One of the most remarkable figures in Jewish history is Hadassah, or Esther—who went from being one of many ordinary displaced Jewish girls to the genocide-preventing queen of Persia.

When it comes to Jerusalem’s history specifically, one of the most remarkable figures is Nehemiah—known for his unwavering grit, shrewdness and efficiency during one of the city’s most vulnerable periods. His swift wall-building was emblematic of other forms of security he brought to the Jewish capital at the time. His chronicle of events provides some of the most specific historical details about the city ever recorded.

Using the biblical record as a chronological guide, Esther’s and Nehemiah’s lives in Persia would have overlapped. Nehemiah’s account begins about 20 years after the death of Xerxes i, Esther’s husband (read “The Book of Esther: Fact or Fiction?”).

But is there even more in the biblical account that connects these two heroic personalities? The exchange between Nehemiah and Artaxerxes may divulge an answer.

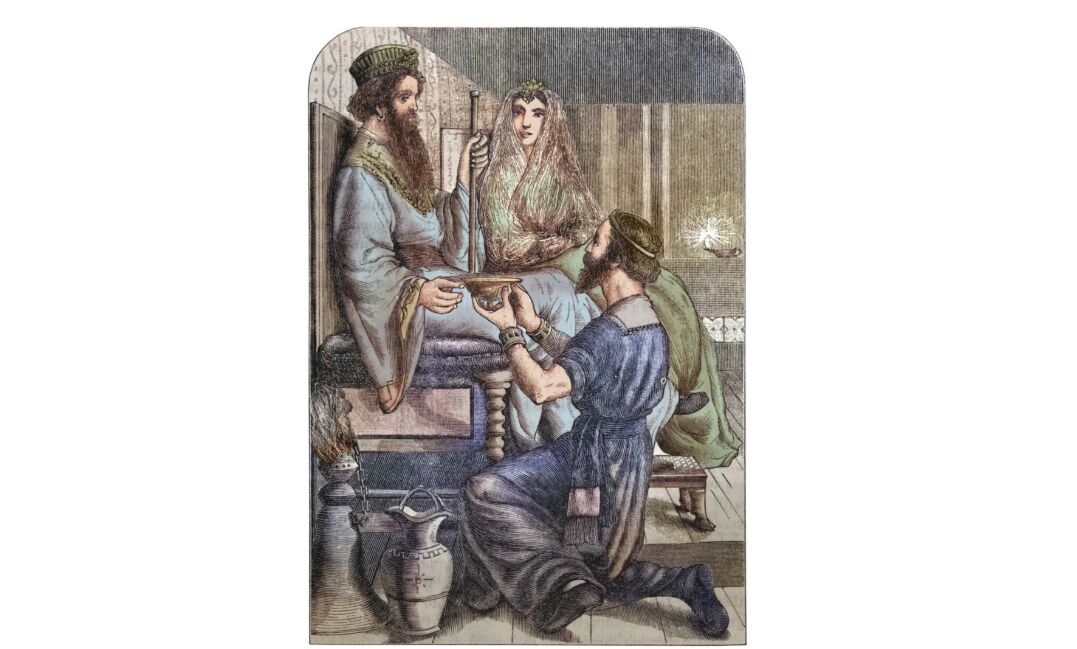

‘The Queen Also Sitting by Him’

Nehemiah 2 contains an incredible exchange between Artaxerxes—son and successor of Xerxes i—and his cupbearer Nehemiah. The king noticed an overt air of sadness about his servant, which made Nehemiah “sore afraid” (verse 2). Other biblical accounts indicate that someone in deep mourning would have stayed away from the Persian royal court (see Esther 4:1-2), so he may have felt in danger of a grievous violation here.

Nehemiah defended his disposition by describing the plight of Jerusalem, mentioning the charred gates and twice the importance of its tombs (Nehemiah 2:3-5). The king responds in verse 6 with a couple of follow-up questions, and then the account implies Artaxerxes was happy to send Nehemiah away for a set time.

Another intriguing detail is nestled in verse 6: “And the king said unto me, the queen also sitting by him: ‘For how long shall thy journey be? and when wilt thou return?’ So it pleased the king to send me; and I set him a time.”

Notice that Nehemiah’s account is written in the first person. As with any autobiographical account, the details he chooses to include or exclude speak volumes of what is significant to him. Why does Nehemiah mention the presence of this queen right before the king’s response and subsequent permission to return to Judah?

