Where did the Israelites cross the Red Sea?

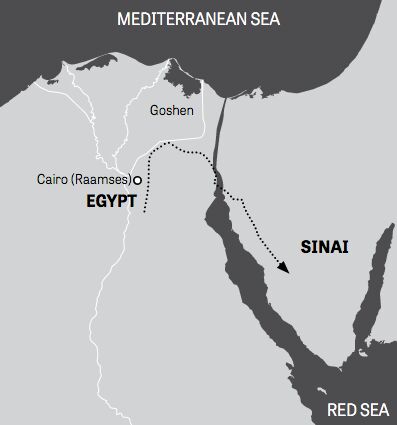

Strangely enough, it is a question that for Bible literalists hasn’t long been debated. The standard wisdom was that it took place at the northern end of the Gulf of Suez, heading into the Sinai Peninsula, with a Mount Sinai at the bottom end of the peninsula. Indeed, this was the crossing point shown in Cecil B. DeMille’s famous (and famously well-researched) 1956 film The Ten Commandments.

But over the last several decades, there has been significant debate surrounding two other options: a “Bitter Lakes” option (crossing one of the shallow inland lakes much further north of the Gulf of Suez); or notably a Gulf of Aqaba crossing, on the far side of the Sinai Peninsula—leading into what is today Saudi Arabia.

Last year, the Thinking Man film company that produces the Patterns of Evidence documentaries released a two-part film titled The Red Sea Miracle addressing this very question.

The Patterns of Evidence documentaries are well-produced, thought-provoking films examining the historical evidence for some of the greatest stories in the Bible—namely, the slavery of the Israelites, the existence of Moses, the Exodus, and the parting of the Red Sea. The documentaries bring together different minds offering different views and opinions on the historicity, chronology, and location of various events.

Such was the case with the two-part Red Sea Miracle. But surprisingly, only two general crossing options were presented: a northern Bitter Lakes crossing, termed the “Egyptian approach”—this as a more strictly “scientific,” naturalistic approach; and a Gulf of Aqaba crossing, termed the “Hebrew approach”—this as a more literalistic “biblical” approach.

Unfortunately, in the four hours of screentime, barely a minute was given to briefly mention and dismiss the crossing point that perhaps most naturally comes to mind: the Gulf of Suez.

The debate about where the Red Sea crossing took place has become a hot topic. Which is the biblically accurate location? For this article, we’ll leave out the more minimalist Bitter Lakes theory (as it is, in several points, contrary to the biblical account, and primarily exists to provide explanations for the miraculous events through natural phenomena—Red Sea Miracle did a thorough job in covering this theory). We’ll instead compare the Gulf of Aqaba crossing theory with the Gulf of Suez, to see which best fits the literal biblical account.

Where Was Mount Sinai?

At the core of this debate—indeed, an impetus for certain researchers to consider a more distant Gulf of Aqaba crossing—is the identification of Mount Sinai, the location where Moses was first called by God, and the mountain before which the Israelites later encamped and received the Ten Commandments. This article is not intended to establish the exact identity of the mountain (see the following for more on this subject). But we will need to spend a little time on it based on how the geographic area relates to the sea crossing, which would naturally have taken place west of it.

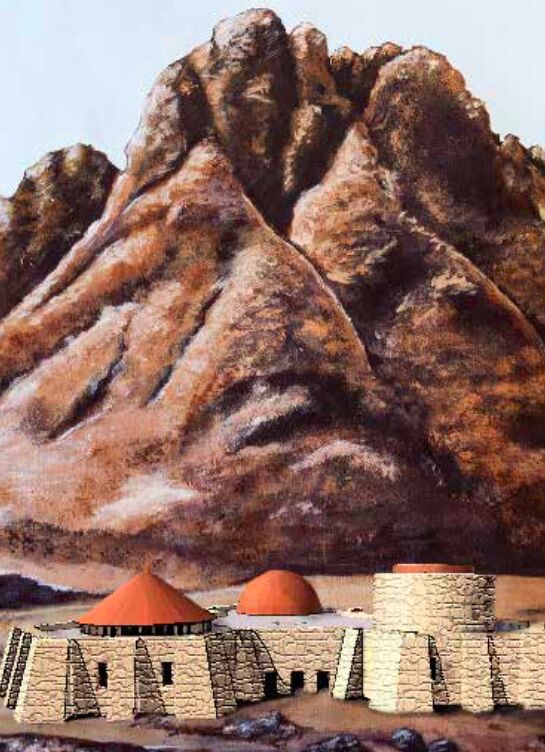

The long-standing traditional identification of Mount Sinai has been Jabal Musa, “Moses Mountain,” located in the southern part of the Sinai Peninsula. Unfortunately, we cannot look to the name Sinai Peninsula for proof of where Mount Sinai was, given that it is an apparently more modern term given based on the traditional identification of Jabal Musa as Mount Sinai. (*Update: New research published in 2023 is challenging this assumption, asserting that the southern Sinai was anciently referred to by this equivalent term—see here for more detail.) Jabal Musa certainly became well-known and established as the site of Mount Sinai through the early Christian-Byzantine period (fourth century c.e. onwards), but certain earlier evidence also points to this general southern Sinai territory as a region of pilgrimage and religious veneration for the Nabataeans as early as the third century b.c.e.—as shown by various inscriptions in the region, and the remains of Nabataean sanctuary/temple architecture unearthed in the 1970s and ’80s (see, for example, research articles here and here; the Arab Nabataeans likewise held Moses in esteem).

A Mount Sinai in the Sinai Peninsula means that the sea crossing must have taken place to the west—i.e. the Gulf of Suez. The towering mountain and surrounding ranges certainly make for an impressive site. But over the past several decades, an increasingly popular alternative mountain has been posited: Jabal al-Lawz.

Known as the “almond mountain,” this site is located just east of the Gulf of Aqaba in modern-day Saudi Arabia. There’s some debate surrounding the naming of this mountain and the nearby Jabal Maqla (“burnt mountain,” see illustration on right for the locations of these and other posited “Mount Sinais”). The Bible uses two names in the context of this mountain of God: Horeb and Sinai. in the case of the Aqaba-crossing theory (depending on the proponent), Maqla represents one, and al-Lawz the other; two peaks of the same range. Specifically, the blackened tip of Jabal Maqla is seen as the place where God descended in “fire” to deliver the 10 Commandments (Exodus 19:18; see the short drone footage of the black-topped mountain below).

We read from certain classical accounts that Mount Sinai was the tallest in the vicinity (hence the particular selection of these two respective regions, in either southern Sinai or northwestern Saudi Arabia)—note the first century Josephus’s description of the mountain as the “highest of all the mountains thereabout” (Antiquities of the Jews, 2.12.1), or the first century Philo’s description of it as the “loftiest and most sacred mountain in that district” (On the Life of Moses, 2.14.70). But which is the right region—and thus which is the right gulf crossing corresponding to it?

Proponents for a Red Sea crossing at the Gulf of Aqaba highlight Paul’s statement in the New Testament, mentioning “mount Sinai in Arabia” (Galatians 4:25). Likewise, they point out a geographical association of Mount Sinai with the land of Midian (i.e. Exodus 2-3). Midian is traditionally located in modern-day northwest Saudi Arabia, and Jabal al-Lawz is located in the heart of a range of mountains known as the Midian Mountains. Distinct from the Sinai Peninsula, this is a range of volcanic mountains, which some proponents connect to the “smoke and fire” of God’s presence on Mount Sinai.

Additionally, Aqaba proponents argue that the Sinai Peninsula was part of Egypt: Given that Moses fled to Midian from Egypt, and that the sea crossing took place to remove the Israelites from Egypt, the Sinai Peninsula therefore could not have been the location of Mount Sinai, and the sea crossing could not have happened at the Gulf of Suez—the sea crossing must have taken place on the other side of the peninsula, the Gulf of Aqaba. Furthermore, it is pointed out that the near-impassable mountain ranges on the western shore of the Gulf of Aqaba hearken dramatically to the biblical account of Israel being “trapped” before the Red Sea.

The evidence seems compelling: Jabal al-Lawz/Maqla must be Mount Sinai, and the Gulf of Aqaba must have been the location of the Red Sea crossing.

But it is not quite that simple.

In Arabia?

It is natural today to look at the Sinai Peninsula and consider it “Egyptian” territory, and northwestern Saudi Arabia as the start of the “Arabian” territory. But historically, that hasn’t always been the case. In fact, it’s more of an historical aberration.

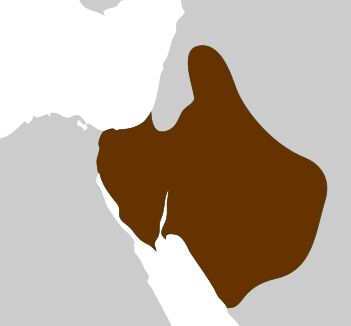

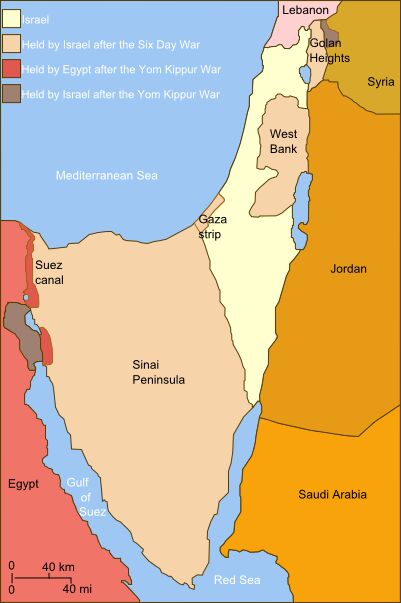

When Paul mentioned Mount Sinai “in Arabia,” the Sinai Peninsula was itself geographically considered part of wider Arabia. The Romans called this Sinai province Arabia Petraea (see map, right)—a territory in large part made up of the Sinai Peninsula, and ruled by them from the start of the second century c.e. to the sixth.

And classical historians in the centuries leading up to Paul were likewise labeling the Sinai Peninsula as part of Arabia, not associated with Egypt in the west. One reason for this is its parallel geography to the rest of Arabia, as well as it being home to the same nomadic tribes of people dwelling within. The Romans conquered their Sinai “Arabia” territory from the Arab Nabateans (left), whose kingdom spanned from the third century b.c.e. to c.e. 106. The Nabateans took it over from the earlier Arab Qedarites (below, right).

Right up until modern times, the Sinai Peninsula has been named the “Peninsula of the Arabs … one of the earliest seats of the Great Semitic race” (Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography, William Smith, 1854; emphasis added throughout). Smith even described the Sinai Peninsula as “a region which no other people has ever disputed with them [the Arabs].”

In fact, in the third century b.c.e., the Jewish translators of the Bible into the Septuagint Greek (lxx) called the land of Goshen, where the majority of the Israelites dwelled during their time in Egypt, as “of Arabia” (Genesis 46:34; lxx). Thus, if Paul’s first century “in Arabia” statement means that Mount Sinai cannot have been in the Sinai Peninsula, then by that same logic these Israelites were not slaves in Egypt! Paul’s statement, then, in no way precludes a Mount Sinai in the Sinai Peninsula, and thus a crossing of the Gulf of Suez.

But there is a key biblical reason for this identification of Sinai (and even Goshen itself) with Arabia. In Genesis 15:18, God promises Abraham that his descendants (which include the Israelite and Arab peoples) would possess “this land, from the river of Egypt unto the great river, the River Euphrates [Mesopotamia].” What was the river of Egypt? It was, of course, the Nile. The Israelites were given land in Goshen, east of the Nile, by the pharaoh (Genesis 47:6). 1 Kings 8:65 reveals that King Solomon controlled this territory, from Syria all the way to the “river of Egypt” (kjv). Even in 1967, the Sinai Peninsula was miraculously returned to Israeli control, before it was turned back over to the Egyptians some years later. Yet even the Muslim-dominated Egypt of today is distinct from the Hamitic/Cushite Egyptians of old (Genesis 10:6, Ezekiel 30:13). Again, as affirmed by Smith, the Sinai Peninsula is a territory “which no other people has ever disputed,” that of the descendants of Abraham.

And to this day, it is the Gulf of Suez on the western edge of the Sinai that is the modern border separating the continents of Africa and Asia. The Sinai Peninsula categorized, again, with the Arabian side—not Egypt.

Paul’s reference to Mount Sinai “in Arabia,” then, would only be expected to relate to the Sinai Peninsula—it by no means excludes it. And one largely overlooked part of Paul’s statement is that he symbolically refers to Mount Sinai as Hagar, Abraham’s concubine and mother of the Ishmaelites. “The first woman, Hagar, represents Mount Sinai …” (Galatians 4:24; New Living Translation). Hagar was an Egyptian (Genesis 16:1). This at face value could conceivably lend to a location closer to Egypt, yet still within Arabian territory.

The first-century Egyptian writer Apion gets even more specific, stating that Mount Sinai was “between Egypt and Arabia” (as quoted by the first century c.e. Jewish historian Josephus in Against Apion, 2.2). This best fits the peninsula—and thus a sea crossing west of it, at the Gulf of Suez.

In Midian?

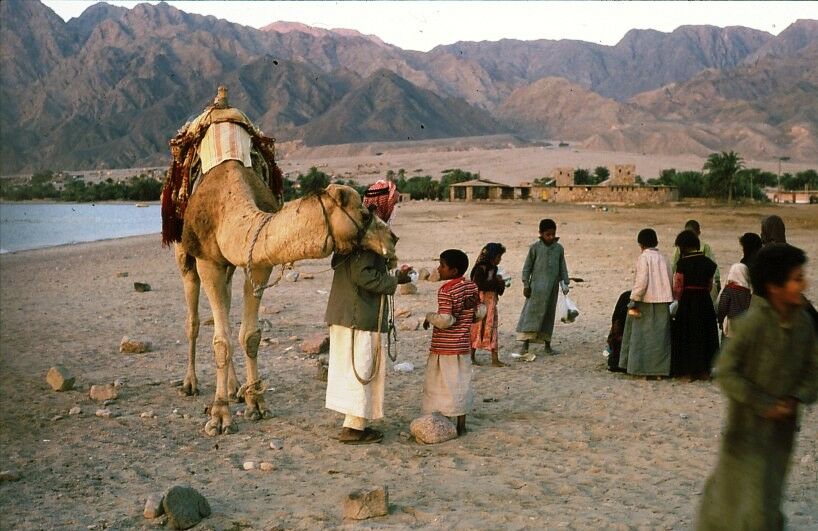

This is one of the biggest points made for Jabal al-Lawz: the association of the biblical mountain with Midian. After all, Moses fled from Egypt to the “land of Midian” (Exodus 2:15), and it was while shepherding the flock of his “priest of Midian” father-in-law, Jethro, that he was called by God from the mountain. The territory of Midian is often identified as directly south of Israel, southeast of the ancient land of Edom, east of the Gulf of Aqaba. As stated on Patterns of Evidence, “archaeologists and scholars know where this ancient land is, and it is located in the northwest corner of what is known today as Saudi Arabia.”

But the borders of the Land of Midian are very much not known. Borders are hard enough to establish for an ancient fixed civilization; the Midianites were (at best) a semi-nomadic one. Some sense of this is relayed in the name Midian, meaning “strife”—thus, Land of Strife, befitting a general desert nomadic territory. The Midianites themselves are an enigmatic civilization—very little related to their identity has been confirmed. There is a corpus of pottery known as “Midianite pottery” (properly known as Qurayyah Painted Ware), but it is largely dated to centuries after the Exodus. And though this pottery is indeed found in northwest Saudi Arabia, it is also found in the Sinai Peninsula, Israel, and Jordan. (See our article here for an interesting book of Judges connection with these discoveries.)

Besides this, though, the Bible itself nowhere says that Mount Sinai was in Midian. In describing Moses’s journey to Mount Sinai/Horeb, the Bible states that he went well out of his way. Moses “led the flock to the farthest end of the wilderness, and came to the mountain of God, unto Horeb” (Exodus 3:1). Other translations read “the backside of the desert” or “rear part of the wilderness.” The Hebrew word means a behind place, a hinder part, and can even be a directional term to refer to the “west” (as in the Revised Standard Version’s translation). This would fit with the location of the traditional Mount Sinai.

Further, Exodus 18 describes the freed Israelites encamped at the mountain of God, and being visited by a traveling Jethro, “priest of Midian.” At the end of the chapter’s account, Moses “let his father-in-law depart, and he went his way to his own country” (verse 27, rsv). A similar account of visitation while at Mount Sinai is given in Numbers 10—with an evident distinction between it and the land of Midian. Moses’ Midianite relative here is quoted saying: “‘I will not go [with you]; but I will depart [from here] to mine own land [Midian], and to my kindred [the Midianites].’ … And they set forward from the mount of the Lord” (verses 30-33). This points instead to a clear separation between Mount Sinai and the land of Midian.

The fourth-century c.e. Christian historian Eusebius is sometimes referenced to support a “Sinai in Midian” theory. He stated that Horeb is the “mountain of God in the Land of Madiam.” But like Apion, he stated even more specifically that “it lies … beyond Arabia in the desert,” and part of the “outlying countryside of Madiam” (see Eusebius’s Onomasticon, entry “Choreb”)—statements that fit best with the outlying Sinai Peninsula (and thus a Gulf of Suez crossing).

Midian certainly could have included part of the Sinai Peninsula—we just don’t know (and the Sinai Peninsula has been included in old cartography as part of “Midian”—for example, as on 17th century historian Thomas Fuller’s map “Desertum Paran”). But whether or not it did, that wouldn’t matter; Moses was a shepherd for 40 years. Given the desert “strife” conditions (mandating the nomadic nature of the Midianite people), he would have had to travel regularly to new grazing ground. He wouldn’t have remained singularly in a small zip code—the Bible tells us that. Recall the story of Jacob’s shepherd-sons, whom Joseph was sent to find: They were eventually found pasturing their sheep 100 kilometers (60 miles) away from where they were “supposed” to be, in the north of Canaan—and that, in a far more fertile region (Genesis 37:14-17; it is also worth noting that even in this northern location, Midianites are mentioned—see verses 28-36).

In the same vein, what could be considered modern “Midianites”—the Bedouin—do regularly migrate to the Sinai Peninsula “in search of water and pasturage” (Encyclopedia Britannica). “From the very nature of the country, the wandering tribes of N. Arabia, the children of the desert, always did, as they do to this day, roam over that triangular extension [the Sinai Peninsula] of their deserts” (Smith’s Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography, “Arabia”). The modern Tarabin Bedouin are the largest such group frequenting the Sinai Peninsula—they can also be found in Egypt, Israel, Jordan and Saudi Arabia.

In his 40 years of shepherding, is it outside the realm of possibility that Moses traveled to the Sinai Peninsula—as the Bible describes, the “remotest,” “backside,” “western” part of the wilderness?

Further: If the mountain really had to be embedded firmly inside Midianite territory in Saudi Arabia, where were all the Midianites? Why is there no mention of them during the Israelite sojourn (besides Moses’ journeying in-laws, Exodus 18 and Numbers 10), until just before the Israelites are about to cross into the Promised Land? (Numbers 22, 25, 31). And why, instead, are others mentioned around the territory of Mount Sinai—namely, the Amalekites? (Exodus 17).

Clearly, Mount Sinai was a territory somewhere remote to mainland Midian—again, fitting with the Sinai Peninsula, and again, fitting with a western, Gulf of Suez sea crossing to get to it.

In Egypt?

Another related point used by Aqaba proponents to disqualify the Sinai Peninsula, and to mandate an Israelite crossing of the Gulf of Aqaba, is that the Sinai was considered part of ancient Egypt. Thus, the fleeing Moses wouldn’t have stopped within the territory—and the Israelites would not have been truly “out of Egypt” unless they crossed the Red Sea on the far side, at Aqaba. We have covered this in part above, as it relates to Paul’s statement and the geopolitical situation at the time of the first millennium b.c.e. But what about during the mid-second millennium b.c.e.—the time of the Exodus? Was it a part of Egypt?

Egypt at this time did have a handful of “frontier” mining outposts in the central and upper Sinai Peninsula. But they were just that—frontier outposts—that had to be constantly guarded from marauding tribes. (Such outposts were also located in the vicinity of Edom and up into Canaan and Syria—where God intended to send the Israelites. Was this territory likewise “Egypt”?) Given the remote location, Egyptian texts reveal repeat skirmishes with marauders and indigenous Arabs—guards had to be posted to deal with the real threat.

And this Sinai Peninsula setting would fit well with the biblical account: It is immediately after their crossing of the Red Sea that the Israelites are set upon by marauding Amalekites (Exodus 17).

Even then, the Egyptian presence at these mines was not permanent, merely intermittent—only maintained when mining parties were sent out. As explained by John Bright in his book A History of Israel (pg. 125):

One need not suppose that a march in this direction [southern Sinai, toward Jabal Musa] would have brought the Hebrews into a collision with the Egyptian troops, for the Egyptians did not maintain a permanent garrison at the mines. Except at intermittent periods when mining parties were at work, the Hebrews could have passed unmolested. All things considered, therefore, a location for Sinai approximating the traditional one seems preferable. …

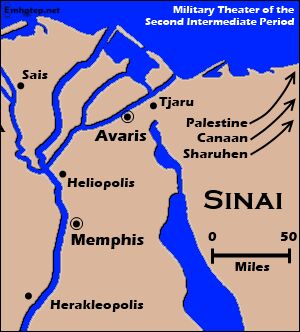

Further, the peninsula was also known as a place of banishment for Egyptian criminals. This could hardly be the case, if the Sinai Peninsula was “Egypt.” The fortress Tjaru, on the western edge of the Peninsula and north of the Gulf of Suez, has been discovered to be a place of banishment for criminals of the state (as relayed, for example, by the Great Edict of 14th century b.c.e. pharaoh Horemheb). Such would fit perfectly with a location from which Moses (and later the Israelites) would flee.

An earlier Patterns of Evidence documentary, Exodus, makes the convincing case for the Israelites as the “Hyksos” people that were expelled from Egypt in the mid-second millennium b.c.e. Pharaoh Ahmose i actually built a border of fortresses (part of which included Tjaru) along the western edge of the Sinai Peninsula in order to keep the Semites out of Egypt (below right). This clearly shows that the Sinai was not “Egypt.” Furthermore, this shows that it must have been along this very boundary—namely, south at the Gulf of Suez—that the Israelites must have crossed out of Egypt! (Note that Exodus 14:2 likewise mentions a fortress, Migdol, near to this sea crossing point.)

There were a handful of Egyptian fortresses dotted across the northernmost coastal strip of the Sinai Peninsula. These were to guard Egypt’s interests in the vital trade route known as the “Way of Horus” or “Way of the Philistines.” Again though, such Egyptian defenses were built all the way up into Syria.

Exodus 13:17 states that God did not want Israel to take this quickest, most direct “Way of the Philistines” route into Canaan. Why? Because it would mean the Israelites were “still in Egypt”? Quite the contrary: “[F]or God said, ‘Lest peradventure the people repent when they see war, and they return to Egypt’” (verse 17). God did not want Israel to see war along this fortified Sinai trade route and be moved to return to “Egypt”! The Bible therefore clearly recognizes such military outposts in the northern Sinai as being entirely separate and apart from Egypt proper.

All of this also aligns with Moses’s requests to Pharaoh to go “three days’ journey into the wilderness” to worship—far enough to be removed from Egyptian influence (e.g. Exodus 8:22-24; verses 25–27 in other translations). Was Moses actually meaning three days journey into another wilderness beyond the Sinai wilderness? Of course not—this must have referred to the Sinai Peninsula.

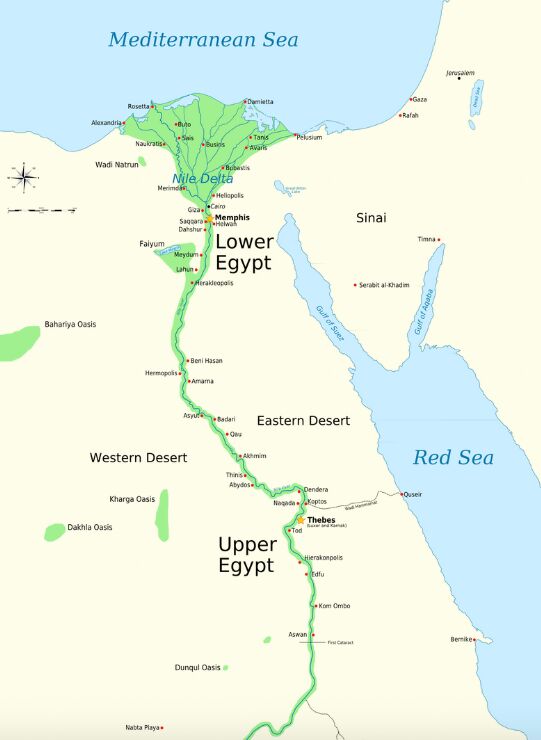

There is also the standard division of Egypt into “two lands” (also revealed in the Hebrew name for this country, Mizraim)—Upper Egypt in the south, and Lower Egypt in the north. Two lands of Egypt—not some form of “third” division, made up by the entirely separate Sinai Peninsula.

For more on this subject, see Egyptologist James K. Hoffmeier’s book Ancient Israel in Sinai. He highlights the veritable dearth of Egyptian reference to this wider geographical region of Sinai—further discounting its identification by Aqaba proponents as “Egypt,” and therefore the notion that the Israelites weren’t really “out of Egypt” until they were on the other side of the Sinai Peninsula. He also notes Egyptian inscriptional evidence directly referring to this Sinai territory as “foreign” land (page 37).

The Sinai Peninsula, therefore, cannot be regarded as “Egypt.”

Geography of Mount Sinai

As for the volcanic nature of certain of the mountains east of Aqaba, relating to the fire, smoke, quaking and sound described in Exodus 19: It is an interesting theory, but a rather naturalistic explanation for a miraculous event (especially given the Aqaba crossing theory is presented in opposition to “naturalistic” theories). Exodus 19:18 states that “mount Sinai was altogether on smoke, because the Lord descended upon it in fire ….” The smoke was because of God’s descent, not because of the mountain “erupting.” (A somewhat comparable event happened at Solomon’s dedicating of the temple—1 Kings 8—hardly a volcanic event.) Exodus 24:17 says that “the glory of the Lord was like devouring fire on the top of the mount.” The same mountain was also the site of the burning bush, where God spoke to Moses (Exodus 3). Was that also “volcanic activity”?

As for the black peak of Jabal Maqla: This is reportedly due to a makeup of black igneous volcanic rocks. It’s also worth pointing out that much of the surrounding general mountain range is also blackened (as shown below). The Bible doesn’t say anything about residue left from His presence on the mountain—but as far as the miracle of the burning bush, the biblical account specifies that no sign of fire was left behind (see also the same principle at play in Daniel 3). Moses’ person radiated brilliant light from his close proximity to God (Exodus 34). A case could be made for a similar effect on the summit, rather than a literal charring of the mountain.

Another point made for al-Lawz is that plenty of plains surround it for the Israelite camp, whereas the environs of Musa are quite rugged and inaccessible (though there are plains in this region to the north and south). But this fits with what Philo and Josephus recorded—the latter, that Mount Sinai was “very difficult to be ascended by men … because of the sharpness of its precipices also; nay, indeed, it cannot be looked at without pain of the eyes: and besides this, it was terrible and inaccessible” (Antiquities, 3.5.1.).

So Which Sea Was It?

Mountains and lands aside, can’t we tell where the Israelites crossed based on the name of the waterway?

The original meaning of the term used in the Bible, Yam Suph, has been hotly debated—primarily as meaning either “Sea of Reeds” or “End Sea.” We won’t get into the endless (and largely conclusion-less) debate here—and besides, both meanings could technically work for the general area of the Gulf of Suez.

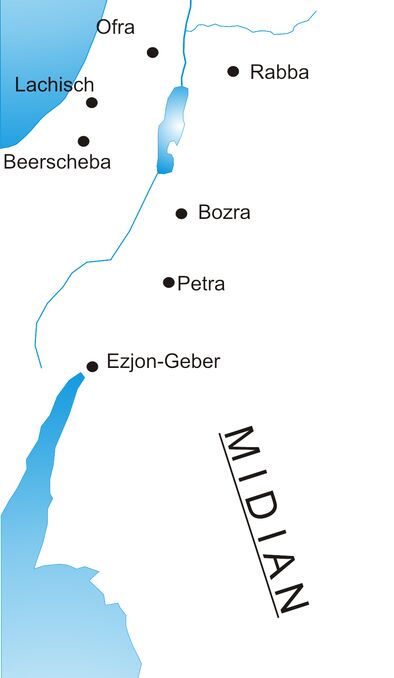

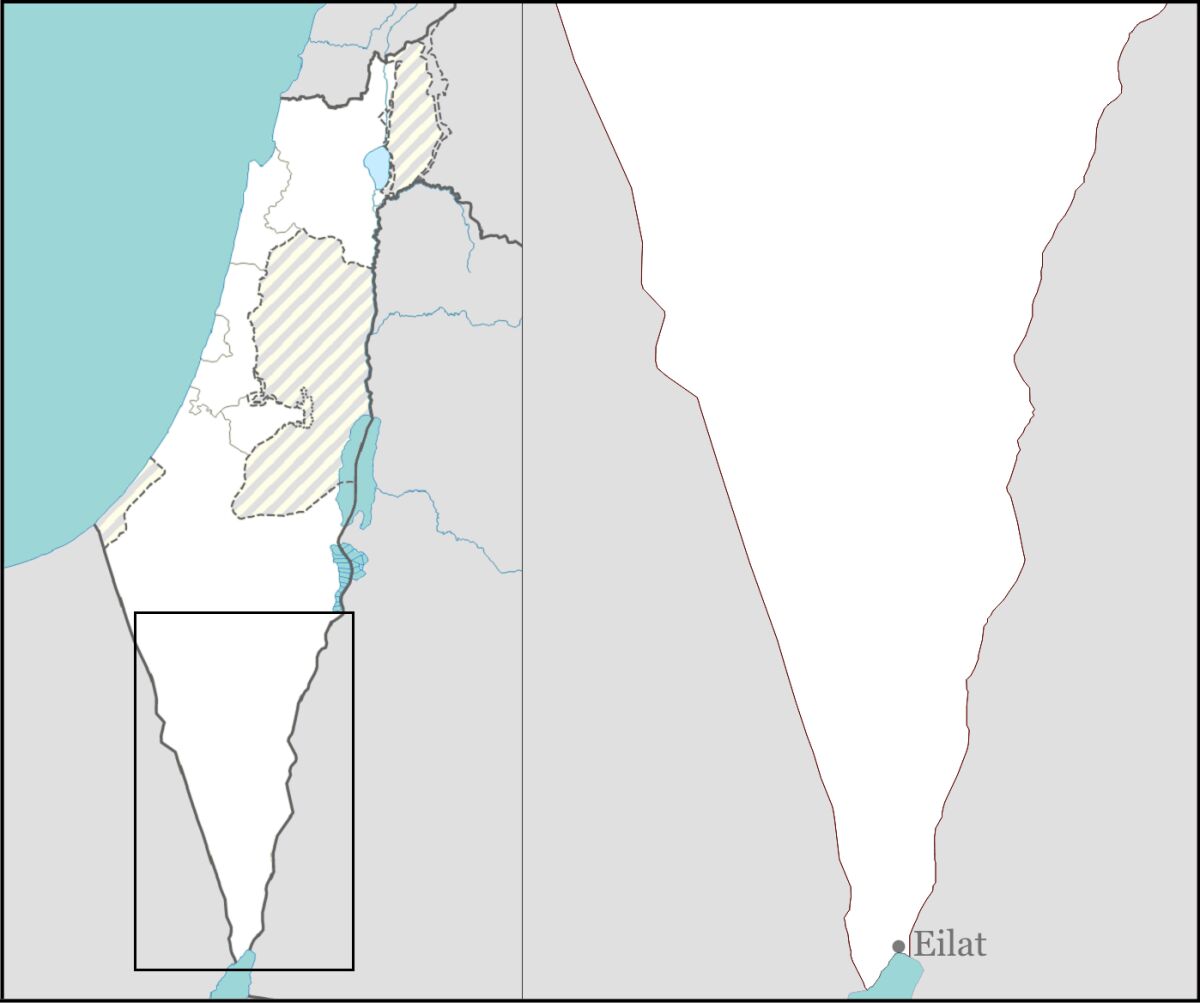

The Bible does describe Solomon having his southern navy fleet located at Yam Suph, on the shores of Ezion-Geber/Eloth (what is modern-day Eilat—see map right; 1 Kings 9:26). The name here thus clearly does refer to the Gulf of Aqaba.

Yet in modern Hebrew, Yam Suph indeed refers to the entire general Red Sea, including both gulfs (merely “tongues” of the wider Red Sea—see Isaiah 11:15-16). The New Testament Greek for the crossing site, Erethran Thalassan, likewise is used in antiquity to refer to the entire Red Sea. Why should the original title Yam Suph be any different?

And a nugget in the Exodus account likewise points to the recognition of the entire Red Sea and gulfs as Yam Suph. Exodus 10:19 describes the plague of crop-destroying locusts ending after the insects were drowned in Yam Suph. Note the map, right: The majority of Egypt (Lower and especially Upper) bordered on the main body of the Red Sea, as well as the Gulf of Suez. Why would the millions of locusts be flown all the way across the Gulf of Suez and the Red Sea, in order to deposit them in the narrow Gulf of Aqaba (if this really was the only stretch that could be referred to as Yam Suph)? Clearly, as it does today, the biblical Yam Suph did refer to more than “just” the Gulf of Aqaba. 1 Kings 9:26 does not preclude the Gulf of Suez.

In fact, 1 Kings 9:26 is some of the best evidence against a Gulf of Aqaba crossing. That’s because the wording used in the early Greek Septuagint translation is different—the name for this Gulf of Aqaba body does have a distinction from the name used in all 22 biblical references to the sea that the Israelites crossed! The Septuagint calls this Gulf of Aqaba sea in 1 Kings 9:26 Eschates Thalasses. The body of water in which the Israelites crossed, however (including the name of the sea in which the locusts were drowned!), is always referred to in the Septuagint, as well as in the New Testament, by the name Erythran Thalassan.

Thus, it becomes clear that the 2,300-year-old Jewish community, from which the Septuagint emerged, recognized this Gulf of Aqaba as distinct and different to the actual sea that the Israelites crossed!

One final point on this subject. Numbers 33 describes the “stations” of the Exodus. Verse 8 describes the Israelites crossing the Red Sea, and proceeding for three days into the wilderness of Etham, within which they camped at Marah, and then on to Elim (verse 9). Yet verse 10 has the Israelites arriving, again—before they reach Mount Sinai—at the Red Sea! How to explain this? But this fits perfectly with an initial crossing of the northern end of the Gulf of Suez, with the Israelites then following down south more or less along the direction of the coast toward Mount Sinai, in the southern part of the peninsula. It does not fit logically with a crossing at the Gulf of Aqaba, with Saudi Arabia’s al-Lawz located due east. (One proponent on the film, who dogmatically asserted that “Yam Suph” is none other than the Gulf of Aqaba, retraces a novel route that actually puts this second Israelite “Yam Suph” encampment on the shores of the main stretch of the Red Sea, well outside of the Gulf of Aqaba. The necessary peculiarity of this route, in order to fit with Numbers 33:8-11, is one thing—but it also torpedoes the attempt to singularly associate “Yam Suph” with the Gulf of Aqaba alone.)

All of that said, as with the identity of the Red Sea, there is even more debate surrounding the identities of the stations and landmarks of the Exodus on the way to the crossing—Succoth, Etham, Pi-hahiroth, Migdol, Baal-zephon, etc. There are all manner of different locations identified as “proof” of different crossing points related to the Bitter Lakes, Gulf of Suez and the Gulf of Aqaba. As such, we won’t go into them here.

Suffice it to say, one of the primary points given for the Aqaba crossing is the sheer mountainous approach to the sea, within which the Israelites became trapped (Exodus 14:3)—good evidence against the clearly plains-like, naturalistic Bitter Lakes theory. But the approach to the northwestern shore of the Gulf of Suez is also rugged and mountainous. The region around Attaka and Ain Sokhna, at the northwest part of the gulf, would fit nicely with the biblical account of the mountains that hemmed in the Israelites.

All that aside, the details of the distance and time frame of Israel’s journey out of Egypt provide some of the most fascinating and telling information about where the crossing would have taken place.

Hoofing It From a Fixed Starting Point

Located on the map (right) is the primary Israelite starting point: Avaris. This “Israelite city” was very effectively identified in the earlier Patterns of Evidence: Exodus documentary. Archaeological discoveries have helped to pinpoint this location as a sort-of “Israelite capital” in the wider, more generally established delta territory of the Land of Goshen. (It is also apparent that a contingent of Israelites—including Moses and Aaron—would have been further south, in or around the Egyptian capital Memphis; i.e. Exodus 12:31.)

Thus, in simplest form, we have two general options: Either a roughly 400-kilometer (250-mile) journey from this starting location to the Gulf of Aqaba, and from there a roughly 80-kilometer (50-mile) journey to Jabal al-Lawz; or, a roughly 130-kilometer (80-mile) journey to the Gulf of Suez, and from there a 240-kilometer (150-mile) journey to Jabal Musa. In other words: A huge journey to the sea crossing, then a short journey to the mountain (the Aqaba theory); or a short journey to the sea crossing, then a long journey to the mountain (the Suez theory). As below:

Put simply, the short-to-long route (above, red) is the only one that truly matches the biblical text. The journey to the Red Sea is covered in only around half a chapter’s worth of the Bible. The remaining journey from the Red Sea to Mount Sinai is covered in several chapters. This alone would indicate a shorter initial journey to the Red Sea, then a longer journey to Mount Sinai.

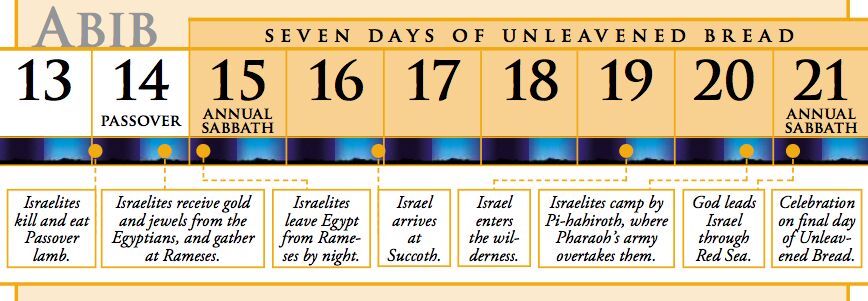

Josephus stated that it took only three days of journeying for the Israelites to reach the Red Sea. “But as they went away hastily, on the third day, they came to a place called Baalzephon, on the Red Sea” (Antiquities, 2.15.1). Long-standing Jewish (and Christian) tradition holds that the Israelites crossed the Red Sea seven days after the Passover (more on the reason for this further down). Only seven days until the crossing—or, according to Josephus’s account, three days of journey—an achievable trip to the Gulf of Suez, but an inconceivably short amount of time for the 400 kilometers (250 miles) across the Sinai Peninsula to the Gulf of Aqaba.

These numbers cannot fit with the journey to the Gulf of Aqaba. The case is made on Patterns of Evidence that the Israelites could have made it in a week, partly thanks to their physical fitness as slaves (even the term “running” was used on the film). But there were obviously children and elderly, people of all ages (Exodus 10:9, 12:37).

Some have tried to make even a three-day trek fit for the Gulf of Aqaba theory: If the Israelites walked nonstop for three full days and nights at the average walking pace of 5.6 kilometers per hour, they would be able to cover the 400-kilometer journey in time (just—you can do the math: 5.6 kph x 24 hours x 3 days = 403.2 kilometers). Exodus 13:21 is cited, describing God leading the Israelites by a pillar of fire by day and cloud by night.

But the verse says no such thing about such a continuous marathon feat of endurance. Just the opposite: The Bible describes three separate encampments along the way to the Red Sea (verse 20; Numbers 33:5-8).

The Bible states that it took roughly two months to reach the territory of Mount Sinai (Exodus 19:1, Numbers 33:3). 400 kilometers in a handful of days—80 kilometers in two months? The math just does not add up.

Another element to consider is that while a bulk of the Hebrews were located in Goshen, that wouldn’t have been entirely the case. Patterns of Evidence spends some time establishing the biblical numbers—roughly 2 million Hebrews leaving Egypt (i.e. Exodus 12:37). Again, note that the Exodus population figures constitute another fiercely contested issue. Going with these numbers, however: That many Israelites would not have been stationed at the singular location of Avaris. Rather, these mid-second millennium b.c.e. Semitic slaves are known to have been spread right across Egypt, including deep in the southern territory of Upper Egypt. The description of the 10th plague and spoiling of the Egyptians speaks to this, indicating that many of the Israelites’ dwellings were spread around the land, in and around Egyptian houses. Any Israelites in more distant locations (potentially days-journey away from Goshen?) would have been left far behind by a rapid charge across the north Sinai by a forward part of the Israelites on their way to Aqaba. Was that the way of it?

Or did it take a few days into the Israelite departure for the various groups of Israelites to catch up? This would fit well with a Gulf of Suez crossing, preempted by several encampments (such as apparently for the Sabbath, at Succoth) along the way.

Added to that, there is the simple matter of crowd size. Given a crowd spread of some 2 million people, replete with livestock and possessions, it would have taken the better part of a day’s journey for the people at the back to end up where the people at the front started off (with a potential crowd size many kilometers in length). And this would have only been immensely exacerbated if the Israelites were threading through the extremely narrow mountainous southeast of the Sinai, on the way toward Nuweiba Beach (one of the primary theoretical locations for a crossing of the Gulf of Aqaba).

Another element to consider here is the Pharaoh’s chase after the Israelites. Exodus 14:5 describes Pharaoh (based in Memphis) changing his mind immediately after “it was told the king of Egypt that the people were fled.” He subsequently pursued after them on horses and chariots, only finally catching up with them as they were arriving at the edge of the Red Sea. Are we to believe that his chariots and horsemen only finally caught up with them on the far side of the Sinai Peninsula—some 400 kilometers away?

In this same “distance” vein, there are other points that simply rule out a Gulf of Aqaba crossing, yet fit perfectly with the Gulf of Suez.

Of Wildernesses, Water and Complaining

The Bible describes only one “wilderness” before the Red Sea crossing—and then three entirely different wildernesses from the Red Sea to Mount Sinai (Josephus called them entire countries). This fits perfectly with the distance-layout for a Gulf of Suez crossing. But are we to believe that, for a Gulf of Aqaba crossing, the 400-kilometer journey across the Sinai Peninsula is referenced as barely a single wilderness—whereas the last 80-kilometer stretch to Jabal al-Lawz constitutes three different wildernesses, or countries? Again, in this respect, the math is the wrong way around.

But this biblical layout fits hand-in-glove with a Suez crossing: The single, shorter desert region just before the Gulf of Suez, followed by the well-known, standard geographical division of the Sinai Peninsula into three separate “wildernesses”: the northern Dune Sheet, the central Tih Plateau and the southern mountainous Sinai Massif.

The Bible also describes the Israelites “pitching” in only three different locations before the sea crossing—but it describes them pitching in eight different locations after it, on the way to Mount Sinai (Numbers 33:5-15). Which route fits better?

Further, it is only after the Red Sea crossing that the Israelites begin to complain about water (Exodus 17:1-2). Why only in the short stretch from Aqaba to al-Lawz? Why no mention of water during the massive 400-kilometer stretch across the Sinai? And it is only after the Red Sea crossing that God starts to give the Israelites manna (Exodus 16). Why only in the final short stretch? Why not on the 400-kilometer hike? But these events do fit with the long desert journey deep into the Sinai Peninsula, following the short journey to a crossing at the Gulf of Suez.

Seabed Evidence of Crossing?

One of the most alluring things about the Patterns of Evidence: Red Sea Miracle documentary was the promise of potential chariot remains found at the bottom of the Gulf of Aqaba. For decades, this has been a topic on the fringes of the archaeological world, after the late amateur archaeologist Ron Wyatt declared that his diving team had found just that.

The second part of the documentary described some of Wyatt’s background. This was necessary, because he is looked upon poorly in the archaeological world. A nurse anesthetist by profession, Wyatt traveled all over the Middle East looking for biblically significant artifacts. He claims to have made numerous significant discoveries besides the chariot remains in the Gulf of Aqaba (and it was largely thanks to him that the Jabal al-Lawz site came into vogue), including: Noah’s ark, the Tower of Babel, Goliath’s sword, the real location of Jesus’s crucifixion, the ark of the covenant, even the “blood of Jesus” preserved on the ark—which, after he purportedly had it tested, came back to reveal “24 chromosomes”—“23 from Mary, and one from God.” He also claimed to have handled the Ten Commandments contained within the ark, as well as having communed with angels who were guardians over it. He even claimed to have been met by Jesus during his activities at the Garden Tomb. (These peculiar events—and more—are detailed in the lengthy book of his associate Jonathan Gray, entitled Ark of the Covenant. For more on this subject, see our article here.)

The main problem with several of Wyatt’s “discoveries” is that they are presented with little-to-no evidence, and stern rebuttals for those who ask (as highlighted in the book Holy Relics or Revelation, by the Standish brothers). There are somehow no photos of the ark of the covenant (excepting one extremely blurry image, in which nothing is discernible). No lab report of the “24-chromosome blood.”

As far as the Gulf of Aqaba “chariot wheels” are concerned: While there are photos of crooked coral formations, none of them can be proved to be the remains of chariots (and a marine biologist featured on Patterns of Evidence served to only disprove the possible preservation of such remains). The Patterns of Evidence film did a good job in providing some detail relating to ongoing diving efforts for remains in the Gulf of Aqaba by a group of enthusiasts. But no hard evidence was revealed.

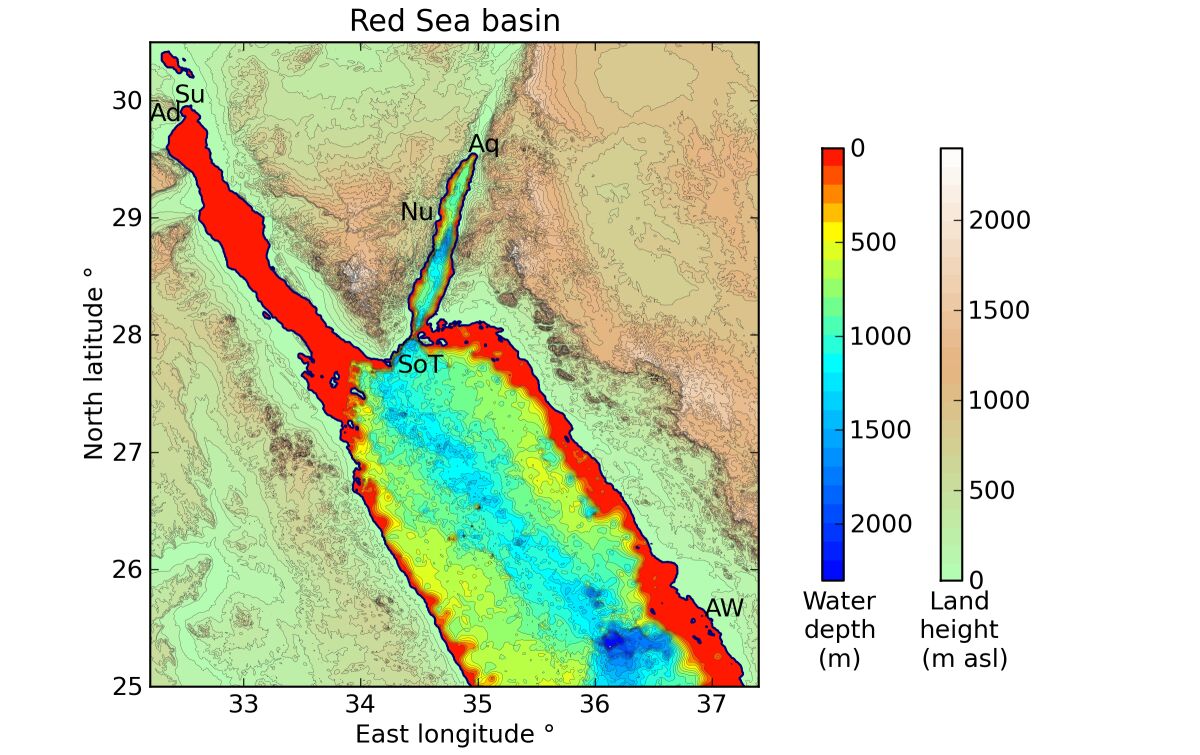

But on this point, a Red Sea crossing at Aqaba brings up a problem: The seabed is a veritable Grand Canyon, reaching depths of 2,000 meters (6,600 feet) below sea level (after all, it is a continuation of the Jordan Rift Valley and Dead Sea Transform plate boundary). On the documentary, this was a point of attack by proponents of the Bitter Lakes crossing. But it was defended by proponents of the Aqaba crossing, in that a miracle-working God would have had no problem in helping the Israelites through this stretch of seabed.

The Israelites picking their way through a “Grand Canyon” is one thing; what beggars belief is that the Egyptians would follow them in on chariots. God would not have needed to kill the Egyptians with the walls of water smashing together—the terrain alone would have surely done so.

A couple of so-called “underwater land bridges” that span Aqaba were pointed out as possible crossing points. One is from Nuweiba Beach, near the center of the west coast of the Gulf of Aqaba. While it could be construed as a “bridge” compared to the immense deeps in certain parts of the gulf, it is still some 850 meters (2,800 feet) below sea level in the center—a yawning chasm. (For perspective, that’d be like walking alongside a wall of water taller than the Burj Khalifa, pictured right—at the shallowest central point of the gulf. Given water weighs one ton per cubic meter, if these walls crashed together, you can forget about anything being preserved.)

Interestingly, an initial number presented in support of the Nuweiba crossing theory by Ron Wyatt, Jonathan Gray and others was that the land bridge reached a maximum depth of “only” 200–300 meters (700–1,000 feet; of course, still a colossal depth). This claim was made in citing a chart from the British Admiralty (the official authority for charting the Red Sea), and came to the attention of the British Hydrography Office of the Department of Defense. They issued a statement in 1995 correcting the claim, stating that “[t]here is no evidence in the Hydrographic Office of a ‘bridge’ crossing the Gulf of Aqaba.” Furthermore, they stated that the chart was actually a U.S. one that had been misconstrued, and that “[d]epths along the suggested route of the bridge reach a maximum of 850m (2800 feet) and not the stated 300m (1000ft). Contrary to Mr. Gray’s statement, the “Sand Bridge” is not now, and never has been a recognizable feature on British Admiralty charts. Nor is it recognizable on the US chart held by Mr. Gray.”

Also interesting is the reply from the Wyatt camp, describing the British Admiralty as an organization “composed of Biblical doubters,” whose state-of-the-art depth-charting instruments could have been “distorted by strong currents” (this, despite the fact that the Gulf of Aqaba is a comparatively calm seaway. For more on this subject—including a good appraisal of such claims and counter-claims—see Colin and Russell Standish’s book Holy Relics or Revelation).

Nuweiba crossing site aside, the other Gulf of Aqaba crossing option presented on the film is at the very bottom of the Sinai Peninsula, at the Straits of Tiran. Parts of this crossing are as shallow as 15 meters deep (and there is even a pair of islands in the middle of the straits). Container ships have to exercise some caution crossing through here. But the crossing also includes the immediate navigation of a canyon at the near edge, 300 meters deep (a corridor lane used by the container ships), with a 60 percent incline on the eastern side. Not to mention how much more the proposed lengthy journey itself, to get to the crossing point at the very bottom of the Sinai Peninsula (some 500 kilometers, or around 300 miles), strains the biblical account.

What wasn’t mentioned on the documentary, though, is how well the Gulf of Suez would fit, with its utterly smooth seabed. Much of the sea floor of the northern Suez reaches only 40 meters deep, with gentle inclines on both ends—perfect for the Israelites on foot, as well as for the chariots and horsemen of Egypt to follow. Josephus stated that the dried seabed was like a “road.” Psalm 106:9 describes the seabed as being like “a wilderness.” Compare the two gulf seabeds on the topographical map below:

But all that aside, what must be the greatest evidence for a Suez Crossing is the vital holy day symbolism.

Holy Day Symbolism

As mentioned above, the crossing of the Red Sea is to this day traditionally commemorated on the seventh day following the Passover—the last day of the feast of Unleavened Bread. This seven-day festival, with its “high holy days” on the first and last of the seven days, is commanded in Leviticus 23:6-8. This festival pictures the complete removal of leaven, a symbol of sin, from our lives. In the Bible, Egypt serves as a metaphor for sin; Pharaoh as a metaphor for Satan. We read of the death of the firstborn on the night of the Passover, in order to free the Israelites and pave the way for their escape—and then the final destruction of the Egyptian army, the last “hold” on the Israelites, on the final holy day of Unleavened Bread. There is also the religious symbolism of immersion/baptism/purification of the Israelites as a body going “through” the waters of the Red Sea—“purified” of sin.

Note Exodus 12:16-17 (from the New King James Version): “On the first day there shall be a holy convocation, and on the seventh day there shall be a holy convocation … So you shall observe the Feast of Unleavened Bread, for on this same day I will have brought your armies out of the land of Egypt.”

From the Herbert W. Armstrong College Bible Correspondence Course (Lesson 30): “The miraculous opening of the Red Sea and the completion of the Israelites’ escape from slavery took place before dawn on the seventh and last day of Unleavened Bread. Then on the daylight part of this annual holy sabbath, there was great rejoicing in celebration of their complete delivery from bondage in Egypt (Exodus 15:1-21).” The “song of Moses,” in Exodus 15, therefore essentially serving as a worship service on this final holy day.

This seventh-day crossing was not just about leaving a piece of Egyptian territory, and on any old day at that. This was, more properly, about freedom from the grip of sin and Satan.

This all fits with a closer sea crossing, accessible within the first week of journey out of Egypt.

In similar manner, the giving of the law on Mount Sinai is anchored to the next holy day, the feast of Pentecost, or Shavuot, between six and seven weeks later (Exodus 19:1-2, Leviticus 23:9-22). This holy day pictures God’s covenant with His chosen people, His giving of the law (and, as far as the New Testament is concerned, the giving of the Holy Spirit on this day, resembling flames of fire—Acts 2). Again, fitting with a longer journey, a longer space of time, on the other side of the Red Sea.

It is no coincidence that each sacred day—Passover, the first day of Unleavened Bread, the last day of Unleavened Bread and Pentecost—matches with a major event of the Exodus. The holy day calendar unlock the full meaning of the Exodus, both physically and spiritually.

And alongside this spiritual significance, there is also the physical significance of Israel controlling, at key times throughout its history, the very territory that included the mountain of God. This was the case during the reign of King Solomon, whose initially illustrious, rich and powerful Davidic-dynasty kingdom typifies that of the coming Messiah. And that was the case in recent history, in 1967, during the Six-Day War—not only the significant recapture of Jerusalem for the first time in two millennia, but at the very same time the reclamation of the mountain of God in Sinai, with the recapture of the Sinai Peninsula.

Again, as mentioned in the above-quoted Galatians 4—Jerusalem and Mount Sinai, together—a mountain that directly “corresponds to the present Jerusalem” (verse 25, Revised Standard Version). And can you guess when this happened—when the Israeli Army “set their camps” in the Sinai? June 5-6, 1967—as with the ancient Israelites in Exodus 19, just days before Shavuot/Pentecost!

Jabal Musa was also the area in which remarkable plans began for a joint Jewish-Muslim-Christian “peace center” following the later stunning peace accords between Egypt and Israel (plans which were later sadly put to the side, following the assassination of the Egyptian president Anwar Sadat).

None of this symbolism can be said for the obscure northwestern region of Saudi Arabia.

So Why Was It Not Mentioned?

Why was the Gulf of Suez option not presented in the Patterns of Evidence film? In fact, more time was given to another theory, about a now dried-up potential crossing in the Israeli Negev desert at the site of Timna. Essentially, the Gulf of Aqaba was presented as the option ‘if you believe the biblical account,’ and the Bitter Lakes ‘if you prefer naturalistic explanations.’ Why?

The Bitter Lakes theory has long been a classic apologists’ version of events, a way to scientifically “explain” the Exodus account. Selecting this as a flipside argument is understandable, and a good choice. And the film did quite a good and certainly thorough job in presenting the Aqaba theory—necessary, given the amount of discourse about it today. But where was the Suez theory?

It seems that the singular focus on the Aqaba theory must have come entirely from a preconceived bias toward Jabal al-Lawz as the (apparently) most “biblically accurate” site of Mount Sinai. But as we have briefly covered, that’s far from the case—and even still, a stronger biblical case could be made for a Gulf of Suez crossing on the way to Jabal al-Lawz, than an Aqaba-to-al-Lawz.

Also, there is the point that traditional Christianity has “done away with” the observance of festivals such as the Days of Unleavened Bread. As such, much of the significance of the important festival has been lost or forgotten, together with the symbolic connection of the seventh-day Red Sea crossing. (This, despite the fact that this feast continued to be kept by the New Testament church—i.e. 1 Corinthians 5:6-8, Acts 20:6.) As such, certain theories have allowed for a far longer journey to the Red Sea.

Still, the two-part documentary totaled four hours—leaving ample time to give attention to a Gulf of Suez crossing. Instead, it was simply passed over as ‘most scholars dismiss.’ But a bulk of scholars also dismiss a Gulf of Aqaba crossing—or any crossing at all.

The documentary did get into a lot of technical biblical details. Detailed Bible study is vital—there’s not enough of it in the archaeological world. That’s where Patterns of Evidence has delivered a refreshing element to a rather stagnant world of scholarly doubt and skepticism.

But it can be too easy to get caught up in the “seaweed” (suph)—and lose the entire sea (yam). The sacred biblical symbolism and message of the departure from Egypt and crossing of the Red Sea is indelibly tied to the Passover/Days of Unleavened Bread, picturing for us the departure from and complete removal of sin. And the arrival at Mount Sinai, with the giving of the law and the flames of divine fire, are inseparable from the symbolism of the day of Shavuot/Pentecost—picturing our covenant to and relationship with God. That is the real biblical message of the Exodus.

Interpolate that onto a physical map; now there’s a biblical account that fits perfectly with a crossing at the Gulf of Suez.

Article updated 13/06/24.

Read More: