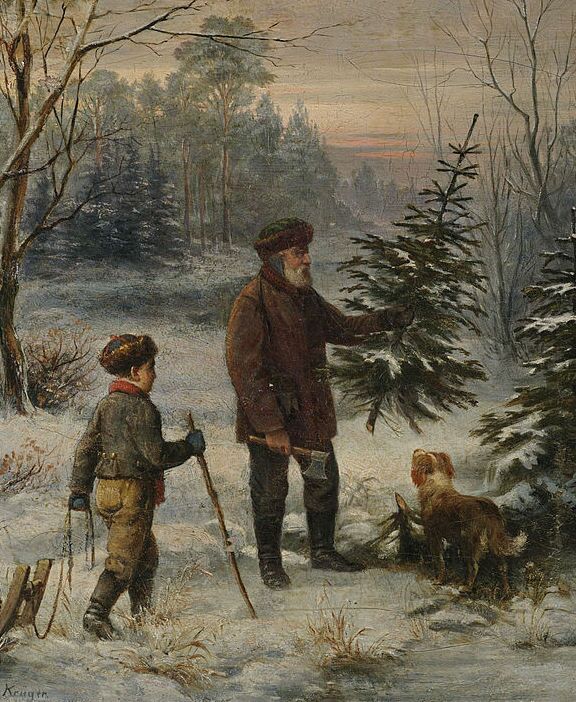

In most Western nations, this time of year is marked by an abundance of Christmas trees. Evergreens, the real deal or fake, are brought into homes, stores and places of worship and gilded with various decorations. Wrapped presents are placed under the branches. All in the name of Christianity—marking the birth of Jesus on December 25.

But did you know that there is no mention of Christmas trees—or even the date of Jesus’s birth—in the New Testament? Even more strangely: Did you know that the Old Testament, the Hebrew Bible, does contain scriptures that suspiciously appear match the description of Christmas trees? How could this be—many hundreds of years before Christianity?

The Hebrew Prophets on ‘Christmas Trees’?

The book of Jeremiah (written around 600 b.c.e.) states the following:

Hear ye the word which the Lord speaketh unto you, O house of Israel: Thus saith the Lord, Learn not the way of the heathen …. For the customs of the people are vain: for one cutteth a tree out of the forest, the work of the hands of the workman, with the axe. They deck it with silver and with gold; they fasten it with nails and with hammers, that it move not. They are upright as the palm tree …. (10:1–5; King James Version)

Here we see a tradition during the time of Jeremiah of cutting down a tree out of the forest, bringing it home, fastening it upright, and covering it with various silver and gold decorations. The tradition is identified here as a “heathen custom,” one that should not be “learned.”

The Prophet Isaiah, some 150 years earlier, uses some similar terminology in relation to trees, gold and silver:

The workman melteth a graven image, and the goldsmith spreadeth it over with gold, and casteth silver chains. He that is so impoverished that he hath no oblation chooseth a tree that will not rot; he seeketh unto him a cunning workman to prepare a graven image, that shall not be moved. (40:19–20; kjv)

This related account includes the interesting detail of spreading silver chains. From these passages, we also have some clues as to the type of tree featured in such rituals: Jeremiah tells us it is a forest tree, and Isaiah describes a “tree that will not rot.”

Eleven other passages throughout the Hebrew Bible—from the Torah all the way to the last book, Chronicles (according to the original ordering)—condemn “heathen” customs relating to green trees. Since most trees are, of course, green, the inference is apparent that these are evergreen trees. (The evergreen has long been a feature of worship, given its “eternal” life.)

Ten of those biblical passages condemn some form of idolatry occurring under those trees. “Enflaming yourselves with idols [often alternately translated as lust] under every green tree, slaying the children in the valleys …” (Isaiah 57:5; kjv). “Ye shall utterly destroy all the places, wherein the nations which ye shall possess served their gods … under every green tree” (Deuteronomy 12:2; kjv). “And they set them up images … under every green tree” (2 Kings 17:10; kjv).

Considering the accounts in the Hebrew Bible, alongside the fact that the New Testament says nothing even remotely related to the “Christmas tree,” where did the Christmas tree come from? And given the fact that the New Testament does not give any instruction for celebrating the birth of Jesus, nor even his birth date—in fact, certain verses makes clear that Jesus could not have been born on December 25 (more on that further down)—the broader question is: Where did Christmas celebrations actually come from?

Customs That ‘Long Antedate Christianity’

Encyclopedia Britannica states: “Christmas customs are an evolution from times that long antedate the Christian period—a descent from seasonal, pagan, religious and national practices, hedged about with legend and tradition” (15th edition; emphasis added throughout).

Naturally, such an allegation is likely to be met with surprise—or annoyance. “‘Tis the season to be jolly, and, perhaps, to have one’s social media inundated with memes about Christmas being nothing more than a co-opted pagan holiday,” Mary Farrow wrote for the Catholic News Agency. “Is there any truth to these claims? CNA spoke with several Catholic academics to find out” (article, “Is Christmas Simply a Re-Imagining of Ancient Pagan Celebrations?”).

Interestingly, the academics featured in Farrow’s article all expressed a level of support for this conclusion. Dr. Michael Barber noted that “there is some truth to the idea that Christians ‘baptize’ pagan ideas. … [T]here are also elements of the traditional Christmas celebration that are borrowed from pagan cultures. We are not quite sure how the tree, for example, became part of the Christmas scene but certainly there is nothing in Scripture that establishes it with Christmas.”

Dr. Mark Zia is quoted as stating that Catholicism “recognizes, appreciates, and incorporates into her own ‘Christian culture’ anything that is good, true, and beautiful, even if these things have their origins in pre-Christian religions or cultures.” And from Fr. Michael Witczak: “Even if December 25 as a date for the celebration of Christmas were taken from a pagan tradition … it does not negate the person of Christ. … [T]his dynamic of taking over things from a previous culture and then using it for Christian purposes … it’s kind of part and parcel of the way that the Church operates.”

Part and parcel indeed—as Prof. Andrew McGowen wrote in his Bible Review article, “How December 25 Became Christmas”: “A famous proponent of this practice was Pope Gregory the Great, who, in a letter written in 601 c.e. to a Christian missionary in Britain, recommended that local pagan temples not be destroyed but be converted into churches, and that pagan festivals be celebrated as feasts of Christian martyrs.”

In the rather flamboyant words of the famous televangelist Dr. Pat Robertson (in an extraordinary interview on cbn’s The 700 Club, below): “So, all this business about mistletoe? Pagan. Christmas trees? Pagan. Giving out gifts? Pagan. Every bit of it is pagan! Every single bit of it is pagan. We’ve Christianized it all. So that’s good, and so we have time that we celebrate for Jesus, and everybody gets all misty-eyed—but the truth is, they’re all pagan.”

On the flip side, it is interesting to observe that among some apologists who do attempt to dispute the “pagan origin” label for this holiday, the consistent theme is to try to explain at best why it is not pagan; not to explain why this—the most popular of all religious holidays—is biblical and holy. But perhaps this is unsurprising, given the total lack of mention of anything remotely resembling Christmas in the Bible—as opposed to the holy days that are commanded in Leviticus 23, which did continue to be kept by the early New Testament Christians. (For example, the Passover and Days of Unleavened Bread: Acts 20:6, 1 Corinthians 5:6–8; Pentecost: Acts 2:1, 20:16, 1 Corinthians 16:8; Atonement: Acts 27:9; the Feast of Tabernacles: Acts 18:21; compare also Zechariah 14:16–19.)

Bruce Shelley takes on this allegation of “paganism” in his Christianity Today article, “Is Christmas Pagan?” “Christians found ways to redeem local cultures and salvage those elements that naturally pointed to Christ,” he wrote. He actually continues to paint many of the other modern “Christian” celebrations with the same broad brush:

Was the event we now call Christmas originally a “pagan holiday”? In some ways. Does that mean the church should discard it, along with its lights, tinsel, and increasing commercialism? Only if we are prepared to abandon many other holidays and common Christian practices that the early church co-opted ….

All In the Art

Again, as asserted by Encyclopedia Britannica—a “descent from seasonal, pagan, religious and national practices.” But should such a revelation of overlaying Christian figures onto existing pagan ideas be a surprise? After all, this was precisely the practice carried out by early Christian artists—the well-attested practice, quite literally, of overlaying a biblical cast of characters onto pagan themes. (This is highlighted, for example, in Sarah Yeomans’ Biblical Archaeology Society article, “Borrowing From the Neighbors: Pagan Imagery in Christian Art.”)

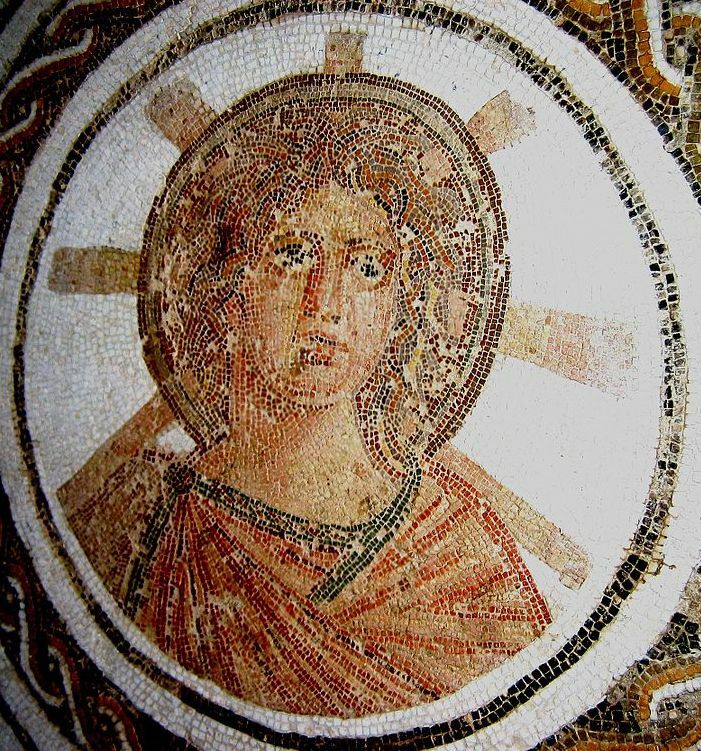

There is the classic portrayal of Jonah asleep under the vine, depicted in the style of Endymion sleeping under the goddess Selene. Pictures of “heaven” displayed in copycat style of the typical heavenly melee of pagan gods. Jesus portrayed in the style of the god Apollo and Helios. Both Jesus and David depicted as Orpheus. Images of the Roman boy-god Cupid appropriated as a Christian symbol of “love,” particularly prevalent on St. Valentine’s Day—despite the fact that early Christian authors considered him a demon of fornication. The “Madonna and Child,” in the style of Isis and Horus. The suspiciously similar dog-headed Saint Christopher and Egyptian god Anubis/Hermanubis (with suspiciously similar saint/god functions). And the ubiquitous halo, a sun motif used for gods and goddesses thousands of years before the Christian era, repurposed for use above the heads of saints.

So, in like manner, should it be any surprise for actual celebrations of holidays like Christmas to be any different?

But what about it? Can we trace the path of such pre-Christian “Christmas” practices? Just how innocuous, or pagan, are they? And do they connect with these above-mentioned writings of the Hebrew prophets?

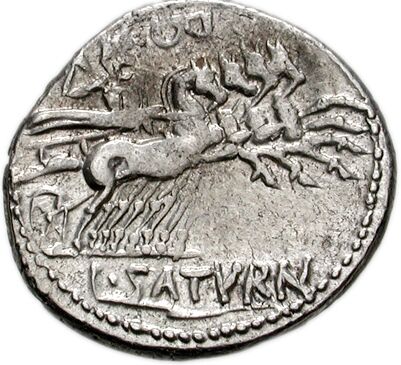

A Merry Saturnalia

Not only can Christmas customs be described as “a descent from seasonal, pagan” practices, they relate specifically to the most famous of the ancient Roman festivals, tied to the same time of the year.

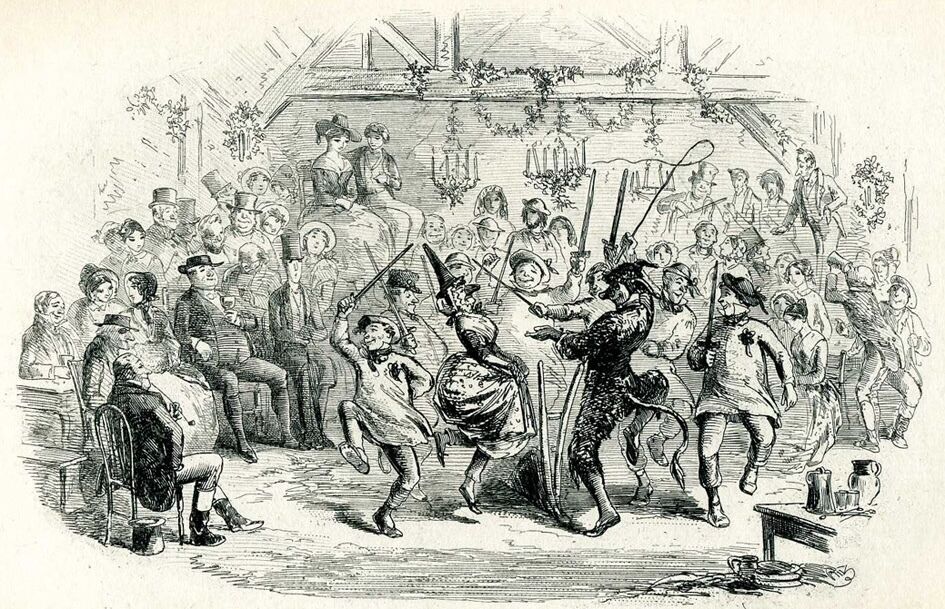

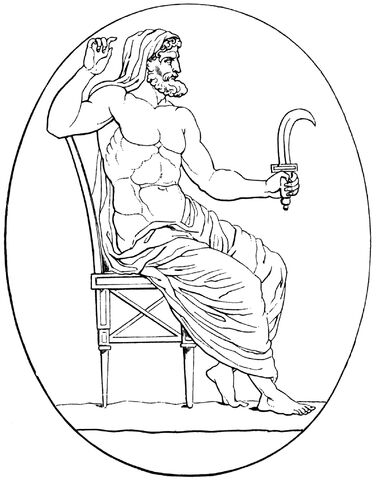

Saturnalia was observed during Roman times (at least as far back as several centuries b.c.e.—the exact origin is unknown). It was a festival of feasting, music, general merry-making, role reversals, hedonism and gladiator combat, in honor of the Roman god Saturn. Gift-giving was one of the most important elements of this festival, and children were bestowed with toys. Saturnalia celebrants would wear a “pileus”—a brimless, conical felt hat. Evergreen wreaths decorated homes, and Roman temples were decorated with evergreen trees. It was a festival of “lights,” with the lighting of candles and various objects. Short messages containing poetry and verse were gifted alongside presents (seen to be an early equivalent to our modern greeting cards). Round decorations, known as “oscilla,” were hung from trees, doors and other objects. (As for the “role reversals” in Saturnalia—men dressing as women, servants as masters, etc—these same practices are a traditional part of Christmas’s “Twelfth Night” celebrations.)

Matt Salusbury summarizes the dates for this holiday in his History Today article “Did the Romans Invent Christmas?”:

Saturnalia grew in duration and moved to progressively later dates under the Roman period. During the reign of the Emperor Augustus (63 bc–ad 14), it was a two-day affair starting on December 17th. By the time Lucian [120–180 c.e.] described the festivities, it was a seven-day event. Changes to the Roman calendar moved the climax of Saturnalia to December 25th, around the time of the date of the winter solstice. … Emperor Caligula (ad 12–41) sought to restrict it to five days, with little success.

Emperor Domitian (ad 51–96) may have changed Saturnalia’s date to December 25th in an attempt to assert his authority. He curbed Saturnalia’s subversive tendencies by marking it with public events under his control. The poet Statius (ad 45–95), in his poem Silvae, describes the lavish banquet and entertainments Domitian presided over ….

Brumalia likewise was a related early festival in honor of Saturn (as well as other select gods), celebrated around the same time of the year. Part of the fertility-centered worship included a small tree, which was supposed to have grown up overnight out of an old dead log (synonymous with the Christmas “Yule log”). Decorations included painted orbs and eggs, as well as holly wreaths and mistletoe. (Pagan superstition held mistletoe to be an aphrodisiac. To this day, “kissing under the mistletoe” is a Christmas tradition. Actually, the plant is toxic.)

Fast-forwarding in time, during the third century c.e., the Roman Emperor Aurelian declared the worship of the sun god Sol Invictus as an official Roman religion, alongside the other traditional Roman deities. December 25 likewise became the official day of worship for this god, essentially merging with Saturnalia/Brumalia and becoming known as the “birthday of the unconquerable sun god.”

The connections to Christmas are obvious. Based on such associations, Christmas celebrations were actually banned in parts of 17th-century Britain and America—the celebrations seen as a heathen custom that “threatened core Christian beliefs” (M. Patiño, “The Puritan Ban on Christmas”). “Most Americans today are unaware that Christmas was banned in Boston from 1659 to 1681,” wrote Joe Kovacs. “Shocking as it sounds, followers of Jesus Christ in both America and England helped pass laws making it illegal to observe Christmas, believing it was an insult to God to honor a day associated with ancient paganism” (Shocked by the Bible: The Most Astonishing Facts You’ve Never Been Told).

It wasn’t until the 19th century, during the reign of Queen Victoria, that Christmas trees started to become popular once again in Britain. Victoria’s German husband, Prince Albert, brought the tradition into the halls of Buckingham Palace—and from there it became popularized throughout the nation.

But how did all of these customs become linked to Christianity? After all, they are not found within the New Testament.

‘Never Shall Age Destroy So Holy a Day!’

The general answer to this question is actually quite simple: In the fourth century c.e., Christianity was adopted as the official religion of Rome. Rather than give up the wildly popular customs and festivals such as Saturnalia, they were simply retained and renamed, appropriating the name of Christ to them.

The above-cited Shelley writes in his Christianity Today article: “Christmas has its origins in the fourth century. December 25, which Christians now herald as Jesus’ birthday, was actually the date on which the Romans celebrated the birth of the sun god. After the Roman emperor Constantine converted to Christianity at the Milvian Bridge in 312, he sought to combine the worship of the sun god with worship of Christ.” It is therefore from this same fourth century that we “coincidentally” see our earliest mention of Christmas on December 25th—in Filocalus’s Chronograph of 354. (Intriguingly, however, this text is not our earliest one presenting a birth date for Jesus; some 150 years earlier, in circa 200 c.e., Clement of Alexandria makes mention of certain proposed birth dates within late April or May.)

“Christmas wasn’t originally part of the Christian liturgical year; nor is December 25 mentioned in the Bible,” relays National Geographic’s An Uncommon History of Common Things. “In the fourth century a.d., Pope Julius i chose that date as a church holiday, in large part attempting to give a religious cast to the Saturnalia festivities.”

The sentiments of the first century c.e. poet Statius, regarding Saturnalia celebrations at the time of the then-emperor Domitian, give a window into the unwillingness to relinquish such a festival, and the desire to perpetuate it “forever.” Statius wrote: “Who can sing of the spectacle, the unrestrained mirth, the banqueting, the unbought feast, the lavish streams of wine? Ah! now I faint, and drunken with thy liquor drag myself at last to sleep. For how many years shall this festival abide! Never shall age destroy so holy a day!” (Silvae, I.6.98ff).

From the New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge: “The pagan festival with its riot and merrymaking was so popular that Christians were glad of an excuse to continue its celebration with little change in spirit and in manner.” Not all, however, were so enthused. The encyclopedia continues: “Christian preachers of the West and the Near East protested against the unseemly frivolity with which Christ’s birthday was celebrated, while Christians of Mesopotamia accused their Western brethren of idolatry and sun worship for adopting as Christian this pagan festival.”

On this contention, the Catholic Encyclopedia notes that “Christmas was not among the earliest festivals of the church …. Origen [a third-century c.e. Christian scholar, widely recognized as a “Church Father”] asserts that in the Scriptures sinners alone, not saints, celebrate their birthday” (“Christmas,” 1908 edition).

Another “Church Father” of the same time period—the Carthage-based Tertullian—lamented (in rather biting language) the tendencies that he already witnessed among Christians of the time, to frequent pagan festivities such as Saturnalia. From his circa 200 c.e. work On Idolatry:

[I]f we have no right of communion in matters of this kind with strangers, how far more wicked to celebrate them among brethren! Who can maintain or defend this? … By us … the Saturnalia and New-year’s and Midwinter’s festivals and Matronalia are frequented—presents come and go—New-Year’s gifts—games join their noise—banquets join their din! Oh better fidelity of the nations to their own sect, which claims no solemnity of the Christians for itself! Not the Lord’s day, not Pentecost, even if they had known them, would they have shared with us; for they would fear lest they should seem to be Christians. We are not apprehensive lest we seem to be heathens! (Chapter xiv)

Nevertheless, in the following centuries, the birthday of Christ was eventually adopted wholesale as a religious festival, with the same midwinter trappings described by Tertullian. Bibliotheca Sacra notes, for example, that the “interchange of presents between friends is a like characteristic of Christmas and the Saturnalia, and must have been adopted by Christians from the pagans, as the admonition of Tertullian plainly shows” (“Christmas and the Saturnalia,” Volume 12).

As for the date itself, Encyclopedia Britannica continues: “[M]ost probably the reason [for choosing December 25 as the birthday of Christ] is that early Christians wished the date to coincide with the pagan Roman festival marking the ‘birthday of the unconquered sun.’” Encyclopedia Americana concludes the same. “[Christmas] was, according to many authorities, not celebrated in the first centuries of the Christian church, as the Christian usage in general was to celebrate the death of remarkable persons rather than their birth. … A feast was established in memory of this event in the fourth century …. [T]he Western Church ordered it to be celebrated forever on the day of the old Roman feast of the birth of Sol, as no certain knowledge of the day of Christ’s birth existed” (1944 edition).

A manuscript from the 12th century Syriac bishop Dionysius bar-Salibi asserts as much: “It was a custom of the Pagans to celebrate on the same 25 December the birthday of the Sun, at which they kindled lights in token of festivity. In these solemnities and revelries the Christians also took part. Accordingly when the doctors of the Church perceived that the Christians had a leaning to this festival, they took counsel and resolved that the true Nativity should be solemnized on that day.”

As for the very fourth century in question? A bishop of this period, Epiphanius of Salamis (circa 310–403 c.e.), decried the placement of Jesus’s birthday on December 25th, for its connection to Saturnalia. (Instead, he opined an early January date.) From his work Against Heresies (circa 374 c.e.):

‘Christ was born on the eighth before the Ides of January [January 6], thirteen days after the winter solstice and the increase of the light and the day.’ Greeks, I mean the idolaters, celebrate this day on the eighth before the Kalends of January [December 25], which Romans call Saturnalia, Egyptians Cronia, and Alexandrians, Cicellia. (4.22.4–5)

Christmas, then, tied to Sol Invictus and Saturnalia—pagan Roman festivals, essentially changing the cast of characters. But is it possible to trace such Roman practices—“proto-Christmas,” in a sense—back even further?

Welcome to Carthage

The Roman pantheon of gods (such as Saturn) is derivative of earlier pantheons. In fact, most pantheons are derivatives and can be traced back in time quite easily. The Roman pantheon is made up of and built upon the Greek pantheon, itself derived from other deities. Saturn’s Greek equivalent was the harvest god Kronos, who was celebrated similarly to Saturn in the Greek festival Kronia (alternatively spelled Cronia, as mentioned by Epiphanius. Note also that one of Kronos’s consorts was the goddess Rhea: She too was symbolized by the evergreen silver fir, which was decorated in her worship). And Saturn and Kronos were derivative equivalents of the god of the Carthaginians: Baal Hamon.

Rome’s Saturnalia traditions are, in fact, believed to have come directly from Rome’s associations with Carthage during the Second Punic War (circa 218–201 b.c.e.).

Carthage, on the shores of modern-day Tunisia, was an infamous, wealthy Phoenician city-state outpost that reached its height in the third century b.c.e. It was established as a colony of the famous biblical Phoenician state of Tyre (a state located just north of Israel). Phoenicia appears to have included at least a significant Canaanite population—and Phoenician gods were largely synonymous with Canaanite gods (hence the familiar deity name, “Baal”).

The Carthaginian god Baal Hamon, “king of the gods,” was a weather god and a god of vegetation, agriculture and plant fertility—as with the biblical “Baal,” and as with the equivalent Roman Saturn and Greek Kronos. And what the Carthaginians (as with the biblical Phoenicians) were arguably most famous for was child sacrifice.

The god Baal Hamon—later Kronos/Saturn—had a thirst for human blood. Few realize that seemingly innocuous Christmas customs derived from Saturnalia are actually originally derived from bloody Phoenician Baal worship.

Baal Worship

The Carthaginian practice of child sacrifice before Baal Hamon is especially infamous in the ancient world. Specifics of the rituals are recorded in brutal detail in Greek and Roman writings, and archaeological discoveries of such have been made. Numerous early historians, such as Cleitarchus, Plutarch and Diodorus, describe children—up to at least four years old—offered en masse at Carthage, placed one by one into the outstretched and scalding bronze hands of the god before them. The children would be burned alive in the hands and would slip through the fingers into a cauldron below. (It was said that the lips of the child would quickly shrivel away due to the intense heat, giving the impression that the child was grinning.) The sacrificial area would be filled with the noise of drums and flutes, drowning out the screams. If devotees did not have their own children to offer, they could simply purchase children from the poor of the city. (You can read a collection of such accounts here.)

This Phoenician practice of Baal-worship was described and condemned throughout the Bible. “Enflaming yourselves with idols under every green tree, slaying the children …” (Isaiah 57:5; kjv).

Since Saturn and Kronos were derivatives of Baal Hamon, they were respected in their various regions with derivative customs. Both were seen as cruel gods requiring human blood. According to Greek mythology, Kronos was prophesied to be overthrown by one of his sons—and thus ate them up as soon as they were born. The derivative Roman story of Saturn is the same.

By the time of the “civilized” Roman Republic, citizens of Italy began to look on such sacrifices with a horrified awe. Instead of offering children, they deemed it acceptable to switch to the more “enlightened” sacrificial practice of offering gifts to one another at Saturnalia.

Still, Saturn was satiated with at least some bloodshed—the highly anticipated gladiator and gladiatrix (female gladiator) combat on Saturnalia was seen as supplying the necessary human offerings.

Among the many gifts given on Saturnalia were numerous ancient pottery and wax figurines. The fifth-century c.e. Roman writer Macrobius explained that these served as replacements for genuine sacrifices. As for the oscilla, the Saturnalia “baubles” hung from trees and other objects? For the Romans, such decorations served to replace hanging “heads” of sacrificial victims. (See, for example, entry “Oscilla” in A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, 1890.)

Still, Carthaginian worship primarily occurred later than our biblical references. Can we trace the Carthaginian worship back further into biblical times?

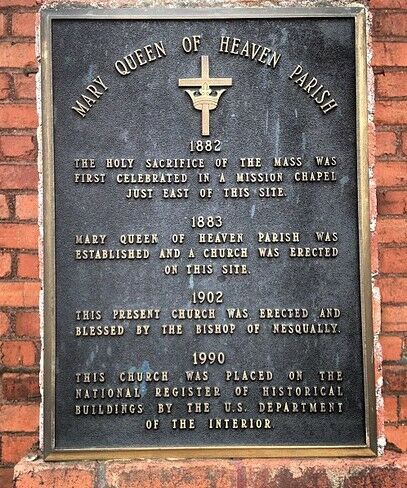

Queen of Heaven

There were two primary deities in Carthage: Baal Hamon and his consort, the goddess Tanit. Tanit was known as the “Queen of Heaven.” (Curiously, also beginning around the fourth century c.e., the same title “Queen of Heaven” began to be applied to Jesus’s mother Mary.)

Since Carthage was a Phoenician outpost, the gods of Carthage are easily traced back to the Phoenician homeland on the north of Israel. Tanit is widely known and easily identified as the Carthaginian name for the Phoenician goddess Astarte.

This goddess is named in several biblical passages as “Ashtoreth.” The Prophet Jeremiah describes her worship: Just before our above-cited Jeremiah 10 tree passage, the prophet condemns the Israelites for Phoenician-style child sacrifice, including worship of “the queen of heaven” (Jeremiah 7:18; compare also chapter 44). Astarte was the chief goddess of the Phoenicians and Canaanites, and Solomon was condemned for bringing her worship into Israel through his many wives (1 Kings 11).

We now start to unravel a real spider’s web of parallel deities. Astarte is known, perhaps even more famously, by her earlier Babylonian name Ishtar—the Phoenician-Canaanite pantheon itself being derived from the Mesopotamian pantheon. Truly, this goddess was renowned in various forms all over the ancient world. Astarte/Ishtar was consort to the god Baal and the god Tammuz (also mentioned in the Bible—see Ezekiel 8). And the union of these gods goes back even further, ultimately deriving in origin from the Sumerian deities Inanna (Ishtar) and Dumuzi (Tammuz). In Sumerian inscriptions, Inanna refers to herself as the “Queen of Heaven,” and Dumuzi is the god of agriculture. This period (the third millennium b.c.e.) is about as far back as we can go based on inscriptions, given Sumer is considered man’s earliest civilization (fitting with the biblical “Shinar” civilization led by Nimrod; see Genesis 11:1–2).

But what does any of this have to do with trees?

Trees Galore

To the Sumerians, Dumuzi was represented by the evergreen date palm—a tree common to that region. Dumuzi was also generalized as a god of vegetation, representing the power that caused trees and crops to grow. According to the early Sumerian and Akkadian myths, Dumuzi was slain, leaving the goddess Inanna widowed. Dumuzi spent part of every year tormented in the Underworld. Inanna’s resulting yearly grief caused the winter season, before his eventual rebirth.

One particular Sumerian story applying to this theme is “Inanna and the Huluppu Tree.” This Sumerian tale describes a “tree” for which violence “plucked up its roots and tore away its crown.” The uprooted tree was brought to Inanna, who “tended” it, prophesying that it would become a “fruitful throne” and a “bed” for her. Inanna wept over the tree, and vengeance was executed on those who did violence to it.

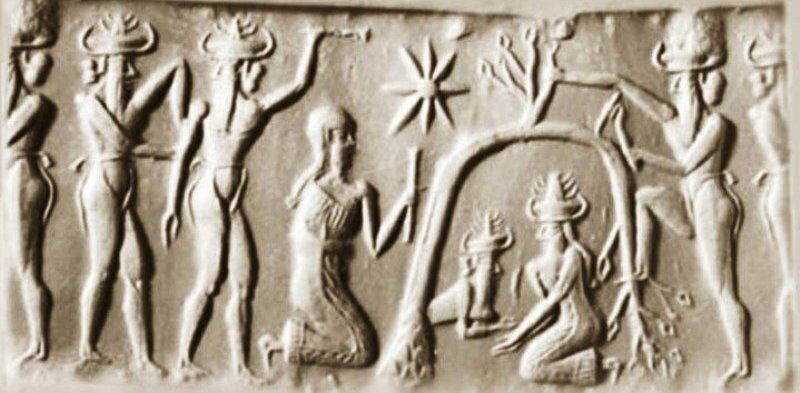

The Huluppu tree story is associated in the myth with the underworld. The symbolic connection of the tree with Inanna’s fallen “tree”-lover, Dumuzi, is evident. The below image is an impression from a Sumerian cylinder seal, depicting the tree, topped with Inanna’s star, and a deified “king” emerging from underneath, to the right of the kneeling Inanna. The revived tree and throne apparently represented a reborn Dumuzi following his season in the underworld, and the rebirth of plant life.

As with the celebration of “rebirth,” Inanna’s weeping for the death of Dumuzi was replicated through the ages by womenfolk of different regions and respective religions. Ezekiel 8:14 describes Israelite women some 2,000 years later, “weeping for Tammuz.” The Dumuzi-Inanna-tree custom likewise spread from Sumer through the Levant, Egypt, Greece and Rome, in varying forms of mother-son/consort worship.

The union was carried on in Egypt in the form of the Isis-Osiris story—Isis representing Inanna, Osiris her slain lover, and Isis’s child, Horus, the reborn Tammuz. Osiris represented tree rebirth. Following the slaying of Osiris by the god Set, Isis set about looking for his remains, which she found in an evergreen tree. (According to a later retelling by the first-century Greek philosopher Plutarch, this tree was cut down and brought into the palace of a Phoenician king.) Isis cast a spell on Osiris’s mutilated male member she had found and was impregnated—thus from a tree, the god Osiris was reborn as Horus.

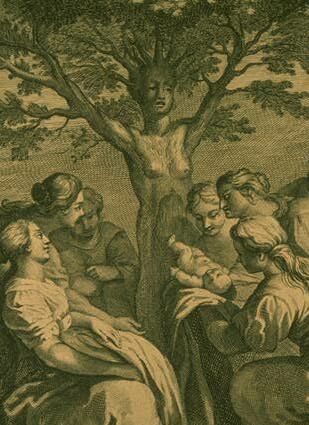

The story continues through into Greek mythology, via Phoenicia. In Greece, Tammuz was equivalent to the god Adonis. Adonis was god of fertility and vegetation, born of the goddess Myrrha, who in this story had been transformed into an evergreen myrrh tree—below her branches, she gave birth to Adonis. (Adonis is also considered to be a manifestation of the god Baal.)

And while the Phoenician Baal had his own separate worship practices that extended into the Greek Kronia and Roman Saturnalia, his “reborn” Greek avatar Adonis likewise had his own observance, Adonia: a sacred day in which the “women wept” for his death.

The Phrygians, Greeks and Romans continued the myth with yet another set of parallel deities: Attis and his mother-consort, Cybele. Attis was a god of vegetation and sun god, who died and was transformed into a pine tree, associated with all the related “weeping.” His death and rebirth were a representation of the winter period, and the death and rebirth of plant life. (In 2007, a wooden throne was discovered in the Roman city Herculaneum, with a depiction of the god Attis sitting beneath a pine tree.) Also associated with the god Attis was the “Phrygian cap,” a tall, soft conical hat similar to the Roman pileus hat worn during Saturnalia. His mother-consort Cybele was worshiped by cutting down a pine tree and setting it up in her temple, decorating the branches and hanging wreaths.

One final (and somewhat gory) note: Attis was a god associated with emasculation. Coincidentally(?), he shared this emasculation/castration connection with the more widely worshiped Greco-Roman god Kronos/Saturn, as well as the Egyptian Osiris (recall that it was this body part that Isis found in a tree, from which she impregnated herself). But perhaps this connection is not so coincidental: All the way back to the ancient Sumerian literature, the tree was symbolic of the “male member”—and the names for both were pronounced the same way (“gish”). Thus, befitting the traditions of a “tree cut down” and a seed of “rebirth” ….

And on it goes. From roots in the “first civilization” in Sumer and Babylon, the family tree of gods continued to grow. Some interchangeable, some derivative, some myths built upon, some gods split into separate deities yet with related worship, some blended together—but all sharing a common core. With the Roman adoption of Christianity, then, the “birth” traditions of the respective deities were fitted to the birth of Jesus; the death and “weeping,” fitted to the crucifixion. Plus all of the related general observances, specific to gods to which Jesus was later equated.

Winter ‘Dismay’

Back to our passage in Jeremiah. At the start of this article, a critical part was left out (italicized below):

Hear ye the word which the Lord speaketh unto you, O house of Israel: Thus saith the Lord, Learn not the way of the heathen, and be not dismayed at the signs of heaven; for the heathen are dismayed at them. For the customs of the people are vain: for one cutteth a tree out of the forest, the work of the hands of the workman, with the axe. They deck it with silver and with gold; they fasten it with nails and with hammers, that it move not. They are upright as the palm tree, but speak not … (Jeremiah 10:1–5; kjv).

Here we see that this tree practice was done in relation to the signs of heaven and “dismay.” This fits exactly with the religious practices through time—thousands of years before Jeremiah and thousands of years after—surrounding the winter period. The “dismay” at the death of the god of agriculture—the death of vegetation, plant life, the shortening hours of daylight from the sun—and all the related symbolism and superstition wrapped up in the cut down evergreen.

It is no coincidence, then, that December 25 on the original Julian calendar was the date of the winter solstice, the dead of winter—this marking the time from which the days begin to lengthen once again, thus befitting sun- and agriculture-based worship. (Our modern Gregorian calendar is slightly different, with the winter solstice occurring on December 21.)

And again, there is no mention of this date anywhere in the New Testament. In fact, based on the New Testament account, Jesus would not have been born anywhere near this date. Probably the point most often given for this is that the shepherds were still out in the fields all night with their flocks (Luke 2:8). On this, the 19th century French theologian Edmond Stapfer commented in his book Palestine in the Time of Christ: “The sheep passed the whole summer in the fields. … In the month Marchesvan, which corresponds to the half of October and the half of November, the sheep were brought back into the fold and kept there through the winter. This fact shows that there must be some error in the traditional date of the birth of Jesus. In December the shepherds were not in the fields by night.”

