The biblical story of Hagar is well known. Abraham’s wife, Sarah, was unable to bare a child and had reached an old age. Knowing God’s promise of a son, yet doubting the means, she offered her handmaid Hagar to Abraham to serve as a surrogate mother.

And Sarai said unto Abram, Behold now, the Lord hath restrained me from bearing: I pray thee, go in unto my maid; it may be that I may obtain children by her. And Abram hearkened to the voice of Sarai. (Genesis 16:2; King James Version)

This act was clearly against God’s intention. But—as a remarkable new discovery shows—for this time period, it did have legal precedent.

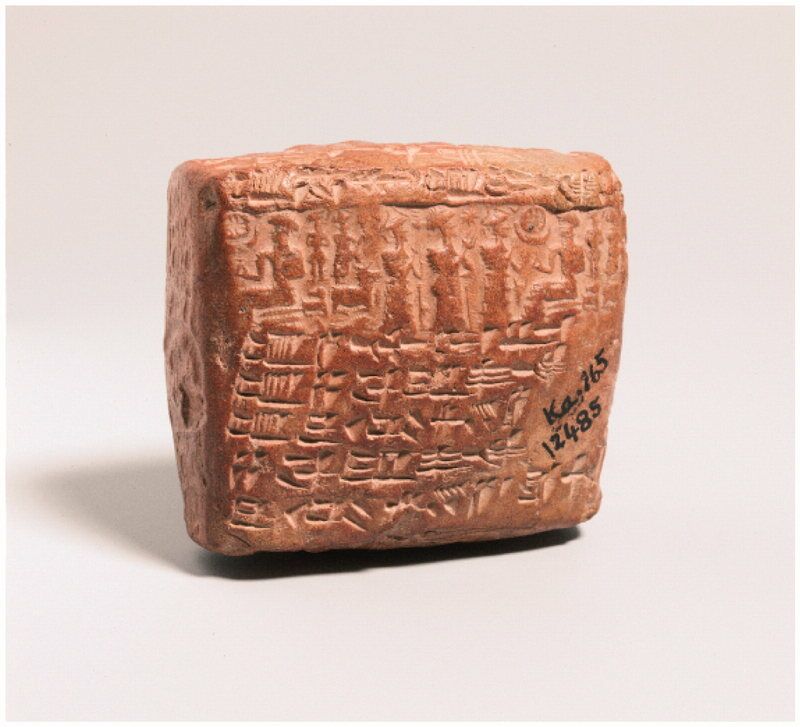

A tablet, written in ancient cuneiform Assyrian script, was recently discovered in Kültepe-Kanesh, Turkey, dating roughly around 2000 b.c.e.—right around the time Abraham was on the scene. The tablet is in the form of a marriage contract, stating that if the couple cannot produce a child after two years, then a slave will be brought in as a surrogate mother to produce a male descendant for the husband and wife. The slave-mother was then to be set free after giving birth to a male.

The tablet is the earliest-known reference to infertility—and its parallels to the story of Hagar are unmistakable.

Clearly, God did not intend for Hagar to be taken in as a surrogate mother. Nor was it biblically lawful. This act, though, was evidently quite legal within Mesopotamia for the time period, and would have been a practice Abraham and his wife were well familiar with—especially considering Abraham was a leading educator within the Babylonian community.

And so—just as this tablet informs us—due to his wife’s infertility, Abraham did “go in unto” the handmaid Hagar, in order for her to produce a legal child for himself and Sarah. However, after Hagar conceived and gave birth to a son, jealousy and discontentment became unbearable within the household. God instructed Abraham that Hagar and Ishmael be released. Interestingly, according to the specific contract on the above tablet, the surrogate mother was to have been freed anyway after giving birth. Perhaps even the pagan Mesopotamian lawmakers had foreseen the potential for severe household conflict. Of course, had it all been done according to God’s purpose from the beginning, this domestic nightmare would never have occurred.

Of further note: The Kültepe-Kanesh marriage contract states that the husband could not marry another woman (Mesopotamians were apparently largely monogamous). The tablet also states that a divorce would cost, in modern value, $1,500.

Regarding monogamy, the Bible shows that Abraham indeed only had one legal wife, Sarah; the same was true for his son Isaac. This, then, paralleled Mesopotamian tradition. (Jacob’s case is somewhat different, however, based on a twisted and manipulated contractual agreement between himself and his uncle Laban—see Genesis 29. The importance and binding nature of contracts in early Mesopotamia is very apparent.)

This new tablet is just one of several such finds that have emerged from Abraham’s time period, corroborating various practices found in the Bible. They are problematic for scholars who radically try to re-date the writing of Genesis to much later periods, in particular to post-captivity (585 b.c.e.). If it were written so much later, how were the fraudulent “ghostwriters” able to accurately document laws so specific to Abraham’s time period, 1,300-plus years earlier? Laws that have now been corroborated, such as slave-mother surrogacy; unusual laws such as the ability to sell one’s birthright; laws allowing one to claim his wife as his “sister” (mentioned three times in the Bible: twice by Abraham and once by Isaac)—during this time period, wives could be legally made “sister” in order to have more rights. How could late writers have known about these traditions and used them for just the right time setting in their writing?

As time goes on, we are finding more and more evidence corroborating the biblical record.

For a more complete review of the composition date of the Torah (including Abraham’s time period), take a look at our article “The Antiquity of the Scriptures: The Torah.”