To use b.c./a.d. terminology, or b.c.e./c.e.? It’s a sometimes hotly contested debate. Both are terminology used for the dating system of our western Gregorian calendar, an “Anno Domini” calendar (a.d.; Latin for “in the year of the Lord”) centered on the birth of Jesus. Thus, this year, a.d. 2023, would literally be considered “the 2023rd year of the Lord.” (Contrary to a popular belief, a.d. does not mean “after death.”) All years prior have a “Before Christ” appellation (b.c.). This one, randomly, is a strictly English abbreviation; the rarely seen Latin equivalent is a.c.n.—“ante Christum natum.”

The language often alternately used for this same calendar system, however—particularly in academia and non-Christian countries—is b.c.e./c.e. These are somewhat more dry abbreviations for “Before Common Era” and “Common Era.” But again, they are hinged on the very same dating system.

Of course, our calendar system is just one of a number of different dating systems around the world. The Islamic Hijri Calendar uses a b.h./a.h. system centered on the Gregorian year 622 a.d./c.e., when Muhammad and his followers migrated to Medina from Mecca, establishing a Muslim community. (b.h. stands for “Before the Hijra,” and a.h. is the Latin equivalent for Anno Hegirae—“in the year of the Hijra.”) A traditional rabbinic Hebrew year-numbering system is an a.m. calendar, figured from Creation (a.m. for the Latin Anno Mundi, “in the year of the world”). This current Hebrew calendar year is a.m. 5783 (“in the 5783rd year of the world”; though, see our article “The Hebrew Year 5783—Or Is It?” for an interesting—and rather consequential—debate about this topic). There are dozens of other dating systems in use around the world, centered on various other anchor points.

Additionally, for dating in extreme antiquity—i.e. tens of thousands of years ago or more—b.p. is often used in scientific circles, an abbreviation for “Before Present.” While this can basically be considered as a count backward from the present day (i.e. such roughly rounded numbers as 10,000 b.p. are essentially 10,000 years ago, or the general equivalent of 8000 b.c./b.c.e.), given that the “present” naturally continues to change, this b.p. system is technically fixed to January 1, 1950 (a specific date connected to the development of radiocarbon dating).

But what of the b.c./a.d., b.c.e./c.e. debate? The latter’s use is certainly found often in scholarship and in non-Christian countries, and is sometimes decried as an overt modern attempt to “excise Jesus” from a dating system still anchored to his birth and overwrite it with more “neutral” or “inclusive” terminology.

Is it a fair condemnation? Actually, there is more to this than meets the eye.

Our regular readers will be aware that here at the Armstrong Institute of Biblical Archaeology, as the standard for our publications, we use the b.c.e./c.e. convention.

One reason for our use of this terminology is that we are an Israel-based organization with a large Jewish audience, and this is a standard convention in the nation and to a large body of our audience. (It is for this same reason that our default English Bible translation used on the website, unless otherwise stated, is the Jewish Publication Society translation, as this is a common translation utilized by many of our readers.) When it comes to the dating debate, in similar manner, if we were a China-based organization, we would use the 公元 dating terminology—this is their international calendar system, which is likewise based on the Gregorian numbering system. Like c.e., 公元 also literally means “Common Era.”

But there is another interesting (and somewhat more involved) angle for the use of this system. This is that “Common Era” is actually a more accurate title for this system than “Before Christ” (b.c.) and “In the Year of the Lord” (a.d.).

Despite the allegation that b.c.e./c.e. takes “Christ” out of the dating system, even from a Christian theological standpoint, he was never in it to begin with. That’s because it is impossible to reconcile this system with the birth of Jesus. In fact, in numerous instances, this calendar system stands in direct contrast to details contained within the New Testament. This has long been recognized by historians and theologians, and from many different angles.

Take the following example. In the New Testament book of Matthew, chapter 2, King Herod is described as reigning in Judah and seeking to kill Jesus after he had been born. Joseph is told in a dream to take his wife Mary and the young Jesus down into Egypt for a time, until the maniacal Herod’s death—following which, they returned to Judea. (The book of Luke also independently places the birth of Jesus during the reign of Herod the Great.)

There’s one problem, though: Herod died circa 4 b.c.e.

Actually, there is debate surrounding the date of his death. 4 b.c.e. is arguably the most widely accepted. Nevertheless, all of the theories—even the latest of them—put the king’s death in “b.c.”—before the Anno Domini calendar’s “birth of Christ” in a.d. 1!

Thus, from a Christian perspective, the b.c./a.d. dating terminology in a sense voids from the outset the authenticity and historicity of the Matthew 2 account. Because of this account (and other details highlighted in the New Testament), a primary theory is that Jesus was actually born around 4 b.c.e.—four years “Before Christ”!

Since the writing of this article, this question of dating terminology was addressed in the following video by Dr. Rob Cargill. “Have you ever wondered why scholars, including biblical scholars, use the terms b.c.e. and c.e. … instead of the traditional b.c. and a.d.?” he asks. “Is it because they hate religion, and are anti-Christian pagans who want to see the demise of all things Christian? Not at all. It has to do with a mistake that was made with the very creation of the Gregorian calendar,” he states, proceeding to explain several issues with it, including the above-mentioned Matthew 2 contradiction.

Now, one solution is to ignore facts, and history, and archaeology, and just keep using the traditional calendar and say b.c. and a.d., and argue that anyone who doesn’t use these terms is anti-Christian. … Or, we can re-date every single date you’ve ever learned, including your own birthday, and memorize new years for every historical event, so that we can accurately continue to use b.c. and a.d. Or, we can do what many devout people of faith, including most biblical scholars, do and just change b.c. to b.c.e., or “Before Common Era,” and a.d. to c.e., or “Common Era,” and just keep using the same calendar [numbers] that we’ve been using.

He concludes: “This is why both scientists and biblical scholars use the terms b.c.e. and c.e. It’s not because they don’t like Christianity. It’s because they like to avoid mistakes, and miscalculations, and historically problematic issues whenever possible.”

And the use of this terminology is certainly not a “modern” convention. In fact, the first recognized use of the “b.c.e.” and “c.e.” equivalent is in 1615, in the writings of the famous German astronomer Johannes Kepler—himself a devout Christian scientist, who studied in depth into the question of the year of Jesus’ birth and participated in deliberations about the introduction of Pope Gregory’s reformed calendar.

Another observation in this whole discussion is that this very calendar system that the year numberings are built into is inherently pre-Christian, pagan Roman in nature. The starting point for the Anno Domini calendar is a Roman convention, centered on the dead of winter. This is in stark contrast, for example, to the biblical start of the year in spring, on the 1st of Abib/Nisan (as outlined, together with the religious festivals, in Leviticus 23).

This mid-winter convention is based on the Julian calendar, which started the year on January 1 (the feast of the two-faced god Janus). This calendar was implemented in 45 b.c.e. during the reign of Julius Caesar. The first-century b.c.e. Roman poet, Ovid, credits the practice of beginning the year in January back to the year 450 b.c.e.—Plutarch and Macrobius, as far back as 713 b.c.e. Thus, it could be considered that our calendar is no more intrinsically Christian than it is pagan Roman—and is arguably more the latter, given its lack of alignment with Jesus himself!

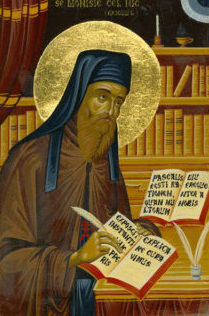

The Anno Domini calendar was actually conceived as late as 525 c.e. by the monk Dionysius Exiguus, and it did not gain widespread acceptance until the ninth century c.e. during the reign of the notorious Holy Roman Emperor Charlemagne (who famously converted Europe to his brand of Christianity “at the point of the sword”). Charlemagne was heavily influential in promoting the calendrical system.

Exiguus’s original calendar had been devised in order to enumerate years for his “Easter table,” as a replacement for the earlier Diocletian calendar, an Anno Martyrum (“Era of the Martyrs”) calendar used from the fourth century c.e. onward. Other (and prior) conventions were to use calendars based on the names of Roman consuls, or the ab urbe condita system—“from the founding of the city,” Rome (in 753 b.c.e.).

Besides error in attempting to anchor his dating system to the birth of Jesus, confusion reigns as to various aspects of Exiguus’s Anno Domini calendar. For example, even whether it was intended to relate to the year of Jesus’ conception or his birth is unclear. Today, December 25 is generally celebrated as the birthday of Jesus in the West, with January 6 traditionally celebrated in Eastern Orthodoxy. (The former would not pose an issue to this question, resulting in a conception and birth in the same year; the latter would.) Of course, neither of these dates—nor Mary’s conception of Jesus nine months earlier, sometime in March/April—accord with the dead-of-winter anchor point for the calendar. Nor do these traditional dates (of December 25 and January 6) accord anywhere near to the time of year of Jesus’ birth alluded to in the New Testament, which appears to have been sometime in the fall. (There’s actually a specific—and perhaps surprising—Roman connection for such dating of the birth of Jesus. See here for more on this subject.)

Another interesting and related theological angle is that in the New Testament, Jesus is cited repeatedly requiring the commemoration of his crucifixion—never his birthday (or birth year). Hence the level of ambiguity and debate swirling around his birth date: It is a detail simply not afforded importance in the New Testament account. The Jewish historian of the same century, Josephus—in the context of describing various Jewish laws—relayed that “the law does not permit us to make festivals at the birth of our children” (Against Apion, 2.26. This statement was probably due in part to every mention in the Bible of birthday celebrations as something being practiced in a sinful context, never in a righteous one—as well as, in every case, a related tragedy occurring). Yet ironically, the single most widely observed event in the world is not the crucifixion date outlined by Jesus in the New Testament, but rather his “birth date” during this peculiar dead-of-winter time frame. So much so, that our entire Western calendrical system is also centered around this inherently flawed a.d. 1 “birth year” assumption.

Using b.c.e./c.e. terminology, then, is technically more semantically accurate. It sees this dating system as it is—a “common” system—yet definitively not one that is anchored “in the year of the Lord.” If anything, rather than taking “Christ” out of the dating system, it takes Exiguus’s flawed—and more importantly, downright misleading—conclusions out of it, yet preserves the same commonly accepted and understood, established numbering system.