Judahite worshipers in a temple at Tel Arad burned cannabis as part of their ritual worship some 2,700 years ago, new research has revealed. Furthermore, the finds at the site match closely with the reign and practices of Judah’s King Ahaz.

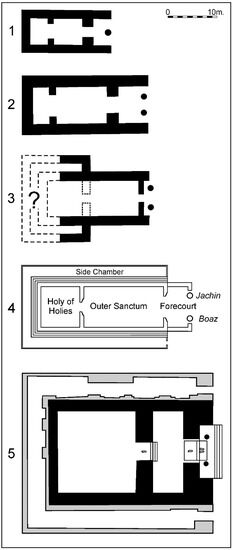

Tel Arad is an archaeological site in Israel’s Negev desert, southwest of the Dead Sea. The ancient hilltop fortress was in use from around the 10th-9th century to the sixth century b.c.e., and is known for its prominent temple. This temple is notable because it roughly parallels the layout of the holy temple in Jerusalem, described in 1 Kings 6. (A number of such temples have been discovered around Israel, pointing to a copy in design of the central temple of worship.)

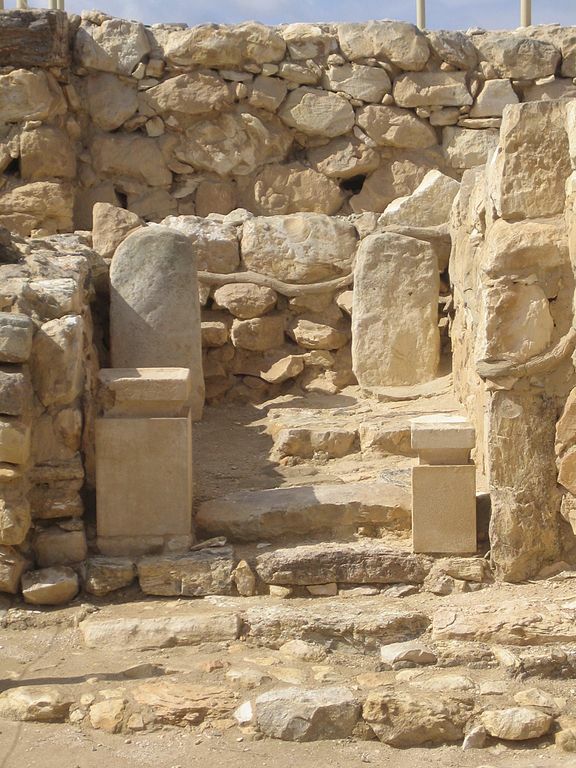

During excavations in the 1960s, archaeologists uncovered the “holy of holies” room of this Arad outpost-temple, which included two limestone incense altars that had been buried at the end of the eighth century b.c.e. The top of these altars contained charred residue of the substances that had been ritually burned on top of them. But the researchers were unable to identify the burned substances—until now.

Frankincense and … Marijuana?

Research conducted by Eran Arie, Baruch Rosen and Dvory Namdar published Friday in a Tel Aviv University archaeology journal revealed the detailed analyses of the substances. The larger of the two incense altars was discovered to have remains of frankincense. This common incense ingredient is mentioned numerous times in the Bible (e.g. Exodus 30:34). This discovery, while unsurprising, is still the first time it has been discovered in an archaeological excavation in the Levant.

The remains on the smaller altar were significantly different. Analysis of the residue on this altar revealed cannabis—including the psychoactive compounds thc and cbn, as well as cbd. This constitutes the first-ever discovery of drug use by the early Israelites. And the evidence at Tel Arad shows they were rather good at burning it.

This is based on how it was burned. The frankincense, on the first altar, had been mixed with animal fat. This allows for burning at the significantly high temperatures needed to release incense aromas. The fuel for the cannabis altar, on the other hand, was found to be animal dung. (Animal excrement is a pretty common fuel for fire, especially in sparse desert environments.) This burns at much lower temperatures, which allows for the best activation and release of the psychoactive compounds, and allows for a slow burn, as for group-inhalation.

The marijuana plant does not have good properties as an incense ingredient. As such, it was evident that this smaller “cannabis” altar was used to induce an ecstatic “high” during worship, in tandem with the main incense altar on which frankincense was burned. In such a manner, the ancient Israelites joined other known surrounding cultures that used ecstatic drugs in ritual worship.

Use in Jerusalem’s Temple?

The researchers speculate that their discovery may indicate that cannabis was an important part of worship at the temple in Jerusalem, positing it as part of the wider “cult of Judah.” The bbc reported that “the findings in Tel Arad suggest that cannabis also played a role in worship at the temple of Jerusalem.” From the Times of Israel: The “discovery also suggests cannabis may have been used in rituals at the temple in Jerusalem.” Haaretz reported that the discovery of drug use showed that “the practice was part of the early history of Judaism.” The inference being that this was part of official, sanctioned, standard worship rites at Solomon’s temple—even beyond that, a part of early Judaism itself. What is the evidence for this?

Due to Jerusalem’s political situation, little from Solomon’s temple has been discovered (besides circumstantial evidence)—certainly no evidence of incense offerings or drug use. As such, archaeologists have looked to other sites around Israel for clues about worship in Jerusalem’s temple. A number of temples are styled in the same manner as Solomon’s, including this one in Tel Arad. The archaeologists thus have inferred that, based on the similarity of architectural layout, there may have been a similarity in rituals. Further, they point out that frankincense (and likely cannabis too) was an expensive item that had to be imported—thus, the use of such items must have been sanctioned and perhaps even imported by the rulership in Jerusalem. In an interview with Haaretz, one of the study’s authors, Dr. Eran Arie, stated: “If the shrine at Arad was built according to the plan of the temple in Jerusalem, then why shouldn’t the religious practices be the same?”

This claim that drug use in Arad’s temple means drug use in Jerusalem’s temple was met with some pushback in the comments sections to articles reporting on the discovery. One Times of Israel reader wrote: “Why should this ‘altar’ have any connection to the temple in Jerusalem? We’re taught that when the temple in Jerusalem was built by King Solomon, private altars became forbidden at the same time. Therefore, even if this site was an altar it wouldn’t have anything to do with the standard Israelite ritual.”

It’s a great point. The Bible clearly spells out and condemns other, pagan temples around Judah, and the type of worship that occurred in them. It prescribes different worship only at the Jerusalem temple. Such scriptures negate this hyper-simplified theory of equivalency between worship at pagan temples and worship at the Jerusalem temple.

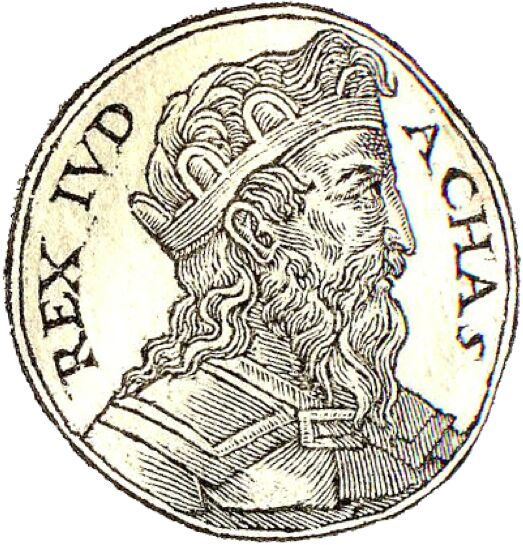

Of course, in the secular world of archaeology, biblical evidence is typically cherry-picked or overlooked in favor of personal opinion. It’s a shame, because missing from the news articles and analyses is how the Tel Arad discovery matches precisely with the biblical account condemning pagan incense-worship during the reign of King Ahaz.

High Places and Incense Offerings

But first, a note on the temple structure itself. It would make logical sense for Solomon’s renowned temple in Jerusalem to have served as a model for copycat places of worship around Israel, like this one. Later in his reign, Solomon himself built bamot, “high places” for the worship of pagan gods (1 Kings 11:7). King Jeroboam created counterfeit places of worship so the northern Israelites wouldn’t travel down to Jerusalem’s temple to worship (1 Kings 12). Pagan “houses of the high places” are mentioned numerous times in the Bible. It is quite likely that the elevated temple at Tel Arad was one such example of these bamot. Furthermore, the Tel Arad temple contained “standing stones” inside its “holy of holies”—another feature linked to high places (1 Kings 14:23); again, a feature completely different from that of the Jerusalem temple.

Scholars have debated the dating of the Tel Arad temple. Some believe that it was built as early as the 10th century b.c.e. If so, this may relate to the high places built by Solomon or perhaps Rehoboam (1 Kings 14:22-23). But the chief evidence shows that the temple was primarily in use for a short 40-to-50-year window: around 760 to 715 b.c.e.

In Bible chronology, the kings of Judah during this period were Uzziah, Jotham, Ahaz and Hezekiah. The Bible describes Uzziah as largely a righteous king, “except that the high places were not removed; the people still sacrificed and burned incense on the high places” (2 Kings 15:4; New King James Version). The same language is used for the reign of Uzziah’s son, Jotham—righteous worship in Jerusalem but the continued burning of incense in the high places by people around the kingdom (verse 35). With this latest discovery, we have clear archaeological evidence that this burning of incense took place—again, contrary to the commanded worship solely in Jerusalem.

But we can get even more specific. The research team that examined the cannabis remains believe that the window of use for these specific Tel Arad altars was even narrower—perhaps within a 10-to-20-year period, circa 735–715 b.c.e. This narrows things down to Judah’s kings Ahaz and Hezekiah (both of these kings have been proven by archaeological discoveries). And the evidence at Tel Arad fits precisely with the biblical account of these kings.

Ahaz and Hezekiah

Following the more “righteous” rulership of Uzziah and Jotham, things take a turn under King Ahaz (circa 742–726 b.c.e.). The Bible records Ahaz as one of Judah’s most pagan kings—to the point of practicing child sacrifice (2 Kings 16:3). He was also prolific in establishing pagan places of worship, with a specific emphasis on incense offerings. “And in every single city of Judah he made high places to burn incense to other gods” (2 Chronicles 28:25; nkjv). Under the reigns of Uzziah and Jotham, worshipers at Tel Arad would have been able to undertake pagan rituals in spite of the leadership and “true” worship at Jerusalem. Under Ahaz, the Bible reveals, they had full royal sanction—to the point that Ahaz made sure every single city had a “high place” and incense altars. And the archaeological evidence points to the Tel Arad incense altars being established at this very time!

Such was Ahaz’s penchant for burning “incense” that he even had the brazen incense altar taken out of Jerusalem’s temple and placed outside for “personal use” (2 Kings 16:15, New English Translation; the Hebrew translated as “personal use” or “to inquire” is uncertain, but in this case, given the recent discovery, we can only imagine what he might have been burning).

Following Ahaz’s death, his son Hezekiah became king (circa 726–697 b.c.e.). “And he did that which was right in the eyes of the Lord …. He removed the high places, and broke the pillars …” (2 Kings 18:3-4). Hezekiah actually had the Levites and priests scrub clean Jerusalem’s temple, altars and equipment (2 Chronicles 29). Why such a deep clean if worship at Solomon’s temple was simply the same as anywhere else? Could it have been, among other things, the result of improper products being burned on the incense altar?

Following the purge of Jerusalem’s temple, Hezekiah extended his national “cleansing” across the entire country—and even up into the northern kingdom of Israel (2 Chronicles 31:1). The Bible notes the incense altars that had been set up all around the land. “And they arose and took away the altars that were in Jerusalem, and all the altars for incense took they away …” (2 Chronicles 30:14). This purge was so thorough that even an Assyrian general knew about it (2 Chronicles 32:12).

Archaeological evidence for Hezekiah’s “cleanse” is abundant. Particularly vivid is the destruction of a pagan altar-room at Lachish, and the installation of a toilet inside it, in order to symbolically desecrate the place of worship (see also 2 Kings 10:27).

And what do we find at Tel Arad? Dating to this very same period, circa 715 b.c.e., we find the worship at these two altars stopped. They had been laid down on their sides and buried!

They had not been smashed—perhaps this was the result of a sympathetic priest/addict begrudgingly carrying out orders to scrap the altars. Nonetheless, during this early part of Hezekiah’s reign, worship at these altars stopped. And so, quite remarkably, both the start and end of this altar use at Tel Arad attests to the accuracy of the biblical account.

The researchers are right: Tel Arad cannabis-worship did indeed have royal appointment—but the textual evidence shows it was strictly at this precise window of time. And as they point out, frankincense and cannabis were expensive items that had to be imported to the city from elsewhere. As Arie told Haaretz, “Importing cannabis and frankincense was a big investment that could not be made by some isolated group of nomads. It required backing from a powerful state entity.” The Bible reveals precisely which monarch actively facilitated its use.

Unfortunately, the researchers couldn’t point to this exciting evidence of the biblical account because it reveals that the Tel Arad worship was a pagan sideshow, diametrically opposed to the officially prescribed worship in Solomon’s temple. It would have undermined the “exciting” speculation that Solomon’s temple was a pot house.

Cannabis in the Bible?

But the speculation continues. From Haaretz: “[I]f the ancient Israelites were joining in on the party, why doesn’t the Bible mention the use of cannabis as a substance used in rituals, just as it does numerous times for frankincense?” It continued:

One possibility is that cannabis does appear in the text but the name used for the plant is not recognized by researchers, Arie says, adding that hopefully the new study will open up that question for biblical scholars.

The wealth of biblical evidence forbidding the Tel Arad worship is overlooked—but what is highlighted is that the Bible may contain unknown references to cannabis?

Examining this question in full would require its own separate article. But here are a few points.

As Arie points out, “the name used for the plant is not recognized by researchers.” The Bible carefully defines four specific ingredients to be blended together in specific measurements and burned on the incense altar. Failure to follow these instructions resulted in banishment and even death (Exodus 30:38; Leviticus 10:1-2). The main incense altar at Tel Arad only had one of these ingredients—frankincense—so even in this manner, worship at the site was completely opposite to that prescribed for Jerusalem. Exodus 30:34-35 read:

Take unto thee sweet spices, stacte, and onycha, and galbanum; sweet spices with pure frankincense; of each shall there be a like weight. And thou shalt make of it incense, a perfume after the art of the perfumer, seasoned with salt, pure and holy.

There is some debate as to the precise translation of these biblical ingredients. Still, there is no remote indication or link with cannabis. The historian Josephus, who lived at the time incense offerings were being made in the Second Temple, described these ingredients. No links to drugs. The ingredients are expounded on in ancient rabbinical literature. Again, no links.

What’s more, cannabis is well-known in ancient literature dating to the First Temple period and even earlier. The drug is known from Egyptian text, Greek, Assyrian, Babylonian, Persian, Scythian, Arabic, Sanskrit and Chinese, all in and around the biblical time period. Again, no links to this biblical worship.

The Bible highlights very clearly that the incense was not for any personal effect or pleasure. “[T]he composition thereof ye shall not make for yourselves; it shall be unto thee holy for the Lord. Whosoever shall make like unto that, to smell thereof, he shall be cut off from his people” (verse 37-38). The substances burned before the Lord were not for the “benefit” of the worshipers in any way, shape or form. It was solely to be incense for God.

As was admitted by the Tel Arad research, cannabis does not have good incense properties, and “the Bible only relates to incense for its agreeable fragrance.” The very fact that there were two altars at Arad—a cannabis altar and a frankincense altar—shows the necessary separation in use, even down to how it is burned—one for the smell and one for the “high.” But the Bible quite clearly and categorically mandates only one incense altar, with one set of blended ingredients to be burned together. Anything else, and “he shall be cut off from his people.” Or dead.

What the Bible does clearly and repeatedly mention, and warn against, are the mind-altering effects of wine (e.g. Proverbs 23:29-32; 31:4-6). And the Nazarite class, dedicated entirely to the service of God, was entirely forbidden from drinking it (Numbers 6). It was forbidden for priests to drink alcohol “when ye go into the [tabernacle], that ye die not … that ye may put difference between the holy and the common …” (Leviticus 10:9-10). “Neither shall any priest drink wine, when they enter into the inner court [of the temple]” (Ezekiel 44:21).

Yet we are led to believe that smoking cannabis in the holy of holies of the Tel Arad temple is a model for Jewish worship in Solomon’s temple, and may even be endorsed in the Bible by some as-yet hidden biblical terminology?

Archaeology ‘Highs’ and Lows

In “Uncovering the Truth,” aiba office manager Brent Nagtegaal wrote about the recent discoveries made at a pagan temple in Tel Motza. It was another case of remarkable archaeological corroboration for the biblical account—but again, unfortunately, spun on its head by the lead archaeologists and painted widely (and erroneously) as evidence against the Bible. In that case, conclusions were based on mere assumptions of the biblical text as opposed to careful analysis of the scriptures. As Nagtegaal wrote:

It is a sad fact that there is a lot of “fake news” in the world of biblical archaeology. When reading about a new archaeological discovery, we cannot casually accept the media’s interpretation, especially if it discredits the Bible. Don’t take for granted that the experts are always right. Always check the actual facts, and consider them objectively alongside a thorough reading of the biblical text. When we take this approach, we will often be surprised to learn that many of the discoveries that supposedly “disprove the Bible” actually do the opposite.

It’s the same story with the Tel Arad temple. It is indeed a remarkable discovery that closely parallels the biblical text from several different angles. Unfortunately, as so often happens, that textual corroboration is overlooked or completely contradicted where it matters, in favor of personal theories. And then those theories are “bolstered” by indications that there may be evidence in the Bible that we haven’t yet discovered.

But with this fascinating new discovery from Tel Arad, demonstrated through some stellar archaeological and molecular research, we have everything right in front of us. We have the discoveries “on the ground.” And we have the biblical account. And it just so happens that they fit hand-in-glove, affirming the accuracy of the scriptural record and painting an ever clearer picture of King Ahaz’s hedonistic reign and the righteous reforms of King Hezekiah.