Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Gath

Mighty Gath: Home of the Philistine giants, the legendary “capital city” of the Philistine pentapolis. But was it just a mythical city? Archaeology has been providing remarkable corroboration of the biblical account of this key city and thorn in ancient Israel’s side.

The original city of Gath has been identified with the modern-day site of Tell es-Safi. While other sites have been speculated as being Gath, none have fit the bill quite as well as Tell es-Safi. And recent archaeological excavations at the site have helped to greatly affirm the legitimacy of the site as the Gath of the Bible.

In this 10th installment of our “Bible’s Buried Cities” series, we compare the facts on the ground with the biblical account of this infamous Philistine city.

Gath: City of Giants

Goliath certainly has to be the most renowned Philistine, and he hailed from the city of Gath. He was not the only figure of sensational proportions to live there, however. The city was already known, at the time of the Israelite conquest of Canaan, as a residence of “Anakim,” or “giants” (descendants of Anak, the giant). Gath is listed in 2 Samuel 21:15-22 as the home of four other specific warring giants, aside from Goliath, all of whom were killed by the Israelites during the lifetime of David.

In excavations during the summer of 2016 at Tell es-Safi, a massive city wall and huge entry gate were discovered at the city. As stated by the site’s director, the gate is one of the largest ever found in Israel. According to the biblical account, King David himself would have been familiar with the gates of Gath—while on the run from Saul, he sought refuge in the Philistine city. Upon realizing that the Philistines suspected who he was, David, fearing for his life, feigned madness, drooling and scratching marks into the city gate (there is a high likelihood that this was the same gate structure found at Tell es-Safi—cities rarely had more than one main entry gate). David ended up being thrown out of the city, thankful to escape with his life (1 Samuel 21).

Along with the mighty gate, other architectural features were discovered by archaeologists, including an impressive fortified wall, various buildings, an iron production facility and a temple. Gath’s fortifications date to the period of the Israelite monarchy—the time of King David and beyond. But before we delve further into this history, we must first take a step back to the time of Samson.

Samson’s Pillars

Samson, the infamous Danite judge of Israel (who ruled during the 12th century b.c.e.—the period of the judges), was known for his divinely imbued, superhuman strength. His was a continual struggle against the belligerent Philistines, made all the more difficult by his affinity for Philistine women (the most notable of whom was Delilah). His last act—the one that resulted in his death—was to collapse a massive Philistine temple onto himself and 3,000-plus Philistine lords and worshipers. He accomplished this by pushing apart two large central pillars that supported the building (Judges 16).

There is some exciting archaeological support for this incident. Archaeologists have discovered that the temple plan—of having two central supporting pillars—was indeed a well-established Philistine architectural feature. While the biblical incident happened in a city of Gaza, temples of this layout have been found in both Gath and Tel Qasile. The pillars would have been close enough for a tall man to spread himself between. This not only supports the biblical story, but also provides support for the account having been written when it says—rather than long afterward as some sort of “imagined” history.

Sometime in the century following this event, the Philistines captured the ark of the covenant from the Israelites. They took it back with them as a war trophy—but wherever they brought the ark, illness and death soon followed. One of the cities they brought the ark to was Gath (1 Samuel 5), before returning it to Israel.

Goliath’s Mates

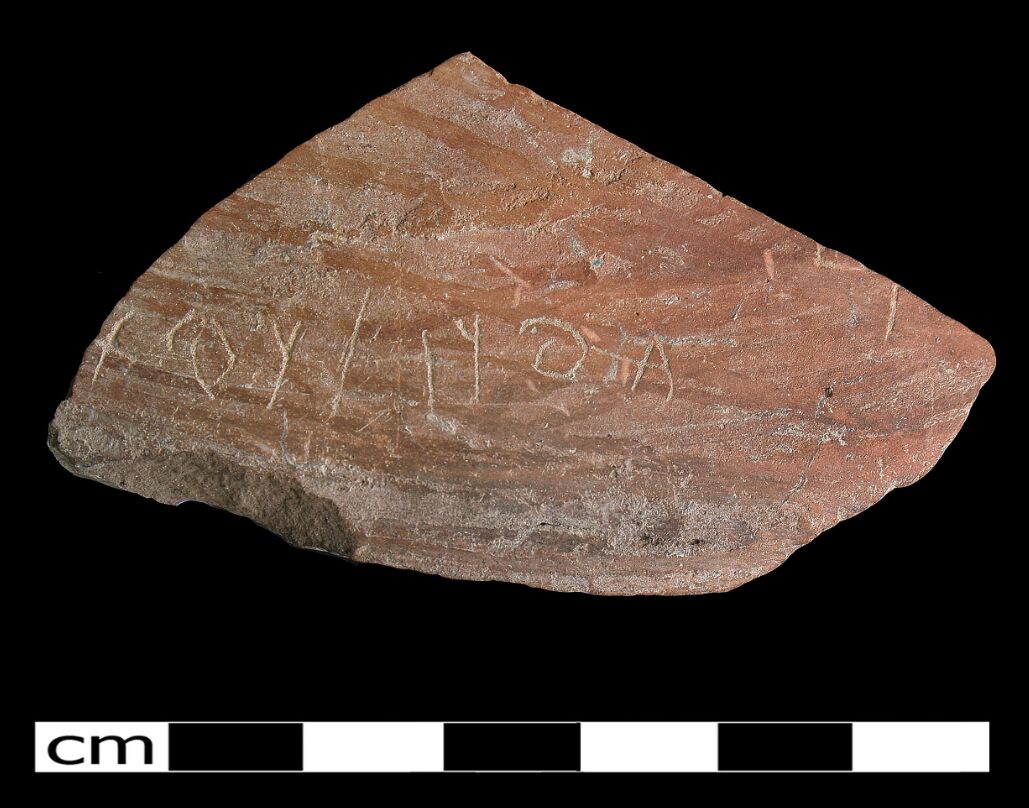

Moving forward in history, we come to the time of David and Goliath. Goliath would have grown up in Gath c. 1050. While the man himself has not been attested to archaeologically, something can be said for his name. Two inscribed potsherds have been found at Gath, dating to the 10th to late 9th century b.c.e., making these the earliest Philistine inscriptions ever discovered. They bear two names of linguistic link to Goliath’s—Alwat and Wlt. Of course, our Anglicized version of “Goliath” is much different from the original—pronounced in Hebrew as Galyat. These names all show Indo-European roots, rather than Semitic roots like the Canaanite and Hebrew names. This confirms the distant Mediterranean origins of the Philistine peoples and lends support to the biblical accuracy of the story of Goliath, authentic in name.

It is very possible that Goliath was known by these two men. And besides this ancillary linguistic evidence, there is further archaeological corroboration for the biblical account of Goliath. A fortress where the Israelite army most likely was based for this David vs. Goliath battle has been found.

David continued to have further dealings with the city of Gath long after the death of Goliath. As stated above, he fled to this city to escape from Saul, only to be identified as Goliath’s killer, leading David to feign madness in order to convince the Philistines they had misidentified him and to let him go. Later, David returned to Gath while still on the run from Saul, having been granted asylum by the Philistine ruler Achish (1 Samuel 27; there is also a “King Achish” of Gath described during the reign of Solomon—it appears this is a separate individual). Here again, there is corroboration for this Philistine name.

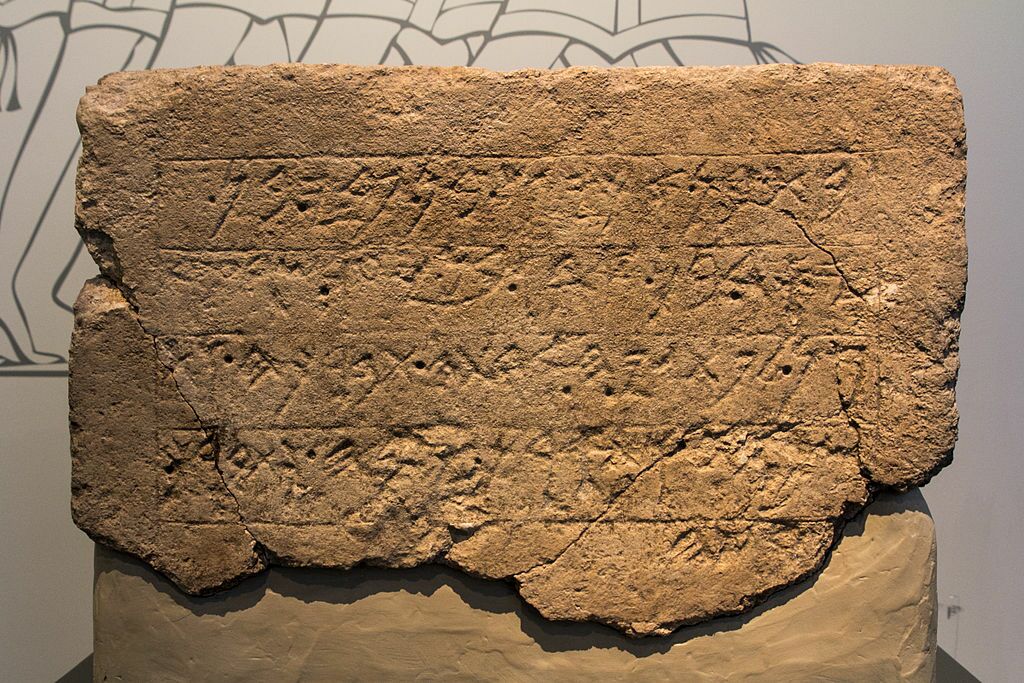

Dating to the seventh century b.c.e., a large stone tablet was discovered at Gath’s sister city Ekron. It contains a lineage of five rulers. One of the rulers named is Achish. This must have been a common Philistine name, and like Goliath, Alwat and Wlt, it is not Semitic. One proposal is that it is related to the word “Achaean” (meaning “Greek,” or specifically, “Achaean Greek”).

Wars of Gath

This Philistine city certainly has experienced its share of violence and bloodshed. The Hebrew name of the city, pronounced Gaht, means “winepress,” a word sometimes used in the Bible to describe bloody events.

The very first violent act at Gath, recorded in the Bible, goes all the way back to the time of the patriarchs—specifically, to the time of Jacob’s grandson Ephraim. Ephraim’s sons attempted a cattle raid on the men of Gath. The Ephraimite men were, unsurprisingly, killed in the act by the Gittites (1 Chronicles 7). (On a side note, this chapter describing Ephraim’s children actually gives evidence for Israelites still living, owning and operating land in Canaan during the sojourn in Egypt.)

While there was an initial level of friendship between the early Philistines and the early patriarchs (i.e., Abraham—Genesis 21), the Philistines were generally known as fierce, war-mongering people. In fact, the very reason God had the Israelites enter Canaan the long way around—from the east, across the Jordan River—was because He didn’t want the Israelites to run into these fierce warring people and thus desire to return to Egypt (Exodus 13:17-18).

The Philistines were especially belligerent during the reigns of the kings of Israel and Judah. Wars were constantly fought, and land continually switched hands back and forth. David’s once-good relationship with the people of Gath deteriorated, and he fought against the city, a battle in which a particular 12-fingered and 12-toed giant was killed (2 Samuel 21). 1 Chronicles 18:1 states that King David actually “took Gath and its towns” right out of the hands of the Philistines, claiming the entire Philistine region for Israel. David’s grandson, King Rehoboam, actually rebuilt the city of Gath, indicating that it was in Israelite hands during his reign as well (2 Chronicles 11:8; though at the very least a regent king, Achish, ruled over the city during the reign of Solomon—1 Kings 2:39-40).

During the ninth century b.c.e., King Hazael’s Syria was a mortal enemy of Israel—and so too, as it turns out, of the Philistines. 2 Kings 12:18 describes a conflict between this king and Gath, in which Hazael devastated the city and took it for himself:

Then Hazael king of Aram went up, and fought against Gath, and took it; and Hazael set his face to go up to Jerusalem.

Abundant evidence of this biblical conflict has been discovered in excavations at Tell es-Safi. The first major discovery at the tell was a man-made trench surrounding most of it: 2.5 kilometers long, 8 meters wide and more than 5 meters deep, encompassing the city on three sides. This feature turned out to be a massive siege system that was dug by an attacking army, making it virtually impossible for citizens to escape the city. An earthen ramp up to the city was also found. (This is the earliest known siege system in the world.)

The feature was carbon-dated and pottery-dated to the early 800s b.c.e.--precisely the time frame for Hazael’s siege of the city. Together with the dating of the siege system, evidence of a massive destructive fire was found on the tell, relating to the same event. This proves that the besieging army had been successful in breaking through and conquering the city—again, just as the Bible claims.

Gath vs. Uzziah: War and Earthquake

During the following eighth century b.c.e., a Judahite king named Uzziah assumed the throne at the young age of 16. As an (initially) obedient king before God, he presided over a time of great prosperity for the kingdom of Judah. One of his first-described acts was to go to war with Gath, a successful campaign against the Philistine city in which his men broke through the city walls (2 Chronicles 26:6). Uzziah was also victorious against the Philistines in the wider region, including the city of Ashdod. To read about the general archaeological evidence for King Uzziah, check out our article on the subject here.

