New archaeological (or rather, archaeozoological) research has made headlines around the world this week, showing that the ancient Jews during biblical times were comparatively frequently eating non-kosher fish—a lot more frequently, that is, than they ate non-kosher pigs. Does this mean biblical laws about non-kosher fish were added after the biblical period—as an afterthought?

The authors of the study, Dr. Yonatan Adler of Ariel University and Prof. Omri Lernau of the University of Haifa, presented their findings in the latest Journal of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University. They studied 56 assemblages of fish bones, spanning from 1550 b.c.e. to 640 c.e., finding that the “consumption of scaleless fish—especially catfish—was not uncommon at Judean sites throughout the Iron Age and Persian periods.” When the unclean fish did become notably uncommon was from the Roman period forward. This has led to the suggestion that the parts of the Torah describing kosher fish (Leviticus 11:9-12 and Deuteronomy 14:9-10) were composed very late, during the Hellenistic-Roman period—either that, or it was from this period that the laws about kosher fish became known about and widespread. Adler commented on his research: “We do not have any evidence that the Judean masses, that your regular everyday Judean you would have met on the street of Jerusalem, prior to the middle of the second century b.c.e. had any knowledge of the Torah and or that he observed the rules of the Torah.”

As Haaretz journalist Ariel David put it: “The ancient Israelites apparently feasted on catfish, sharks and other taboo catch during the entire First Temple period, including the days of the mythical kingdom of David and Solomon, and well into the Second Temple era. Only from beginning of the Roman period, in the first century b.c.e., is there clear archaeological evidence that the Jews were eschewing prohibited fish, concludes the study published Tuesday.”

The news has led to some rather furious back-and-forth comments on articles, debating the conclusions. Do the findings point only to a late composition, or late knowledge, of these Torah laws?

One of the cited areas of research in the study was Jerusalem. This is an extremely important site for the study, for obvious reasons: As capital city, it was the nerve-center of laws, edicts, core religion and royal example to the nation.

Two years ago, we produced an article about our archaeozoological findings in Jerusalem (in excavations directed by the late Dr. Eilat Mazar), relating to clean and unclean fish. These remains were originally studied by Lernau and published by Mazar in 2015. His summary, especially as it relates to the above-cited “kingdom of David and Solomon,” might come as a surprise in light of the current discourse. Excerpted below is our article—with sections pertinent to the current research bolded, and comments added in [brackets]—followed by an updated conclusion about the latest findings: How they actually fit strikingly well with the biblical account, as well as the practical observance of kosher laws.

The Mazar Excavations

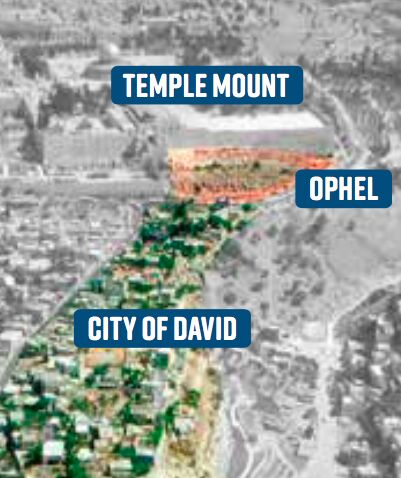

Dr. Eilat Mazar has now published the results of her 2005–2008 City of David excavations and 2009–2013 Ophel excavations in a series of thorough academic volumes. In this [2019] article, we’ll look at the results of the faunal analysis, completed by archaeozoologists Omri Lernau, Liora Kolska Horowitz, Karin Tamar and Guy Bar-Oz. The faunal remains thus far published in the current volumes come from two specific areas that we will describe in this article:

- The City of David, Area G (2007–08): Material dating from Iron iib to the Persian period (circa late seventh to fifth centuries b.c.e.)

- The Ophel, Area A (2009): Material dating to Iron iib (ninth to seventh centuries b.c.e.)

These are two comparatively small excavation areas (especially Ophel Area A)—yet from these assemblages alone, the results are fascinating.

Seafood

We begin with the fish remains. A large number were discovered within both excavation areas. The majority of remains by far were from porgies—a small, kosher saltwater fish. Other examples included mullets, cichlids and groupers.

Notable, though, were the high number of catfish remains discovered—from the Ophel, 15 percent of all fish remains; and the City of David, 28 percent. Curiously, some remains of rays were also found in both locations—a dietary oddity sourced either from the Mediterranean or the Red Sea.

[These numbers are in fact much higher than the across-the-board percentages highlighted by Lernau and Adler—their Iron ii assemblages averaged out to 13 percent non-kosher fish.]

The archaeozoologists note that fish would generally have had to be transported after it had been dried, because of the long journey from the sea and freshwater sources to Jerusalem. The Bible mentions a specific gate of the city apparently for just such trade: the “fish gate,” described in 2 Chronicles 33:14, Nehemiah 3:3 and Zephaniah 1:10.

Regarding the non-kosher fish: Taken as a whole, they are still in the minority of the consumed assemblage of fish. But it is interesting to note that based on the remains found in different strata in the City of David, the relative percentage of catfish consumed dramatically spiked just before the fall of Jerusalem to the Babylonians. The Bible describes this as a rebellious time in which, among other things, the inhabitants were consuming unclean food—a time that culminated in the destruction of the city. More on this further down.

This pre-destruction “spike” is interesting to note because it surpasses the percentages of catfish remains found in other excavations of this time period around Israel, and even within different strata of Jerusalem. Omri Lernau speculates that this is the result of a specific group of people inhabiting the large building above the Area G dump, which he calls “not representational of the general inhabitants of the city.”

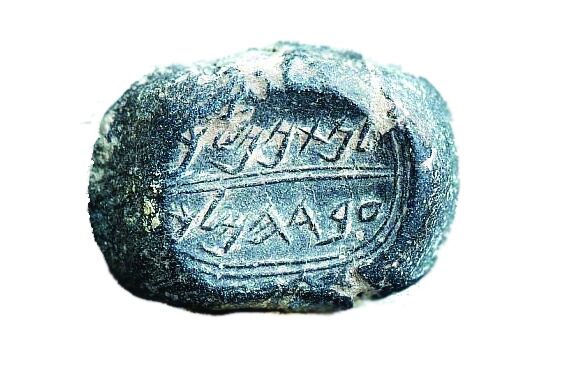

Dr. Mazar has identified this building as King David’s palace—a building whose use continued into this period, just before the Babylonian destruction, as a royal administration building (Jeremiah 36:12; Nehemiah 12:37). The royal seals of two biblical princes of this period, Jehucal and Gedaliah, were found here—these two, and their fellow cronies, attempted to have the Prophet Jeremiah put to death. The prophet writes about these particularly loathsome, rebellious individuals who would likely have occupied this building their seals were found in (Jeremiah 38). It seems they had a taste for catfish.

Lernau summarizes the following in Mazar’s City of David 2005–2008 publication, comparing her faunal material to other, earlier faunal remains found at an adjacent Jerusalem “pool” location (emphasis added):

Catfish, as mentioned, were deemed non-kosher by Judaic laws in the Bible. Apparently, Iron iia Israelites in Jerusalem [the early, united kingdom period of David and Solomon], whose food remains were found in the “pool,” did in fact refrain from eating catfish, while the inhabitants of the later buildings above the dumps in Area G [Mazar’s assemblage described in this article] did not. The reason for the latter could be connected to a reduced adherence to biblical tradition or because the inhabitants belonged to a different ethnic group.

[The quote at the top of this article, then—“The ancient Israelites apparently feasted on catfish, sharks and other taboo catch during the entire First Temple period, including the days of the mythical kingdom of David and Solomon”—is a misrepresentation. And by applying the same logic of the current discourse, the biblical kosher fish laws were in place and being followed by or before 1000 b.c.e.]

Catfish remains continued to be consumed in the city on into the Persian period. This too is interesting to note, when paired up with an account of the parallel time period in Nehemiah 13:16. “There dwelt men of Tyre also therein, who brought in fish, and all manner of ware, and sold on the sabbath unto the children of Judah, and in Jerusalem.” Nehemiah proceeded to sharply rebuke the inhabitants, shutting out the traders from entering into the city on the Sabbath. Given the Jews were failing to keep the Sabbath, it is unsurprising that they would be buying unclean fish from the pagan Tyrians. The Persian-period fish remains found in the City of David may well constitute these very purchases described in Nehemiah.

[The Persian-period Jews, then, were doing far more than simply eating unclean fish, as the research shows. They were not keeping the Sabbath! But the existence of the Sabbath command, by this point, is well attested-to.]

Mammals

[This section is a little outside the scope of the current fish analysis, but it contains some important points.]

The majority of Iron Age ii mammal remains in both Area G and Area A belong to the expected creatures: sheep, goats, cattle. However, pig remains were also found.

Actually, pig remains are found across most Iron ii sites in Judah—but unlike the neighboring countries, the ratios are far smaller—around 2 percent of the faunal assemblage. The same overall percentage was discovered on Dr. Mazar’s 2009 Ophel excavation; although, the pig remains in one of the earth layers—the upper, latest layer—represented a high 10 percent of the total remains.

[This was particularly noted in Adler and Lernau’s current research, comparing what therefore appears to be a knowledge of and adherence to kosher laws when it comes to pigs, versus comparatively less knowledge or adherence to laws about fish. More about this in the conclusion.]

This consumption of pork fits well, again, with the biblical account. The generally extremely low percentages, when compared to the diets of Israel’s ancient neighbors, clearly attest to the existence of laws forbidding its consumption. However, there did remain individuals even within the royal city who consumed the forbidden animal. This makes sense, given the number of rebellious Judahite kings that ruled from Jerusalem’s Ophel. The 10 percent spike in pig consumption—based on the layer in which it was found—may well relate to the reign of King Manasseh, who presided over some of the most shocking abominations in Judah’s history (2 Kings 21). Regarding the consumption of pig (among other things), the Prophet Isaiah—who according to tradition was killed by Manasseh—delivered the following condemnation from God (Isaiah 65:2, 4; 66:17):

I have spread out My hands all the day unto a rebellious people … That eat swine’s flesh, and broth of abominable things is in their vessels …. They that sanctify themselves and purify themselves to go unto the gardens, behind one in the midst, eating swine’s flesh, and the detestable thing, and the mouse, shall be consumed together, saith the Lord.

It is, perhaps, fitting that the personal seal stamp of the Prophet Isaiah was found in the same earth-fill as these pig bones.

The City of David excavation of Area G did not reveal any pig remains. It did, however, uncover a variety of remains of various other creatures. The earliest remains from the Area G assemblage date to the very end of Iron iib—essentially, the last 50 years before the fall of Jerusalem in 586 b.c.e. While the majority of bones were from goat, sheep and cattle, various other animal remains from this period included donkey, dog, cat, hare, rat and mouse. Considering these remains related to the last desperate moments before the fall of Jerusalem, it is possible that they were consumed by the inhabitants. Famine was rife in the city during the two-year siege (2 Kings 25:2-3), to the point that the Bible describes mothers boiling and consuming their own children (Lamentations 4:9-10). This was the horrific end that had been prophesied by Isaiah—the result of idolatry, witchcraft and general rebellion—including the blatant rejection of God’s laws of clean and unclean foods.

[When I initially wrote this article, I presented the below subhead conclusion. An updated conclusion relating to the current research is beneath.]

Culinary Corroboration

Thus we see that not only do archaeological finds such as inscriptions and structures corroborate the biblical account—so too do the plain old, “boring” bone fragments.

And they are important for another reason. The typical minimalist view is that the Torah—the first five books of the Bible—was forged by late writers claiming to represent the hand of Moses. The standard jedp hypothesis claims that parts of the Torah were variously written some 1,000 years later than “Moses” by a “J” Jahwist writer, an “E” Elohist writer, a “D” Deuteronomist writer, and a “P” Priestly writer. According to the theorized divisions, the clean and unclean laws of Leviticus 11 were written by the “P” writer circa 450 b.c.e., and those of Deuteronomy 14 were written circa 600 b.c.e.

[It is interesting that the current research has led to the suggestion of possibly adding an even later dimension to this—“fish laws” as being an add-on by some three-to-five centuries later.]

But with the faunal remains uncovered in Jerusalem and at sites all around Israel, we see the results of “clean” and “unclean” laws in place nearly 1,000 years before! Sure, there are small percentages of unclean remains—but the Bible itself attests to these. (For more evidence for the traditional dating of the Torah, see our article on the subject here.) The archaeology is clear—there was a stark distinction between ancient Israel and its neighbors, from the period relating to Israel’s conquest of Canaan (circa 1400 b.c.e.) onward.

A distinction that remains to this day. Yet still, as with ancient Israel, the pork and catfish continue to be served up.

[As a side: More non-kosher fish is eaten now in Israel than at any point in the nation’s history. Does that refute the early nature of the biblical “fish laws”?]

Conclusions Relating to the Current Research

The 2019 article, then, demonstrated that some form of kosher laws were in place during the biblical period—and further, as per Lernau’s suggestion in Chapter 16 of The Summit of the City of David Excavations 2005–2008: Final Reports Vol. 1, indicating that these fish laws were being adhered to in some form as far back as the the Iron iia period—the 10th century b.c.e. (the time of David and Solomon).

The recent tau article does bring up a good question: Why was pork so rarely eaten compared to unclean fish? If ancient Judahites and Israelites were abstaining from non-kosher pork, why weren’t they abstaining as frequently from non-kosher fish? A natural conclusion is that either these Torah laws weren’t in place, or the population didn’t know about them.

In one respect, this fits perfectly with a nugget in the Bible.

2 Chronicles 34 describes that during the seventh-century b.c.e. reign of the righteous King Josiah, a copy of the Torah was found. “And it came to pass, when the king had heard the words of the Law, that he rent his clothes” (verse 19). This was a king who, to this point in the story, had been considered righteous. Yet here, upon the rediscovery of this important book, he realized how many laws continued to have been broken unawares. “‘Go ye, inquire of the Lord for me, and for them that are left in Israel and in Judah, concerning the words of the book that is found; for great is the wrath of the Lord that is poured out upon us, because our fathers have not kept the word of the Lord, to do according unto all that is written in this book’” (verse 21).

Evidently, during this period of righteous reform, some laws were being kept—but many were not, thanks to the damage and suppression done by numerous previous pagan kings (about half of all the kings in Judah’s history—and all the kings in the northern kingdom of Israel. Even during the reigns of righteous kings, the Bible highlights that the population did not entirely follow suit). This certainly fits alongside the evidence of a lack of detailed observance of the specific kosher fish laws, particularly during this later contemporary Iron iib period (as opposed to the earlier Iron iia, Davidic Jerusalem. David, remember, “delight[ed] in the law of the Lord,” “meditat[ing] on it day and night”—Psalm 1:2, etc.). Lernau’s statement attests to this. All that said, though: Overall, the vast majority of fish consumed were kosher (87 percent).

To this point of widely known laws: Even today, a common assumption is You’re a Jew, you don’t eat pork—less so, you don’t eat fish without fins and scales. (Perhaps “you don’t eat shellfish” would be the most often-heard generalization about seafood.) As Ariel David put it in his article, the “even more famous taboo on eating pig.” It’s a simple example, but the forbidding of pork to this day is surely the most commonly associated dietary law. It would only make sense that during the above-mentioned biblical period, during centuries of suppression—at worst paganism, and at best a lack of understanding about certain intricate laws contained in the Torah—pork would have been the food item more readily refrained from than specific types of fish.

This all goes hand-in-glove with another simple element. On a personal level: I try to adhere to the clean-and-unclean laws of the Bible. But having grown up and lived in other countries, I can almost guarantee that I’ve accidentally eaten more unclean fish than pork. One point of trouble is that the flesh of clean and unclean fish is almost impossible to differentiate (especially from less-than-honest sellers). Pork, on the other hand, is much more readily discernible from other meats.

Looking at it from another angle again: One has to deliberately choose and commit long-term to farming pigs. Fishing, however, is immediate and indiscriminate. You catch what you catch. This would be fine if the nation’s fishmongers were religious Israelites (a matter of throwing back unclean fish)—but the Bible itself tells us that they were not. Fish was imported from foreign fishermen among the sea-going Phoenicians, who certainly would not have cared for “minutiae” in Jewish law, in getting rid of plentiful unclean fish such as catfish (Nehemiah 13:16; also note Jonah 1 and 1 Kings 9:26-27). The drying and delivery of the flesh inland would only further affect the appearance of the fish (not to mention any underhand methods by the foreign fishermen in making their catch appear more desirable—or “kosher”—to their buyers). As noted by Adler and Lernau, the most defining, barbel-lined heads of catfish are heavy and contain little meat, so they would be discarded of at the fishing grounds.

Yet given all that—frequent national paganism, suppression of laws, foreign deliveries, difficult-to-determine flesh, an abundance of especially catfish in the region (not to mention the natural limitations of 1,500-to-3,500-year-old, incredibly fragmentary fish assemblages)—what strikes me as remarkable is that as a whole, the ancient Jews only appear to have overall consumed an average of 13 percent unclean fish. To me, this indicates that not only were they aware of kosher fish laws—but their foreign fish merchants, to a general degree, were as well!

The data presented in the current research does not refute an early authorship of the Torah—but together with Lernau’s summary of Dr. Eilat Mazar’s discoveries from ancient Jerusalem, it fits well with the early biblical account of when the Torah laws were written, a population who often rejected them, and how they fell out of detailed observance. In many ways, it’s a story that remains the same to this day. To quote King Solomon: “there is nothing new under the sun” (Ecclesiastes 1:9).