He mocked the Jews and laughed them to scorn. Governing the region just above Yehud, this man had a full view of the work going on in Judah. Perhaps best known as Nehemiah’s main adversary, he tried numerous times to stop Nehemiah in leading the nation to rebuild the wall around Jerusalem, which was finished remarkably in just 52 days! And as if persecution during his lifetime wasn’t enough, in an indirect way this governor also divided the high priest’s line in Judah, creating a schism that plagued the Jews for centuries.

This man is only mentioned in one book of the Bible—Nehemiah. But within that relatively short book are several instances where this governor of Samaria caused tremendous grief and obstacles for the Jews of Nehemiah’s time.

Sanballat was his name.

Yet his name is not exclusive to Nehemiah’s account. Let’s take a look at the ancient artifacts that bear his name and bring this ancient adversary to life—2,500 years later.

Sanballat—‘Sin Has Begotten’

First, let’s briefly cover the details surrounding this governor and the origin of his people, the Samaritans.

The name Sanballat comes from the Babylonian name Sinuballit, which means “Sin has begotten.” “Sin” was the Sumerian moon god of that time. This Samarian governor lived and reigned in the mid-to-late fifth century b.c.e. In the book of Nehemiah, Sanballat is called “Sanballat the Horonite.” Another possible translation of the word “Horonite” is Harranite. Harran was a prominent ancient city in Upper Mesopotamia, which today is located near the border between Turkey and Syria. The Horonites were likely among the series of different peoples transported to Samaria by the Assyrians around 718 b.c.e. to replace the deported Israelites.

In the century prior to Nehemiah’s governorship, Zerubbabel arrived in Yehud to rebuild the temple. The Samaritan people sought to join Zerubbabel and the Jews in their rebuilding (Ezra 4:2). In the Samaritans’ eyes, they kept the same religion as the Jews. In reality, however, the Samaritans were ethnically separate, and their religion was a mixture of paganized Israelite and Babylonian teachings (2 Kings 17). This is why Zerubbabel told the Samaritans, “Ye have nothing to do with us to build a house unto our God; but we ourselves together will build unto the Lord, the God of Israel …” (Ezra 4:3). This angered the Samaritans and the other surrounding districts, and they “weakened the hands of the people of Judah, and harried them while they were building, and hired counsellors against them, to frustrate their purpose …” (verses 4-5).

By the time of Nehemiah, Sanballat was governor of Samaria and a sworn enemy of the Jews.

In Nehemiah 2, Sanballat and two other governors laughed the Jews to scorn and despised their plan to build a wall (verse 19). Once construction began, Sanballat became very “wroth, and took great indignation, and mocked the Jews” (Nehemiah 3:33; 4:1). Sanballat’s last attempts to frustrate the work as the wall neared completion are recorded in Nehemiah 6. He even went as far as to hire an inside man to try to get Nehemiah to commit a sinful act in order to be banished by the Jews.

After governing Yehud for 12 years, Nehemiah returned to Persia to serve King Artaxerxes in 433 b.c.e. (Nehemiah 13:6). He did eventually return after an unspecified amount of time, but the Bible doesn’t state who ruled during this interlude in Nehemiah’s terms as governor.

While Nehemiah was away, Sanballat arranged for his daughter to marry Manasseh, the high priest’s grandson (verse 28). Once Nehemiah returned, he offered Manasseh the chance to break off his relationship with his foreign wife—but Manasseh refused, so he was banished from Yehud and went to Samaria. This played a crucial role in the formation of the Samaritan priesthood, with its own holy mountain, holy book and high priest.

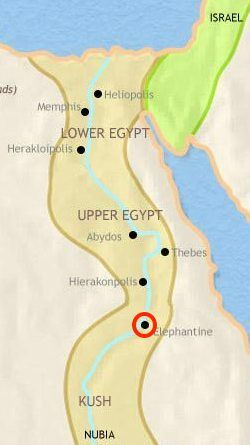

The Bible doesn’t say what happened to Sanballat after the wall was built; however, we are able to fill in the details. A collection of 175 ancient documents, known as the Elephantine Papyri, contains one in particular—the Elephantine Papyrus No. 30—that calls Sanballat by name and fills in some of the missing information of this interlude in Nehemiah’s account. Here’s a look at what the scientific evidence says.

The Elephantine Papyri

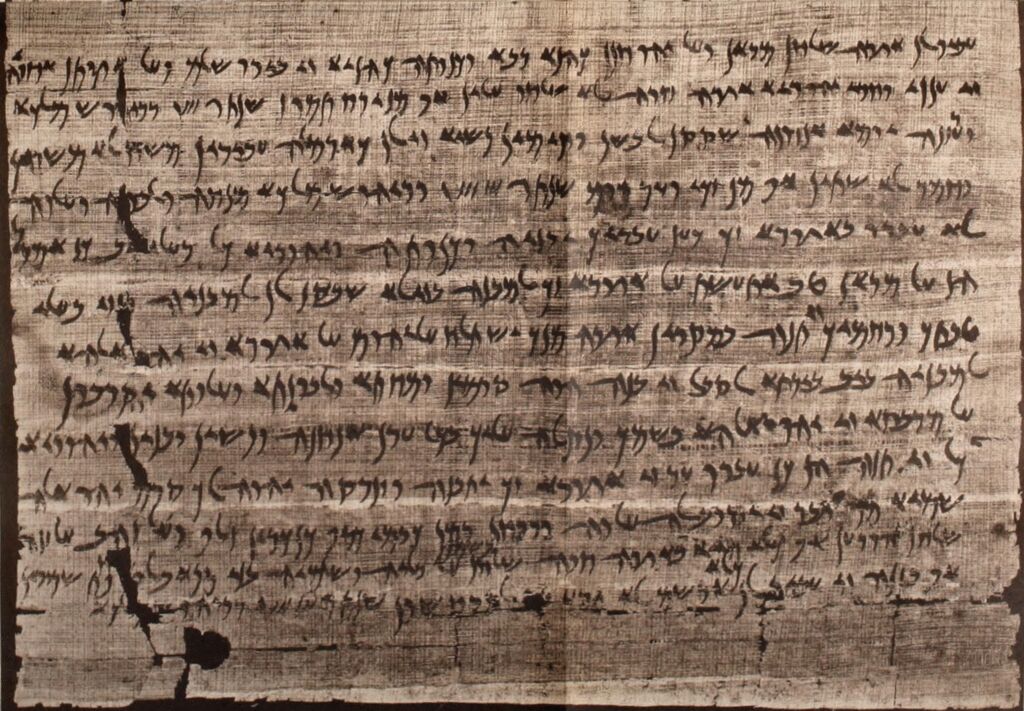

On Nov. 25, 407 b.c.e., the Jewish community from Elephantine in Egypt wrote a letter to Bigvai, the governor of Yehud at the time. This letter, or rather a draft or copy of it, was found among the collection of 175 documents in excavations in Elephantine in 1909. Papyrus No. 30 (also called the Elephantine Temple Papyrus, pictured below) contains 30 lines of inked Aramaic text.

After asking for permission to rebuild the destroyed temple at Elephantine, the letter states: “Moreover, all things in a letter we sent in our name to Delaiah and Shelemiah, sons of Sanballat, governor of Samaria.” The author apparently sent a copy of this same letter to these two sons of Sanballat. The letter’s mention of them seems to imply that they were acting on behalf of their aged father. However, since the letter says, “Sanballat, governor of Samaria” instead of “former governor,” we can deduce that Sanballat was most likely still alive at this point. Perhaps he was still ruling but his two sons were taking on part of his responsibilities.

Nehemiah mentions both Delaiah and Shelemiah in his account. Although these names cannot with certainty be linked to these two specific sons of Sanballat, they do attest to the prominence of such names during this time period.

In his publication Aramaic Papyri of the Fifth Century b.c., A. E. Cowley wrote, “The fact that the Jews of Elephantine applied also to Delaiah and Shelemiah at Samaria and mention this to the authorities at Jerusalem, shows that (at any rate as far as they knew) no religious schism had as yet taken place.”

And this matches the biblical account. Nehemiah records that the schism didn’t happen until his second term as governor. Nehemiah finished his first term as governor and returned to Artaxerxes in 433 b.c.e. This letter was written 26 years after Nehemiah went back to serve Artaxerxes. The Bible doesn’t indicate how long Nehemiah was away, so it’s possible that Nehemiah served Artaxerxes for this entire time before returning to Yehud—and the schism subsequently happened. However, if the letter was indeed written after the schism had already occurred, perhaps it was still recent enough that the full implications had not been felt yet, especially to this far-reaching colony.

Either way, the dating of this letter proves the veracity of Nehemiah’s account and the far-reaching influence of Sanballat and his sons as governing historical characters and contemporaries of Nehemiah.

The Samaria Papyri

Similar documents to the Elephantine Papyri were found in a cave at Wadi Daliyeh, 14 kilometers north of Jericho. In this cave, archaeologists discovered at least 18 Aramaic documents, 128 clay seals, several coins and the skeletal remains of 205 people. The artifacts date from the early to late 300s b.c.e. Most of the 18 papyri documents dealt with slave trades or other sales.

Based on the wealth discovered in the cave and the nature of the documents, some believe that these items belonged to the Samaritan governor’s family who likely fled when Alexander the Great invaded in 332 b.c.e. It’s likely that Alexander’s army pursued after these fleeing elite and executed them in this cave at Wadi Daliyeh.

Most significant to our study are two artifacts from this collection that feature the name “Sanballat.”

One artifact of special interest is a tiny clay bulla that reads: “…iah, son of […]ballat, governor of Samar[ia].” Since the dating of the papyri is during Artaxerxes iii’s reign, it is possible that this bulla is referring to a later Sanballat. But it is also plausible that this name belongs to the same Sanballat of Nehemiah’s account. The name ending “-iah” could fit with either of Sanballat’s sons mentioned in the Elephantine papyri: Delaiah or Shelemiah.

This collection of papyri includes a fragment of a papyrus that references “[…]ua, son of Sanballat (and) Hanan, the prefect.” The names Jeshua or Jaddua, later priestly figures listed in the book of Nehemiah, have been suggested as the missing name at the start of the inscription. The name Hanan, alongside Sanballat, is also found throughout the book of Nehemiah.

As the “archenemy” of Nehemiah, Sanballat caused the Jews a lot of grief during his reign. But conversely, his acts and prominence in the region serve as a help to the people of our day—providing artifacts that bear his name and prove his existence. Such artifacts continue to establish the veracity of the biblical account and help bring its pages back to vivid life.

For more information on the historicity of the book of Nehemiah, please read “Nehemiah: A Man and a Momentous Wall” as well as “Elephantine Papyrus: Proving the Book of Nehemiah.”