If everybody’s doing it, that makes it OK. Well, no. But that does make it a cultural universal—the anthropological name for something done, in some form or other, by every human culture around the world. This includes religion, music, art, marriage, war, families, gender roles, laws, taboos, personal names, etiquette, morals, etc. The cultural universal can be somewhat of a pain for evolutionists to try to explain. In a world where societies are supposed to have migrated and evolved and changed and developed and faced various extinctions so separately, how could it be that every culture does these things?

One of the primary (and very obvious) cultural universals is language. In some form or other, it is, of course, found worldwide across all cultures. And not just language in general, but many basic elements of language are also cultural universals, used by all humans (we’ll get into those specifics further down). Language is one of our greatest human attributes, and one we almost exclusively take for granted. “Animal language” is a closed system, which consists of a very small, finite number of simple, expressible “ideas.” Human language is an open system, virtually infinite in what can be expressed. No creature can produce the range of sounds a human can, and the precise makeup and combined use of human tongue, larynx and related oral and nasal passageways all enable the unique ability of human speech.

Have you ever wondered where this human language came from? How did we begin talking and writing? How do the anthropologists explain it, according to the theory of evolution, and what does the Bible say? Does archaeology give us any leads as to the earliest development of language?

This is the second in a series of articles on cultural universals—examining and comparing the secular and biblical accounts of our most human characteristics.

The Commonality of Language

As stated above, not only is language in general a cultural universal, but also several aspects of language. Things like synonyms and antonyms, metaphors, abstract concepts, “bad” words, classifications of various things, personal names, time—even the fact that language is always translatable. Scientists have tried to create a computer-generated, “untranslatable” language—when tested on humans, even this failed.

Based on his close study of 30 different languages, American linguist Joseph Greenberg (d. 2001) derived a list of at least 45 separate linguistic “universals” common to man.

Recent scientific studies have helped to show that language is actually hardwired into the human brain. The scanned brains of various individuals showed the same sensitivity to “language universals.” Results show that “sound patterns of human language reflect shared linguistic constraints that are hardwired in the human brain already at birth.” Multiple studies have been carried out, including showing subjects certain words completely foreign or made up, and asking what imagery they invoke. (For example, baluma and takete. Which represents a round object, and which an angular? Subjects almost always answer the same, even though both of these words are made up.) Another common tendency is to arrange adjectives in the same order (even in a made-up language). There is also our ability to discern words from non-words. The list goes on.

Evolutionary Road of Language

When it comes to explaining the evolutionary road of language, there are two main strains of thought. Both are centered around the fact that human language is incredibly complex. Indeed, there is nothing even close to it in the animal kingdom.

Theory One (the “Continuity Theory”): Because language is so complex, it cannot have developed suddenly. It must have very gradually developed from our primate ancestors. Thus, primordial “grunts” and “squawks” gradually developed into more precisely vocalized, meaningful words and sentences. Dating for this is extremely wild—perhaps beginning around 2.5 million years ago and culminating in general linguistic “modernity” around 100,000 years ago, at which point different human languages began diversifying. Most linguistic scholars adhere to the Continuity Theory to one degree or other.

Theory Two (the “Discontinuity Theory”): Because language is so complex and unique only to humans rather than other animals, it must have developed suddenly. If it had developed gradually from our primate ancestors, then we would expect to see at least some forms of human-like language among our great-ape “cousins” or among other primates. As such, language must have been a very rapidly developed part of the human condition—perhaps happening around 150,000 years ago.

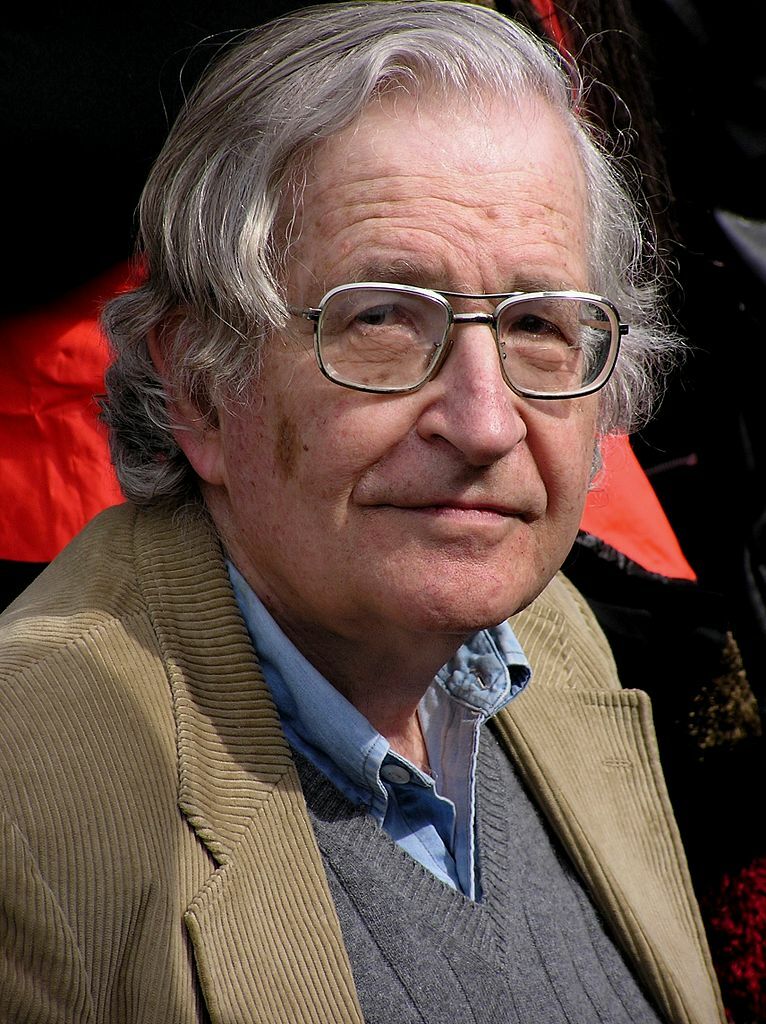

The famous American linguist and philosopher Noam Chomsky adheres to the Discontinuity Theory, believing that a single, swift mutation caused the ability for human language to be realized. He stated in 2000:

[S]ome random mutation took place, maybe after some strange cosmic ray shower, and it reorganized the brain, implanting a language organ in an otherwise primate brain.

Chomsky cautioned against taking this statement too literally, but still insisted it could be a more accurate description of events than other evolutionary explanations. And though his views are generally unpopular, scientists admit that his ideas on language development are being “validated” by new experiments, proving language to be an “innate,” hardwired ability of the human brain.

Within these two theories are a number of other explanations for exactly how language developed—be it initially through gesturing, by replicating sounds of animals or tools, or a development of natural grunts made while heaving objects or getting injured. One quickly learns that on the evolutionary development of language, there is an ocean of theories and very few conclusions. We are left with more unanswered questions than we started with.

Biblical Road of Language

The Bible doesn’t describe an original development of language. Rather, language is shown to be a trait of God Himself. In only the third verse of Genesis 1, we read our first reference to language. “And God said, ‘Let there be light.’ ….” What follows is the account of creation—each feature of our planet being formed at the behest of a divine verbal command.

The Bible describes that animals were created “after their kind.” Humans, though, were not—they were created after the “God kind,” “in our image, after our likeness.” As such, man was given the divine ability to think and translate those thoughts into spoken words. And after creating man and woman, God immediately spoke to them, “Be fruitful, and multiply …” (Genesis 1:28). In Exodus 4:11, God affirms to Moses this point—that He was the creator of man’s linguistic abilities.

As for the written word, the first reference to writing may be in Genesis 4:26 (relating to Adam’s son Seth), which passage can be translated as “to read, to publish the name of the Lord.” Whatever the case, writing is evidently inferred as developing very early in human history.

Another significant biblical point about language is that God allowed man flexibility and creativity in developing his vocabulary, coining new words. This is evident in Genesis 2:19-20, when God brought the animals to Adam “to see what he would call them; and whatsoever the man would call every living creature, that was to be the name thereof. And the man gave names to all …”

The biblical view explains, thus, not only why all mankind (and only mankind) has language, but also why mankind universally shares the “smaller,” unique aspects of language (such as synonyms, antonyms, metaphors, etc).

For the 1,500 to 2,000 years after the biblical account of creation, there is no significant mention of the development of language—until just after the Flood at the tower of Babel. “And the whole earth was of one language and of one speech” (Genesis 11:1). The growing multitudes, after the Flood, gathered in the plain of Shinar in order to establish a powerful, compact civilization and to build a tower that would reach unto heaven—a tower that, later accounts explain, would enable man to survive another flood, and from which man could ascend to heaven and personally challenge any such attempt by God. Verses 6-8 state:

And the Lord said: ‘Behold, they are one people, and they have all one language; and this is what they begin to do; and now nothing will be withholden from them, which they purpose to do. Come, let us go down, and there confound their language, that they may not understand one another’s speech.’ So the Lord scattered them abroad from thence upon the face of all the earth ….

The historian Josephus tells us that God had, through Noah, been spreading out mankind to repopulate the Earth, post-Flood. But mankind defied God’s instructions and congregated together into a close-quarters, city environment in Shinar. God foresaw the rapid development of evil designs between a people of one language living in one place. So He intervened to confound the language, forcing man to spread out around the world with those of his own language.

This explains early major changes in languages and the existence of “language isolates”—languages that have no known connection to or development from other languages. Later, minor developments of language, of course, occurred naturally over time (e.g. the Germanic origins of English). The biblical account explains why language is exclusively human and why it is literally hardwired into our brains and vocal anatomy: because God deliberately designed it as such.

What does archaeology tell us about this cultural universal?

Early Language: According to the Discoveries

According to the biblical account, man has been speaking and writing for around 6,000 years (the full course of his existence). Archaeologists have dated the earliest discovered, generally accepted use of written language to around 5,500 years ago. It is interesting that this is the age of the earliest writings, if humans really had started to evolve in “speaking” 2.5 million years ago, reaching linguistic “modernity” 100,000 years ago—95,000-plus years is a long time to finally get to the point of putting the spoken word down on “paper.”

And it’s not just one, single, isolated culture that began writing some 5,500 years ago. It is from this time (and just after) that several peoples and cultures from different areas in and around the Middle East/Asia start writing—region-wide. In fact, so close are the dates for early writing across certain countries that argument continues (perhaps also for national prestige) as to which language developed first!

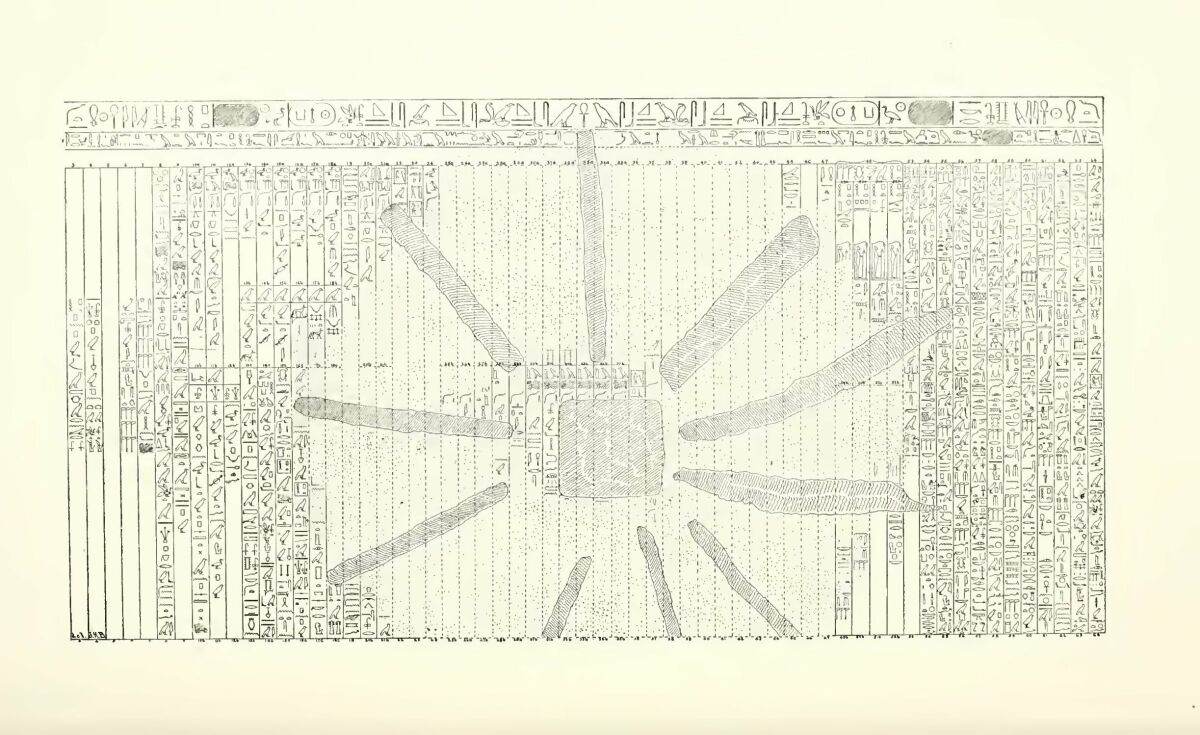

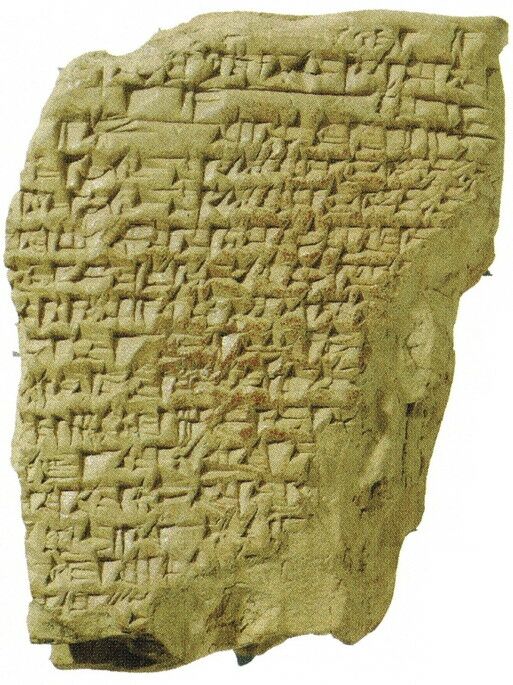

Some of the earliest examples are the Indus script (India, undeciphered, c. 3500 b.c.e.), Sumerian cuneiform (Iraq, 3100 b.c.e.), Proto-Elamite cuneiform (Iran, undeciphered, c. 3100 b.c.e.), and Proto-Egyptian hieroglyphs (c. 3300 b.c.e.). The earliest discovered texts are generally in the form of pictographs—simple images representing certain ideas that gradually morphed into more simple yet abstract signs. (See the image below for the development of the cuneiform script.)

Debate abounds regarding the dating, and even authenticity, of earlier discoveries of writing, such as the European Vinča symbols (dated roughly to 5500 b.c.e.). Excluding these controversial items, the general consensus for writing is that it originated in the fourth millennium b.c.e.

Biblical Account and Archaeology

The Bible first describes language in the context of God speaking in order to create the Earth. An interesting creation myth from Egypt centers around the god Ptah, the Egyptian creator-god of the universe. According to the seventh-century b.c.e. Shabaka Stone, Ptah gave spoken commands in order to bring the world into being and to bring up dry land from the waters that covered the Earth. This account rings very similarly, in this respect, to the earlier Hebrew account—reflecting a similar memory of the origin of the Earth—and claims speech as an already established construct at the start of man’s existence.

The biblical account of the tower of Babel and the resulting development of languages was recorded by various cultures around the world. Variations on the idea of a tower of Babel and confusion of languages can be found in such far-flung places as Korea, Mexico, Kenya, Estonia, Guatemala, Greece and Alaska. These cultures join with the ancient Middle Eastern traditions held by the Sumerians, Assyrians, Chaldeans, Syro-Phoenicians and Hebrews. (Read our in-depth article on the parallel tower of Babel accounts here.) According to biblical chronology, the incident and spreading of languages probably occurred around 2250 b.c.e.

An ancient Sumerian epic, dating to c. 2100 b.c.e., called Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta, tells of dialogue regarding the sending of tribute to build a tower at Eridu in Sumer. (Sumer is the equivalent of the biblical “Shinar,” within which the tower of Babel was built. Additionally, there are further parallels between the city Eridu and the biblical Babel, including a partially completed tower—read here for more information). Partway into the long inscription, we find the following paragraph (emphasis added):

Chant to him … the incantation of Nudimmud: “… the whole universe, the well-guarded people—may they all address Enlil together in a single language! … for the ambitious lords, for the ambitious princes, for the ambitious kings—Enki, the lord of abundance … shall change the speech in their mouths, as many as he had placed there, and so the speech of mankind is truly one.

Here we read, in the context of attempting to build a tower, an incantation to try to cause people to all speak the same language. We see that the “lord of abundance,” Enki, had “placed” many languages among the nations—and this incantation was intended so mankind could work together with one language. Other translations of the text render it of even closer resemblance to the biblical confusion of languages. Here is one alternative translation of the same passage:

Once … the whole universe, the people in unison, spoke to Enlil in one tongue. … Then Enki, the lord of abundance … changed the speech in their mouths, brought contention into it, into the speech of man that had been one.

Whatever the correct original meaning, the connection with the confusion of languages in Genesis 11 is evident. The ruler in this text, Enmerkar, desired the unity of language in order to accomplish his goals—a unity that had once been, but was no longer, due to divine intervention. What is also very tangible is the proximity in date between this text and the biblical chronological date for the tower of Babel episode.

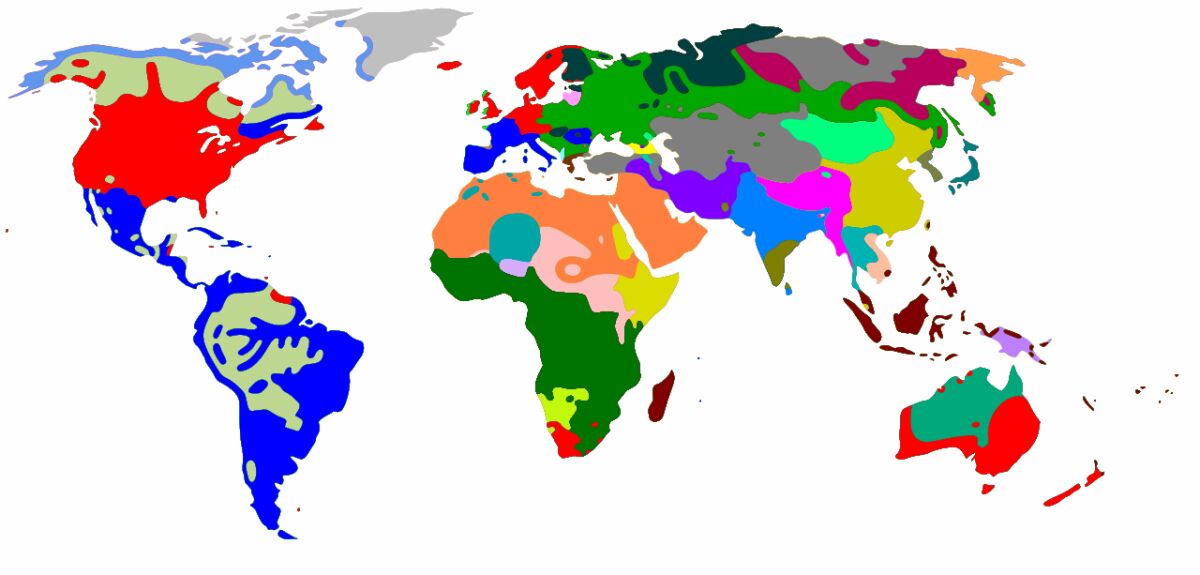

Thus we see the Earth brought back to one language at the time of the Flood, with the single Noahide family. Upon God’s intervention at the tower of Babel, mankind’s language splits into major divisions—perhaps explaining several of the language isolates around the world. From those primary, separate languages, further languages and dialects developed over thousands of years, bringing us to the point today where there are between 6,000 and 7,000 different languages around the world.

Again, these traditions of a “tower of Babel” confusion and spread of languages can be found all over the globe. One could almost be forgiven for calling it a “cultural universal.”

Conclusions

So what does it all mean? As maligned as the biblical account is, it certainly fits the material discoveries. Only deliberate creation really explains how language is hardwired into our systems. It explains how our language is so entirely different and infinitely more complex than that of any animal on Earth, worlds apart from our “closest cousins,” the great apes. The general biblical time frame for man’s existence matches with the general chronology of the earliest archaeological discoveries of writing, stemming from exactly the same parts of the world as mankind is said to have emerged from. The biblical account of the development of different languages, starting at the tower of Babel, is found in different national histories all over the world. What must have happened to trigger the recording of such stories? A common idea points to a common experience. Maybe our forefathers really were dispersed abroad, according to their new languages. Perhaps this historical and cultural mark was left on all mankind as a result. And even the biblical account of the Earth being created by the spoken word—thus inferring language as an attribute of God Himself—even this is paralleled by archaeological discovery!

The evolutionary concept of language, however, is entirely speculative. It doesn’t provide any concrete answers—only further questions. Really, the Discontinuity Theory—the theory that is by far less popular but gaining some validation by scientific linguistic experiments—is more similar to the biblical account.

According to the evolutionary hypothesis, language should be evolving, from its “primitive” forms thousands of years ago, as society “progresses.” Instead, languages around the world have been measurably devolving from higher, complex forms. It’s simply the way of life in the physical world—degradation and degeneration—and the same applies to language. English is a modern, almost comical case in point—the turn from Shakespearean, King James Old English to emoji-riddled text language and barely coherent street slang. Similar examples exist around the world with other languages. Akkadian, the lingua franca of ancient Mesopotamia, is an early cuneiform script that “should” be extremely simple based on its age. It is actually incredibly complex (and only re-deciphered in the 19th century). Modern Hebrew is missing much of the complexity of ancient Hebrew, and is generally a much more simplified language. The natural course is for a language to devolve—not to evolve. Of course, “new” languages inevitably develop, but the profound tendency is for them to devolve.

(Note: A quick mention is here made on the subject of Edenics. This is a small scientific movement providing evidence for the world’s languages going back to one original mother tongue: “Edenic.” Comparing words for various items across languages reveals core similarities—“shadow-like” trace elements pointing back to what the original language of man may have been and sounded like. Researchers in this field have pointed to this “Edenic” language, from which various languages were divided, as being very similar to Hebrew. A thorough text on this subject is The Origin of Speeches, by Isaac Mozeson.)

The Bible has much to say on the history of language. And it even describes the future of language. Zephaniah 3:9 prophesies that in the future, mankind will return to one language, just as in the days following the Flood. But this will be a somewhat different language. It reads:

For then will I turn to the peoples A pure language, That they may all call upon the name of the Lord, To serve Him with one consent.

This verse describes a time following the coming of the Messiah, when mankind will not have the same inventions of evil as at the tower of Babel. The corrupt, devolved languages of our day are to be replaced by a pure language, from which mankind will together serve God with one mind.

The history of language helps prove the veracity of the Bible. Together with other cultural universals (such as marriage, described in our last article in this series), the biblical account of man’s common heritage, going back to the original single created family, is made plain.

Articles in This Series:

Marriage: A ‘Cultural Universal’ in Archaeology and the Bible

Language: A ‘Cultural Universal’ in Archaeology and the Bible

Clothing: A ‘Cultural Universal’ in Archaeology and the Bible