Adam Clarke’s Commentary concurs, albeit opining an even earlier timeframe for the corralling of sheep: “As these shepherds had not yet brought home their flocks, it is a presumptive argument that October had not yet commenced, and that consequently, our Lord was not born on the 25th of December, when no flocks were out in the fields; nor could He have been born later than September, as the flocks were still in the fields by night. On this very ground, the nativity in December should be given up. The feeding of the flocks by night in the fields is a chronological fact.”

There are additional points besides, including that the taxation of the Jews (Luke 2:4) would not have taken place at this time of year and that the date does not fit with the starting time frame for the Abiah priestly rotation in the temple (Luke 1:5–9; 1 Chronicles 24)—to name a few examples.

In a recent BBC documentary, “The Astonishing Pagan Origins of Christmas,” the interviewer asked University of Bristol Prof. Ronald Hutton: “What happens to the pagan midwinter festival when Christianity comes along?” Hutton: “Quite simply, Christianity takes it over gloriously and makes it Christmas.

If you read the Gospels, there’s nothing in them to say exactly at what time of the year Christ was born. Although, if it’s when the shepherds watch their flocks by night, it’s most likely to be May or September. By the fourth century, when Christianity is becoming dominant, Christmas settles at midwinter, with this symbolism of the rebirth of the sun, becoming that of the rebirth of the Son.

Indeed, a September birth date would fit well with a standard internal biblical calculation of Jesus’s ministry lasting about 3.5 years, from the age of 30 until his crucifixion on Passover, in the Spring.

Still, there is no command or even suggestion anywhere in the New Testament to celebrate Jesus’s birth. (What is repeatedly commanded is the commemoration of his death on Passover.) To quote again from the Catholic Encyclopedia: “Christmas was not among the earliest festivals of the church …. [The early Christian scholar Origen] asserts that in the Scriptures sinners alone, not saints, celebrate their birthday.”

Similarly, in the context of describing various Jewish laws, the first-century Jewish historian Josephus wrote that “the law does not permit us to make festivals at the birth of our children” (Against Apion, 2.26). This statement, and that of Origen, is connected to each and every biblical mention of birthday celebrations as being in a sinful context—as well as, in every case, a related tragedy occurring. (There is the pharaoh’s birthday and the hanging of his baker—Genesis 40; the celebrations of Job’s children, “each one upon his day,” for which Job offered sacrifices for forgiveness, until tragedy struck on such an occasion—Job 1:4–5, 18–19, compare with the language of 3:1–3; in the New Testament, the beheading of John the Baptist on Herod’s birthday—Matthew 14.) Of this, Origen writes further still (from his Commentary on Matthew): “[T]he worthless man who loves things connected with birth keeps birthday festivals; and we, taking this suggestion from him, find in no Scripture that a birthday was kept by a righteous man.”

Ironic, then, that the single most widely celebrated religious festival on Earth is a holiday that is at best entirely unmentioned in the Bible—and at worst, a day that “sinners alone, not saints, celebrate.”

‘Beware Babylon’

The pagan, pre-Christian roots of Christmas are clear—and even widely recognized today, among religious leaders, in religious education and in pop culture. So it should be no surprise to find similar Christmas-tree related practices, in worship of related pagan deities, being decried in the Hebrew Bible centuries before Christianity. Even in the New Testament, as early as the late first century c.e., the Apostle John highlighted as much, in his prophetic vision of a “mystery religion” counterfeiting Christianity, with practices stemming from ancient Babylon:

I saw a woman [symbol of a church] sit upon a scarlet coloured beast [symbol of a nation/empire] …. And upon her forehead was a name written, Mystery, Babylon the Great, the Mother of Harlots and Abominations of the Earth … Come out of her, my people, that ye be not partakers of her sins, and that ye receive not of her plagues. … [F]or she saith in her heart, I sit a queen …. [F]or by thy sorceries were all nations deceived. (Revelation 17:3, 5; 18:4, 7, 23)

John’s statement in Revelation is much the same as the one written some 700 years earlier by Jeremiah. (The chapter, in part, answers to such claims that pagan practices can be selectively “baptized” into Christian practice.) From the New English Translation: “The Lord says, “Do not start following pagan religious practices. Do not be in awe of signs that occur in the sky even though the nations hold them in awe. For the religion of these people is worthless. … And they do not have any power to help you. … These gods did not make heaven and earth. They will disappear from the earth and from under the heavens. … The Lord, who is the inheritance of Jacob’s descendants, is not like them. He is the one who created everything” (Jeremiah 10:2–3, 5, 11, 16).

Continuing the parallel passage in Isaiah: “To whom then will ye liken God? or what likeness will ye compare unto him? The workman melteth a graven image, and the goldsmith spreadeth it over with gold, and casteth silver chains. He that is so impoverished that he hath no oblation chooseth a tree that will not rot; he seeketh unto him a cunning workman to prepare a graven image, that shall not be moved. Have ye not known? Have ye not heard? hath it not been told you from the beginning? have ye not understood from the foundations of the earth?” (Isaiah 40:20–21, kjv).

The passage continues to pose the same question: Should God be likened, or equated, or compared, with such? To Saturn? To Sol Invictus, the sun god—from whose “birthday” at winter solstice the days begin to elongate once again? To vegetation and agriculture? To the coming and going of the seasons themselves? Verses 25–28: “To whom then will ye liken me, or shall I be equal? saith the Holy One. Lift up your eyes on high, and behold who hath created these things … the everlasting God, the Lord, the Creator of the ends of the earth.”

Article updated 03/12/24. For more in this series: