Sir Winston S. Churchill once said, “A nation that forgets its past has no future.” By Churchill’s reckoning, Israel is in danger. Perhaps this seems a little extreme, but let me explain.

To Jews and Christians, Israel’s ancient history is the richest in the world. And the primary chronicle of this history, culture and tradition is the Hebrew Bible. The Bible forms the basis of Western civilization, and in some form or other is a foundational religious document for over 4 billion people around the world. Even in this age of intense secularism, the Bible remains the most sold, most owned, most translated, most revered book in human history.

Many Israelis see and understand the centrality of the Bible very well. But in the upper echelons of academia—among many of those entrusted to teach and pass on this ancient history to future generations—the Scriptures are viewed with cynicism and even palpable disdain. Among the “enlightened,” the Bible is now deeply unfashionable. Of course, modern scholarship finds anything religious in nature automatically disdainful. It loathes with religious fervor what it cannot understand: Anything with a whiff of divinity, the miraculous, or the supernatural is anathema. So the Bible is, in principle, flatly dismissed as a serious teaching tool and scientific aid.

Archaeologist Scott Stripling, director of excavations in Tel Shiloh and provost at The Bible Seminary in Texas, alluded to this anti-Bible bias in academia in a June 2019 interview with Eve Harrow. In the interview, Stripling explained that “much of Israeli archaeology has become totally secular.”

Stripling recalled a lecture he delivered some years ago at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in which he discussed the Bible and archaeology. He was speaking to Ph.D. students, all of whom “loved what I was talking about.” Following the lecture, the students told Stripling that he was the “first [lecturer] all year to use the Bible.”

While Dr. Stripling praised the work of Hebrew University, he also said that it was “sad” and “tragic” to see that the Bible was no longer being consulted or featured in its archaeological program. “It is tragic, to have that level of anti-biblical bias,” he said. Stripling said that while not everyone in the community had this anti-Bible view, it was still a “general trend” at the institutions.

When it comes to archaeology, Hebrew University of Jerusalem is easily Israel’s most “conservative” university. The university was once the world’s leading establishment for biblical archaeology. The late Prof. Benjamin Mazar, a former Hebrew University president, is known worldwide as the “dean of biblical archaeologists.” Now, however, anti-Bible sentiment is even more virulent across virtually all of Israel’s institutions of higher learning.

But why does all this matter? What does the Hebrew Bible, an antiquated religious document, have to do with science? Doesn’t the term “biblical archaeology” itself carry an unscientific, preconceived bias? What is biblical archaeology, and is it really that important to the Jewish state today?

Countering the ‘Enlightening’

Even the definition of “biblical archaeology” is somewhat vague. To some, it is simply the excavation of a site or material within Israel, dating to a biblical time period. More properly, biblical archaeology is the practice of archaeology in consultation with the Bible. This might include selecting a site based on the biblical record, or interpreting discoveries in the context of biblical information. Today in Israel, the former method is typically espoused—“biblical” archaeology, only in the sense of a biblical setting and dating. This, of course, is a far cry from what biblical archaeology once was, and what it was designed to be.

Biblical archaeology primarily began as a field of study in the 19th century. The Bible at that time was still a widely respected book, even among scholarly circles. At the start of the century, the assumption of biblical accuracy was actually taken for granted by a great number of Western academics. But as the century progressed, ideas in academia began changing. One of the key areas was the study of origins—in particular, the development of the theory of evolution.

The landmark moment came in 1859, when Charles R. Darwin published On the Origin of Species. This and other evolutionary research highlighted a divide in the scholarly community. Before long, there were two general camps: those who continued to respect the authenticity and usefulness of the biblical account to some degree or other, and those who considered the Hebrew Bible as fable and a hindrance to the purely secular method of science based solely on human reason.

