When it comes to examining the history of the Persian Empire through the lens of the Bible, some of the books that come most readily to mind are Ezra, Nehemiah and Esther. These books record events, personalities and details that occurred over a 100-year span—from Cyrus the Great’s takeover of Babylon (539 b.c.e.) to Darius ii’s reign (424–404 b.c.e.).

Some of the Bible’s most vivid and remarkable stories are recorded in these three books. In the book of Ezra, Cyrus the Great issues his monumental decree to release the Jewish people from captivity so they can return to Jerusalem to rebuild the temple and restore proper worship. In the book of Esther, a young Jewish girl rises to the ranks of queen of the Persian Empire and is used to save the Jewish race from extinction. In Nehemiah, one man’s leadership rallies the Jewish people to rebuild the walls of Jerusalem—with a sword in one hand and a spade in the other.

These stories are remarkable, inspiring and miraculous. But what about proving the accuracy of these stories? Can the scientific and archaeological evidence from the Persian Empire be reconciled with the biblical account?

Over the past 200 years, archaeology has produced some wonderful finds that align with the history recorded in the Bible. It is important to note: Archaeological excavations related to the Persian Empire have produced a wealth of artifacts. Each Persian king mentioned in the Bible—Cyrus the Great, Darius the Great, Xerxes and Artaxerxes i—has been attested to archaeologically, and each has his own corpus of inscriptions and archaeological evidence that align with the dating you would expect from the biblical text.

This article is merely intended to highlight artifacts and history of the Persian Empire as they pertain to the greatest historical record we have—the Bible.

The Nonexistent King

The Bible states that the final king to rule over the Babylonian Empire was Belshazzar. Daniel 5 vividly describes Belshazzar’s final night: a raucous occasion of celebration and debauchery.

Although the Bible is clear on the events before Babylon’s fall, prior to 150 years ago, it stood alone in describing a personality named Belshazzar. The accepted belief was that he didn’t exist. Instead, Nabonidus was widely regarded as the final king of Babylon. Rather than being killed when Cyrus invaded, he was taken captive. It appeared that the Bible was at loggerheads with what the scholars accepted as “historical fact.”

