Originally published on October 1, 2020, as “The Hebrew Year 5781—or Is It?”

The Hebrew calendar is extremely regulated and accurate. Divine and detailed biblical instructions are given for determining months and precisely pinpointing dates, especially for the holy days. The Hebrew calendar is unique in that it is ancient, yet highly advanced and exact. (As headlined by a Haaretz article some years ago, the calendar can be characterized as “A Marvel of Ancient Astronomy and Math.”) It is a combined luni-solar calendar, meaning that it relies on the movements of both the sun and the moon (unlike the solar Gregorian calendar or the lunar Islamic calendar).

Yet while the Bible gives instructions on how to count months and days, it doesn’t specify how to count years. How do we know which year it is on the biblical Hebrew calendar?

Ask many creationists, and they’ll say that Adam was created roughly 6,000 years ago, based upon the chronological information found in the Masoretic text of the Hebrew Bible. (The topic of the “dinosaur age,” naturally, is another matter—as are the different, non-Masoretic chronological schemes, namely those found in the Greek Septuagint and Samaritan Pentateuch.) According to the current, traditionally used Hebrew calendar, which is figured from creation, we have just started the year 5786, beginning on Rosh HaShanah—also called the Feast of Trumpets—this year, beginning the evening of September 22, 2025. The year 5786 is rendered as ה’תשפ”ו in the Hebrew alphanumeric system; תשפ”ו in short form.

How is this date figured? How accurate is it? Does it even matter?

And have you heard of the “missing years” debate that surrounds it—and the dramatic implications thereof?

Counting From Creation

First, again, it is important to understand that the yearly numbering of the Hebrew calendar is not a biblical construct, as are the months and days. Rather, the current Hebrew system of counting years was not established until around 160 c.e., more than half a millennium after the completion of the Hebrew Bible.

This traditional yearly calendar used today in Israel is what is otherwise known as an Anno Mundi calendar (a.m.; Latin for “in the year of the world”). This calendar counts forward from the time of creation to the present day (actually, it is counted from one year before the creation week, starting with a so-called “Year of Emptiness”). The Gregorian calendar, on the other hand, is an Anno Domini calendar (a.d.; Latin for “in the year of the Lord,” otherwise referenced as c.e.) and centers around the birth of Jesus in 1 a.d. (albeit this birth year is widely recognized as wrong; internal New Testament evidence points to a more accurate birth year of 4 b.c.e.).

The traditional Hebrew a.m. calendar comes from the Seder Olam Rabbah (sor), which translates as the “Great Order of the World.” Composed around 160 c.e. by Rabbi Jose ben Halafta, this timeline outlines a chronology from Adam to the Bar Kochba Revolt of 135 c.e. Like the Mishnah, it was compiled at a time of enormous persecution, when it was feared that the Jewish way of life and knowledge faced extinction.

For several centuries after the writing of the sor, there was some confusion among Jewish communities regarding the precise counting of the given dates. In the 12th century c.e., the rabbi Maimonides established a more definitive numbering system based on the sor. This system has been used to today—a.m. 5786. Here is how this is calculated.

3,338 Years to the Destruction

Counting the years from creation, based upon the numbers given in the Masoretic text of the Hebrew Bible, is fairly simple. Genesis 5 gives the genealogy from Adam to Noah. It outlines the lifespan of each individual and, most importantly, how old they were when their respective descendant was born. (Still, it is impossible from this passage to add together these dates to the precise year, i.e. since specific months of birth and death are not provided—therefore, the accumulative sum of months may add up to several additional years.)

Just taking the raw numbers from Adam to the birth of Noah, however, we have 1,056 years. Genesis 7:6 states that “Noah was six hundred years old when the flood of waters was upon the earth,” which takes us to a.m. 1656.

In counting from the Flood, the genealogies in Genesis 11 are turned to. These take us to the days of Abraham, who is in turn attributed the birth date of a.m. 1948. Here again, it is difficult to establish an entirely accurate figure, based again on the potential of accumulative months (for example, if each generation from Adam to Abraham was born six months into the counted year, this would constitute an additional nine years), some debate surrounding the age of Terah when Abram was begotten, etc. Nevertheless, continuing with the raw year information provided, the birth of Isaac is recorded as occurring when “Abraham was a hundred years old”—thus a.m. 2048. So far, so good.

Some difficulty arises during the time period from the patriarchs to the Exodus. The straightforward generational counts stop, and clues must be drawn from other passages. Exodus 12:40 is a much-debated scripture, sometimes taken to mean that the Israelites lived in Egypt from the descent of Jacob and his family to the Exodus for a full 430 years (the Septuagint version reads Egypt and Canaan, implying that this count includes the sojourning in Canaan of the earlier patriarchs). Genesis 15:13 contains a related prophecy of a 400-year period for Abraham’s “seed,” before his descendants would be released from “affliction.” While both accounts end at the Exodus, various sources are at odds as to when to start the 400- and 430-year counts.

The sor calendar takes the 400-year date from Isaac’s birth, when Abraham was 100 (interpreting the “seed” of Genesis 15:13 quite literally as Isaac). A slightly variant calculation, from around a century before the sor calendar was written, is demonstrated in the New Testament—Galatians 3:16-17—which starts the 430-year count from God’s covenant with Abraham. Nonetheless, for our purposes here (and given how relatively close these figures are), we will continue to follow the conventional sor calendar dating (recognizing the potential for discrepancy at this point of up to several dozen years). For a full examination of this sojourn-period debate, see our article “When Was the Age of the Patriarchs?

Four hundred years from Isaac’s birth gives us an sor Exodus date of a.m. 2448. And 1 Kings 6:1 tells us that 480 years passed from the Exodus to the building of the temple, in the fourth year of Solomon’s reign—a.m. 2928. (This period from the Exodus to the temple is another simple biblical calculation, yet comes with a world of theological and archaeological debate—see our article here for more information.)

From this point on, things get even more complex. While the regnal lengths of the kings prior to the destruction of the temple are generally clearly listed, we cannot simply add these numbers back-to-back. It is clear that several co-regencies took place (this is evident from comparing the chronologies of the reigns of the kings of Judah with the kings of Israel, as well as Assyria)—but there is a significant amount of debate as to which kings were co-regent and for how long. Another thing to consider is that since the end of one reign and the beginning of another date to the same year, for every new ruler one year of reign must be removed from the count. Using this rationale (and largely putting aside the co-regency issue), the date for the end of the reign of Judah’s final ruler, King Zedekiah, and the destruction of the temple is traditionally given as a.m. 3338.

Again, this date cannot be definitively known from the Scriptures. So, by this point in the sor calendar, we technically could have plus or minus several decades (and we haven’t even arrived at the “missing years” period yet). Nonetheless, in its most basic form, simply counting the years given, the sor calendar gives the date of the temple’s destruction as a.m. 3338.

One would think that the closer we get to the present, the easier the count would get. But it is from this point forward things get really problematic.

The ‘Missing Years’

The confusion has to do with the length of time between the destruction of the two temples—the first temple (circa 586 b.c.e. on the conventional calendar) and the second temple (70 c.e.).

The destruction of the second temple at the end of the Great Jewish Revolt is widely recognized as dating to 70 c.e. on the Gregorian calendar. Still, there has been some historical rabbinic debate about this—whether it dates to 68, 69 or 70 c.e. The sor calendar recognizes it as the equivalent of 68 c.e.

A number of rabbinic works state that the second temple stood 420 years. Subtracting this from 68–70 c.e., we arrive at around 350 b.c.e. as the date of the building of the second temple by Zerubbabel. The Prophet Jeremiah prophesied that the Jews would return and rebuild that temple 70 years after its original destruction (i.e. Daniel 9:2). This would then place the destruction of Jerusalem and the first temple by the Babylonians at around 420 b.c.e. on the Gregorian calendar, 490 years prior to the destruction of the second temple.

This date—circa 420 b.c.e.—may come as a shock. It is miles off from the general historical, conventional dating of the destruction of the temple, circa 586 b.c.e.—roughly 165 years difference.

In the calendar debate, these are known as the “missing years.”

The date of the fall of Jerusalem and destruction of the temple is absolutely grounded in numerous historical sources, backward and forward, for the conventional calendar. There is some particular debate as to whether it was 587 or 586 b.c.e., but plus or minus a year is negligible. This dating, in the mid-580s, is corroborated by the ancient, detailed chronological texts of Babylon, Egypt, Persia and Greece, as well as early Jewish chronologies (including that of the first century c.e. historian Josephus), and the writings of dozens of other first-millennium b.c.e. historians (all paired with and corroborating biblical chronological timestamps). The traditional sor calendar, on the other hand, stands entirely alone. And the knock-on effects cannot be understated—this results in all history on the sor calendar prior to this point being likewise down-dated by the same length of time (i.e. shifting the reign of David from the early 10th century b.c.e. to the late 800s b.c.e.; shifting Assyria’s invasions and destructions from the late eighth century b.c.e. to the mid-sixth century b.c.e.; and so on—not to mention displacing synchronisms between multiple biblically-attested rulers).

Where, then, did the 165 missing years of the sor calendar go?

Theories

This “discrepancy” has long been accepted as problematic and debated by numerous rabbis and other Jewish authorities. Many theories try to explain it.

One of the most recognized areas of “trouble” is in the biblical listing of Persian kings. The book of Daniel references four Persian kings. Certain Talmudic sages historically took this to mean that there were only four Persian kings, filling a 52-year period. Conventional historical chronologies, however, show that there were in fact 13 Persian kings who ruled over a 207-year period between the Babylonian and Greek empires. This, then, would account for almost all of the discrepancy. (The apparent discrepancy in Daniel is readily explained by the fact that the book merely notes the four most prophetically significant rulers of Persia, and was never intended to give an exhaustive listing of Persian monarchs.)

Another explanation for why the sor gives 490 years between the destruction of the first temple and the second is the 70-weeks prophecy found in Daniel 9. The theory goes that Daniel 9:24-26 were taken to refer to 490 prophetic years between the destruction of the temples.

The passage of Scripture reads:

“Seventy weeks [490 prophetic years, with the biblical day-for-a-year principle; or, the better translation of the specific word “weeks” as “sevens”—seventy seven-year periods] are determined upon thy people and upon thy holy city, to finish the transgression, and to make an end of sins, and to make reconciliation for iniquity, and to bring in everlasting righteousness, and to seal up the vision and prophecy, and to anoint the most Holy. Know therefore and understand, that from the going forth of the commandment to restore and to build Jerusalem unto the Messiah the Prince shall be seven weeks, and threescore and two weeks: the street shall be built again, and the wall, even in troublous times. And after threescore and two weeks shall Messiah be cut off, but not for himself: and the people of the prince that shall come [the Romans] shall destroy the city and the sanctuary” (verses 24-26, kjv).

Christians point to the Daniel 9:24-26 timestamps as aligning with the arrival, ministry and crucifixion of Jesus from the time of the “commandment” to rebuild Jerusalem during the days of Ezra and Nehemiah (Ezra 7:7-28), followed by the later destruction of Jerusalem and the temple at the hands of the Romans. And again, a traditional Jewish explanation for Daniel 9 is as relating to 490 years from the destruction of the first temple to the destruction of the second—an explanation that, again, results in around 165 “missing years” when compared to conventional calendars.

Another related theory for the missing years endorsed by certain Jewish scholars suggests that the statement at the end of the book of Daniel—“shut up the words, and seal the book” (Daniel 12:4)—could have been seen as a command to obscure the calculations of the Messiah’s coming so the time frame would not be known. This could therefore imply a deliberate misrepresentation of the 70-weeks prophecy within the sor calendar dates.

Theories abound as to the explanation for these “missing” 165 years. Rabbi M. Breuer believes the sor count is not factually accurate but is instead supposed to be symbolic. Rabbi B. Wein agrees that the sor count is off but does not know why the ancient writers would have changed the conventional dates; he suggests that the explanation will be given by the Messiah at his coming. Other Jewish scholars and rabbis have explanations.

