The patriarch Abraham is famous as the progenitor of the three great monotheistic religions on Earth: Judaism, Christianity and Islam. Though his name is common in antiquity (particularly during the late second millennium b.c.e., just following his lifetime), contemporary evidence directly naming this nomadic individual who lived nearly 4,000 years ago has remained elusive. Still, classical evidence abounds, and contemporary archaeological evidence has corroborated much of the biblical Abrahamic setting—from the geopolitical scene of various wars and alliances to local customs and traditions to certain names, prices and even sayings.

But could the father of Abraham—Terah, patriarch of the Moabites, Ammonites, Midianites, Ishmaelites, Israelites, Edomites and more—have been discovered? Some fascinating contemporary evidence describes a man that closely fits the biblical account—in name, location, dating and (rather unusual) story.

Ur … Where?

“And Terah lived seventy years, and begot Abram, Nahor, and Haran. … And Terah took Abram his son, and Lot the son of Haran, his son’s son, and Sarai his daughter-in-law, his son Abram’s wife; and they went forth with them from Ur of the Chaldees, to go into the land of Canaan; and they came unto Haran, and dwelt there” (Genesis 11:26, 31).

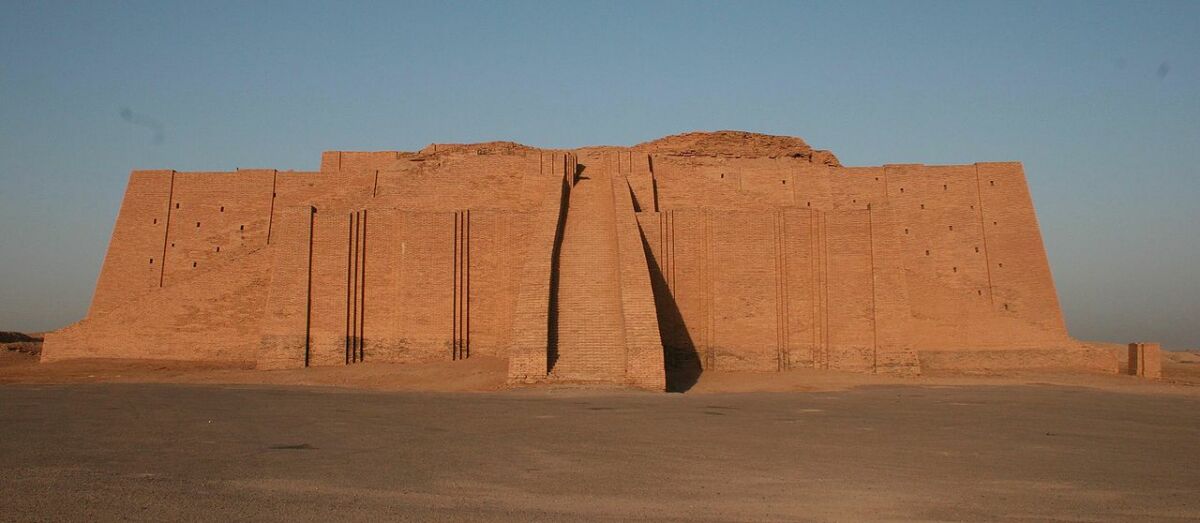

Before establishing the identity of the individual, we must establish where to look—“the land of his nativity, in Ur of the Chaldees” (verse 28). This most popularly is related to the famous Sumerian city-state Ur, containing a massive ziggurat, near the shore of the Persian Gulf in southwest Mesopotamia.

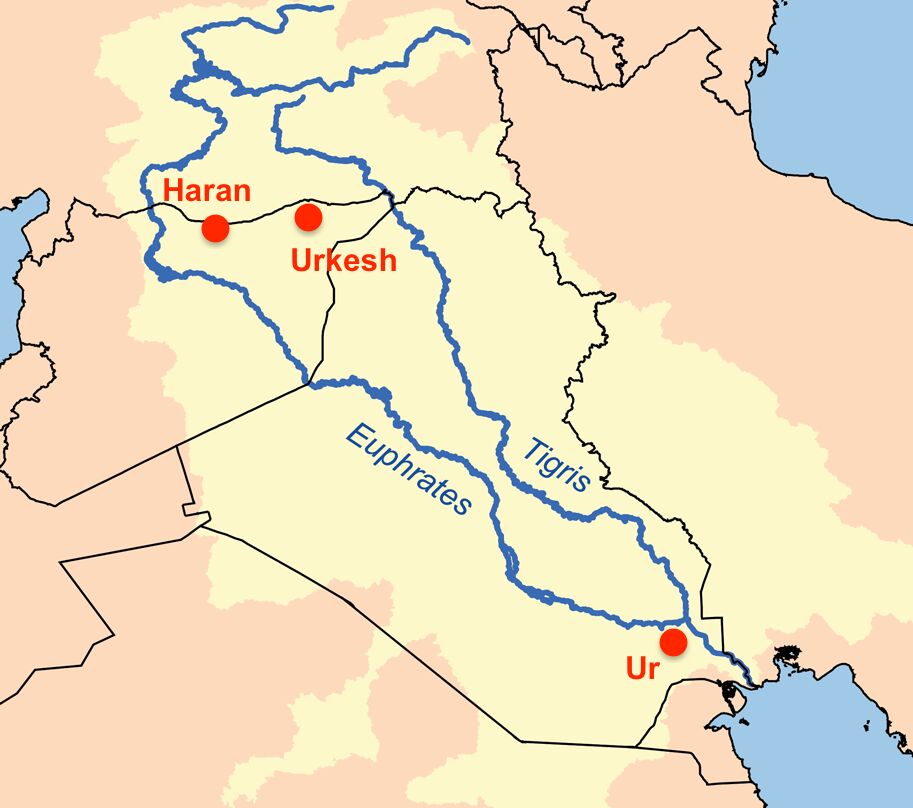

This site was excavated and named by the famous archaeologist Sir Leonard Woolley in the 1920s. But it is far from being the established location of Abraham and Terah’s “Ur of the Chaldees.” In fact, a long-standing position (held by influential ancient historians such as Josephus and Maimonides) has been that the city was located in northern Mesopotamia, in or around the modern-day border of Turkey. Proposed locations in this geographical region include Urartu, Urfa and Urkesh. The New Testament likewise affirms that Ur of the Chaldees was in “Mesopotamia” (Acts 7:2-3). The name Mesopotamia technically refers to the territory between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, primarily the northern part of the Fertile Crescent. The Sumerian Ur sits just outside, and south, of these rivers—not within.

The book of Joshua gives detail for the location specifically of Terah’s dwelling, in relation to the river system: “… Your fathers dwelt of old time beyond the River, even Terah, the father of Abraham, and the father of Nahor; and they served other gods. And I took your father Abraham from beyond the River, and led him throughout all the land of Canaan …” (Joshua 24:2-3). The context and commentaries make clear that this is referring to the river, the Euphrates. But the Ur of Sumer is technically on the same side of the Euphrates as Canaan is.

Further, the appellation “Ur of the Chaldees” could imply that there was another Ur, a city likely more significant (the Ur—the great Ur of Sumer?), that it was not to be confused with. And Abraham is also associated in classical literature with the territory of Assyria, which was in the north.

Genesis 11:31 states that Terah, Abram, Lot and Sarai “went forth with them from Ur of the Chaldees, to go into the land of Canaan; and they came unto Haran, and dwelt there.” Haran is well out of the way to Canaan, when travelling from the Sumerian Ur. But it is en route from the northern “Ur” options.

So which of the northern, “beyond the River”-Ur options is the best fit? Urartu wasn’t established until a millennium after Abraham. Urfa is a possibility. But Urkesh is also a good fit—and even moreso in name. “Ur of the Chaldees” is not a transliteration of the original Hebrew. The Hebrew title is Ur Kasdim (“im” is simply a Hebrew plural ending). Thus, a parallel between Urkesh—more properly titled in inscriptions Urkeš.Ki, and the biblical Ur Kasd[im].

As for our biblical “Terah”?

Terru, ‘Man of Urkesh’

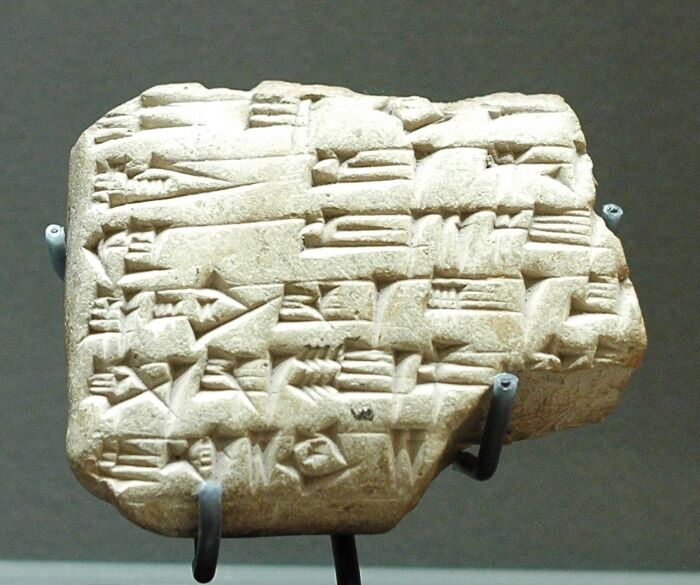

In the 19th century b.c.e., a prominent official appears in Urkesh, named Terru. What we know about Terru comes from a handful of cuneiform tablets sent to Zimri-Lim, king of Mari—some from Terru himself, and others referencing him.

Based on the correspondence, Terru is generally assumed to be some sort of kingly figure. However, he is never referred to with the typical title “king” of the time. In third-party correspondence, he is referred to simply as “the man of Urkesh.” In his own letters to Zimri-Lim, he refers to himself as “your servant.” This prominent, yet not necessarily kingly, position may be hinted at in the biblical account of Terah (i.e. Genesis 11:26-32; Joshua 24:2). And letters relating to Terru reveal a general “independence” of the Urkesh public.

More than that, they actually indicate a general public hatred for him. His letters to Zimri-Lim reveal that the Hurrian population did not accept him, and the correspondence speaks of hostility and resentment. “Because I have cast my lot with my lord, people in my town hate me. A couple of times I have had to save myself, escaping death” (arm 28 44bis).

“They do not speak with me,” Terru lamented to Zimri-Lim in the Mari correspondence. “They speak evil things.” One of Zimri-Lim’s replies follow: “I did not know that the sons of your city hate you on my account. But you are mine, even if the city of Urkesh is not.” The inference is that Zimri-Lim had set up Terru as a regional representative in “your [his] city.”

This public scorn for Terru also parallels the patriarch Terah. The Bible does not give any specific details, but hints at an incredibly tragic series of events. It mentions Haran mysteriously dying “in the presence of his father” (Genesis 11:28) at Ur Kasdim, and that Terah subsequently left the city, taking most of his extended family away with him to a distant location also called Haran (verse 31).

Later classical accounts suggest that Haran was killed by the city’s inhabitants, who hated him and his brother Abraham for their stand against idol worship. Their father Terah, however, had been an idol-worshiper himself (Joshua 24:2)—the circa 400 c.e. Midrash Genesis Rabbah states that he was an astrologer and seller of idols. The first-century historian Josephus wrote that, following the death of his son, “Now Terah hating Chaldea, on account of his mourning for Haran, they all removed to Haran of Mesopotamia” (Antiquities, 1.6.5). Josephus did not give details of Haran’s death, but he related that Abraham personally adopted Haran’s son Lot (hence the close connection between the two in the Bible). Perhaps there was some feeling of responsibility in this; after all, Jewish tradition relates that the primary anger of the pagan city was for Abraham, and that Haran, in following his brother’s lead, had thus been killed. Of Abraham’s early preaching, Josephus wrote that “for which doctrines … the Chaldeans and other people of Mesopotamia raised a tumult against him” (Antiquities, 1.7.1). This would certainly explain a public “hatred” for their father Terah.

Nahor, brother to Abraham and Haran, initially stayed behind in the land (Genesis 11:31). It seems Nahor’s family remained partial to idol worship (Genesis 24:15, 29; 31:30), while Terah seems to have repented in departing “for Canaan” with Abraham. There is a sense of coming full circle with the Genesis 11 account of Terah: the tragedy of a son dying young in the presence of his father—and finally, Terah himself dying in Haran (the territory). Perhaps there was a degree of guilt felt on the part of Terah for what had happened to Haran.

The classical historical accounts of Ur Kasdim’s idol-worshiping population, hateful toward Terah’s family, could fit well alongside the hated-yet-prominent leader of Urkesh, Terru. (And perhaps it is no coincidence that Terru is associated with another prominent younger leader in Urkesh, Haziran—could this be a link to Terah’s son, Haran?)

And perhaps it is likewise no coincidence that many of the peculiar biblical Abrahamic customs and laws can be traced back to this Hurrian region, within which Urkesh was situated. There was also a known early Habiru contingent at Urkesh—the Habiru are often associated with the Hebrews, based on their parallel 14th-century b.c.e. “conquest” of Canaan. Abraham is named early on in the Bible as “the Hebrew” (Genesis 14:13), a title generally considered to apply to descendants of the earlier patriarch Eber (Genesis 11:14).

As for the dating: There is some debate about chronology regarding the early second-millennium Mesopotamian ruler (with Low, Middle and High chronologies, varying up to about 120 years on either end). Certain chronological Bible verses point to Terah being on the scene in the 20th–19th centuries b.c.e., which fits well with the High Chronology placement of Terru. Further, the period in which Terru lived was just prior to a remarkable Mesopotamian period that fits with the early biblical account of Abraham in Canaan—even fitting with the names of Mesopotamian rulers that he warred against! This is the infamous period of Hammurabi, which again parallels the Bible along a High Chronology timeline. (Read more about this in detail here.)

So was the “hated” Terru, “man of Urkesh,” one and the same as the tragic biblical Terah, man of “Ur Kasdim”? That’s for you to decide. Besides the above limited inscriptional evidence, very little is known about Terru and Haziran.

Numerous archaeological discoveries have attested to the biblical events of the time of Israel’s kings. Typically though, the earlier the period, the more piecemeal the evidence. Still, there is a multitude of evidence for the pre-monarchy period—the time of the judges, the Israelite sojourn in Egypt, even the period of the patriarchs: remarkable evidence for customs, practices, prices and sayings—alongside the individuals themselves!

Times of Israel blog writer Samuel Griswold wrote about the Terah-Terru connection in his article “Urkesh: Abraham’s Ur of the Chaldees?” He concluded: “Other than for historical accuracy, why is this important? How can it inspire us as Jews today?” It’s a great question. He continued: “I feel it gives a context for greater understanding of the culture that Judaism developed ….”

In relation to the focus of this article specifically, though: The story of Terah is one of tragedy—but it ultimately becomes a supremely inspiring one. From wayward beginnings in an oppressive environment, Terah’s son Abraham grew up to became one of the most prominent individuals of the Bible, praised in its pages like none other; held in more worldwide esteem than almost any other individual in human history; venerated by Jew, Christian, Muslim (and even ancient Greek); equally respected by mortal enemies, by radicals and moderates, by both sides of sectarian divides; a son whose name to this day is used as a byword for the possibility for peace in the Middle East; a man in whom, according to the Bible, “shall all families of the earth be blessed”—a man known as the “father of the faithful,” the “friend of God.”

That would make a father proud.