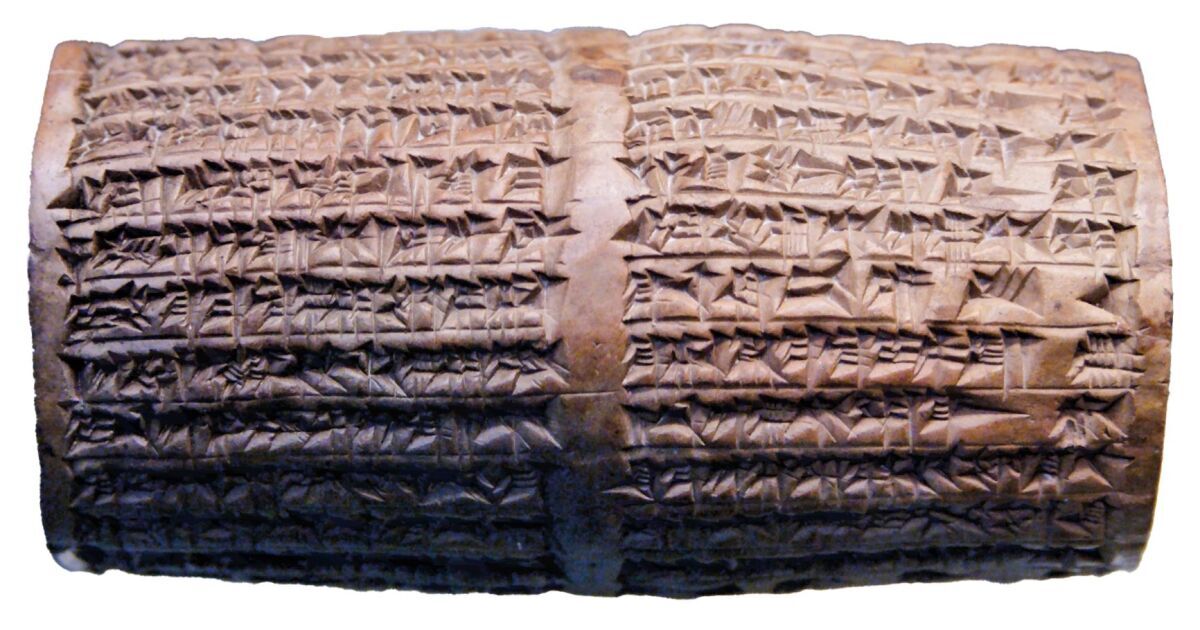

That all changed in 1854 when British Consul John Taylor discovered four 4-inch-long by 2-inch-wide cylinders in a ziggurat in the area of ancient Ur. Each cylinder bears the same inscription: a description of Nabonidus’s restoration work at the temple and a prayer for his eldest son, Belshazzar.

The last paragraph of the inscription reads: “As for me, Nabonidus, king of Babylon, save me from sinning against your great godhead and grant me as a present a life long of days, and as for Belshazzar, the eldest son—my offspring—instill reverence for your great godhead in his heart and may he not commit any cultic mistake, may he be sated with a life of plenitude.”

In his official letter announcing the discovery, Sir Henry Rawlinson, “the father of Assyriology,” wrote: “I hasten to communicate … a discovery … which is of the utmost importance for scriptural illustration. … The most important fact, however, which [the Nabonidus Cylinders] disclose, is that the eldest son of Nabonidus was named Bel-shar-ezar, and that he was admitted by his father to share in the government. This name is undoubtedly the Belshazzar of Daniel and thus furnishes us with a key to the explanation of that great historical problem which has hitherto defied solution” (emphasis added).

With the discovery of these four cylinders, it was clear that Belshazzar was made joint king over Babylon while his father was on campaigns in Arabia. Another Babylonian chronicle, the “Verse Account of Nabonidus,” also makes this clear, stating that before taking his long journey into Arabia, Nabonidus “entrusted the army to his oldest son …. He let everything go, entrusted the kingship to him.”

As second-in-command, it is also clear why Belshazzar made Daniel “the third ruler in the kingdom” (Daniel 5:29); it was the next highest office he could give.

The Nabonidus Cylinders are a key to aligning the scientific and biblical evidence of the Persian Empire—from the very foundation: the Persian army’s capture of Babylon.

A Miraculous Decree

After conquering Babylon in 539 b.c.e., Cyrus the Great cemented himself as emperor over an extensive empire. But it wasn’t just the expanse of his empire or his own military prowess that made Cyrus great; rather Cyrus is most well known for his humane and beneficent treatment of his subjects. He showed tolerance for the conquered peoples’ government, traditions and religion. This was in complete contrast to the preceding empires’ harsh and violent treatment of those they conquered.

Historian Will Durant writes in Our Oriental Heritage, “[H]e was the most amiable of conquerors and founded his empire upon generosity.” This is most profoundly evidenced by the Cyrus Cylinder—a clay cylinder (discovered in 1879) inscribed with Akkadian cuneiform script recording Cyrus’s conquest of Babylon and his initiative to allow captives to return home and resume their religious practices.

This artifact parallels the remarkable history recorded in 2 Chronicles 36:22-23 and Ezra 1:1-4. Notice Cyrus’s decree after conquering Babylon: “Thus saith Cyrus king of Persia: All the kingdoms of the earth hath the Lord, the God of heaven, given me; and He hath charged me to build Him a house in Jerusalem, which is in Judah. Whosoever there is among you of all His people the Lord his God be with him—let him go up” (2 Chronicles 36:23).

While the Cyrus Cylinder is specifically about resettling Babylonian exiles, it proves that returning displaced peoples was a hallmark of Cyrus’s reign. When combined with the biblical text, we know that Cyrus “made a proclamation … and put it also in writing” that the Jewish captives were to be given independence to return to and rebuild Jerusalem and practice their religion—just as the archaeological evidence shows Cyrus did with other captive peoples.

The first-century Jewish historian Josephus recorded in Antiquities of the Jews that after telling “the most eminent Jews” in Babylon that their people could return, he wrote a letter to the governors in the area of Judea, stating: “I have given leave to as many of the Jews that dwell in my country as please, to return to their own country, and to rebuild their city, and to build the temple of God at Jerusalem, on the same place where it was before” (11.1.3). According to the book of Ezra, 42,360 Jews departed from Babylon for Jerusalem (Ezra 2:64).

‘Across the River’

Around 15 years after Cyrus’s decree, Darius i, known as Darius the Great, came to power. He was known for his brilliant administrative ability. Under his leadership, the Persian Empire spanned over 2 million square miles. To manage such a vast empire, Darius followed Cyrus’s example and established 20 “satrapies,” or provinces. Each province was led by a governor who directly answered to the emperor.

The Bible describes one such Persian official named “Tattenai, the governor beyond the River” (Ezra 5:3; 6:6, 13). He sent a letter to Darius, questioning whether the Jews should be permitted to continue rebuilding the temple.

Tattenai, with his unique title, has been corroborated in the archaeological record.

A cuneiform tablet written in 502 b.c.e., the 20th year of Darius’s reign, records a financial transaction. In addition to the details of the fiscal agreement, the document lists an individual who was present to witness the transaction: a servant of “Tattenai, Governor of Across-the-River.” “Across the river” refers specifically to a province west of the Euphrates River and matches the title given to Tattenai in the Bible: “governor beyond the River.”

Even a seemingly obscure Persian individual is accurately recorded—to the very title—in the biblical text.

Palace Fit for a Queen

During his reign, Darius the Great made Shushan (modern-day Susa) his administrative capital. There he built a magnificent palace. Darius’s son, Xerxes i (486–465 b.c.e.), continued to use this palace during his reign.

The events of the book of Esther revolve around this palace and provide a detailed description in the first chapter: “[T]he king made a feast unto all the people that were present in Shushan the castle, both great and small, seven days, in the court of the garden of the king’s palace; there were hangings of white, fine cotton, and blue, bordered with cords of fine linen and purple, upon silver rods and pillars of marble; the couches were of gold and silver, upon a pavement of green, and white, and shell, and onyx marble” (Esther 1:5-6).

King Darius recorded his own description of the palace. On what is known as the “Foundation Charter,” he wrote: “The palace which I built at Susa, from afar its ornamentation was brought. … The cedar timber, this was brought from a mountain named Lebanon. … The gold was brought from Lydia and Bactria …. The precious stone lapis-lazuli and carnelian which was wrought here, this was brought from Sogdiana. The precious stone turquoise, this was brought from Chorasmia …. The silver and the ebony were brought from Egypt. The ornamentation with which the wall was adorned, that from Ionia was brought. The ivory … was brought from Ethiopia and from Sind and from Arachosia. The stone columns which were wrought, a village by name Abiradu in Elam, from there were brought. … Saith Darius the King: At Susa a very excellent work was ordered, a very excellent work was brought to completion.”

Beyond the parallels in the description of materials used for the palace, the book of Esther also describes specific rooms in the palace complex that can be corroborated with the archaeological site.

In Ancient Persia and the Book of Esther, Prof. Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones writes, “[E]xcavators of the Susa site have often enthused over the correlations to be found between the literary evidence of Esther and what the archaeology unearthed.” Those who most closely deal with the scientific evidence of Susa recognize the parallels between the archaeology and biblical account. Various researchers have noted that the Bible accurately describes the architectural layout of the palace. Take note of some of the specific palace rooms listed in the biblical account.

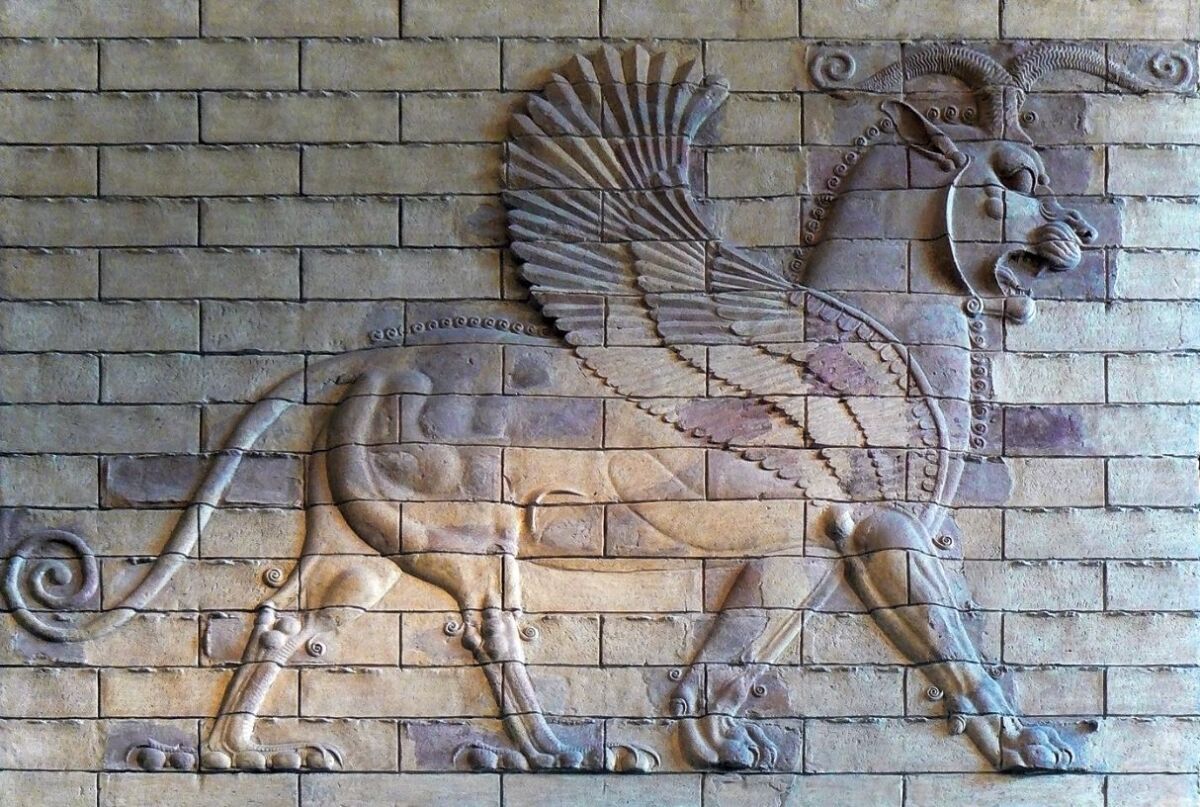

The first room the Bible describes is “the court of the garden,” where Xerxes hosted his feast (Esther 1:5). This court parallels the 11,000-square-meter (120,000-square-foot) banquet hall in Susa that boasted 36 pillars, each with an impressive 4-meter-tall (13 feet) capital. The walls of this banquet hall were lined with ornate lion and archer friezes. Perhaps the “blue” stone that Esther 1 refers to are these blue-hued friezes.

Chapter 5 describes Esther standing in “the inner court … over against the king’s house” (verse 1). An inner courtyard has been discovered, sitting directly across from what would be Xerxes’s throne room and apartments. Historian Jona Lendering wrote that this courtyard is “probably identical to the inner court mentioned in the biblical book of Esther. It gives access to King’s Hall, where the king received his guests …” (“Susa, Palace of Darius the Great,”).

A larger courtyard sits just inside the eastern entrance of the palace. This courtyard parallels the outer court described in Esther 6:4: “… Now Haman was come into the outer court of the king’s house, to speak unto the king ….”

One final location detailed throughout the biblical text is “the king’s gate.” The Bible makes 10 references to Mordecai, Esther’s close relative, sitting in or being near the king’s gate. Prior to 1970, however, there was no evidence of a palace gate at Susa. That all changed after French archaeologist Jean Perrot’s 1970–1978 excavations. Perrot’s team uncovered a truly monumental gatehouse structure on the eastern side of the palace.

In The Palace of Susa, Perrot wrote that early excavators’ identification of this palace as the one from the book of Esther “was always vague. The gate had not been discovered, and the plan and the general scheme of the palace were not understood …. Today, we have better reasons for thinking that Darius’s palace at Susa, begun in 520 b.c.e., completed by Xerxes … is indeed the palace in the mind of the author of the book of Esther ….”

During his excavations, he said: “Today we reread with renewed interest the book of Esther, whose detailed description of the interior layout of the palace of Xerxes is now in good agreement with archaeological reality” (Historique des Recherches; Let the Stones Speak translation).

Defending the Defenses

Another Jewish individual the Bible describes as being in the palace at Shushan is Nehemiah.

Just under 100 years after the Jews were released from captivity, Jerusalem’s walls hadn’t been rebuilt. The city sat defenseless as enemies of the Jews’ effort relentlessly worked to stifle progress.

Nehemiah, a cupbearer in the royal court of Artaxerxes i (son of Xerxes), was eager to help his people in Jerusalem. Around 444 b.c.e., Artaxerxes gave Nehemiah permission to go to Jerusalem as a governor and join the rebuilding efforts.

Upon arriving in Jerusalem, Nehemiah surveyed the situation, specifically taking note of the walls (Nehemiah 2:13). He then told the people: “[C]ome and let us build up the wall of Jerusalem …” (verse 17). This monumental effort of rebuilding Jerusalem’s walls has been attested to in archaeology.

During her 2007 excavations in the City of David, Dr. Eilat Mazar intended to repair a tower that she believed dated to the Hasmonean dynasty (142–37 b.c.e.). However, after six weeks of excavation, Dr. Mazar concluded that the tower wasn’t Hasmonean but rather Persian; she dated its construction to around 450 b.c.e.

“Under the tower,” Dr. Mazar said in a Nov. 8, 2007, conference, “we found the bones of two large dogs—and under those bones a rich assemblage of pottery and finds from the Persian Period [sixth to fifth centuries b.c.e.]. No later finds from that period were found under the tower.” “Dog burials” are a known hallmark of the Persian Period, which along with the pottery, made clear to Dr. Mazar that this structure was built during Nehemiah’s projects in Jerusalem.

Dr. Mazar also discovered a wall that was connected to the tower and likely dated to the same period. It was evident that this wall was constructed in a hasty manner. Hurried construction is exactly what you would expect from a wall that was built in just 52 days (Nehemiah 6:15).

“Finally, the absence of certain material helped Dr. Mazar date the tower and associated wall,” we wrote in “Discovered: Nehemiah’s Wall.” “Yehud seal impressions are very common during Persian Period Judah. Yehud was what Judah was called during Persian rule. During Yigal Shiloh’s excavations in the City of David in the 1980s, many Yehud bullae had been found, all of which dated to the second half of the fifth century b.c.e. or later. But here, in this almost 5-foot-thick Persian layer beneath the Northern Tower, Dr. Mazar didn’t find a single one. That meant this material must have been in place before the middle of the fifth century b.c.e.”

Dr. Mazar’s excavations proved that right at the time we’d expect Nehemiah to be building up Jerusalem’s defenses, a hastily constructed wall and tower were erected—giving archaeological evidence of the book of Nehemiah.

A Priest and an Adversary

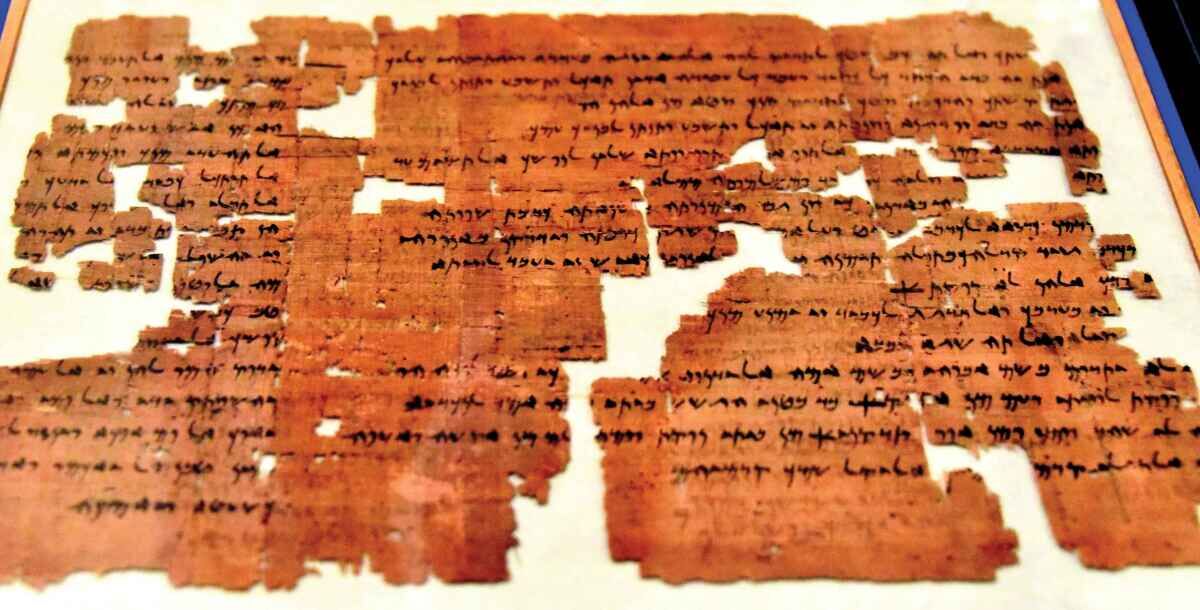

Another clue for the veracity of the book of Nehemiah comes from a papyrus letter dated to around 407 b.c.e. This Aramaic-language document, known as the Elephantine Temple Papyrus, lists two biblical figures from the time of Nehemiah: Johanan the high priest and Sanballat, adversary of Nehemiah’s work.

Elephantine is an island located in the Upper Egypt portion of the Nile River. Beginning around 650 b.c.e., a Jewish community developed in Elephantine. While the exact origins of this community are unclear, Prof. Bezalel Porten wrote in Biblical Archaeology Review: “The Jewish community at Elephantine was probably founded as a military installation in about 650 b.c.e. during Manasseh’s reign. A fair implication from the historical documents, including the Bible, is that Manasseh sent a contingent of Jewish soldiers to assist Pharaoh Psammetichus i (664–610 b.c.e.) in his Nubian campaign and to join Psammetichus in throwing off the yoke of Assyria, then the world superpower. Egypt gained independence, but Manasseh’s revolt [against Assyria] failed; the Jewish soldiers, however, remained in Egypt.”

Excavations of Elephantine have produced 175 papyrus documents that date to the time Egypt was under the control of the Persian Empire, following Cambyses ii’s conquest of Egypt.

The Elephantine Temple Papyrus, or Papyrus No. 30, records a letter sent to a Persian official named Bagohi, the governor of Judah who most likely took over the position sometime after Nehemiah. The letter discusses the destruction of the Elephantine “temple of yhw,” or yhwh. It reads, “To Bagohi governor of Judah, [from] the priests who are in Elephantine the fortress. … [W]e sent a letter [to] our lord, and to Jehohanan the high priest and his colleagues the priests who are in Jerusalem ….” Jehohanan, a longer version of the name Johanan, is mentioned in the biblical text as a “son of Eliashib the high priest,” who served during the time of Ezra and Nehemiah (Ezra 10:6; Nehemiah 12:22-23).