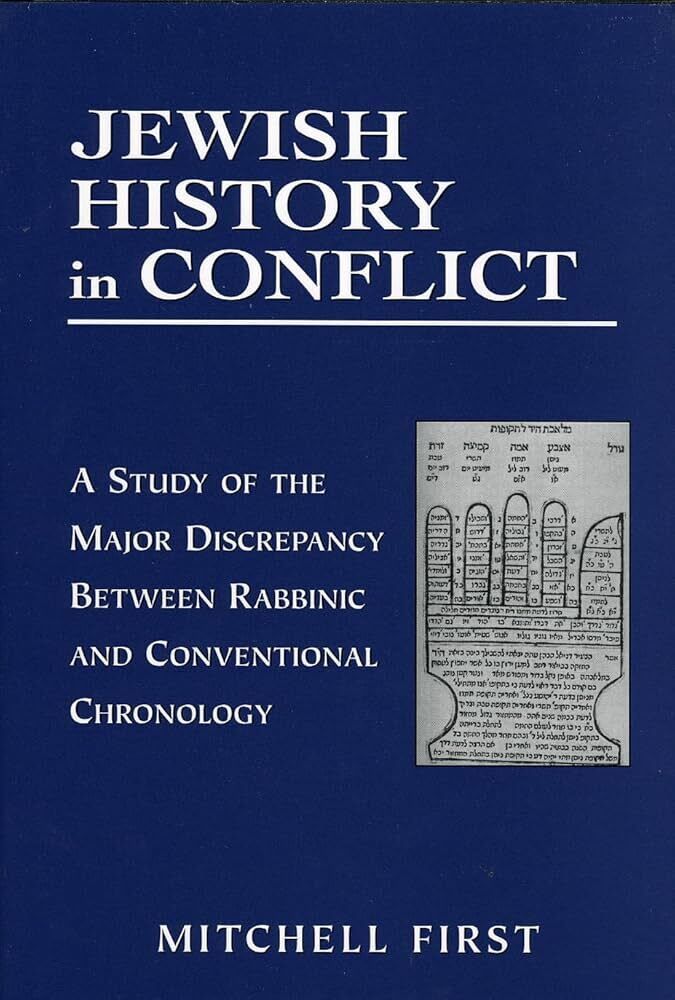

Orthodox Jewish scholar Dr. Mitchell First compiled an exhaustive book on this subject titled Jewish History in Conflict: A Study of the Major Discrepancy Between Rabbinic and Conventional Chronology. He explains this controversy, enumerating these various different Jewish perspectives on it—from the earliest documented explanation (circa 900 c.e.) to the present day. He lists the substantive statements made on the issue by Jewish scholars and rabbis: All totaled, 41 were in favor of the conventional chronology over the sor; 17 were in favor of the sor chronology over the conventional; and 14 made the case that both are correct.

But is the answer to this debate of any real importance?

A Lot Later Than You Might Think

It becomes clear from the overwhelming weight of evidence that the sor is off by close to two centuries. This is shown by a vast number of parallel historical sources, including the earliest Jewish sources—all of which do parallel biblical sources. And as above (and outlined in First’s book), this is a conclusion accepted by a large number, if not a majority, of Jewish authorities. Still, in the name of tradition, the sor calendar continues to be utilized to this day.

But there is another side to the religious importance of accuracy in such calculations.

Both Judaism and various branches of Christianity recognize that the Messiah will come (or in the case of Christianity, return) just prior to, or by, the year 6,000. There are inferences to this in both the Hebrew Bible and New Testament. This is based particularly on several scriptures that use the seven-day week to typify the course of human existence. God accomplished the creation in six days, and “He rested on the seventh day” (Genesis 2:2). Similarly, God commanded man to work six days of the week and rest on the Sabbath (Exodus 20:8-10). The Bible explains that “one day is with the Lord as a thousand years, and a thousand years as one day”—a day-for-1,000-year refrain Moses cites in the Psalms. “For a thousand years in Thy sight Are but as yesterday when it is past …” (Psalm 90:4; parallel New Testament scriptures include 2 Peter 3:8 and Revelation 20:4, which expounds on a seventh-day “millennium” of rule by the Messiah).

Thus, each day of the week has a thousand-year parallel. As another example, note God’s warning to Adam and Eve against eating from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, for “in the day that thou eatest thereof thou shalt surely die” (Genesis 2:17). Of course, they did not die physically within that 24-hour day (though they did incur the penalty of death at that very same time). But consider this in the context of “one day is with the Lord as a thousand years.” Adam died at the age of 930 (Genesis 5:5)—thus indeed dying just inside of that very same millennial “day.”

These day-for-1,000-year epochs, then, finally culminate in the seventh-day, thousand-year “Sabbath of rest” that is the Messiah’s rule.

In the words of the Midrash, “Six eons for going in and coming out, for war and peace. The seventh eon is entirely Shabbat and rest for life everlasting.” The Babylonian Talmud quotes Rabbi Katina: “Six thousand years the world will exist and one [thousand, the seventh], it shall be haruv …. Just as the seventh year is the Shmita [land Sabbath] year, so too does the world have 1,000 years out of seven that are fallow, as it is written, ‘And the Lord alone shall be exalted in that day’ (Isaiah 2:11)” (Sanhedrin 97a).

