In the pages that follow, you will be presented with a reasonably thorough examination of a wide variety of scientific and historic evidence associated with David, Solomon and the 10th-century b.c.e. kingdom of Israel. This evidence, each a piece of the larger puzzle, comes in the form of several archaeological sites; monumental walls, gatehouses and structures; inscriptions, fragments of pottery, textiles, metals and foodstuffs, among other items.

As we consider these individual pieces and then connect them, we need an illustration of what we are creating. As previously mentioned, our “image on the box” is provided by the biblical text, three books in particular: Samuel, Kings and Chronicles. Compiled between the ninth and fifth centuries b.c.e. using earlier writings from the prophets Samuel, Nathan and Gad, these books give a detailed description of the united monarchy.

They reveal the names of all the major and many of the minor characters; their relationships with one another; the duration of the reigns of Saul, David and Solomon; the nature of Israel’s economy (for example, where it sourced its gold and silver); the identity of Israel’s neighbors, and many of their interactions, skirmishes and wars; Israel’s territorial boundaries, many of the main regions and cities; and even specific projects, such as the construction of cities, walls and buildings. They provide detailed insight into Israelite culture and society, their diet, the style and color of their clothing, their marriage and family life.

It is extraordinary just how much detail is recorded in the historical text—and a good portion of it, as we will see, is confirmed, directly and indirectly, by the archaeological record.

Judges to King Saul

In many ways, the origin of 10th-century b.c.e. Israel is found in the time period of the judges. This was a dark, dangerous and largely hopeless time for Israel. “In those days there was no king in Israel; every man did that which was right in his own eyes” (Judges 21:25).

Lacking a monarch, or any sort of centralized government outside of the tabernacle, the nation was a company of relatively independent tribes. Israel’s vulnerability was made worse by the fact that most of the tribes didn’t get along especially well. The period of the judges lasted roughly 300 to 350 years (from the early 14th to mid-11th century b.c.e.). It was a time of oppression and conflict. Enemies included the Philistines, Canaanites, Zidonians, Hivites, Arameans, Moabites, Midianites and Ammonites.

The situation marginally improved in the mid-11th century, when God granted the wish of the people and instructed the Prophet Samuel to anoint a king. Saul—a tall, muscular and handsome Benjaminite—looked the part.

Saul ruled from Gibeah in the tribal territory of Benjamin. His rule began with promise. He led a united Israelite army to defeat the Ammonite siege of Jabesh-gilead (1 Samuel 11) and was initially victorious against the Philistines. But the headstrong, self-reliant king soon began to stumble. Over time, he became increasingly disobedient and indifferent to the Prophet Samuel’s warnings (1 Samuel 13:13-14). The Philistines, situated on the coastal plain beside the Mediterranean Sea, were Israel’s greatest threat and Saul’s greatest stress.

King Saul’s fate was finally sealed during a battle with the Amalekites, during which he flagrantly rejected the instructions of Samuel the prophet. “And Samuel said unto him, The Lord hath rent the kingdom of Israel from thee this day, and hath given it to a neighbour of thine, that is better than thou” (1 Samuel 15:28). Samuel distanced himself from Saul and mourned the king’s descent into madness.

Enter David

In 1 Samuel 16, God commanded the prophet to travel to the farm of Jesse, a Bethlehemite in the land of Judah, where he was to anoint Israel’s next king. Samuel surveyed Jesse’s impressive sons but was informed by God that Israel’s next king was in the field, tending his father’s sheep. The lad, probably only 12 or 13 years old, was summoned. Surrounded by his surprised family, who had forgotten to invite him to the special occasion, the ruddy David was anointed Israel’s next king.

David then returned to his father’s sheep. For how long, we don’t know. We next read of him being invited to Gibeah, where Saul was depressed and in need of a musician to soothe his troubled mind. A servant suggested David: “Behold, I have seen a son of Jesse the Beth-lehemite, that is skilful in playing, and a mighty man of valour, and a man of war, and prudent in affairs, and a comely person, and the Lord is with him” (verse 18). David began to spend more time at the king’s court.

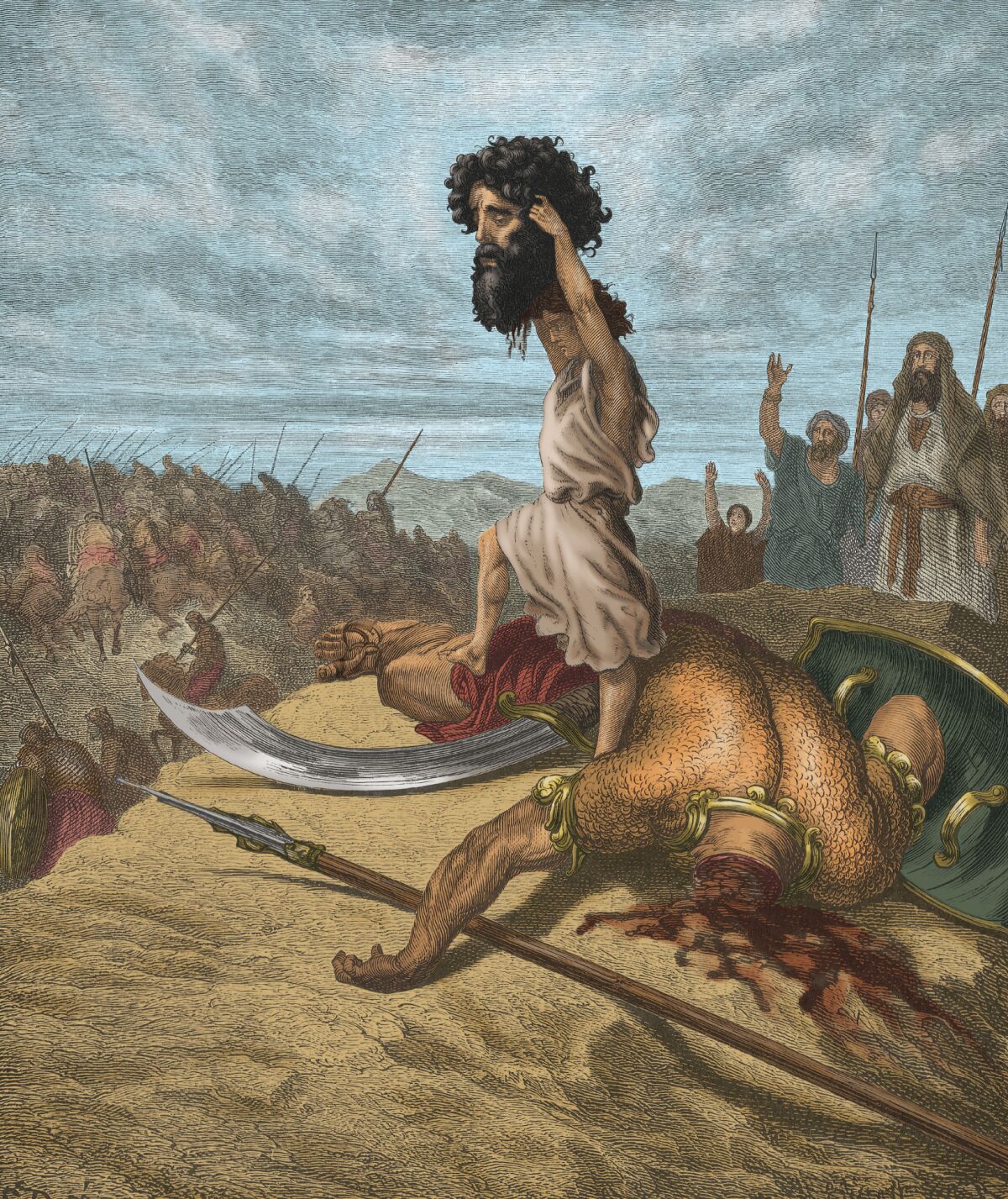

When the Philistines, pursuing eastward expansion, marched into the hill country of Judah, they were met in the Valley of Elah by King Saul and his army. For 40 days, the armies glared at each other across the valley. Israel’s fear was compounded by the presence of Goliath, a Philistine giant who taunted cowardly Saul and his army.

During this standoff, Jesse dispatched his youngest son to the battlefront. When David arrived and was briefed by his brothers, he grew furious. “[W]ho is this uncircumcised Philistine, that he should defy the armies of the living God?” (1 Samuel 17:26; nkjv). King Saul granted the teenager his request to challenge Goliath. David grabbed his slingshot and ran toward the giant. Goliath was in the middle of his rant when he felt a blow to his forehead and warm fluid trickling down his face. Everything turned black, and he crumpled to the ground. His life had come to an end at the hand of a boy. The Philistines panicked and fled.

David’s victory over Goliath catapulted him to national fame. He was invited into King Saul’s inner circle. “And Saul took him that day, and would let him go no more home to his father’s house” (1 Samuel 18:2). But David’s success in the Valley of Elah marked the beginning of a challenging new phase. Across Israel, people praised and adored David more than the king. “Saul hath slain his thousands,” the women and children sang, “and David his ten thousands” (verse 7). King Saul grew jealous: David had to die.

Left with no choice, David fled. David and a growing entourage ended up being fugitives on the run from Israel’s increasingly psychotic king for over a decade. In this trying time, the young man found solace and strength by writing psalms. David and his men migrated around Judah’s mountains and deserts, sleeping in caves, begging for sustenance, engaging in occasional battles. David was always glancing over his shoulder.

David Becomes King

Then came the day that King Saul and three of his sons died on Mount Gilboa in a battle with the Philistines. Saul’s son Ishbosheth was anointed king over Israel at Mahanaim. Meanwhile, in Hebron, one of the six cities of refuge, David became king of Judah. A seven-year civil war ensued. But when Ishbosheth and his commander Abner were assassinated, Judah and Israel reconciled. Around 1003 b.c.e., King David finally became king of the united nation of Israel.

“David was thirty years old when he began to reign, and he reigned forty years. In Hebron he reigned over Judah seven years and six months; and in Jerusalem he reigned thirty and three years over all Israel and Judah” (2 Samuel 5:4-5).

As king, David’s first priority was Jerusalem. He was aware of Jerusalem’s strategic situation between Israel and Judah, its impressive fortifications and, most importantly, its illustrious history with Melchizedek, Abraham and Isaac. This city had to be Israel’s capital. There was only one problem: Jebus, as it was then called, was inhabited by the Jebusites, a Canaanite people who boasted that they would never be removed.

David was undeterred. He captured the city by sending soldiers through a water conduit. From then on, the city became known as the “City of David.” Jerusalem became Israel’s royal capital. “And David dwelt in the stronghold, and called it the City of David. And David built round about from Millo and inward. And David waxed greater and greater; for the Lord, the God of hosts, was with him” (verses 9-10).

1 Chronicles 18 summarizes King David’s military exploits, including the subjugation of the Philistines (taking Gath) and making the Moabites, Syrians, Ammonites and Edomites tributaries. The inflow of booty from conquered peoples quickly enriched Israel: bronze from Syria, “shields of gold” from Hadarezer (verse 7), and “all kinds of articles of gold, silver, and bronze” (verse 10; nkjv).

Under David, Israel adopted the accoutrements of a true kingdom. 2 Samuel 8:15-18 say it had a standing army, with an organized leadership structure; a ministry of records, with an official recorder; a scribe, a cabinet of ministers, and a well-developed priesthood and religious system.

2 Samuel 6 records David’s greatest accomplishment: relocating the ark of the covenant, a symbol of God’s presence in the nation, to Jerusalem. To house the ark, David petitioned God to let him build a temple (2 Samuel 7), a magnificent building that would glorify God’s greatness, majesty and power.

Territorially, Israel expanded massively under David. The kingdom stretched from near the Euphrates River in the north, to the “Brook of Egypt” in the southwest, to the deserts of Arabia in the east. David conquered most of the remaining territories of Canaan, much of Syria, and the Transjordan peoples (the Edomites, Moabites and Ammonites). Meanwhile, the Phoenician city-states were friends, helping build and develop the nation. “And the Lord gave victory to David whithersoever he went” (2 Samuel 8:6).

When King David died around 971 b.c.e., Israel was well positioned to thrive. After 40 years of fighting untold battles, conquering numerous lands, and suppressing rebellions, the kingdom was ready for peace and stability—and more phenomenal growth.

Solomon’s Rise

Solomon was crowned around 971 b.c.e. at the Gihon Spring. “And Zadok the priest took the horn of oil out of the Tent, and anointed Solomon. And they blew the ram’s horn; and all the people said: ‘Long live King Solomon.’ And all the people came up after him, and the people piped with pipes, and rejoiced with great joy, so that the earth rent with the sound of them” (1 Kings 1:39). His father, King David, heard the celebratory trumpet blasts from his deathbed.

King Solomon made the powerful kingdom he inherited even more expansive and powerful. He began by stamping out every last vestige of rebellion and treason. He secured an alliance with Egypt by marrying the daughter of Pharaoh Siamun (the pharaoh who conquered Gezer and gifted it to Solomon).

Solomon added to Israel’s territory, mainly in the north (Hamath). He consolidated Israel’s control of the Levant, in part by strengthening relations with Phoenicia (1 Kings 5:1) and subjugating local tribes (1 Kings 9:20-21).

Solomon further developed Israel’s government. 1 Kings 4:4-6 show that he had a chief of staff, a ministry of finance and records, a ministry of defense, a ministry of labor and a well-organized department of religion. Israel was divided into 12 districts, each with its own governor. “And Solomon had twelve officers over all Israel, who provided victuals for the king and his household …” (verse 7).

Economically, the kingdom thrived. Subjugating the surrounding nations meant that Solomon now controlled the two main trade routes connecting Egypt to Mesopotamia. This provided a huge boost of revenue into state coffers, allowing for a new monumental building program.