The letter continues further down: “Moreover, all these things in a letter we sent in our name to Delaiah and Shelemiah, sons of Sanballat, governor of Samaria.” Sanballat the Horonite is mentioned in various scriptures (see Nehemiah 2:10, 19; 3:33; 4:1; 6:1, 2). Sanballat was governor of Samaria when Nehemiah arrived in Jerusalem. He led a campaign to stop Nehemiah’s wall-building project. While his sons aren’t specifically mentioned in the Bible, Delaiah and Shelemiah are very common biblical names—both of which are mentioned in the book of Nehemiah (Nehemiah 3:30; 6:10; 7:62; 13:13).

There is a second possible mention of Sanballat in archaeology. A fragmented bulla from Wadi Daliyeh reads: “…iah, son of […]ballat, governor of Samar[ia].” This bulla dates to the reign of Artaxerxes iii, nearly 100 years after the Sanballat of Nehemiah’s day, so it could refer to a different individual, perhaps a later relative. However, the legible suffix of the first listed name would align with either of Sanballat’s sons: Delaiah or Shelemiah. Regardless of the exact identity of the Sanballat listed on the Wadi Daliyeh bulla, it is proof that the name Sanballat—a key antagonist of the Bible—was in use during this general time frame in Samaria.

The King of Qedar

Sanballat is not the only enemy of Nehemiah listed in the Bible. “[W]hen Sanballat the Horonite, and Tobiah the servant, the Ammonite, and Geshem the Arabian, heard it, they laughed us to scorn, and despised us …” (Nehemiah 2:19). Geshem the Arabian worked alongside Sanballat in opposing the Jews. He was a prominent figure in this region, who likely had close connections to officials in Persia.

“Geshem was in fact the paramount Arab chief in control of the land-routes from Western Asia into Egypt,” writes Kenneth A. Kitchen. “The Persian kings had always maintained good relations with the Arab rulers of this region ever since Cambyses had enlisted their aid for his invasion of Egypt in 525 b.c.e.—so Geshem’s word could well have endangered Nehemiah at the Persian court” (Ancient Orient and Old Testament). What evidence do we have of this “paramount Arab chief”?

Evidence of Geshem has been discovered on an inscription from 410 b.c.e.

In 1947, archaeologists excavating Tell-Maskhuta in Upper Egypt discovered a collection of silver bowls used in the dedication to an Arabian goddess. Each bowl bears an inscription. The most notable of which reads: “That which Qaynu, son of Gashmu, king of Qedar, brought in offering ….” “Gashmu” is another spelling of the name Geshem; both spellings are used in the book of Nehemiah (see Nehemiah 6:6; King James Version). Qedar was a kingdom in northwest Arabia, which fits well with Geshem’s biblical title: “the Arabian.”

William J. Dumbrell wrote for the Bulletin of American Schools of Oriental Research that when taken together, all the different pieces of information “confirm that Qaynu bar [son of] Gashmu was the son of the adversary of Nehemiah” (October 1971). Once again, the Bible proves its reputation as an authoritative and accurate historical source.

Harmonizing the History

A study of Persian history shows that when critics say a biblical king doesn’t exist, in the end, the Bible is proved right and the critics are proved wrong. When the critics say a biblical book is fable or legend, the archaeology proves the Bible is filled with factual, historical details—down to the very architectural layout of a building.

Harmonizing the history of the Persian Empire with the biblical text is a fascinating and inspiring exercise that shows just how necessary biblical archaeology is. The Bible fills in the gaps of the archaeological record and gives us a more complete picture—even for a world power as well documented as the Persian Empire.