What, exactly, is an ophel? It’s a term that we, as excavators of Jerusalem’s Ophel, can easily take for granted. Broadly speaking, in the modern vernacular, the term is generally used to refer to the area between the City of David (to the south) and the Temple Mount (to the north). These two terms—City of David and Temple Mount—are, of course, simple and self-explanatory. The City of David refers to David’s city, the original citadel that he conquered from the Jebusites (2 Samuel 5:7). The name Temple Mount simply implies a mount on which the temple was built.

But the word ophel, found several times throughout the Bible, is not such an easily understood term—certainly not in English and, to an extent, not in the modern Hebrew vernacular either.

What does the word mean? And what does this biblical geographic reference specifically refer to? The biblical word ophel is primarily used to describe a location within Jerusalem. But there are other regional “ophels” mentioned in the Bible and attested to by archaeology. In parsing the clues found in the biblical account, together with references in classical history and on a particular ancient artifact, we can arrive at a satisfactory explanation for the term, as well as the identification of the part of Jerusalem described as such—the Ophel.

Uses of the Term

The term ophel, in Hebrew, is made up of three (sometimes four) letters (עפל, or עופל). In many Bible translations, the proper noun can be found transliterated five times, all referring to the same specific geographic location within Jerusalem. As below:

2 Chronicles 27:3: “He [Jotham] built the upper gate of the house of the Lord, and on the wall of Ophel he built much.”

2 Chronicles 33:14: “… he [Manasseh] compassed [a wall] about Ophel, and raised it up a very great height ….”

Nehemiah 3:26: “Now the Nethinim dwelt in Ophel, unto the place over against the water gate toward the east ….”

Nehemiah 3:27: “… the Tekoites repaired another portion, over against the great tower that standeth out, and unto the wall of Ophel.”

Nehemiah 11:21: “But the Nethinim dwelt in Ophel ….”

These are the more obvious references to this tract of land. There are also several additional buried references to the Ophel, using exactly the same Hebrew word, but which some translations choose to render differently. For example, Isaiah 32:14 reads, “For the palace shall be forsaken; The city with its stir shall be deserted; The mound [Ophel] and the tower shall be for dens for ever ….” In Micah 4:8, the prophet writes: “And thou, Migdal-eder, the hill [ophel] of the daughter of Zion ….”

These alternate translations for the term clearly refer to the Ophel as some sort of prominent mound or hill. But the meaning of this word encompasses more than just geography.

Of Hemorrhoids and Vanity

The Hebrew term for the Ophel also describes a medical condition.

1 Samuel 5-6 tell the story of the capture of the ark of the covenant by the Philistines during the time of the judges and the curses that befell them, including plagues of mice and “emerods”—otherwise translated as tumors or buboes. (“Emerods” is the archaic English term for hemorrhoids. Actually, this biblical account is almost akin to the image portrayed of the Bubonic plague in the Middle Ages—mice and buboes.) The Hebrew word for this disease is spelled in exactly the same way as our geographical Ophel (עפל), and however you prefer to translate it into English, it evidently refers to the same thing—a raised swelling, or a swollen mound.

Deuteronomy 28:27 also references such a disease in connection with Egypt, using the same terminology. When put into these terms of physical disease, the meaning of “ophel” becomes easy (if unpleasant) to conceptualize. Interpolating this onto a much larger scale, an ophel logically refers to some form of a large, prominently raised mound or hill within a city—an upper, fortified area or acropolis.

Another case of slightly different, yet still conceptually related, illustrative terminology can be found in Habakkuk 2:4 (this time with the equivalent verb form of the word, ophla): “Behold, his soul is puffed up [ophla], it is not upright in him ….”

Again, this is apt imagery for a geographical equivalent—a raised, elevated, prominent part of Jerusalem.

But not just Jerusalem.

Other Ophels?

While the majority of biblical references to an ophel relate directly to Jerusalem, this term is used in relation to sites beyond the capital. The account in 2 Kings 5, for example, describes the visit of a leprosy-riddled Syrian captain, Naaman, to Elisha and his servant Gehazi at Samaria (verse 3). Verse 24 contains the following tidbit: “And when he [Naaman] came to the hill [ophel] ….”

Now this is interesting. We have an ophel of Jerusalem and an ophel of Samaria. But there’s more—this time, from an archaeological angle.

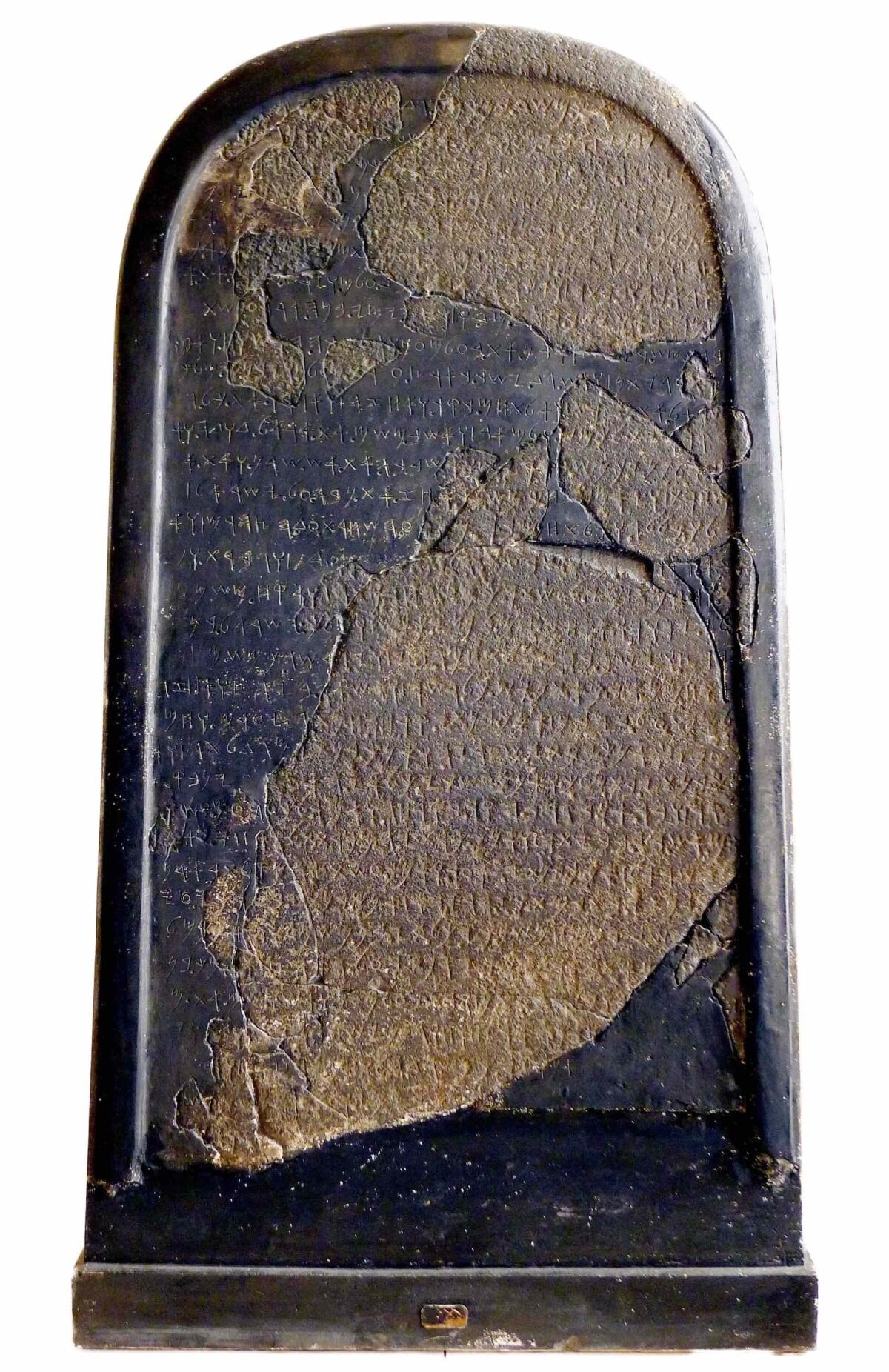

The Mesha Stele, now on display in Paris’s Louvre Museum, is one of the most significant artifacts in the world of biblical archaeology. Discovered in the ancient Moabite capital of Dibon (modern-day Dhiban, Jordan) during the mid-19th century, this large basalt monument is a victory inscription belonging to the Moabite King Mesha, the same individual described in 2 Kings 3. The 34-line, ninth-century b.c.e. inscription contains numerous parallels to the biblical account, including references to biblical kings Mesha of Moab and Omri of Israel, to the tribe of Gad, to various cities and events paralleling the biblical account, and even a reference to King David (something first suspected some 30 years ago, and recently corroborated by new, 3d digital imaging).

But there is another significant, yet often overlooked, reference in the text. Mesha declares, in part: “I have built Karchoh[?], the wall of the woods and the wall of the citadel [ophel] ….”

The late archaeologist Dr. Eilat Mazar was one of the chief excavators of Jerusalem’s Ophel. In Discovering the Solomonic Wall in Jerusalem, she explained both the meaning and significance of the term. Importantly, Mazar noted that the term refers specifically to territory within the capital cities of their respective nation-states.

“When we looked for other cities that used the term ophel, we found that this term was used for only two more capital cities … the first is Samaria, capital of the kingdom of Israel (2 Kings 5:24); while the second comes from the Mesha Stele …. Among his other construction enterprises, Mesha described the construction of ‘the wall of the Ophel’ in Dibon, his capital, giving us the earliest recorded mention of ophel outside the Bible,” she wrote.

“As we see, there were Ophels in at least three capital cities during approximately the same time period: Jerusalem, Samaria and Dibon,” she continued. “It seems that the term ophel was specific to capital cities and their acropolises, in which the king’s palace and other royal buildings, along with the dwellings of the elites, would be located” (emphasis added throughout).

Ophel = Acropolis

Dr. Mazar often referred to the “Ophel” in terms of a royal acropolis—a prominent, royal part of a city raised to a greater height than its surrounds. (Recall the statement in 2 Chronicles 33:14, which notes that King Manasseh “compassed [a wall] about Ophel, and raised it up a very great height.”)

Naturally, the word “acropolis” vividly brings to mind the great Acropolis of Athens—a gigantic elevated geographic “mound” (in this case, more like a mountain), that during various periods contained the royal and religious precincts of the wider city below that it towered over.

Various researchers have actually compared the layout of the Acropolis in Athens to that of Jerusalem. But could there be a greater connection for the use of this terminology—“acropolis”? The Greek term is a conjunction of the words akros (meaning “highest”) and polis (typically taken to mean “city”). The latter element, minus its Greek suffix, looks suspiciously like its Hebrew counterpart (and there is an abundance of such linguistic connections between the ancient Hebrew and Greek worlds). From Routledge’s Encyclopedia of the City, on the original meaning of the term polis: “In ancient Greece, it defined the administrative and religious city center (polis—acropolis), as distinct from the rest of the city, which, as a whole, was called ‘asty’ (better translated as ‘urban’).” An apt definition, it might be said, of the Hebrew Ophel.

In summary, the biblical use of the term ophel describes a geographically raised royal acropolis area—and not just for any city within the nation, but in particular the capital city of a given state—a plot that contained the administrative, royal and, in some cases, religious quarter of the city.

Armed with this knowledge, can we apply it accurately to the topography of Jerusalem to find out where exactly this biblical location was?

Locating Jerusalem’s Ophel

Logically, Jerusalem’s ancient Ophel should be found in or around an upper part of the original ancient city. In the case of Jerusalem’s geography, this would best pertain to the northern end of the eastern hill, due north of the lower City of David ridge. This is the region in which the biblical King Solomon expanded the city to the north following the rule of his father, King David. It is in this northern, raised part of the city that Solomon is described as constructing three major edifices: the temple, his own administrative palace and the enigmatic “house of the forest of Lebanon.” (Interestingly, on the Mesha Stele, within the same sentence as Mesha’s description of his construction of the Dibon Ophel, it also describes the construction of a “wall of the woods”—יער—the very same word as that of Solomon’s “house of the forest.” As such, it is surely more than coincidence that such structures should be found in association with an ophel, or royal acropolis, and probably had some kind of parallel function.)

The Temple Mount complex, of course, is easily recognizable as a raised feature in contrast to the lower City of David. But so too is the area immediately to its south, along the southern wall of the Temple Mount. Today this area may not seem prominent, especially in relation to the Temple Mount; this is because this part of the city now lies destitute and in ruins (particularly as compared to the tall, later-period walls surrounding the Temple Mount). But even today, visitors to the area can get a sense of the natural, sharp elevation of the bedrock while touring along this eastern part of the southern wall of the Temple Mount.

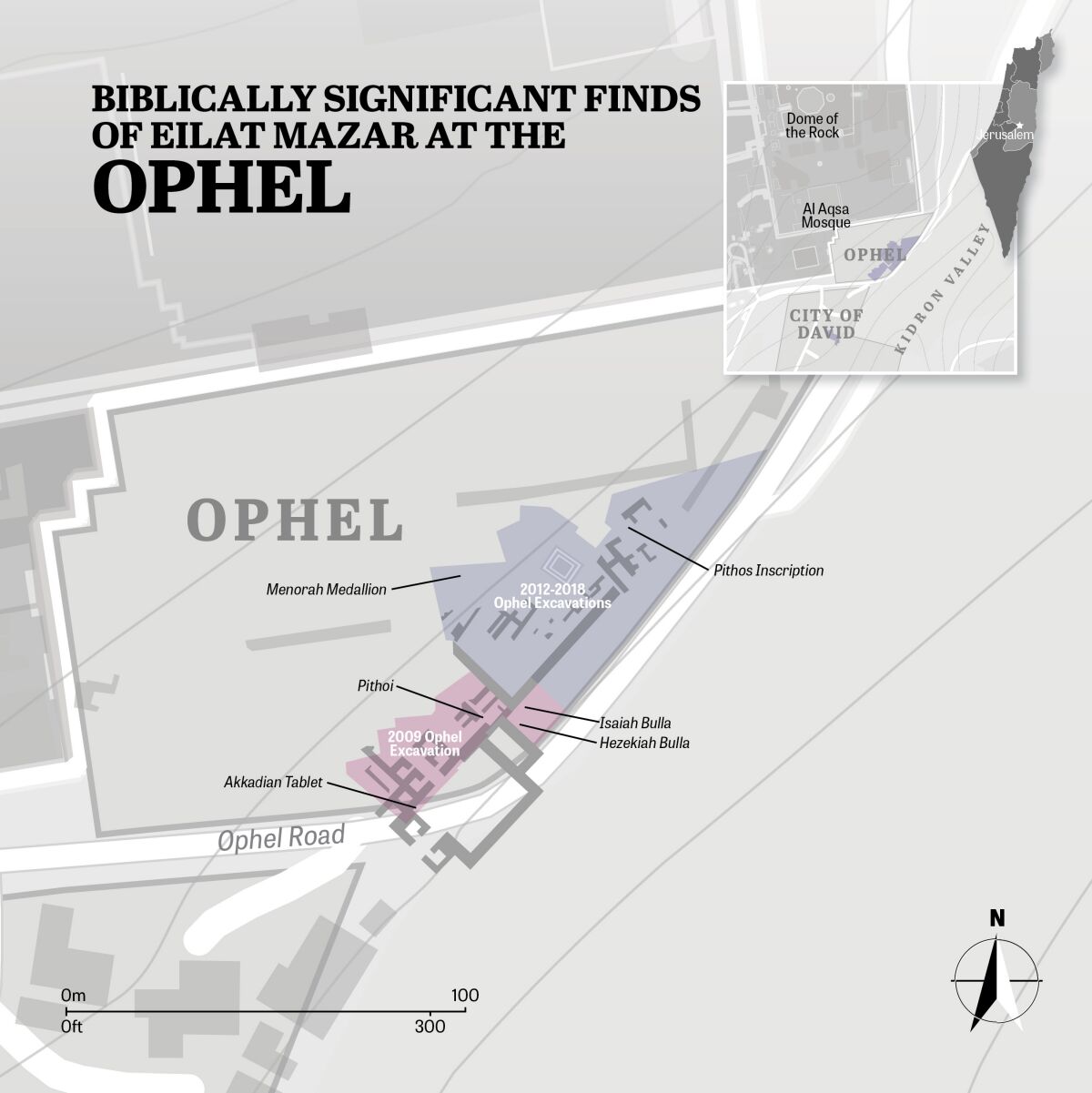

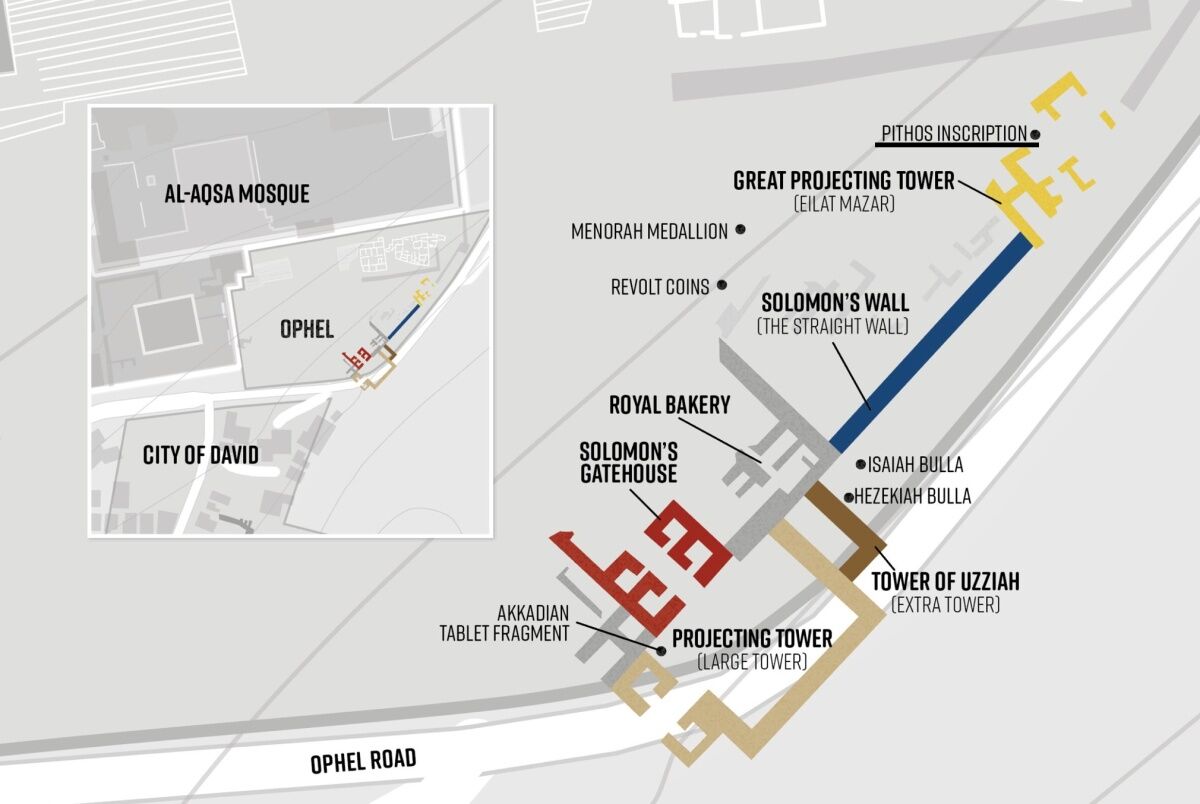

It was over the course of excavations in this eastern area that Dr. Eilat Mazar uncovered the remains of what she termed the “Royal Quarter” of ancient Jerusalem, including a grand gatehouse, raised fortifications, inscriptions (including the seal stamps of King Hezekiah and Isaiah) and a royal bakery. This area she identified as the general location of the palace complex of Solomon and later kings—on this northeastern, raised upper portion of the city, overlooking the Kidron Valley and City of David below.

To this end, the first-century historian Josephus made two references to the location of the Ophel, or the “Ophla”/“Ophlas” (as he rendered it in the Greek language). In describing the area in the context of the Great Revolt, he wrote: “But John held the temple, and the parts thereto adjoining, for a great way, as also Ophla, and the valley called the Valley of Cedron” (Wars of the Jews, 5.6.1).

He further described the defensive walls the Romans came up against, particularly the original inner one: “Now of these three walls, the old one was hard to be taken, both by reason of the valleys, and of that hill on which it was built …. [I]t was also built very strong; because David and Solomon, and the following kings, were very zealous about this work. Now that wall began on the north ….” Josephus continued to describe the directional winding of the wall, before writing: “[A]fter that it went southward, having its bending above the fountain Siloam, where it also bends again towards the east at Solomon’s pool, and reaches as far as a certain place which they called Ophlas, where it was joined to the eastern cloister of the temple” (ibid, 5.4.2).

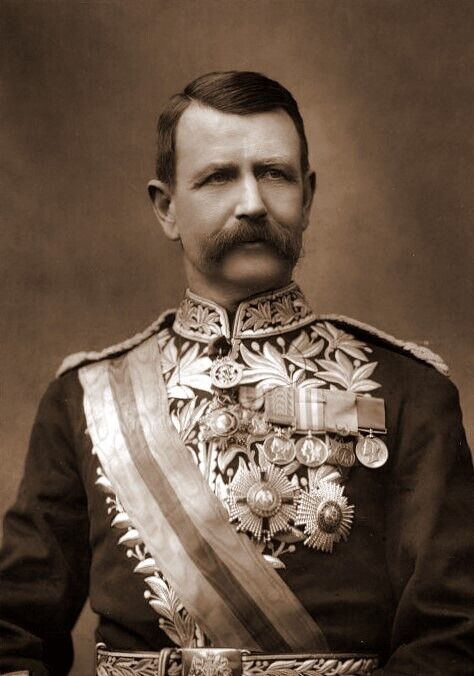

This aptly describes Jerusalem’s Ophel, again, in this very location—the northeastern part of Jerusalem, overlooking the Kidron Valley, against the eastern side of the temple compound. (Based on such information, it was the famous 19th century archaeologist Sir Charles Warren, the first to excavate this area, who was the first in modern times to specifically identify it as such—the Ophel.)

Actually, it is quite possible that the original biblical term was used to include all or part of the temple area. In the Hebrew Bible, the terminology for Temple Mount (הר הבית) is hardly ever used, and where it is found, its meaning is somewhat more general (as in Micah 3:12, Jeremiah 26:18 and Ezekiel 43:12). As such, and given that ancient royal acropolises included the religious compound, it is quite possible that the biblical use of the term ophel also originally designated the temple area as well. This would make sense based on 2 Chronicles 33:14’s account of Manasseh building a fortification wall around the Ophel (certainly, such a wall would not have separated and isolated the temple structure outside the wall, to the north).

But we can get further locational information from the other biblical references as well. Repeatedly, the Ophel is referenced in proximity to the temple complex (e.g. 2 Chronicles 27:3). Nehemiah 3 is a key passage for the identification of landmarks around Jerusalem. It describes, in a counterclockwise manner from the north, the reconstruction of Jerusalem’s wall. Verses 26-27 describe the northeastern part of the city wall. It is in this location that we find three separate mentions of the Ophel (verses 26 and 27, as well as Nehemiah 11:21). Not only that, but we read of this general area as being the location of the “king’s high house” (Nehemiah 3:25; King James Version), a location of priests (verse 28), and specifically a dwelling place for the Nethinim, who played a key role in service to the kings of Judah and in worship service, with a particular focus on the altar (verses 26-27 and 11:21; see also: Joshua 9:27; 1 Chronicles 9:2; Ezra 2:58; 8:20; Nehemiah 7:60; 11:3).

Alongside the “royal quarter” nature of the Ophel excavated by Dr. Eilat Mazar, several further architectural features of this northeastern area were uncovered by her, including what she identified as the “water gate” in Nehemiah 3:26, the “tower that lieth out” (same verse; kjv), the “miktsoa” (a peculiar Hebrew word in verse 25), and Uzziah’s “miktsoa tower” along the same stretch of wall (2 Chronicles 26:9).

In sum, while ophel is overall a more enigmatic term than certain other appellations for Jerusalem, biblical or otherwise, we nevertheless can reach a good understanding of it: an elevated, royal, administrative or religious acropolis of, specifically, a capital city. A designation that, when it comes to Jerusalem, aptly refers to the upper northeastern side of the ancient city, proximate to the temple and including a palatial or administrative royal quarter.