Solomon had a first-class merchant navy that sailed the known world, shipping gold, silver, ivory, apes and peacocks back to Jerusalem. His fleets were divided between the Red Sea in the south and the Mediterranean Sea to the west (1 Kings 9:26-28; 10:22-23). Israel’s king became a major arms manufacturer and a merchant man, importing goods from Egypt, and selling chariots and horses to kingdoms as far north as Turkey (verses 28-29). More than 20 tons of gold were imported every year (verse 14). Silver was so common that it became worthless (2 Chronicles 9:20, 27).

Famously, Solomon married 700 wives, many from faraway exotic lands. Many were likely the result of a political alliance, giving Solomon influence in Egypt, Moab, Ammon, Edom, Zidon, Turkey and elsewhere (1 Kings 11:1-3). All of these peoples—from the Ethiopians to the Zidonians to the Arabians, “all the kings of the earth”—brought gifts of all types to Solomon (2 Chronicles 9:14, 23-24). The Bible declares that the “riches and wisdom” of Solomon were unmatched by any king during his lifetime. “[A]nd his fame was in all the nations round about. … So king Solomon exceeded all the kings of the earth in riches and in wisdom. And all the earth sought the presence of Solomon, to hear his wisdom, which God had put in his heart” (1 Kings 5:11; 10:23-24).

Solomon was an ambitious and lavish builder. He expanded Jerusalem considerably, constructing another palace, an immense armory and imposing fortified walls. All this was accomplished through an extensive organized workforce. “And this is the account of the levy which King Solomon raised; to build the house of the Lord, and his own house, and Millo, and the wall of Jerusalem, and Hazor, and Megiddo, and Gezer. … And Solomon built Gezer, and Beth-horon the nether, Baalath, and Tadmor in the wilderness, in the land, and all the store-cities that Solomon had, and the cities for his chariots, and the cities for his horsemen, and that which Solomon desired to build for his pleasure in Jerusalem, and in Lebanon, and in all the land of his dominion” (1 Kings 9:15-23).

The crowning achievement of Solomon’s reign was the construction of the temple in Jerusalem. His father had spent the final years of his life planning for this magnificent structure. He aimed to make it the pinnacle of architecture, beauty and brilliance. Just before he died, he told his son: “Take heed now; for the Lord hath chosen thee to build a house for the sanctuary; be strong, and do it” (1 Chronicles 28:10). This would be Solomon’s most important and impressive task.

David spared no effort in his preparation for the temple, and Solomon was equally unreserved in its construction. It could arguably be the most impressive structure ever built. This gold-gilded temple must have been a veritable wonder of the ancient world. In today’s money, the value of just the gold (according to 1 Chronicles 22:14, “a hundred thousand talents” worth) has been estimated at around $300 billion.

The dedication of the temple was an earthshaking occasion. “Now when Solomon had made an end of praying, the fire came down from heaven, and consumed the burnt-offering and the sacrifices; and the glory of the Lord filled the house” (2 Chronicles 7:1). This holy structure was the crown jewel of the kingdom of Israel.

Solomon’s kingdom, according to the biblical account, was renowned far and wide. Leaders and representatives traveled great distances to pay their respects to Israel’s king and to see his kingdom.

In the full picture view provided by the Bible, the 10th-century b.c.e. kingdom of Israel truly was a monumental empire—unmatched in the world at the time.

Sidebar: Definitions

United monarchy: This term refers to the kingdom of Israel during the reigns of Saul, David and Solomon, when all 12 tribes were united as one nation under a single monarchy. (The “divided monarchy” refers to Israel following Solomon’s death, when the kingdom split into two separate entities ruled by two separate monarchies.)

Levant: This is the region along the eastern edge of the Mediterranean that constitutes the modern-day nations of Israel, Jordan, Lebanon and Syria.

Why b.c.e., not b.c.: The Armstrong Institute of Biblical Archaeology uses the b.c.e./c.e. appellation mainly because we are an Israel-based organization with a large Jewish audience, and this is the conventional terminology used in Israel and by a large body of our audience.

This is not the only reason we use the “common era” dating. While the use of b.c. (“Before Christ”) and a.d. (“In the Year of the Lord”) is widespread and common, the “common era” terminology (b.c.e. and c.e.) is, technically, more accurate.

Why the JPS: We use the 1917 Jewish Publication Society version of the Bible for most of our scriptural references (unless otherwise noted). The primary reason is that a significant portion of our audience is Jewish. The King James Version is the most popular translation used elsewhere around the world, yet the 1917 JPS gives us the best of both worlds, with direct similarities in language and style to the KJV. Note: While chapter and verse numbering in the JPS usually matches scriptural citations in many other English translations, in some instances it doesn’t.