This growing divide was one of the chief reasons for the establishment of the Palestine Exploration Fund, founded in London in 1865. The debate “accelerated a demand for scientific reaffirmation of the authority of the Bible,” wrote P. R. S. Moorey in A Century of Biblical Archaeology. “The Palestine Exploration Fund was not a religious society, though inevitably created under the patronage of the established Church of England. It was intended to provide ‘for the accurate and systematic investigation of the archaeology, topography, geology and physical geography, natural history, manners and customs of the Holy Land, for biblical illustration’” (emphasis added throughout).

The Palestine Exploration Fund became the preeminent British organization for conducting scientific excavations and surveys of the Holy Land (and currently remains the world’s oldest institution for such research, though it is now a much more low-profile organization). The fund’s creators stressed from the start that the organization was not to be a religious one. At its first meeting, Archbishop of York William Thomson stated: “[O]ur object is strictly an inductive inquiry. We are not to be a religious society; we are not about to launch controversy; we are about to apply the rules of science, which are so well understood by us in our branches, to an investigation into the facts concerning the Holy Land.”

This was the genesis of biblical archaeology. And notice, it was a compliment to science. Archbishop Thomson continued to explain the reason for the fund’s creation: “No country should be of so much interest to us as that in which the documents of our faith were written, and the momentous events they describe enacted. At the same time no country more urgently requires illustration …. Even to a casual traveler in the Holy Land the Bible becomes, in its form, and therefore to some extent in its substance, a new book. Much would be gained by … bringing to light the remains of so many races and generations which must lie concealed under the accumulation of rubbish and ruins on which those villages stand.”

The 19th-century British public (and the Western world in general) held dear the history and teachings of the Scriptures. Yet they were thousands of years—and thousands of kilometers—removed from the places and events described in the Bible. As such, scientific expeditions were to be carried out in order to see just what kind of historical corroboration and illustration could be found for the biblical stories.

Early pioneers associated with the efforts included such influential figures as Sir Charles Warren, Sir William Flinders Petrie, R. A. S. Macalister, Sir Leonard Woolley and T. E. Lawrence “of Arabia.”

Mistakes, Solutions

One of the early issues that led to criticism of biblical archaeology revolved around the fact that the field of archaeology itself was still in its infancy. Proper archaeological techniques and standards had not yet been properly established, and the dating of artifacts was at best uncertain. Naturally, mistakes were made, finds were misdated, and sites were sometimes mislabeled. It wasn’t unusual for archaeologists to deliver conflicting conclusions (something we are familiar with even in the 21st century). Although the teething issues afflicted archaeological sites all over the world, the fact that mistakes were being made in the Holy Land provided additional ammunition for the skeptics. Finds that had been mislabeled, misdated, or not fully understood began to be interpreted as evidence against the biblical account.

These sorts of errors were made both before and after the establishment of the Palestinian Exploration Fund. Actually, one of the primary aims of the Palestinian Exploration Fund (pef) was to provide an umbrella organization under which archaeological excavations could be standardized and controlled in order to prevent such mistakes and conflicting reports.

Over time, and especially during the 20th century, archaeological methods in the Holy Land developed in leaps and bounds. In fact, archaeology in Israel began to set the standard for excavations taking place around the world. This was thanks in large part to the biblical archaeologists of the pef—archaeologists such as Petrie (the “father of Palestinian archaeology”), who pioneered the excavation of Tels and dating by pottery, and Kenyon, with the grid/balk method of excavating (known as the “Wheeler-Kenyon method”), which allowed stratified layers to be readily seen and understood in their context.

As technology and experience developed, many of the original mistakes were corrected; many of the mislabeled items were refit into their proper historical and biblical settings. Today, archaeology is a refined science. Archaeologists have at their disposal several proven techniques for accurate dating as well as precise excavation methods. Technology has provided all sorts of new procedures and practices, from wet-sifting to noninvasive scanning techniques.

Faith Lost

But while the science has progressed, there has been no such corresponding progression of confidence in the biblical account. Instead of combining the new techniques and technology with the biblical record, the general archaeological community has grown increasingly secular.

The great paradox of it all is that even as the field has become more anti-Bible, archaeologists have over the last century uncovered literally thousands of biblically related discoveries. Ironically, as time progresses, more and more artifacts are being found corroborating biblical history and actually contravening Darwinism and other long-held evolutionary views. aiba will continue to explore many of these incredible finds in detail.

Today the sad reality is that 150 years of secular evolutionary theory and theological renunciation has resulted in the widespread and institutionalized rebuke of the Bible, even as a historical source. Sadly, this is the typical state of mind of many archaeologists—even “biblical” archaeologists—in Israel and the rest of the world. There is, of course, a spectrum. Some archaeologists are open to consultation with the biblical record. A rare few consider it a credible source. Most, however, are to some degree hostile.

A Scholarly View

Due to this innate prejudice, many scholars today—even many biblical scholars and archaeologists—spend their careers attempting to disprove the Bible. It is common to hear respected scholars totally dismiss the Bible as a historical source. Consider, for example, this remark from biblical scholar Niels Peter Lemche: “We know that the Old Testament scarcely contains historical sources about Israel’s past …. [It] is simply an invented history with only a few referents [sic] to things that really happened or existed.”

Remarks like this are destructive. People naturally look to, respect and believe the “experts.” Most people do not have either the time or the specialist education to understand many of the complex excavation reports or dry academic papers—so they naturally rely on scholarly interpretation. Most people are not aware that there is often prodigious disagreement among these scholars, or that they have a tangible anti-Bible bias. (It goes without saying that Lemche’s remark is utterly contrary to archaeological evidence.)

In BC: The Archaeology of the Bible Lands, Magnus Magnusson wrote the following about the purpose of biblical archaeology: “The scene of scholarly debate has long been curtained off from the general public, with the excuse that the layman cannot understand. One may believe, as I do, that the specialist has underestimated his wider public, or has found himself incapable of presenting involved arguments to a general audience.”

This observation by Magnusson gets to the heart of why the field of biblical archaeology was originally established: to benefit the general public.

Actually, in the early 20th century, the Palestine Exploration Fund confronted—and rectified—the issue of inwardly focused, elitist scholarship. The organization in the early 1900s was being criticized for becoming too dry and too academic. It had gotten out of touch with the general public and had become intellectually arrogant and self-serving. The charge was that “however interesting the researches of the society may be to geographers and anthropologists, the plain Bible student, who is not concerned with abstract science, derives little or no benefit from them; and they do not help him to an explanation of any difficulties that may meet him in his reading.”

Robert Macalister, an Irish-born archaeologist and the director of excavations for the pef from 1901–1909, took this critique to heart and subsequently published a popular account of his excavations. He also published interesting, readable seasonal reports for the general public.

The Mazar Touch

While Macalister was producing his pef reports, a child was born in Poland who would grow up to be a founding father of Israeli archaeology, as well as the affectionately termed “dean of biblical archaeologists.” His name was Benjamin Maisler (he changed his surname to Mazar after he immigrated to Mandatory Palestine in 1929). In 1949, less than one year after Israel became a nation, Mazar was granted Israel’s first excavation license.

Benjamin Mazar was best known for his archaeological method. According to his nephew Amihai Mazar (another eminent archaeologist), Professor Mazar’s “main contribution was the synthesis of biblical and archaeological research …. He laid the foundations for integrative research that combined the study of archaeology, the Bible, ancient Near Eastern sources and historical geography.” Mazar was both president of Hebrew University and professor of Biblical History and Archaeology, and he was largely responsible for Hebrew University becoming the world leader in the field of biblical archaeology.

Prof. Benjamin Mazar remains one of Israel’s most famous and well-respected archaeologists. And while his pioneering work in biblical archaeology has today become unfashionable, one archaeologist in particular holds fast to his legacy—his granddaughter, Dr. Eilat Mazar. Like her grandfather, Dr. Mazar deeply values both the scientific method and the Hebrew Bible. Dr. Mazar has said, multiple times, “I work with the Bible in one hand and the tools of excavation in the other, and I try to consider everything.”

The fruits of her approach speak for themselves. Dr. Mazar is responsible for some of the greatest archaeological discoveries made in Israel, including the palace of King David, a gigantic Solomonic-era gatehouse and tower, an enormous Solomonic wall, and a portion of Nehemiah’s wall. There have also been many smaller finds, such as the personal seal stamps (bullae) of King Hezekiah and Isaiah the prophet; bullae belonging to the two biblical princes and enemies of Jeremiah, Jehucal and Gedaliah; the oldest piece of writing ever found in Jerusalem; the earliest alphabetical inscription found in Jerusalem (and possibly in all Israel); the largest vessels ever discovered in Jerusalem; possibly the largest Year 4 Revolt coin hoard ever discovered; and one of the three largest gold hoards ever discovered in Israel.

Mazar is an anomaly in Israel’s archaeological community, and a lightning rod for debate. Despite her staunch commitment to the scientific method and strict adherence to proper archaeological practices, Dr. Mazar is often viewed with great cynicism. Why?

Hershel Shanks, former editor of Biblical Archaeology Review magazine, explained: “No one would question her professional competence as an archaeologist. Her chief sin, however, is that she is interested in what archaeology can tell us about the Bible … making a reasonable judgment about archaeological evidence as it relates to the Bible. In some scholarly circles this is considered unscholarly. If the judgment she made related to something other than the Bible, no one would give it a second thought. Only a finding related to the Bible brings such obloquy down on the head of a leading archaeologist.”

Like her grandfather before her, Dr. Mazar actually considers the biblical text when undertaking her archaeological work. Surprisingly, this makes her unique among her peers and somewhat controversial. Meanwhile, Mazar’s detractors simply cannot understand why, in the land of the Hebrew Bible, Dr. Mazar keeps making astounding, biblically significant discoveries. The answer is obvious: Dr. Mazar is willing to seriously consult the Bible.

The Bible, as most people realize, provides a historical account of ancient Israel. Doesn’t it make sense that someone wanting to understand this past would look in that text for guidance?

Archaeologists and historians studying ancient Greece consult Herodotus and Homer. Archaeologists and historians studying ancient Egypt consult Manetho. Why wouldn’t an archaeologist or historian studying Israel consult the Hebrew Bible?

Instead of considering this ancient text, many scholars today overlook and ignore it. The tragic reality, as Moorey explained in A Century of Biblical Archaeology, is that in the “last 50 years [up to the 1990 publication date], archaeologists … have come to regard biblical archaeology as a byword for prejudice and unscientific procedures. In this respect it has all too often been assessed rather more than is just ….

There has been, as there will continue to be, good, bad and indifferent research and scholarship in biblical archaeology, as in any academic discipline; but it will remain unusually vulnerable to prejudice.”

The prejudice of academics certainly doesn’t affect the Hebrew Bible—a text that has remained fixed for over 2,000 years. It is instead the skeptics who have to keep moving the goalposts and adjusting their theories as more discoveries are made. Some downplay those discoveries where they can (such as the infamous Tel Dan inscription, containing inscriptional proof of King David)—all the while desperately holding out hope for the discovery of something, anything that might disprove the biblical account. It’s getting to the point that cynics are having to not only reject the Bible to hold on to many of their opinions—they’re also having to reject science.

‘Behold Your God’

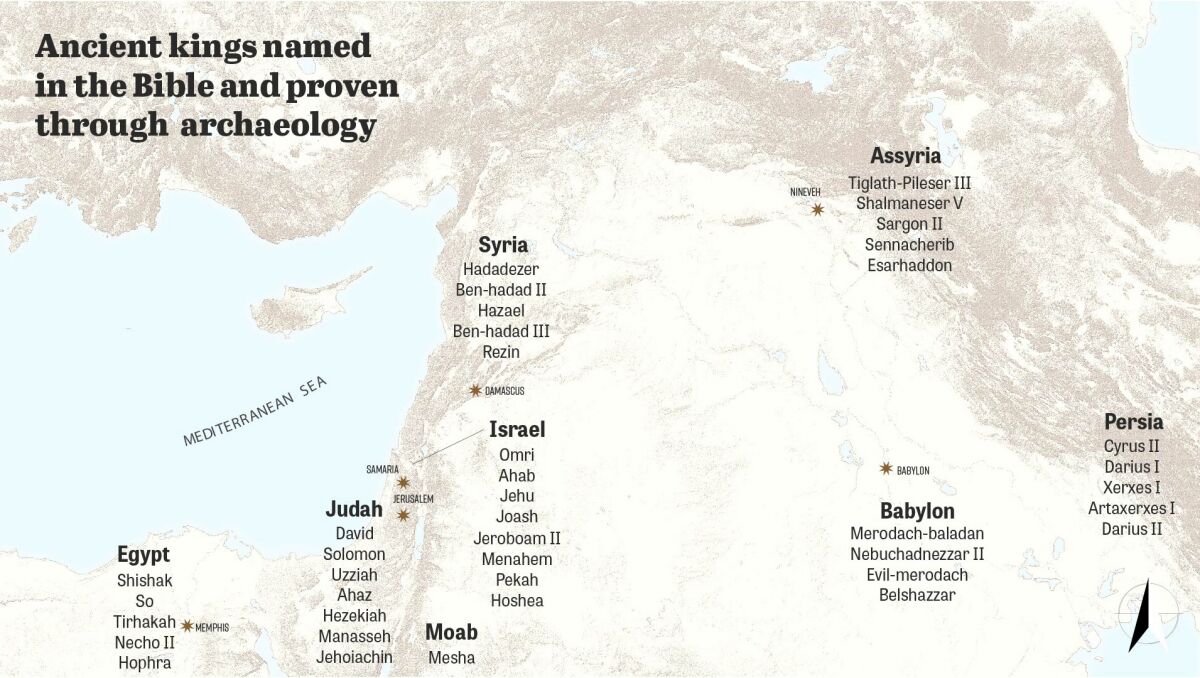

And so here we are now: 2019. Currently, nearly 60 individuals from the Hebrew Bible have been independently proved through archaeology, including kings, pharaohs, princes, governors, officers and priests. Biblical archaeology has confirmed dozens of biblical cities, as well as the biblical events that happened within them. It has verified everything from biblical civilizations and major conflicts to minor skirmishes, cultural customs, dietary details, clothing items, architectural elements, and even common sayings.

The plethora of discoveries attests to the accuracy of the biblical text. How can we then turn around and neuter our archaeology of it? How can we afford to cast aside such treasured, important cultural history—to excise it from the classrooms, the excavation fields? Of course, the responsible archaeologist does not read into his finds any more than what is there and what is logical. As Dr. Mazar says, we must let the stones speak.

And speak they do! “For the stone shall cry out of the wall …” (Habakkuk 2:11). Across Israel, the stones of archaeological excavations are crying out of the walls, in harmony with the biblical account—from Jerusalem to Samaria, Dan to Beersheba. And those stones carry a message that needs to be taken beyond mere academic circles. They show the plethora of facts behind a text that has been, for 2,000-plus years, simply faith for untold millions. Their message transcends the physical field of science and scholarship, doubts and endless questions, tedium and diffidence.

The many “regular Joes,” the volunteers that work on excavations in the Holy Land, hear it. It is a sort of supernatural, spiritual message coursing through the earth, through the walls, through the artifacts. A message that the Prophet Isaiah encapsulated in Isaiah 40:9: “O thou that tellest good tidings to Zion, Get thee up into the high mountain; O thou that tellest good tidings to Jerusalem, Lift up thy voice with strength; Lift it up, be not afraid; Say unto the cities of Judah: ‘Behold, your God!’”