If everybody’s doing it, that makes it OK. Well, no. But that does make it a cultural universal—the anthropological name for something done, in some form or other, by every human culture around the world. This includes language, religion, music, art, war, families, gender roles, laws, taboos, personal names, etiquette, morals, etc. The cultural universal can be somewhat of a pain for evolutionists to try to explain. In a world where societies are supposed to have migrated and evolved and changed and developed and faced various extinctions so separately, how could it be that every culture does these things?

One difficult cultural universal is marriage. In some form or other, it is found worldwide across all cultures. But why? It’s certainly not necessary for reproduction. Where did such a seemingly abstract idea come from, and how did everyone end up doing it? How do the anthropologists explain it, according to the theory of evolution, and what does the Bible say? Does archaeology give us any leads as to what the earliest marriages looked like?

This is the first in a series of articles on cultural universals—examining and comparing the secular and biblical accounts of our most human characteristics.

Evolutionary Road of Marriage

The general evolutionary idea of marriage is as follows:

- 5 million to 1.8 million years ago: First humans live in forests, gathering fruit—mothers able to carry young while gathering. No marriage required.

- 1.8 million to 23,000 years ago: Climate warms, forests recede, humans live in savanna environment, hunting required. Babies born earlier due to meat-based diet, requiring more care from mothers. Offspring of males and females in a “married” relationship have highest likelihood of survival, where the male can hunt and the female can care for the young. “Marriages” last a few years before parents part ways and new families are formed.

- 23,000 years ago to present: Agricultural age—marriages continue, but since humans are tied to a fixed plot of land, they are less likely to separate, thus marriage becomes a permanent endeavor.

The above is a very basic summation of a typical evolutionary assessment of marriage. And it is 100 percent speculation. This argument essentially assumes that marriage is the result of climate change. It does not explain how marriage came into being—only that when it did come into being, it produced the highest survival rates for offspring. If marriage was such a key aspect of natural selection, why do we not see animals marrying? Baboons live in a savanna environment. Why haven’t we seen them unite in matrimony? The chimpanzees’ diet consists of around 10 percent meat. Is that not yet quite high enough to cause their offspring to be as helpless as human babies, and thus to necessitate marriage? Chimpanzees are our “closest cousins.” Yet they have nothing close to monogamy—it’s a mating free-for-all—and males in a group simply treat all the young as their own, as there is no real way to tell whose offspring is whose. Why do these and other great ape “cousins” of ours still live a degenerate, un-evolved, fruit-eating forest life? Wasn’t “climate change” supposed to have forced us all out into savanna environments, eating meat and “having” to marry one another? Why have they stayed in the forests for their entire 22 million years-long evolutionary journey? And how did all human cultures end up with some form of marriage? Perhaps some few separate cultures—but all of us?

What’s more, even in the most secluded, primitive cultures, marriage has been found to be not just a token arrangement, but a highly regulated institution. And due to the fact that worldwide marriage laws have been found to be so similar, the early anthropologists affirmed that the institution bore the mark of “deliberate design.” Of course, “deliberate design” is anathema to the modern-day anthropologist.

Biblical Road of Marriage

The biblical description of marriage is, of course, much different. In the second chapter of the Bible, the marriage institution is created. “Therefore shall a man … cleave unto his wife: and they shall be one flesh” (Genesis 2:24). The Bible states that God ordained marriage between the very first man and woman on Earth. It was to be the relationship within which children could properly grow and develop. It was to picture the relationship between God’s chosen people and Himself. Marriage, from the first human beings, became the standard established pattern for succeeding generations, whether they were righteous or evil (Genesis 4). Four married couples entered the ark (Genesis 6:18), and after the Flood, all human beings, stemming from these eight, thus carried with them some form of marriage tradition.

This, then, very plainly explains why all humans have some form of marriage. In fact, it generally explains all cultural universals—why we see all of these earth-wide, common behaviors and customs known as the human condition—they are evidence of a small, core group of humans from which all mankind descended.

The evolutionists hypothesize. Perhaps. Maybe. Possibly. Could be. The Bible states dogmatically: This is the way it is. Can we know for sure which is right?

What does archaeology have to say? Has putting spade to soil revealed any answers?

Early Marriages: Customs and Laws

According to the biblical account, the earliest marriage, between Adam and Eve, would have happened around 6,000 years ago. The earliest-discovered written evidence we have of marriage dates to around 4,500 years ago on several tablets discovered in the Near East. It is interesting that this is our earliest secular reference if humans really had been engaging in marriage (in some form or other) for hundreds of thousands of years prior.

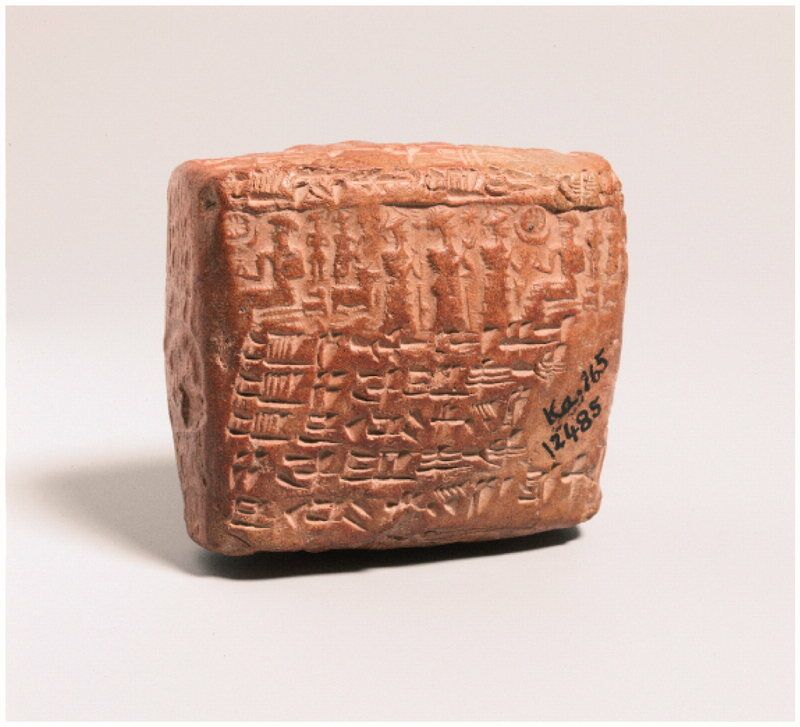

Cuneiform was the primary style of writing in ancient Mesopotamia. Quite literally hundreds of thousands of cuneiform tablets, around 2,000 to 5,000 years old, have been discovered in the Middle East. (The British Museum alone contains around 130,000 cuneiform tablets.) Many of these tablets discuss marriage, and several are official marriage contracts. However, it is believed that the very early Mesopotamian marriage contracts were conducted orally, because the contracts that have been discovered describe very specific familial circumstances. It seems that in the case of “normal” marriage, without any “baggage” so-to-speak, no written contract was necessary. This gradually changed as time went on; during the reign of Hammurabi (c. 1750 b.c.e.), a marriage was not valid unless it was written up contractually.

A fantastic coverage of ancient marital laws and customs can be found in Prof. Marten Stol’s book Women in the Ancient Near East. Several of the following points have been sourced from his publication. Due to the sheer number (thousands) of these marriage tablets, they will be, for the most part, only generally described in this article. More specifics can be found in Stol’s book. Nearly all of them date to the second millennium b.c.e. (2000 to 1000 b.c.e.), especially the earlier part.

From these early second-millennium Near Eastern tablets we learn that it was generally the parents who were involved in marital decisions; namely, in choosing a spouse. Typically, it was the woman’s father who made the decision to accept the marriage; next in line was the mother or brother. Brothers would quite often have a hand in making the decision of marriage for a sister. This can be seen in the marriage of Isaac and Rebekah, who would have been well familiar with these customs during their time period (Genesis 24). Abraham sent his servant to find a wife for his son Isaac. When the woman, Rebekah, had been found, it was her father Bethuel and her brother Laban who gave the final word of approval for Rebekah to marry Isaac (verses 49-51).

Dating to the period of the Middle Assyrian Empire (14th to 10th centuries b.c.e.), a contract was found allowing a suitor to live in a house for 10 years (food and clothing provided) and work to earn his bride. Another document attests that a man “served for seven years” to earn his bride. The biblical parallel to this is the patriarch Jacob, who contracted with Laban to work seven years in exchange for his daughter Rachel (Genesis 29—he served an additional seven years due to Laban’s deceit).

Nothing Personal—It’s Just Business (Sort Of)

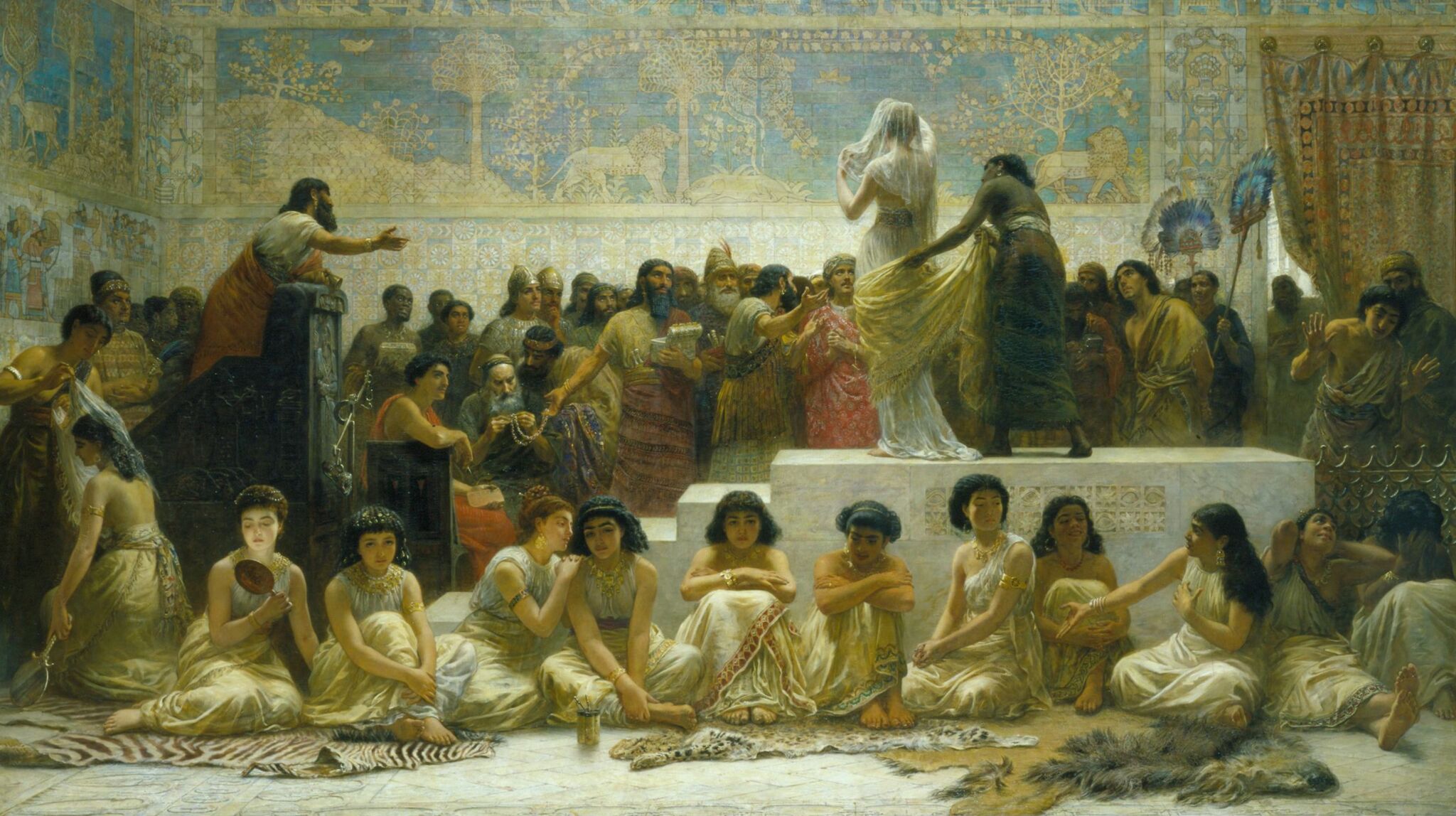

The common ancient way of negotiating a marriage was the “bride price.” Different women, depending on the circumstances, would have different prices. As loveless as it sounds, this was simply the custom of the day, and marriage was no whimsical decision—it required serious economic considerations for both households. It is from the Old Babylonian system (20th-16th centuries b.c.e.) that Abraham emerged. For them specifically, bride price was nearly always paid in silver (or at least calculated according to the value of silver).

In the first part of the second millennium, the going rate for a normal wife was around 10 shekels of silver. Around the time of Hammurabi (1750 b.c.e.), prices were going up, and the typical bride price was 20 to 30 shekels of silver.

There are a couple of interesting biblical descriptions of bride price. Several scriptures describe wives being paid for in silver. The Prophet Hosea was commanded to take an adulterous whore as a wife—for her, he paid 15 pieces of silver, along with some additional goods (Hosea 3:1-2—combined cost came to the equivalent of 30 shekels of silver). This account, though, was much later—around 750 b.c.e.

Before the time of Hammurabi, when a “normal” wife was going for around 10 to 20 shekels of silver, we find the biblical story of King Abimelech. This Philistine king mistakenly took to his harem Abraham’s wife, Sarah. God warned him to return her, and He cursed his entire household with childlessness (he may have held on to Sarah for quite a while in order for this curse to be realized). Abimelech gave Abraham 1,000 shekels of silver for the wrongdoing and returned Sarah. This massive reparation is the result of several factors: 1. Abimelech was a king; 2. Abraham was a highly regarded, princely figure; 3. God Himself had warned Abimelech and cursed his household.

According to Middle Assyrian laws (14th to 10th centuries b.c.e.), a rapist was to marry his victim, paying triple the value of silver as for a virgin. This penalty was likely applied to more simple acts of fornication as well. According to biblical laws given during this period, if a man seduced and fornicated with a woman, he was to pay the high price of 50 shekels of silver and marry her (Deuteronomy 22:28-29).