Thus a weekly, seventh-day Sabbath of rest; a seventh-year land Sabbath of rest (Exodus 23; Leviticus 25; Deuteronomy 15); and a seventh-millennium Sabbath of world “rest.” Numerous later rabbinical Jewish writings mention the 6,000-year “deadline” for the arrival of the Messiah.

Our namesake Herbert W. Armstrong commented on this subject: “That master plan involves a duration of 7,000 years. The seven literal days of creation were a type. … God allotted the first 6,000 years to physical man, to live his own way … to prove by 6,000 years of suffering mountainous evils that only God’s way can bring desired blessings.”

With all this in mind, when we add the “missing years” from the sor, we arrive at an actual “date from creation” of somewhere around a.m. 5950. And when factoring in other unclear numbers, such as a debate about the date of Abraham’s birth—if indeed he was begotten when his father was 70, or if it was several years or even decades later (Genesis 11:26-12:4)—and taking into account the accumulative biblical months related to births, regnal dates, and other potential errors—we are quite conceivably several decades beyond a.m. 5950.

To the non-religious observer, this may mean nothing. But to the religiously concerned, it means everything. And it’s perhaps why the famous 17th century scientist Sir Isaac Newton—a Bible-literalist whose extensive theological writings are lesser-known—believed that our 21st century would see the end of this “present age,” and the beginning of a “new divine era,” the “Kingdom of God.”

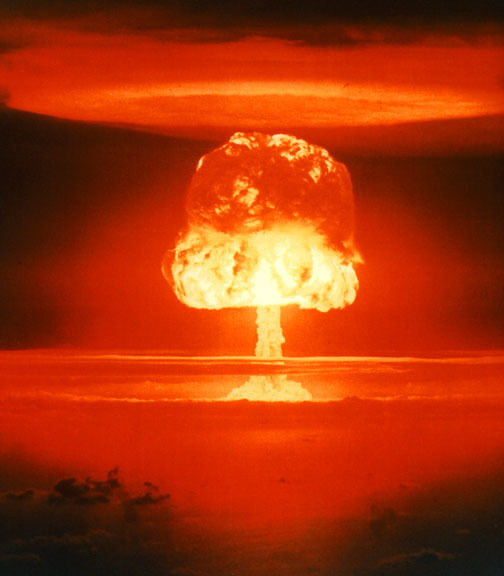

After all, the Bible contains strong warnings about the end of the “age of man.” It describes a time of world war and suffering just prior to the arrival of the Messiah—a “time of trouble, such as never was since there was a nation even to that same time” (Daniel 12:1; see also Jeremiah 30:7). This same theme is carried through the New Testament, with its warnings of fiery destruction so great, that “except those days should be shortened, there should no flesh be saved” (Matthew 24:22). The first century historian Josephus himself noted two prophesied worldwide destructions—one, “by the violence and quantity of water” (Noah’s flood)—and the other, yet future, “by the force of fire” (Antiquities 1.2.3).

One can’t help but wonder: Is it just coincidence that only in the past several decades has mankind developed fiery weapons of mass destruction capable of literally wiping all life off the face of the Earth, multiple times over? J. Robert Oppenheimer famously summed it up, following his role in leading the successful development of the first atomic weapons: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds” (quoting the Bhagavad Gita). Indeed, it is now often stated that our greatest problem today is that of “human survival.”

As the Prophet Daniel continues to describe, the Messiah will come and intervene to stop the madness. Verse 1 continues, with a promise from God to protect His people: “[A]nd at that time thy people shall be delivered, every one that shall be found written in the book.” (In the words of Jeremiah 30:7: “Alas! for that day is great, So that none is like it; And it is a time of trouble unto Jacob, But out of it shall he be saved.”) God then instructs Daniel: “But thou, O Daniel, shut up the words, and seal the book, even to the time of the end; many shall run to and fro, and knowledge shall be increased” (verse 4—the latter part of this verse also uncannily predictive of our modern “Information Age”).

No man can pinpoint the exact date we are at in history. We have established that. What we do know, following the chronology outlined in the Hebrew Bible, is that we are within the final years before a.m. 6000.