are beautiful to look at. But artifacts like the ones mentioned relate to the veracity of the most influential book ever written. It can make the Bible—the text billions of people worldwide claim as their heritage—come alive like never before. The tourist hordes may visit to swarm around the Mona Lisa or the Venus de Milo. But the real treasures of the Louvre are in their Near Eastern archaeology wings.

And the next time you’re in Paris, you can see them for yourself.