“The book of Esther … is a free composition, not a historical document. Its fictional character can be illustrated by many examples …. [A]rtificialities are clear …. There are many exaggerations … sarcastic implausibilities … and huge ironies.”

These are not the words of a secular scholar in a source-critical journal article. This is the introduction to the book of Esther in the New American Bible (nab) and New American Bible Revised Edition (nabre)—the popular translation of the Scriptures for liturgical and personal use by Catholics in the United States. The Jerusalem Bible (another popular translation) opens with a similar introduction: Although Esther bears “the literary form of historical stories, the events … are not attested from other sources and … treat the facts of history and geography with a good deal of freedom.”

The assessment is even more grim from the other side of the Christian spectrum. In the opinion of Protestantism’s founding father, Martin Luther: “I am so great an enemy to the second book of the Maccabees, and to Esther, that I wish they had not come to us at all” (Table Talk, published 1566; emphasis added throughout).

From a Jewish perspective, the book of Esther could hardly be afforded more importance. One of Judaism’s highest-esteemed rabbis and philosophers, the 12th-century Maimonides, esteemed the book of Esther as second to the Torah itself. The events of this book were accorded as historical by the first-century Jewish historian Josephus (as recounted in Antiquities of the Jews 11.6)—the book numbering among those others “which contain the records of all the past times, which are justly believed to be divine” (Against Apion 1.8).

Even still, some religious Jewish leaders have taken issue with the book. Rabbi Samuel Sandmel described Esther as a “fictional piece” that contains “farcical” details; like Luther, Sandmel would “not be grieved if the book of Esther were somehow dropped out of Scripture” (The Enjoyment of Scripture).

Among those dismissive of the historicity of Esther, theories abound for the book’s purpose and message. Some believe the story is artificially modeled after the Moses-Exodus account, against the backdrop of the Persian court. Others believe it to be a creative retelling of the Mesopotamian gods Marduk (Mordecai) and Ishtar (Esther) exerting their supremacy in Persia over the Elamite god Humban (Haman). More generally, the book is considered by scholars as a “novella” in the “wisdom literature” genre—often compared to the likes of One Thousand and One Nights—a biblical text in which “there may be a core of historicity,” a “kernel of truth,” but one thoroughly embellished by “layer upon layer” of coloring (Carey Moore, “Eight Questions Most Frequently Asked About the Book of Esther”). Many scholars consider Esther a complex aetiology (mythologized backstory) for explaining the otherwise-obscure origins of the Purim holiday.

Esther creates an unusual predicament. Often, when it comes to biblical studies, the further back into the past the account is set, the more it is treated with skepticism. Ironically, the book of Esther—one of the latest chronological accounts in the Bible—is one of the most historically disputed books in the canon.

Is the book of Esther fact or fiction? Can we even know?

Setting the Scene: A Brief Overview

The biblical story of Esther is likely well known to the reader. Set in Persia, the book opens with King Ahasuerus hosting an immense festival at his Shushan palace. The king demands his wife, Queen Vashti, attend the party so he can parade her beauty. But the queen refuses, humiliating the king and resulting in her banishment.

King Ahasuerus needs a new wife, and Persia needs a queen. After careful vetting, a candidate is found in the Jewess Hadassah, also named Esther, who was raised by her older cousin Mordecai, an official in the Persian courts (see sidebar about Mordecai at the bottom of this article).

Ahasuerus later promotes the wicked Haman “above all the princes” in Persia (Esther 3:1). This is when the trouble begins. When Mordecai refuses to prostrate before him, Haman—recognizing Mordecai’s Jewish heritage—“sought to destroy all the Jews that were throughout the whole kingdom” (verse 6). He manipulates the king into issuing a decree against a “certain people” who do not “keep … the king’s laws” (verse 8)—and being granted the king’s seal, Haman declares the extermination of all Jews on the 13th of Adar. Mordecai discovers the plot and beseeches Queen Esther—her Jewish identity to this point still disguised—to intercede on behalf of her people.

Esther is granted an audience with the king and organizes a great banquet in honor of the king and Haman. Following this banquet, Esther requests another. Haman leaves filled with pride but also seething with hatred for Mordecai; he constructs large gallows, anticipating Mordecai’s destruction.

At the second banquet, Esther abruptly informs the king about Haman’s plot to kill her people. The next day, Haman is hung on the gallows he had prepared for Mordecai. But a Gordian challenge remains: Persian law means King Ahasuerus cannot rescind the earlier decree demanding the destruction of the Jews. He does, however, issue another decree, one that demands that all Jews defend themselves against any individuals implementing the first decree. This solution is not without bloodshed, but genocide of the Jews is prevented.

The book ends with Esther and Mordecai instituting the 14th of Adar as a day of salvation, celebration and feasting. “Wherefore they called these days Purim …. And the commandment of Esther confirmed these matters of Purim; and it was written in the book” (Esther 9:26, 32).

It’s a riveting story. But is it true?

Ahasuerus and His Empire

Intriguingly, modern scholars broadly agree on one core detail in Esther: the identity of the Persian king. The biblical Ahasuerus is widely recognized as Xerxes i (also known as Xerxes the Great), who ruled the Persian (Achaemenid) Empire from 486 to 465 b.c.e.

At face value, the names could hardly be more different—Ahasuerus and Xerxes. But we are dealing with extremes on both ends of the linguistic spectrum. On the one hand, Ahasuerus is a somewhat fraught English transliteration of the Hebrew pronunciation Achashverosh (the guttural “ch” pronounced as in loch); on the other hand, the popular names used for Persian kings (i.e. Xerxes) are actually transliterations from Greek, not Persian. The Hebrew pronunciation of this king’s name is actually quite close to the original Persian pronunciation of Xerxes’s name, rendered phonetically as Khshayarsha. Furthermore, over the last century, ancient Aramaic documents discovered in Elephantine, Egypt, reveal an Aramaic spelling of Xerxes’s name to be אחשירש—virtually identical to the Hebrew spelling of Ahasuerus, אחשורוש.

Historically, there has been some debate about the correct Persian king of Esther. Other popular candidates, based in part on perceived name-similarities (with the Greek variants), have been either Artaxerxes i (465–424 b.c.e.) or Artaxerxes ii (404–358 b.c.e.). These rulers’ original Persian names, however, are significantly different from the name of the king found in Esther; also, Artaxerxes’s entirely different name (Hebrew Artachshasta) is used 15 times throughout the books of Ezra and Nehemiah (referring to Artaxerxes i), alongside and in distinction to the name of our Ahasuerus (Ezra 4:6). Of additional note is the fact that the territory of Egypt was lost during the reign of Artaxerxes ii (compare Esther 1:1). Further disqualifying these later kings is the fact that throughout their reigns the Jews had significant favor (as the books of Ezra and Nehemiah attest) and would therefore not have found themselves facing the same existential threat described in Esther.

The book of Esther, then, set during the early part of the reign of Xerxes i, fits with that of the identically named, powerful emperor Xerxes, who presided over a domain spanning from India to Cush (Esther 1:1), ruling from his royal palace at Susa (verse 2; Elamite Shushan, identical to the biblical Hebrew “Shushan”).

Unfortunately, this is where the historical parallels are often seen to stop—again, in the muted words of the nab and nabre, the account being only “loosely based on Xerxes.”

127 Satrapies?

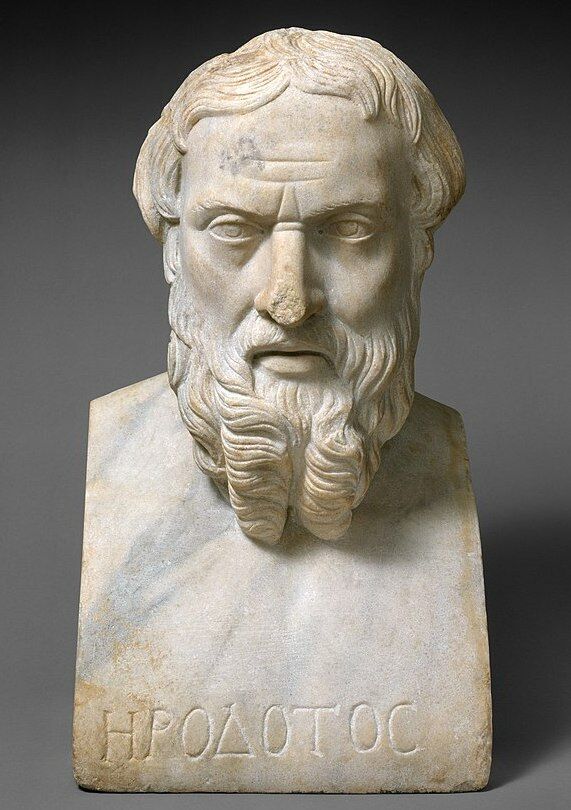

One of the first issues of contention relates to the large number of geographic divisions assigned to the Persian Empire in Esther 1:1. The biblical text identifies 127 distinct divisions of the empire—often assumed to refer to the standard Persian division of “satrapies.” But this is six times more than the number of satrapies recorded by Herodotus, the fifth-century b.c.e. Greek historian, who counts just 20 satrapies during the reign of Xerxes’s father, Darius the Great.

Yet on its face, 127 is an oddly specific number. Furthermore, we can determine from internal evidence within the book of Esther itself that this figure is not referring to “satrapies”—rather, the number is referencing smaller provincial divisions.

“[T]he Hebrew word for provinces used here, medinot, in the Hebrew Bible mainly refers to small districts,” wrote Iranian history expert Morteza Arabzadeh Sarbanani in his 2023 article “The Book of Esther as a Source for Achaemenian History.” “[I]n Esther 3:12, the author makes a clear distinction between ‘the king’s satraps’ and ‘the governors over all provinces’”—the latter word matching that used in the introduction to Esther. “This suggests the ‘provinces’ in Esther 1:1 are not equivalent to the satrapies but the smaller divisions that comprised the satrapies.”

French historian Gérard Gertoux concurs, noting that during the time of Xerxes, the number of satrapies would have likely increased to around 30, and based on an average subdivision, “there were more likely to be around 120 provinces (30 satrapies multiplied by four provinces in each satrapy)”—a tidy fit with the 127 provinces mentioned in Esther 1:1 (“Queen Esther, Wife of Xerxes: Fairy Tale or Real History?”).

Arbitrary Dates?

Another interesting, immediately apparent peculiarity in the book of Esther are the very specific timestamps recorded. The snubbing of Ahasuerus’s initial wife, Vashti, takes place during a long festival at Susa “in the third year” of the king’s reign (Esther 1:3). The story then picks up with the king several years later, “in the tenth month, which is the month Tebeth, in the seventh year of his reign” (Esther 2:16), when the young Esther is brought before him.

The specificity of this time frame is striking. Furthermore, no literary reason is given for this three-to-four-year gap in the first two chapters of the book. What could be the reason?

There are some rather remarkable synchronisms with the reign of Xerxes i (again, whose reign began in 486 b.c.e.). Regarding the first timestamp—the festival of the third year—Sarbanani notes a “loan document from Susa … dated to the third year of Xerxes’s reign confirm[ing] that he was in Susa at that time. We also know that Xerxes had subdued the Egyptian rebels by January 484 b.c.e., therefore, the feast mentioned in the book of Esther may have been a celebration of Xerxes’s victory over Egypt.” The notion that this was a celebration of a military victory is supported by the fact that the first-mentioned guests among the palace nobles are military leaders (Esther 1:3).

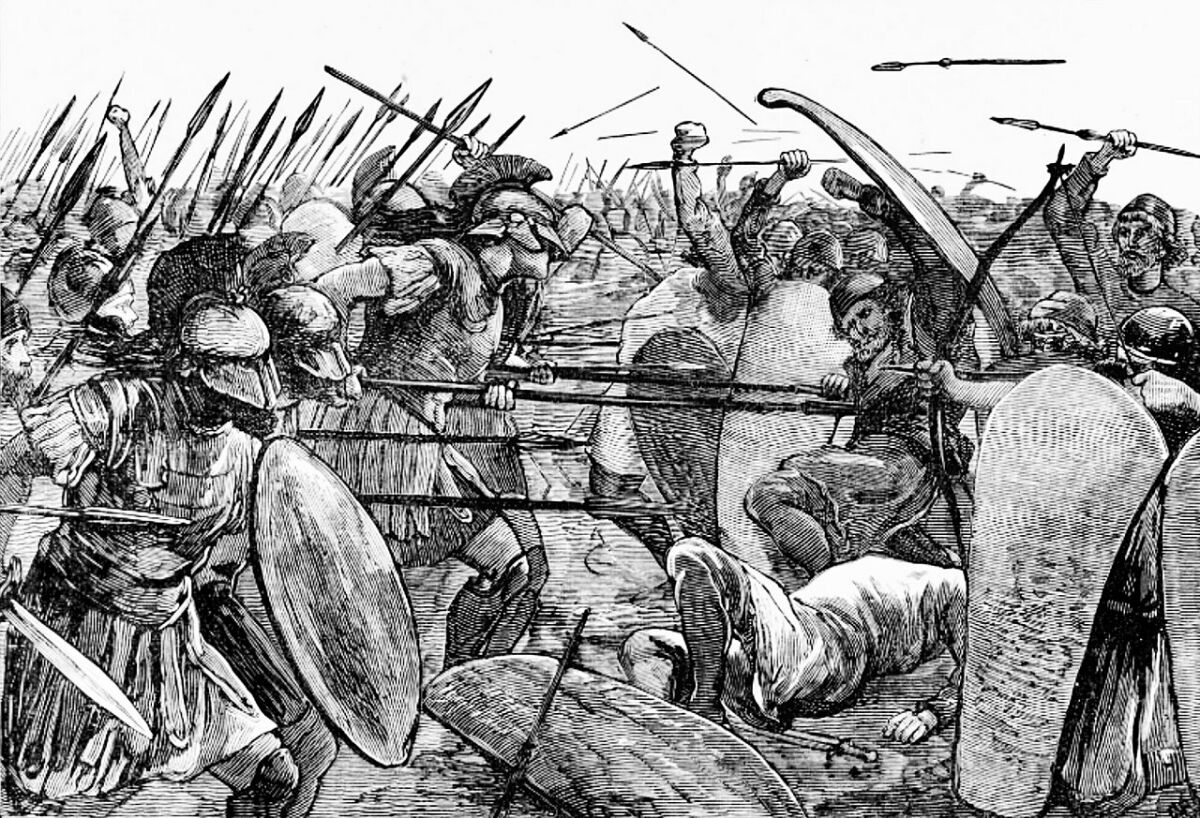

What about the narrative gap between this event and the king reemerging in his seventh year (479 b.c.e.)? The significance of this time period can easily be overlooked. Yet this is when Persia’s king was away on his campaigns against Greece!

Xerxes began preparing his army, which included the combined forces of 46 different nations, for a major invasion of Europe in 481 b.c.e. The campaign that followed (480–479 b.c.e.) is known as the “Second Persian Invasion of Greece” and included such famous battles as that of Thermopylae (of Spartan fame), Salamis, Plataea and Mycale. Ultimately, this campaign proved devastating for Xerxes, who personally led his troops—meaning that he was away from the Persian court until his seventh year as king.

Dr. William H. Shea summarized: “Xerxes left [from his campaign] for Susa … approximately the 1st of September, 479, or about the beginning of the seventh Babylonian and Persian month in his seventh regnal year” (“Esther and History”). This long absence precisely parallels the gap evident in the book of Esther. But there is more: Recall that the events with the king and Esther pick up in “month Tebeth.” This coincides with December-January of 479–478 b.c.e.—fitting even more tidily with the account in Esther. “Xerxes returned to Persia from his Greek debacle in the fall,” continued Shea. “[T]hus it is natural that he went to his winter residence in Susa, as Herodotus indicates,” where he would have encountered Esther shortly after his return.

Is this incredibly precise fit for the resumption of the story merely coincidence? Or does the timeline fit because it reflects historical reality?

Xerxes’s Monogamy

It was at this time that Esther “obtained grace and favour in his sight more than all the virgins; so that he set the royal crown upon her head, and made her queen instead of Vashti” (Esther 2:17). Esther became not one of a number of queens, but the sole specific replacement for a single queen who had been defrocked years earlier. To this end is another remarkable synchronism: King Xerxes i’s monogamy!

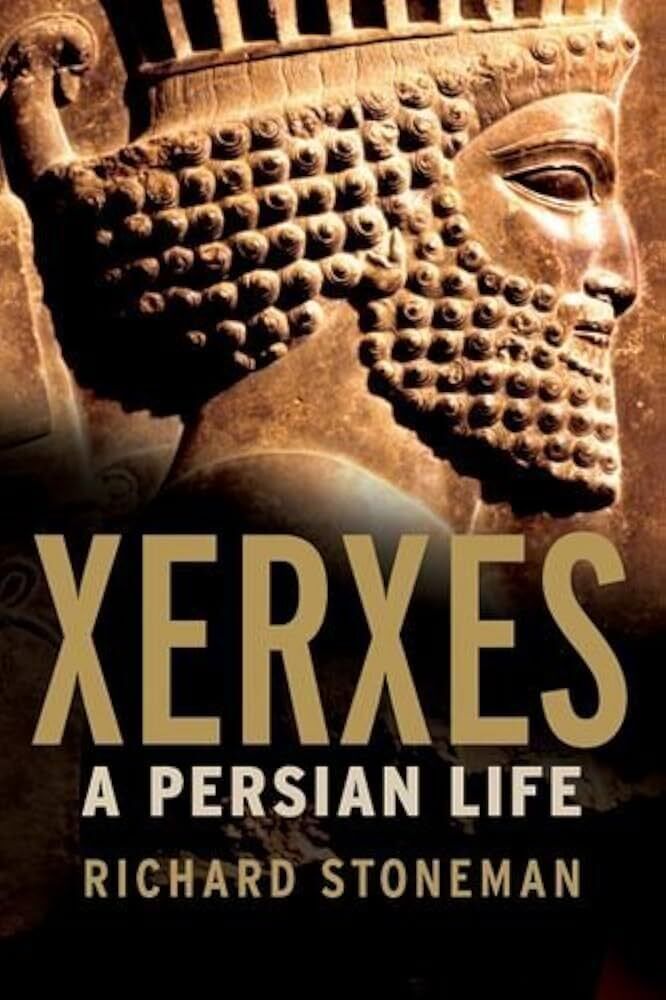

“Regarding Xerxes’s marriage, the first point of agreement between the book of Esther and Greek historians is that this king was always monogamous,” continued Gertoux. Herodotus “only mentions one queen … who was the sole wife of Xerxes.” His father Darius, by contrast, had six wives; Xerxes’s son Artaxerxes also had many wives. “Unlike his polygamous father, Xerxes spent his life married to a single woman …. Xerxes scores quite highly in terms of love and fidelity,” summarizes Dr. Richard Stoneman in Xerxes: A Persian Life.

Against the polygamous backdrop of ancient Persia (and ancient history generally), Xerxes’s marriage to one wife stands out. And it is another uncanny match for the marital monogamy of the biblical Ahasuerus.

The issue is, we know the name of Xerxes’s sole queen: Amestris.

What, Then, of Esther?

Again, from the nabre’s introduction to Esther: “[F]urther investigation shows this is not meant to be a historical account. There is no record of Xerxes having any other queen than Amestris ….”

Some, attempting to harmonize Xerxes’s life with the Esther account, have sought various means of reconciliation—perhaps Amestris was queen between Vashti and Esther? Or perhaps she was queen after Esther? Dr. Shea, in his aforementioned article, posited that Amestris may have been one and the same as Vashti. At face value, this may seem at first to satisfactorily gel with the ancient Greek accounts about her, which make her out to be an evil character—a veritable wicked witch who Herodotus reports was responsible for sacrificing 14 noble children (Histories 7.114).

But attempts to identify Amestris with Vashti, or on either end of Ahasuerus’s marriage to Esther, have largely fallen short. As Carey Moore points out in his 1971 Anchor Bible commentary Esther: “[A]ccording to [Esther] 2:16 and 3:7, Esther was queen between the seventh and 12th years of Xerxes’s reign, but according to Herodotus, Amestris was queen then ….” The various Greek accounts imply that Amestris was queen throughout this period, wielding significant power right through to the end of Xerxes’s reign and on into that of her son and successor, Artaxerxes i (compare this with an intriguing passage in the book of Nehemiah).

There is no room, then, for Esther—not unless Esther is one and the same as Amestris herself. This is the conclusion reached by a handful of researchers, including Gertoux, Dr. Robert Gordis, Prof. Robert Hubbard Jr. and Dr. Mitchell First.

Immediately striking are the core similarities in name—Amestris bearing the same phonetic estr element. As First wrote in his Torah.com article “If Achashverosh Is Xerxes, Is Esther His Wife Amestris?”, a “stronger connection exists between the Greek Amestris and the Hebrew Esther.

The ‘is’ at the end [of Amestris] is just a Greek suffix added to turn the foreign name into proper Greek grammatical form …. The name Amestris is based around the consonants M, S, T and R, and the name as recorded in the Megillah [the book of Esther] is based around the consonants S, T and R. Very likely, this is not coincidence. Perhaps her Persian name was composed of the consonants M, S, T and R, and the M was not preserved in the Hebrew.

Gordis agrees, positing that “‘Esther’ represented an apocopated form of the name ‘Amestris.’ The tendency to shorten foreign names, particularly when their etymology is not known, is widespread” (“Religion, Wisdom and History in the Book of Esther: A New Solution to an Ancient Crux”). He gave the example of the Greek name “Alexander,” widely adopted in foreign sources as “Sander.” Gertoux, for his part, noted that “[t]he name Esther (Stara in Old Persian) means ‘star’” and linked it to the name “the star woman (ama-stara).”

Still, certain difficulties have been raised with the identification of Amestris as Esther. One objection is that Herodotus appears to name Amestris’s father as the military commander Otanes, whereas the biblical Esther’s father is named as Abihail. Still, while “[t]hese names cannot be connected phonologically, it is striking that the name Avichayil [Hebrew pronunciation of Abihail] contains the element ‘ח-י-ל’ which has a military connotation and means ‘strength’ or ‘soldier,’” wrote First. Alternatively, Prof. Robert Hubbard Jr. argues that Herodotus’s reference to Otanes as father of Amestris in Histories 7.61 has been misinterpreted entirely, and that based upon the grammar of the sentence in question, it does not refer to the father of Queen Amestris at all—thus, there is no issue in equating Amestris with Esther based on parentage (“Vashti, Amestris and Esther 1,9”).

Another point of contention is the notion that Amestris was already married to, and together with, Xerxes in Sardis in 480 b.c.e.—chronologically before the marriage to Esther. This has therefore spurred some to try to associate her with Vashti, in some kind of continuing marital relationship with Xerxes at this time. Professor Hubbard tackled this question in his abovementioned article, demonstrating that the limited information about Amestris in Herodotus’s Histories “provides no evidence that Amestris accompanied Xerxes at Sardis during his Greek campaign”—if anything, just the opposite. He concludes that a thorough reassessment of the sources, while “undermin[ing] the theses of Wright and Shea (i.e. that Amestris is Vashti) … leave[s] open the chronological possibility that Amestris and Esther might be the same person since they would be at least chronologically contemporary” (emphasis his).

But what of Amestris’s cruel reputation? Could there be a more mismatched character to that of Esther?

Medusa? Or Misunderstood?

It bears emphasizing here that part of the reason for the difficulty in understanding Persian history during this period is because it comes to us primarily through the Greeks—sworn enemies of the Persians. (For an exaggerated case in point of the caricaturing of Persia and Xerxes i himself, look no further than Zack Snyder’s 300.) Scholars naturally view the Greek accounts of Persia with some suspicion, due to this inherent, and sometimes obviously flamboyant, bias. “Clearly, Herodotus and Ctesias depict Amestris as cruel. It should be noted, however, that many scholars today doubt the stories told by the Greek historians about their enemies the Persians; those concerning royal Persian women are particularly suspect,” First wrote.

Still, even among the negative Greek accounts, there are certain buried nods to the wisdom and discernment of Amestris. Ctesias observed her “great fondness for the society of men” (Persica); Plato, in the fourth century, described large tracts of Persian land named by its inhabitants after her, such as “The Queen’s Girdle” and “The Queen’s Veil” (First Alcibiades). Gertoux highlighted some of these references to “queen Amestris as an influential and wise woman,” in contrast to certain Greek absurdities “concerning Amestris that are obviously false.” Still, he noted that Herodotus’s account “obviously comes from an Achaemenid informant …. We can conclude that the Achaemenid informant did not like Amestris and consequently had portrayed her in a very negative way.”

Is it likely that an Achaemenid would have reason to view Esther negatively? The answer from the biblical text can only be a resounding yes.

Take Herodotus’s claim in Histories 7.114: “It is a Persian custom to bury people alive; for I have heard that Amestris, wife of Xerxes … caused 14 children of the best families in Persia to be buried alive, to show her gratitude to [a certain foreign] god.” The slander of this passage is palpable—and this notion of human sacrifice occurring in Persia is roundly rejected by scholars. But what of the deaths of children of nobility?

Recall the biblical account of the death of Haman and the king’s decree that the Jews in the land be allowed to defend themselves. The Jews in Shushan killed “ten sons of Haman the son of Hammedatha, the Jews’ enemy” (Esther 9:10), hanging them on Haman’s gallows before burying them. Could the memory of such an event have been preserved in some manner through this account of Herodotus? And could such a vengeful Achaemenid informant have been responsible for shaping this almost comically obtuse, evil caricature of Esther/Amestris among the Greeks?

As for the actual account of the near genocide of the Jews, perhaps unsurprisingly, we have no Persian record of it. In fact, we have comparatively little detail of events in general during the latter part of Xerxes’s reign. Despite this, Gordis noted that “the incident is not as improbable as has been thought.

In 88 b.c.e. … Mithradates vi of Pontus ordered a general slaughter of ‘all who were of Italic race,’ men, women and children of every age …. [T]he massacre was to be carried out at the same time everywhere, namely on the 30th day after the date of the royal order. It is reported that 80,000 were killed on that day. That Persian influence predominated in Pontus is well known. Is it possible that Mithradates was maintaining an older Iranian ‘tradition’ for disposing of one’s enemies?”

Gertoux offers another interesting perspective. The “best proof of the existence of this ancient event” relayed in Esther, he notes, “is the total absence of Jewish names in Persian documents before the reign of Xerxes, then the emergence of hundreds of Jewish names just after his reign … proving their full reinstatement in the Persian society.”

All in the Details

The bulk of the content in Esther is dialogue, day-to-day interactions, courtly intrigue and the prevention of an event of historical magnitude. Lacking any archaeological or added textual evidence, these are almost impossible to account for historically. But often, some of the best giveaways for intrinsic historicity are in the smallest of details—the throwaway lines, the details taken for granted. And the book of Esther is replete with them. Here are a few examples:

- The description of the empire, spanning from “India” to “Ethiopia” (Esther 1:1); this geographical reference is paralleled on Xerxes i’s Daiva Inscription.

- Decrees sent out “to every people after their language” (Esther 1:22). The issuing of multilingual decrees, deferring to the personal language of subjects, is a notable feature of Persian rule.

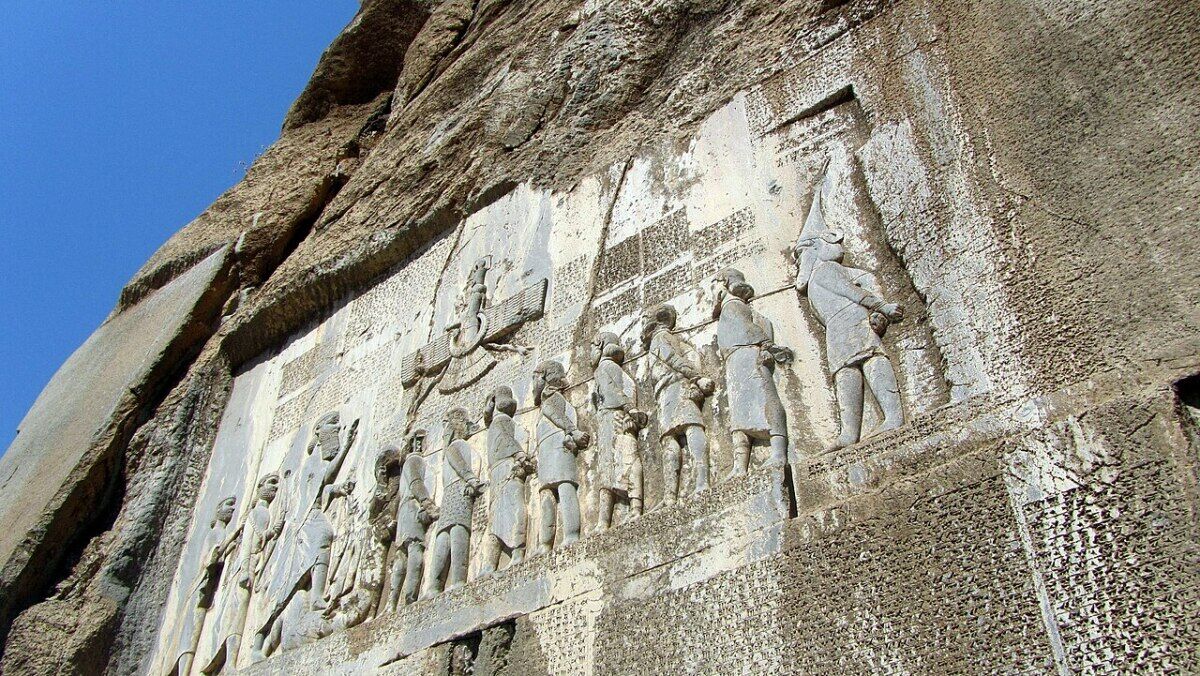

- The book of Esther identifies a cabinet of seven counselors to the Persian king (verses 13-14). Xerxes’s father, Darius the Great, had six such men in his cabinet (per the Behistun Inscription)—pointing to the historicity of an inner circle of roughly the same size.

- Esther 5:1 contains what can only be described as eyewitness detail about the architecture of Xerxes’s palace, with an “inner court of the king’s house, over against the king’s house,” and “royal throne in the royal house, over against the entrance of the house.” This palace layout has been remarkably corroborated, thanks to archaeological excavations of the Susa palace.

- The prominent role of the Persian king’s royal scepter (Esther 5:2): While the exact function of the scepter is still unknown, several Persian palace reliefs depict the Persian king brandishing it.

- The desire of the Persian king to recompense servants for good deeds (Esther 6:1-3)—this is a practice echoed in Darius’s Behistun Inscription. Notable in relation to this are the Persian “lists” made of such benefactors (Esther 2:23), a practice noted by Herodotus (Histories 3.140).

- The kingdom is jointly referred to in numerous verses as that of “Persia and Media” (Esther 1:3, 14, 18; 10:2). This parallels references in inscriptions, such as Darius the Great’s reference to himself as king of “Persia, Media and other countries” (DPg Terrace Inscription).

- There is also the well-known, infamous unchangeability of Persian law, even in cases of judicial error (Esther 8:8).

Alongside these points is the overall raw language of Esther. Skeptics have commonly identified Esther as Classical Greek storytelling—yet as Sarbanani notes, “Although some of this information [in Esther] has resemblance to that provided in Classical [Greek] sources, most of it is in line with evidence directly connected to the Persian Empire. Considering this fact, along with the absence of any Greek word in the text on the one hand and the presence of many Old Persian and Aramaic words on the other hand, it seems that the author of the book of Esther had access to sources directly related to the Persian Empire.”

Craig Davis, in Dating the Old Testament, similarly assesses the language of Esther—its “Classical Biblical Hebrew rather than Late Biblical Hebrew” linguistic features and its total lack of Greek words, as well as its “thoroughly Persian” nature and use of language—concluding that the “most likely date for Esther is around 430 b.c.e., during the governorship of Nehemiah.” He adds that “[t]his would also be consistent with the statement of Josephus that no Old Testament books were written after Artaxerxes,” whose reign ended in 424 b.c.e. Thus, even in the language of the book itself there is consistency, “support[ing] a date deep within the Persian Period.”

In Sum

It’s true that there is a lot we do not yet know about the Esther account, from an outside, historical standpoint. But it is certainly an oversimplification to reject the work as “fictional.”

Does the book contain what could be described as “implausibilities”? Sure. Consider the king’s dream and decision to elevate Mordecai, at the same time as Haman’s plotting his death (Esther 6). But these are not impossibilities and are not demanded by the facts to relegate the book to the status of “fiction.” By the same token, the facts that are present throughout the book—the “throwaway” lines and language slotting tidily into the history of early fifth-century b.c.e. Persia—do clearly attest to its historical nature. Not to mention the book’s conclusion, appealing to readers to cross-reference the information “in the book of the chronicles of the kings of Media and Persia” (Esther 10:2).

Unfortunately, no such Persian chronicles have survived—again, a bulk of what we know about ancient Persia comes from sorely biased Greek sources. Yet ironically, for those who would cast aside Esther as an ahistorical “novella” in favor of the Greek accounts, the very same accusations have been leveled at certain of Herodotus’s descriptions of Xerxes’s Persia, as having “all the literary earmarks of a novella based on oral tradition rather than an eyewitness account” (Hubbard Jr., ibid). It’s a criticism that goes back nearly 2,000 years to the Jewish historian Josephus, who in no uncertain terms condemned Greek historians who, “without having been in the places concerned, or having been near them when the actions were done … put a few things together by hearsay, and insolently abuse the world, and call these writings by the name of Histories” (Against Apion 1.8).

As for the comparative importance of the book in the canon? It is not for this author to decide. Personally, I would not be so bold as to rank it beside the Torah in importance. Yet I would not be so bold as to regard myself an “enemy” of it, to reject the work as “fiction,” or to claim it as “offensive.”

For if anything is evidence of the historicity of Esther and its account of the near-extermination of the Jewish people, it is the regularity with which the same anti-Semitic theme has played throughout history. By far the worst example being still in living memory, with 6 million Jews murdered in the Holocaust alone (not to mention numerous other pogroms and atrocities of the past century). Yet paradoxically, out of those ashes, within mere decades the Jewish nation arose through repeated defensive wars to become more powerful in might than ever before.

One wonders if, 2,500 years from now, future historians will regard the dramatic events of Jewish history during this past century as “farcical,” “hugely ironic,” preposterously “exaggerated”—as “fictional.”

Sidebar: Is This Mordecai?

Mordecai is an intriguing figure in the Esther account, for whom there are a number of peculiarities and points of debate.

One is the nature of his genealogy in Esther 2: “There was a certain Jew in Shushan the castle, whose name was Mordecai the son of Jair the son of Shimei the son of Kish, a Benjamite, who had been carried away from Jerusalem with the captives …” (verses 5-6). Some have argued that for Mordecai to have survived the captivity, he would have been over 100 years old during the reign of Xerxes. To this end, some have argued based on these verses that the mid-sixth century Cyrus should be identified as the Ahasuerus of Esther. The answer is simple, however, if we do not take Mordecai to be the individual carried away captive (which is the sense given in certain translations, such as the King James Version), but rather his great-grandfather Kish.

Another point of confusion is Mordecai’s relationship with Esther, popularly named as her “uncle.” Actually, the “biblical text is straightforward,” wrote Prof. B. Barry Levy. Esther 2:7 reveals that “Esther is the daughter of Mordechai’s uncle, and thus, Esther and Mordechai are first cousins. … No traditional rabbinic text claims that Mordechai was Esther’s uncle, but the idea has both popular currency and support in early texts” (“What Was Esther’s Relationship to Mordechai?”). Levy primarily credits the popular spread of this assumption to Jerome’s Latin Vulgate, “which says that Esther was the daughter of Mordechai’s brother.”

But is there any evidence for the man himself, in the courts of Persia? Prof. David Howard Jr. summarizes the evidence in An Introduction to the Old Testament Historical Books: “[A] tablet discovered in 1904 contained the name ‘Marduka’ as a high Persian official during the early years of Xerxes’s reign, which corresponds to the time of Mordecai. In more recent years, more than 30 texts have been uncovered with the name Marduka (or Marduku), referring to up to four different individuals, one of whom could easily have been the biblical Mordecai.”