The Bible’s Queens

As the wife of Xerxes, Esther would be the “queen mother” at this time. Artaxerxes’s wife, or queen “consort,” was a woman named Damaspia (he had other wives and concubines, but she was the mother of his heir).

The handful of Hebrew words for “queen” don’t really make a distinction in these roles—whether a ruling female monarch (e.g. queen of Sheba), a wife of a monarch (a consort) or the mother of a ruling king. It’s worth briefly exploring how the Bible uses these terms to shed more light on what is being said (or not said) in Nehemiah 2:6.

The Hebrew Bible describes about a dozen queens, if you don’t count the 60 anonymous ones in Song of Songs 6:8-9. Malkhah is most common word for queen; simply and logically, it is the feminine form of the word for “king” (melekh). This Hebrew word (and the nearly identical Aramaic equivalent) describes the queen of Sheba, Persia’s Vashti, the queen in Belshazzar’s reign, and half of these references are to Esther herself. (A similar word describes the object of pagan worship, the “queen of heaven”—a feminine noun from the root meaning to reign, and perhaps simply a feminine form of the pagan Molech.)

Another word describes a woman of kingly relation: g’virah. This is the feminine form of the word gavar (ruler or lord—close to the modern Hebrew for “man”). This shows the versatility of any word for “queen.” For instance, it can refer to a wife of a pharaoh (1 Kings 11:19). In contrast, Jeconiah’s “queen-mother” is listed as being part of a wave of Babylonian captives (Jeremiah 29:2); other accounts mention his “mother” (singular) and his “wives” (plural)—not plural queens (see 2 Kings 24:12, 15). Even King Asa’s grandmother is explicitly referred to as “queen” (1 Kings 15:13; 2 Chronicles 15:16), who at one time would have been “consort.”

The same versatility is built into the English language: Elizabeth ii, her mother and her paternal grandmother were all referred to as “queen” when all three were alive.

Who Is This Seated ‘Queen’?

The remarkable thing about Nehemiah 2:6 is the word for queen is completely unique, with the exception of one anonymous reference in Psalm 45:10. The word shaygal appears to come from a root implying sexual intimacy—which would not be the case between Artaxerxes and Esther, but definitely between Artaxerxes’s father and Esther, since they are his parents.

Psalm 45:10 (verse 9 in other translations) describes an unnamed king with a queen (shaygal) standing next to him.

In Nehemiah 2:6, we see a woman sitting beside Artaxerxes, but she is not functioning as “queen” in the sense that would require the feminine form of “king” or the feminine form of “ruler.” There is a family connection here. And for it to be Esther—who claims half the biblical references to a queen, though a different word when her husband is the actual king—is quite likely.

The use of shaygal causes some commentators, like Adam Clarke, to believe this woman to be some sort of concubine. But that makes Nehemiah mentioning her in his autobiographical prose all the stranger.

The Jamieson, Fausset and Brown Commentary notes: “As the Persian monarchs did not admit their wives to be present at their state festivals, this must have been a private occasion.” We could add that concubines would also be excluded from this kind of affair. It continues:

The queen referred to was probably Esther, whose presence would tend greatly to embolden Nehemiah in stating his request; and through her influence, powerfully exerted it may be supposed, also by her sympathy with the patriotic design, his petition was granted, to go as deputy governor of Judea, accompanied by a military guard, and invested with full powers to obtain materials for the building in Jerusalem, as well as to get all requisite aid in promoting his enterprise.

Let the Stones Speak editor in chief Gerald Flurry commented on Nehemiah 2:6 in his booklet on Ezra and Nehemiah: “The king (and queen) granted all of Nehemiah’s requests. Why did they do so? Nehemiah recognized that it was God who had given him great favor. Even though the king and queen physically supported him, their support was directly inspired by God.”

This divine support resonates more poignantly if it is Esther herself seated next to Persia’s king.

A Queen for Jerusalem

Consider the details covered: Based on the Hebrew word chosen, she is not in the same position of authority as Esther is when Xerxes is ruling. But Esther is presumably still alive at this moment, still functioning as the Jewish queen mother of Persia. And, perhaps most convincingly of all, she is significant to Nehemiah. It appears her presence was positive and impactful to the outcome of the story. Perhaps the presence of this Jewish heroine made him more candid with Artaxerxes, knowing that the king’s mother would be sympathetic to his cause.

If so, Esther stands not only as the powerful queen who stood in the way of the Jewish people being blotted out, she also played a part in the renaissance of strength that Jerusalem itself achieved under Nehemiah.