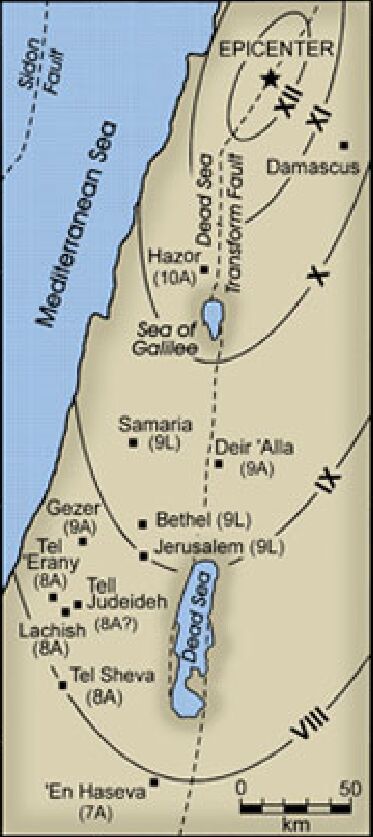

Toward the end of Uzziah’s reign, though, things fell apart for the successful king. He attempted to usurp the priests in offering forbidden incense in the temple. He was immediately smitten in the head by leprosy. Further, right around this period, a massive earthquake rocked the Levant. (Many, including Josephus, attribute this earthquake to Uzziah’s sin in the temple.) The earthquake is mentioned by the prophets Zechariah and Amos, and was evidently so significant and memorable that Amos dated his book of the Bible to this event. Incredibly, vast amounts of earthquake evidence have been found throughout the region of Judah, Israel, Moab and Philistine—notably Gath.

At Tell es-Safi, a large 20-meter-long wall was discovered near the summit of the city. Scientists showed that the wall had been laterally moved about two meters during an earthquake, and then toppled. Seismologists have agreed that this shift could have only been caused by a massive earthquake.

The earthquake damage in Gath, and the parallel sites in the Levant, dates to c. 760 b.c.e., right around the latter third of Uzziah’s reign. Tilted walls, collapsed floors and more have been found testifying to this earthquake. So great is the amount of catastrophic evidence that scientists have been able to determine the epicenter was likely in Lebanon, and that its strength was probably around a magnitude 8.2, with a Modified Mercalli intensity of 9. Geologist Steven Austin, Ph.D., writes (emphasis added):

[This event] appears to be the largest yet documented on the Dead Sea Transform fault zone during the last four millennia. The Dead Sea Transform fault likely ruptured along more than 400 kilometers as the ground shook violently for over 90 seconds! The urban panic created by this earthquake would have been legendary.

There’s no telling the death toll from such a massive earthquake. We do have data, though, from earthquakes of somewhat lesser intensity that hit the region, from which we can get a loose picture. Two intensity-8 earthquakes occurred on the Dead Sea Transform fault—one in 749 c.e., killing 100,000 people, and one in 526 c.e., killing 255,000. And remember, the 760 b.c.e. earthquake was another intensity level higher! So not only would this earthquake have remained deeply ingrained in the minds of the Israelites, but also in the history and tradition of the Philistines.

Gath to Today

After the eighth century b.c.e., Gath fades from biblical view. It continued to be occupied throughout history, and in the 12th century c.e. a Crusader fortress Blanche Garde was built at the site, named after the white chalk cliffs of Gath. As in the biblical history of Gath, the site would change hands back and forth, this time between Christians and Muslims. Intriguingly, King Richard i of England (1157–1199) was almost captured near Gath. (He also was responsible for the rebuilding of the site.) The Itinerarium Regis Ricardi, said to be a first-hand account, relates the following:

[K]ing Richard with only a small following was going from our camp towards the casal of Blanche-garde, to lay an ambush for the Saracens, he turned back owing, as it is believed, to some divinely sent instinct that warned him of his peril. And lo! at that very hour two Saracens, who had fled to him, told him how Saladin had a little before despatched three hundred chosen warriors to Blanche-garde, whither the king had intended to go.

In 1948, Gath, or Tell es-Safi, was conquered by Israel, and the area has since become a national park. Today, Tell es-Safi is under regular excavation. The team will “hit the ground” again this summer. You can check out their work on this excavation blog.

Archaeology has uncovered a plethora of not only artifacts that help prove the biblical account, but also entire cities. Cities we have covered in this series, like Jericho—where there is evidence that the walls really did “come tumbling down”; Khirbet Qeiyafa—the likely staging point of the battle between David and Goliath; Hazor—the Canaanite city that “ruled them all”; Megiddo—the region of perpetual bloodshed, mankind’s battlefield; Hebron—city of the patriarchs; Gezer—the “gift of Egypt”; Lachish—Judah’s mighty city, second only to Jerusalem; Dan—the center of pagan Israelite worship; and finally, Jerusalem—the center of everything, the eternal city.

For more information specifically about the Philistines, read our article Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Philistines.

The more we dig, the more the Bible comes to life.

Articles in This Series:

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Ai

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Azekah

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Beersheba

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Beth Shean

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Beth Shemesh

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Dan

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Ekron

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Gath

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Gezer

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Hazor

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Hebron

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Jericho

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Jerusalem

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Khirbet Qeiyafa

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Lachish

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Megiddo

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Mizpah

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Samaria

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Shechem

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Shiloh

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Sodom

Videos in This Series:

Touring the Bible’s Buried Cities: Gezer