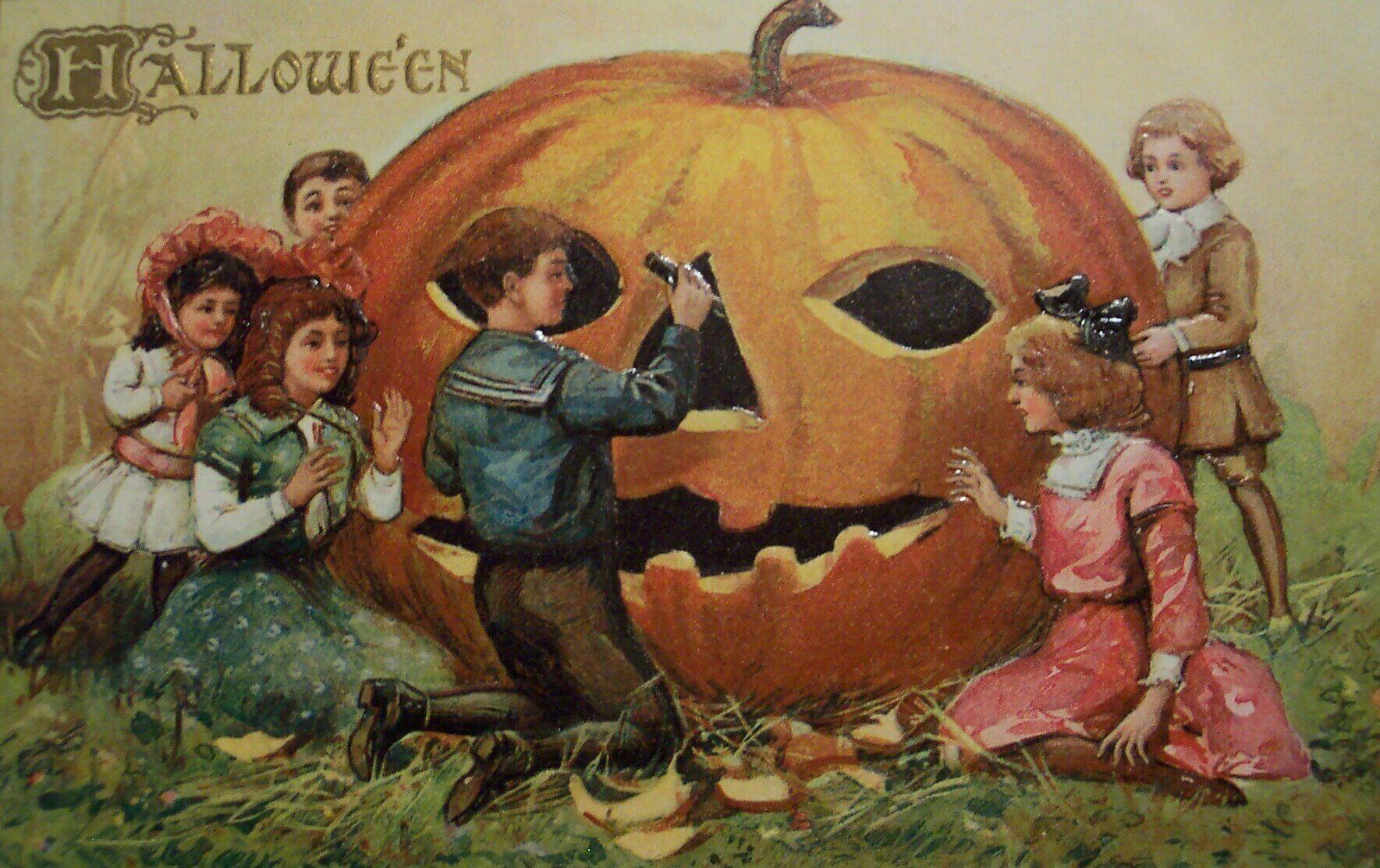

Carved pumpkins. Ghoulish costumes. Trick-or-treating. Bonfires. Pranks and horror films. It’s one of the most peculiar festivals in the Western world—and at that, named among the yearly “Christian” festivals.

Yet neither Halloween nor its peculiar practices are mentioned anywhere in the New Testament. There is, however, a striking account in the Old Testament—the Hebrew Bible.

Where—and who—did this peculiar festival come from?

Opening Up the Otherworld

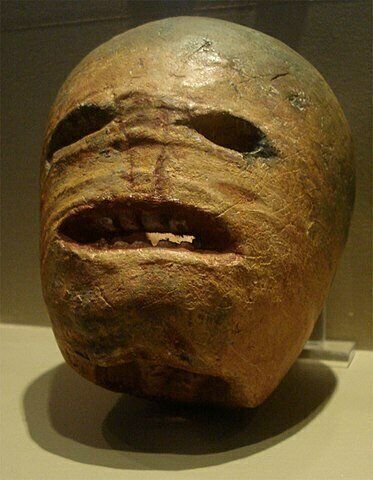

Halloween, celebrated on the evening of October 31, is usually traced back to the pagan Celtic Druids and their festival of Samhain, which took place on November 1 (yet started the evening before, October 31—the Druids calculated days from sunset to sunset). Samhain was known as the Feast of the Dead, with the belief that on this date the dead could return to the land of the living. Burial mounds in Celtic Ireland, Scotland, Wales and other regions were opened and bonfires were lit so that the dead could make their way home. Extra places were set at tables, and food laid out, for those who had died that year.

This festival thus marked what was believed to be a liminal time of the year, in which the boundaries between our world and the Otherworld thinned, also allowing evil spirits to emerge and possess the bodies of the living. In order to prevent this from happening, the Celts dressed in grotesque costumes, leaving treats outside their homes to pay off these evil spirits.

Historian Martyn Whittock summarized this “festival of the dead on 31 October” in his book Celtic Myths & Legends as follows: “[T]he feast of Samhain, festival of the dead, which was also a harvest festival … was considered a time of year when the veil between this world and the spirit world was thin and communication and movement between the two might occur. … In early medieval Ireland it was believed that at the festival of Samhain the earth-bound spirits were temporarily free to leave the sídhe [“fairy mounds”—the ancient burial mounds dotted around the Irish landscape] since it was believed that at this time the boundary between the natural would and the Otherworld no longer operated.”

Samhain was the most important of the Celtic holidays and is mentioned in the earliest Irish literature. During the medieval period, its celebration became fixed to October 31–November 1. However, in earlier periods, it was not a fixed date applied to the Roman calendar; the festival marked the end of the harvest season and the beginning of winter, halfway between the equinox and solstice, thus falling typically within early November.

Encyclopedia Americana summarizes Halloween as “clearly a relic of pagan times.” The famous 20th-century anthropologist Ralph Linton wrote that the “earliest Halloween celebrations were held by Druids in honor of Samhain, Lord of the Dead, whose festival fell on November 1” (Halloween Through Twenty Centuries). Encyclopedia Britannica states the following about Halloween (including peculiar associated customs, such as apple bobbing):

Hallowe’en, or All Hallow’s Eve, the name given to the 31st of October as the vigil of Hallowmas or All Saints’ Day. Though now known as little else but the eve of the Christian festival, Hallowe’en and its formerly attendant ceremonies long antedate Christianity. The two chief characteristics of ancient Hallowe’en were the lighting of bonfires and the belief that of all nights in the year this is the one during which ghosts and witches are most likely to wander abroad. … [I]t was a Druidic believe that on the eve of this festival Saman, lord of death, called together the wicked souls that within the past twelve months had been condemned …

[I]t is clear that the main celebrations of Hallowe’en were purely Druicial, and this is further proved by the fact that in parts of Ireland the 31st of October was, and even still is, known as Oidhche Shamhna, “Vigil of Saman.” On the Druidic ceremonies were grafted some of the characteristics of the Roman festival in honour of [the goddess] Pomona held about the 1st of November, in which nuts and apples, as representing the winter store of fruits, played an important part. Thus the roasting of nuts and the sport known as “apple-ducking”—attempting to seize with the teeth an apple floating in a tub of water—were once the universal occupation of the young folk in medieval England on the 31st of October. (11th edition, article “Hallowe’en”)

‘Christian’ Adoption

By the ninth century c.e., Roman Christianity had spread into Celtic lands, and it is from this point forward—beginning first in these British Isles—that a festival appears on November 1, known variously as All Soul’s Day, Hallowmas, or All Hallow’s Day, with the evening prior (October 31) observed as All Hollow’s Eve. (It is from this name that we get the modern Halloween/Hallowe’en, “Hallow’s Evening”). By the 10th century, this festival was extended from just the British Isles to apply to the wider Catholic Church. According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, November 1 is the day “to honor all the saints, known and unknown” who have since died (article, “All Saints’ Day”).

Linton describes the grafting of this Celtic festival of the dead into Catholicism as a practice “quite in line with church policy of incorporating harmless pagan folk ideas” (op cit)—adopting the practices of pagan cultures as a means of drawing in converts. “A famous proponent of this practice was Pope Gregory the Great,” wrote Prof. Andrew McGowan, “who, in a letter written in 601 c.e. to a Christian missionary in Britain, recommended that local pagan temples not be destroyed but be converted into churches, and that pagan festivals be celebrated as feasts of Christian martyrs” (article, “How December 25 Became Christmas”).

In the rather flamboyant words of Dorothy Wood in the Wichita Beacon (actually condemning “Christianity” for plagiarizing pagan festivals): “This ancient night of revelry for the devil and his cohorts has degenerated. … It’s the Christians who are to blame. For centuries, they’ve been grabbing off all the old heathen festivals. The midwinter feast with its greens and feasting and drinking has become Christmas. The wild spring festival has become Easter, and the worshipers of Christ boldly use the old pagan symbols of fertility—chicks and rabbits and eggs. Now they’ve completely taken over Halloween” (October 30, 1959; emphasis added).

Halloween, of course, is nowhere mentioned in the New Testament as a Christian festival. If anything, the commemoration of a festival built around worship of the “Lord of Death” is ironic—to quote the words of Jesus: “God is not the God of the dead, but of the living” (Matthew 22:32; also Mark 12:27; Luke 20:38). The important question thus follows: Which deity is being worshiped on Halloween? And, can we trace the earlier origins of this festival?

There is a fascinating possible parallel—one described in the Old Testament, the Hebrew Bible.

The ‘Sins of Jeroboam’

This connection was highlighted especially by the late Dr. Herman Hoeh and Gerhard Marx. It pertains to a particular event in the religious formation of the northern Kingdom of Israel, and the numerous parallels highlighted between the druid class and priests of the “religion of Jeroboam.”

First, we must briefly mention one of the important holy day festivals that is commanded in the Bible—the Fall harvest festival, Sukkot (the “Feast of Tabernacles”). This seven-day festival, described in Leviticus 23 (and elsewhere), begins on the 15th day of the seventh month on the Hebrew calendar—generally falling around the end of September or start of October on the Gregorian calendar. (It’s also of note that this festival was kept in the New Testament by Jesus, his disciples, and the early church—i.e. John 7; 12:12-20, Acts 18:21.) The Feast of Tabernacles/Sukkot is one of the lynchpin and ultimate festivals in the holy day calendar, described in numerous passages in the Hebrew Bible and New Testament. (Zechariah 14:16-19 even prophesies that “all the nations that go not up to keep the feast of tabernacles” in the future—including Gentile nations—will be cursed.)

Enter King Jeroboam i.

In the late 10th century b.c.e., following the reign of King Solomon, a dramatic split took place in Israel’s united monarchy, due to the sins of Solomon. Ten tribes split away from the Jerusalem-based throne of David. Led by King Jeroboam, they established the northern kingdom of Israel (from this point forward, separately referred to generally as Israelites). Two tribes (and another half tribe) remained to make up what became the southern kingdom of Judah (from this point forward, generally referred to collectively as Jews. 2 Kings 16:5-6, for example, describes war between “Israel” and “the Jews”!).

1 Kings 11 relates that God gave Jeroboam a chance to establish himself as a righteous king over a prosperous kingdom. However, Jeroboam began to fear that Israelites traveling to the temple in Jerusalem to worship would begin to turn away from him and his rule—so he concocted a plan. The last half of 1 Kings 12 describes a new religion established by Jeroboam, with more “convenient” worship centers in Dan (in the north) and Bethel (in the south), centered around cattle worship (verses 28-30). Jeroboam appointed as his priests not the Levites, but the “lowest of the people” (verse 31; King James Version).

The last part of the chapter describes the central feast of his newly established religion.

“And Jeroboam ordained a feast in the eighth month, on the fifteenth day of the month, like unto the feast that is in Judah, and he offered upon the altar. So did he in Bethel, sacrificing unto the calves that he had made …. So he offered upon the altar which he had made in Bethel the fifteenth day of the eighth month, even in the month which he had devised of his own heart; and ordained a feast unto the children of Israel …” (verses 32-33; kjv).

These verses describe Jeroboam establishing a counterfeit feast exactly one month after Sukkot. This feast therefore relates to the end of October/early November on the Gregorian calendar—exactly the same time frame as the original Celtic Samhain (before it was eventually fixed on the Roman calendar to the evening of October 31. The Israelites likewise calculated their days and festivals from sunset to sunset—i.e., Leviticus 23:32.)

Coincidence? Both Samhain and Jeroboam’s feast occurred at the same time of the year. Both were harvest-related festivals. Both were originally seven days long (the wider Samhain festival being a seven-day event, centered around the primary day of worship). Both were the chiefest festivals of their respective religions. Both were reckoned from evening to evening. Both were central to a cattle cult (the Celts were a transhumance-based society, and Samhain marked the time when the cattle were brought down from summer pastures, at which time select cattle were sacrificed upon Samhain bonfires). Both included related burning and sacrifices.

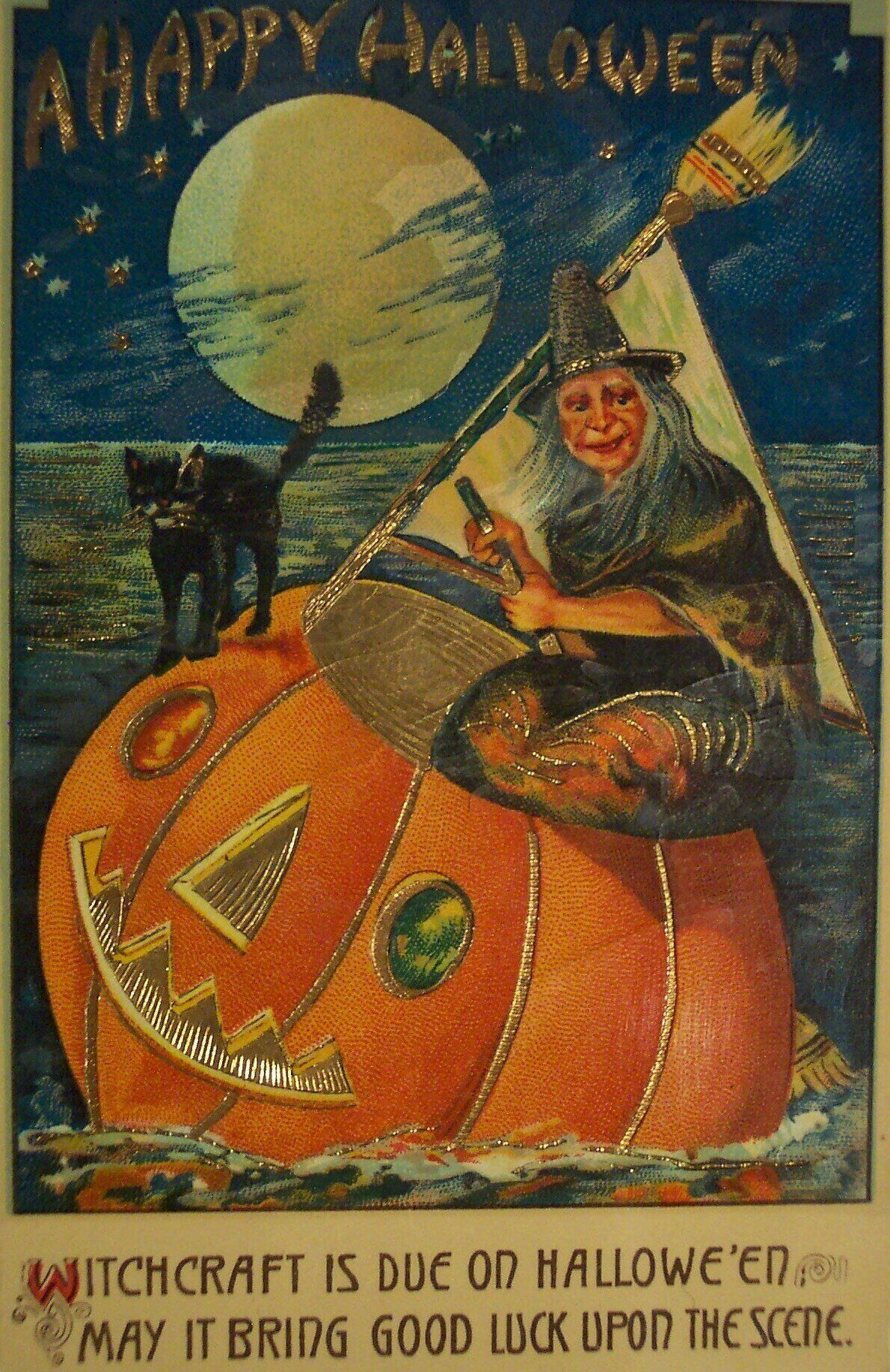

And both Samhain and Jeroboam’s feast had magic and witchcraft as a central religious element. From this point forward, the religion and customs of the northern kingdom of Israel became known as the “sins of Jeroboam”—featuring witches and wizards using “divination and enchantments” (2 Kings 17:16-17).

There is even a potential biblical connection between this festival and the reemerging of the dead.

As Jeroboam was worshiping at his altar in Bethel (apparently during this new festival, in the eighth month), a prophet of God arrived, warning the king that for these sins a future leader named Josiah would come on the scene and open the graves of Jeroboam’s pagan priests, exhuming the bodies and burning them to ashes on the altar (1 Kings 13:2). This prophecy led to a general fear among Jeroboam’s priests (one of which hatched a crafty plan to try to preserve his remains in-state; verses 31-32). Three hundred years later, the prophecy was fulfilled, and a king named Josiah was coronated. He summarily exhumed and burned the bones of the dead priests (2 Kings 23:15-16). It is therefore interesting that great lengths are taken in the Halloween–Samhain festivals to appease the emerging dead from their graves at this time of year.

All of this is simply the tip of the iceberg in the deep connections between the early Israelite pagan priests, and the later-emerging class of Celtic Druids in Europe (an emergence actually following the deportation and disappearance of the “lost 10 tribes”—2 Kings 17—who were banished for their disobedience). Parallels in customs are rife, from festivals to clothing to symbols to ritual sites—even a language and migratory link and a specific connection to the tribe of Dan (within which was Jeroboam’s northern center of worship). For more information on this subject, take a look at Brad Macdonald’s article “Were the Celtic Druids Pagan Israelite Priests?”

In his 1959 article “Halloween: Where Did It Come From?” Dr. Herman Hoeh summarized:

At the time the tribes of Israel split into two nations, King Jeroboam adopted in place of the biblical Feast of Tabernacles (ordained by God to be kept forever in the seventh month) a pagan celebration to be observed in the middle of “the eighth month.” The year used to begin in the spring of the year and the eighth month extended from the middle of October to the middle of November. And the middle of the month corresponded to the very time of Halloween today! In fact, “October” means the eighth month in Latin. Since the days of Jeroboam, the 10 tribes of Israel—who later migrated into northwest Europe—have continued to celebrate this pagan harvest festival, which today is called “Hallowe’en”!

What’s the Big Deal?

But back to the original, theological question—and its natural extension: If Halloween is, at its core, a day centered around the “Lord of Death,” and the God of the Bible is repeatedly called the God of the living (also note Psalm 6:6; 115:17)—who exactly is being worshiped on this festival? And does it matter?

The New Testament itself describes “him who has the power of death, that is, the devil” (Hebrews 2:14; Revised Standard Version). And the founder of the Church of Satan, Anton LaVey, himself famously stated outright (in contrast to the above-cited Witchita Beacon’s Dorothy Wood): “I am glad that Christian parents let their children worship the devil at least one night out of the year. Welcome to Halloween.”

Numerous scriptures throughout the Bible expressly forbid various Halloween practices and traditions. As Dennis Leap summarized:

All Hollow’s Eve is still a festival of the dead. Even though Christian leaders have attempted to put a holy face on the day by having people pray for the dead, the custom does not make the evening Christian. …

Some of the most popular costumes for adolescents and teens are werewolves, vampires and zombies. What are people thinking? Even home decorations feature satanic themes of darkness, death and misery. The colors black, orange and red—regarded as essential for Halloween home decorating—are considered Satan’s colors. Spiders and spider webs are featured in Halloween decorating. Did you know that the spider is considered one of Satan’s followers? Witches are given place of honor in many homes during Halloween. Yet the Bible says, “Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live” (Exodus 22:18; kjv). … Halloween is one of the most overtly pagan festivals” (article, “Unmasking the Origins of Halloween”).

Isaiah 8:19 reads, “When someone tells you to consult mediums and spiritists, who whisper and mutter, should not a people inquire of their God? Why consult the dead on behalf of the living?” (New International Version). Deuteronomy 18 warns: “There shall not be found among you … one that useth divination, a soothsayer, or an enchanter, or a sorcerer [witch], or a charmer, or one that consulteth a ghost or a familiar spirit, or a necromancer [one who calls up the dead]. For whosoever doeth these things is an abomination unto the Lord; and because of these abominations the Lord thy God is driving them [the Canaanites] out …” (verses 10-12).

And by the same token, it was for the very festival and “sin of Jeroboam” that the entire northern kingdom of Israel was utterly conquered and driven out—“vanishing” from world view at the end of the eighth century b.c.e. As 2 Kings 17:16-18 relate: “And they forsook all the commandments of the Lord their God, and made them molten images, even two calves … they caused their sons and their daughters to pass through the fire, and used divination and enchantments, and gave themselves over to do that which was evil in the sight of the Lord, to provoke Him to anger; that the Lord was very angry with Israel, and removed them out of His sight: there was none left but the tribe of Judah only.”

The Prophet Jeremiah relays divine condemnation for the practice of “borrowing” pagan traditions. “Learn not the way of the heathen …” (Jeremiah 10:2; kjv). Deuteronomy 12 similarly warns, “Take heed to thyself that thou be not ensared to follow them [the conquered heathen nations], after that they are destroyed from before thee; and that thou inquire not after their gods, saying: ‘How used these nations to serve their gods? even so will I do likewise.’ Thou shalt not do so unto the Lord thy God …” (verses 30-31).

Halloween is clearly a festival in which horror and violence—pretend or real—is indulged. Yet the Bible says that “the wicked and him that loveth violence His soul hateth” (Psalm 11:5. Another thing: Is it just coincidence or accident that Halloween is often accompanied by various incidents of literal bloodshed, gore and tragedy?). Another prevalent belief is that dressing up in satanic costumes is in mockery of Satan. “Fools make a mock at sin,” says Proverbs 14:9 (kjv. The New Testament book of Jude even notes that the powerful archangel Michael dared not taunt Satan—verse 9).

Halloween is a festival of horror and darkness. Yet the Bible repeatedly describes God as a God of light and living. “Woe unto them that call evil good, And good evil; That change darkness into light, And light into darkness …” (Isaiah 5:20). “[T]he path of the just is as the shining light, that shineth more and more … [t]he way of the wicked is as darkness” (Proverbs 4:18-19; kjv). And the last verse of Psalm 56: “Thou hast delivered my soul from death … that I may walk before God in the light of the living.”

God is light, and His holy days reflect that light. Halloween, on the other hand—as shown by the fruits—is the very antithesis, a festival ultimately in worship of a being who is the antithesis of God.

Article updated 07/03/24. For more in this series: