“For the king of Babylon standeth at the parting of the way, at the head of the two ways, to use divination; he shaketh the arrows to and fro, he inquireth of the teraphim, he looketh in the liver” (Ezekiel 21:26).

Looking into a liver? It’s a strange passage of Scripture written by the Prophet Ezekiel. But it is one that has now been well-illustrated, thanks to archaeological research (fulfilling words used to describe the foundation of biblical archaeology, as a scientific inquiry “for biblical illustration”).

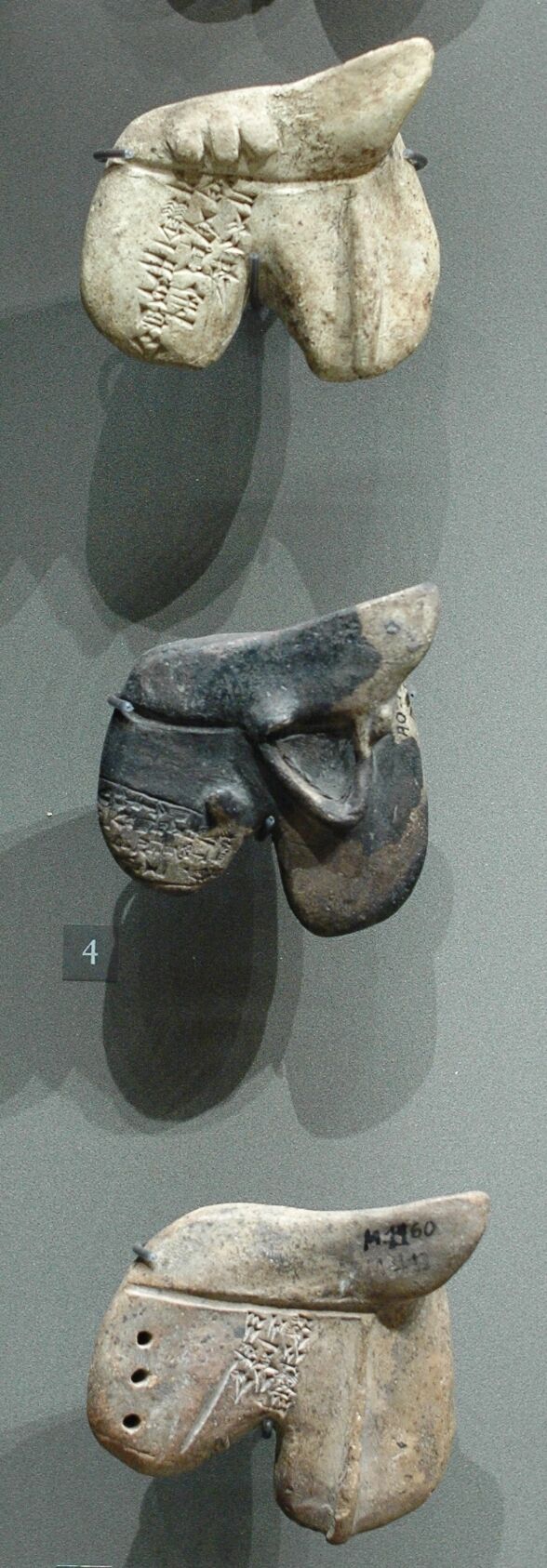

Arguably the best “illustration” of Ezekiel 21:26 (verse 21 in certain other Bible translations) can be found at the British Museum, in the form of a peculiarly shaped piece of clay covered in holes and writing. This artifact is known as the “Liver Tablet.”

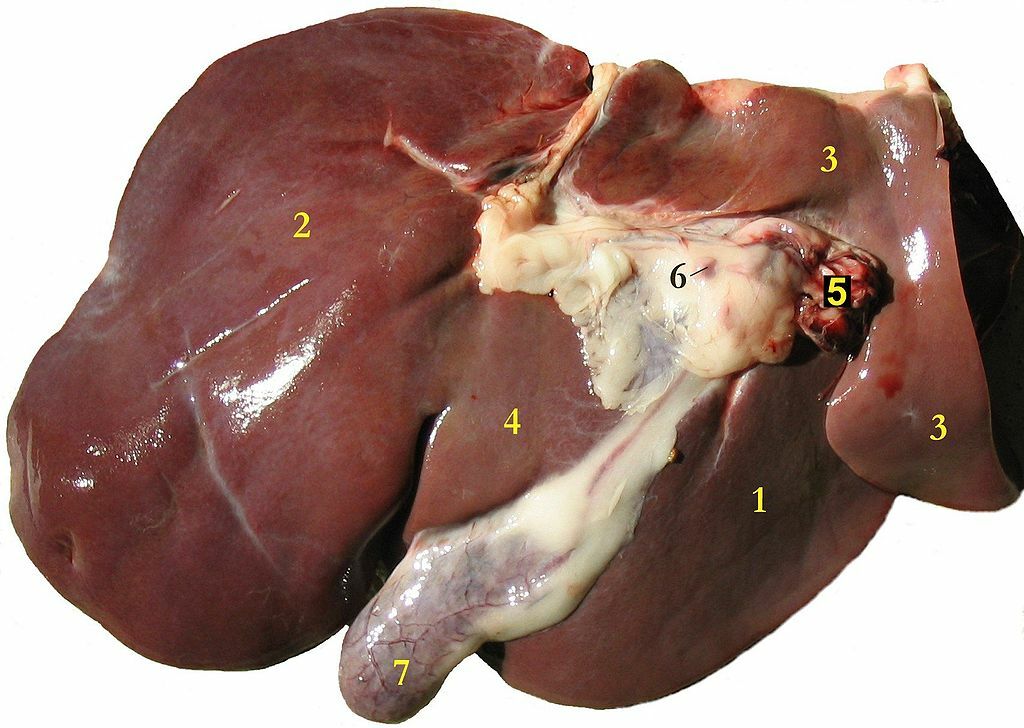

Dating to the Old Babylonian Period (circa 1900–1600 b.c.e.), this tablet is believed to have come from the Babylonian city Sippar (in modern-day Baghdad province, Iraq). It is a clay model of a sheep’s liver, apparently used as a training device for students studying to become a baru priest.

The ancient Babylonians, believing their gods foreknew the future, believed that these gods left clues available in order to predict that future—namely, clues that were contained in the liver of an animal. The Bible affirms that “life … is in the blood” (Genesis 9:4; Leviticus 17:11)—something that has been proved today, with the understanding of the oxygenation of the bloodstream. The Babylonians believed that the liver was the source of that blood, thus the life essence.

With a little mental gymnastics, it thus only made sense to the Babylonians that the selection and slaughtering of just the right sheep (or chicken) and analysis of the liver could determine future events.

The baru priest would present a certain question, and based on the position of certain blemishes on, or the shape of, the liver, an answer would be provided. The British Museum model shows the implication of a certain blemish in any of the 55 different sections. Copious amounts of notes were kept regarding omens relating to livers.

As the British Museum writes of this artifact: “One of the most widespread means of prediction was a liver omen, in which the sheep was killed and its liver and lungs examined by a specialist priest, the baru. … The baru played an important part in decision making at all levels but particularly where the king was concerned. No military campaign, building work, appointment of an official, or matters of the king’s health would be undertaken without consulting the baru.”

Back to Ezekiel, who describes the king of Babylon’s decision-making processes: “For the king of Babylon standeth at the parting of the way, at the head of the two ways, to use divination; he shaketh the arrows to and fro, he inquireth of the teraphim, he looketh in the liver. In his right hand is the lot Jerusalem, to set battering rams, to open the mouth for the slaughter …” (Ezekiel 21:26-27). The Babylonian king, here mentioned just prior to Jerusalem’s fall, is presented with a binary choice—a “crossroads” decision, two paths before him, to advance on Jerusalem or not. In order to decide, one of the methods he uses is to “look in the liver,” likely with the assistance of his baru. The fact that the “lot” ended up “in his right hand” meant that the answer was indeed to go and attack Jerusalem.

Of this passage, Matthew Henry’s commentary states, “The resolution he was hereby brought to. Even by these sinful practices God served His own purposes and directed him to go to Jerusalem.” As verse 28 reads, “And it shall be unto them as a false divination … but it bringeth iniquity to remembrance, that [Jerusalem] may be taken.”

The Babylonian Liver Tablet, then, is a fascinating piece of “Bible illustration,” which can readily be viewed in the Mesopotamian section of the British Museum. And in another manner, it is an illustration of the absurd, groping devotion of the ancient world to inane superstition, likewise described in the Bible (and set in the same time period, just before Jerusalem’s destruction): “[B]e not dismayed at the signs of heaven; For the nations are dismayed at them. For the customs of the peoples are vanity …. [T]hey are altogether brutish and foolish: The vanities by which they are instructed are but a stock …. [The] molten image is falsehood, and there is no breath in them. They are vanity, a work of delusion; In the time of their visitation they shall perish.

“Not like these is the portion of Jacob; For He is the former of all things …. The Lord of hosts is His name” (Jeremiah 10:2-3, 8, 14-16).