There are cases recorded where a man took advantage of selling off his daughter (oftentimes an adopted daughter or even a sister), and would retain the bride price entirely for himself, not turning anything over for her benefit (such as in the form of a dowry). This practice is literally translated as “eating the silver,” and it is directly referenced in the Bible. Rachel and Leah condemned their father Laban for this, and may well have stolen his idols (Genesis 31:19) for this very reason. Verses 14-15 (Christian Standard Bible) read:

Then Rachel and Leah answered him, “Do we have any portion or inheritance in our father’s family? Are we not regarded by him as outsiders? For he has sold us and has certainly spent our purchase price.”

“Spent our purchase price” is literally translated as “eaten our silver.”

Third-Party Surrogacy

An interesting tablet from Kültepe-Kanesh, Turkey, was recently discovered dating to Abraham’s time period (around 2000 b.c.e.). The tablet is a marriage contract, stating that if the couple cannot produce a child after two years, then a slave will be brought in as a surrogate mother to produce a male descendant for the husband and wife. The slave-mother was then to be set free after giving birth to a male.

The tablet’s parallels to the story of Hagar are unmistakable. Genesis 16:2 (King James Version) reads:

And Sarai said unto Abram, Behold now, the Lord hath restrained me from bearing: I pray thee, go in unto my maid; it may be that I may obtain children by her. And Abram hearkened to the voice of Sarai.

Clearly, God did not intend for Hagar to be taken in as a surrogate mother. Nor was it biblically lawful. This act, though, did have legal precedent. It would have been a practice Abraham and his wife were well familiar with—especially considering Abraham was a leading educator within the Babylonian community.

As the biblical account continues, after Hagar conceived and gave birth to a son, jealousy and discontentment became unbearable within the household. God instructed Abraham to release Hagar and Ishmael. Interestingly, according to the specific contract on the above tablet, the surrogate mother was to have been freed anyway after giving birth. Perhaps even the pagan Mesopotamian lawmakers had foreseen the potential for severe household conflict. Of course, had it all been done according to God’s purpose from the beginning, this domestic nightmare would never have occurred.

Laws and More Laws

There are several other Near Eastern marital laws discovered on tablets that have a direct correlation with those found in the Bible and date to roughly the same time periods. Not that many of these laws are right according to the Bible—only, that they were the accepted norms of the cultures at the time and are thus commentated on by the Bible.

There were laws allowing a man to take another wife if no children were born. There were laws enabling a man to take concubines. Divorce was acceptable under certain conditions, even if children were born. There were laws that a wife could be legally made a “sister” in order to have more rights (Abraham is documented twice claiming Sarah as his sister, and Isaac did the same with Rebekah).

The taking of a maidservant as an additional “wife” is a common refrain in ancient texts, hearkening to the stories of Abraham with Hagar, Jacob with Bilhah, and Jacob with Zilpah. Even attested legally is the fact that the wife would be the driving force for bringing a second wife into the family. In Abraham’s case, it was his wife Sarah who pushed Hagar toward him. In Jacob’s, it was his wives, Leah and Rachel, who brought their maids to him for relations—not the other way around.

In several cases, time limits were given for bearing children before marriage to a second wife was acceptable. Texts from Alalakh give the wife a period of seven years to bear children before the husband was allowed to take a second wife. This was likely the same concept taken up by the Prophet Samuel’s father, Elkanah. His favorite wife, Hannah, was childless, while his other wife, Peninnah, had many children. It is likely that Peninnah was brought on board later on after it was realized that Hannah could not bear children (1 Samuel 1).

Biblical levirate marriage involves a childless widow marrying the brother of her dead husband in order to raise up children for the dead husband’s name and to keep property within the family (Deuteronomy 25:5-10). Parallels of this ancient practice have been found during the same period (1500 to 1000 b.c.e.) among the Assyrians, Hittites and Hurrians.

Both men and women involved in adulterous relations in the Near East were put to death, as paralleled in the biblical account (Leviticus 20:10). According to King Hammurabi’s Code (c. 1750 b.c.e.), a rapist of a betrothed woman was to be put to death (as paralleled in Deuteronomy 22). A Hittite law states:

If a man should take a [married] woman in the mountains, it is the fault of the man and he is put to death. If, however, he takes her in the house, it is the fault of the woman; the woman is put to death.

This reads very similarly to Deuteronomy 22:23-27 (kjv):

If a damsel that is a virgin be betrothed unto an husband, and a man find her in the city, and lie with her; Then ye shall bring them both out unto the gate of that city, and ye shall stone them with stones that they die; the damsel, because she cried not, being in the city; and the man …. But if a man find a betrothed damsel in the field, and the man force her, and lie with her: then the man only that lay with her shall die … For he found her in the field, and the betrothed damsel cried, and there was none to save her.

Why This Matters

We have gone through just a smattering of parallel biblical and secular accounts of ancient marriage. The discovery of these numerous ancient tablets, specific particularly to the second millennium b.c.e., help verify the biblical appraisal of ancient marriages. Especially so, because they directly confirm marriage practices throughout the book of Genesis. According to many modern scholars and biblical minimalists, Genesis was not written until around 500 b.c.e.—1,000 years after its traditional, biblical date of authorship. But how were such late authors to so accurately describe marriage practices of the ancients? Many of the unique and specific early-second-millennium laws for marriage went out of effect in later centuries. How was the Bible to have represented these laws for just the right time period?

And here’s pause for thought: If the Bible is so contextually accurate regarding ancient marital practices, couldn’t it be accurate about the genesis of marriage itself?

The Bible has much to say on the history of marriage. And beyond that, it has much to say on the meaning and crucial necessity of marriage. It should give pause to those elements of modern-day Western civilization trying to do away with it.

Articles in This Series:

Marriage: A ‘Cultural Universal’ in Archaeology and the Bible

Language: A ‘Cultural Universal’ in Archaeology and the Bible

Clothing: A ‘Cultural Universal’ in Archaeology and the Bible