The 10 plagues of Egypt constitute one of the strangest collections of miracles in the Bible. Water turned to blood, legions of frogs, dust turned to lice, boils—nowhere else in the Bible do we see such a peculiar display of divine judgment.

Have you ever wondered why God sent such an eclectic mix of plagues? And why He sent 10? He could have easily crushed Egypt and freed the Israelites through just one plague. Why didn’t God just intensify plague number seven—the hail—and be done with it?

There is a fascinating reason why God performed so many powerful and peculiar miracles. He didn’t send the 10 plagues to merely free the Israelites or to punish Egypt’s Pharaoh and his people. In Exodus 12:12, God says, “[A]gainst all the gods of Egypt I will execute judgments: I am the Lord.”

Egypt at the time was the world’s dominant power, and it possessed one of the most widespread, complex and ancient religions on Earth. God used the plagues to warn and punish an entire religious and political system—and to free an entire civilization from slavery to false religion!

The One True God

By the time of the 10 plagues, Israel had dwelled in Egypt for hundreds of years. At first, during the time of Joseph, the Israelites were welcome guests. But as the number and power of the Israelite people grew, Egypt’s pharaohs began to see the Israelites as a threat. By the time Moses was born, the Israelites were a slave people who had lost their true identity.

Exodus 2:23 shows that the children of Israel cried out for deliverance. But this verse does not describe them crying out to “their God,” nor does it use any of God’s names. These people were seeking help from any deity that could provide it.

The population, in fact, had begun to worship the gods of Egypt (Joshua 24:14). They had been so corrupted by Egypt’s religion that they no longer even knew who the true God was (Exodus 3:13).

Through the 10 plagues, God was making Himself known to the Egyptians and to the Israelites. The Israelites actually experienced the first three plagues because they needed to learn who God was!

Some experts believe that Egypt had a pantheon of as many as 2,000 pagan gods and goddesses. Through the plagues, God proved that He was the one and only all-powerful, divine Being of the universe. “And God said unto Moses: ‘I am that I am’” (Exodus 3:14). God conveyed this message to Moses, and then He used this great man and the 10 plagues to convey the same message to both the Egyptians and the Israelites.

The essential purpose of the 10 plagues is this: God was causing the most powerful civilization on Earth, and His own people, to recognize that “I am that I am.”

First Blood: Snake Gods

It is notable that the first words Pharaoh uttered to Moses and Aaron concerned the identity of their God. “And Pharaoh said: ‘Who is the Lord, that I should hearken unto His voice to let Israel go? I know not the Lord, and moreover I will not let Israel go’” (Exodus 5:2). To Pharaoh, Moses’s God was just another deity.

But then Moses performed a miracle that showed God’s identity in relation to Pharaoh, his magicians and the Egyptian gods: “… Aaron cast down his rod before Pharaoh and before his servants, and it became a serpent. Then Pharaoh also called for the wise men and the sorcerers; and they also, the magicians of Egypt, did in like manner with their secret arts. For they cast down every man his rod, and they became serpents: but Aaron’s rod swallowed up their rods” (Exodus 7:10-12).

There is more to this event than meets the eye. To the ancient Egyptians, a snake swallowing other snakes was a known religious refrain.

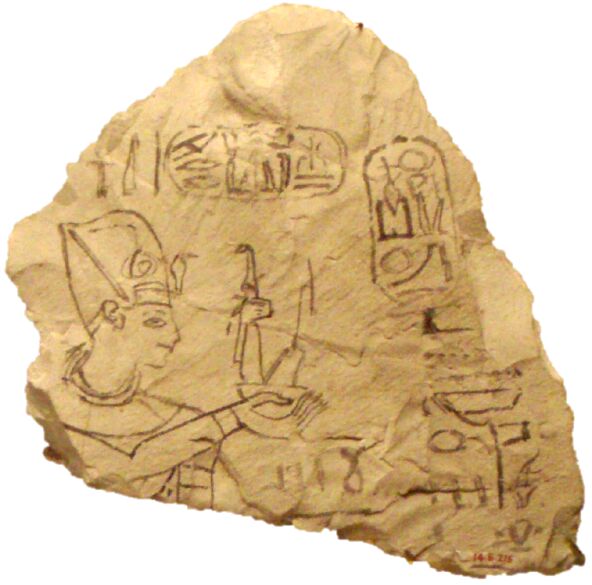

In Egyptian mythology, the powerful primordial snake god Nehebkau is considered the “original snake.” His image was depicted as a protective deity on ivory rods. Worship of him was especially popular at this time in Egypt’s history (middle second millennium b.c.e.). According to the Coffin Text Spells (ancient Egyptian mythological accounts inscribed around 2100 b.c.e.), Nehebkau swallowed seven cobras, giving him power against harm from any magic.

The Hebrew snake swallowing the Egyptian snakes, in the name of the “God of Israel,” would have been a startling display of supremacy.

Nehebkau was also a central god to the Egyptian afterlife (his job was to reunite the dead with their living soul). That’s why it is significant that this miracle occurred first, before the ensuing fatal plagues.

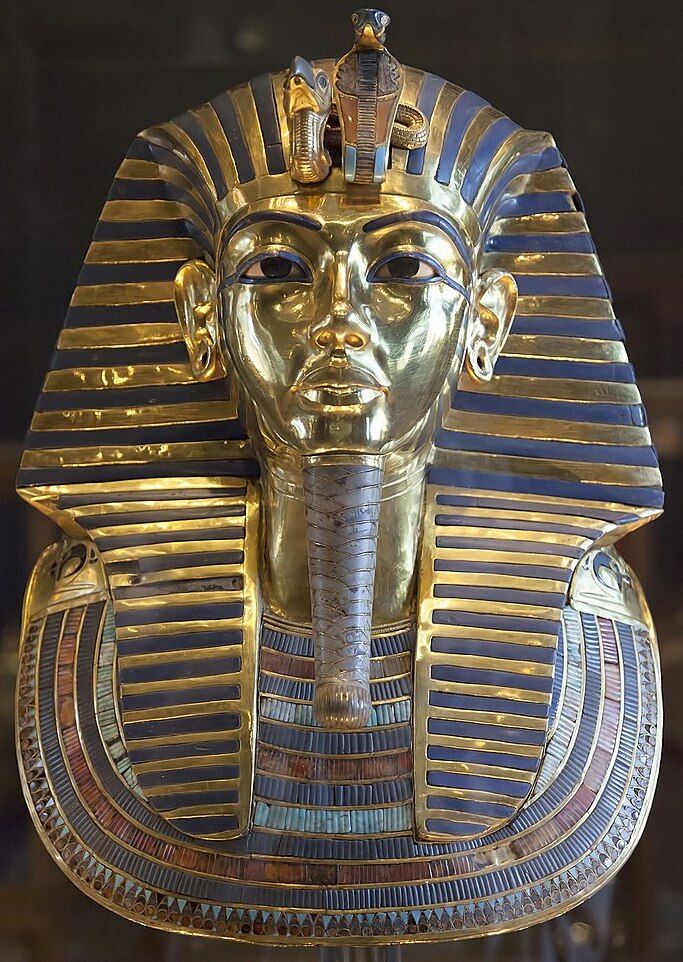

God’s actions through Moses and Aaron would also have been seen as an insult to numerous other Egyptian snake deities, such as the goddess Wadjet. Depicted as a snake coiled around a pole, this goddess was worshiped by the Egyptians as the “Protector of Lower Egypt,” the region in which Goshen (and therefore the Israelites) was located. You might have seen pictures of her cobra symbol worn on the headdresses of pharaohs; this symbolized their dominance over Lower Egypt. When Moses’s snake swallowed the other snakes, the message was clear: The God of Israel, not Wadjet nor Pharaoh, was the supreme power in Lower Egypt!

Before the plagues even began, God delivered this startling symbolic blow to Egypt’s gods and Pharaoh. But it wasn’t enough: “And the Lord said unto Moses: ‘Pharaoh’s heart is stubborn, he refuseth to let the people go’” (verse 14).

1. Water to Blood

With the first plague, God struck Egypt’s most important resource: the Nile River. “[A]nd he [Aaron] lifted up the rod, and smote the waters that were in the river, in the sight of Pharaoh, and in the sight of his servants; and all the waters that were in the river were turned to blood” (Exodus 7:20). The Nile provided Egypt with a constant source of fresh water. Its nutrient-rich floodplains were Egypt’s breadbasket.

Turning the Nile to blood was another targeted attack on one of Egypt’s most important gods: Osiris, the god of fertility, vegetation and agriculture. The Egyptians considered the Nile River to be the “bloodstream” of Osiris. As the chief god of the Nile, Osiris gave life to the Egyptian empire. When God turned the Nile to literal blood, the river (and its god) became the source of widespread death and suffering.

This miracle attacked other gods as well: Khnum, god of the source of the Nile; Hapi, the god who presided over annual flooding; Sopdet, goddess of fertility-brought-to-soil-by-Nile-floodwater. It also insulted other Egyptian deities, including Nu, Naunet, Tefnut, Nehet-Weret and the fish-goddess Hatmehit.

Although Pharaoh’s magicians successfully replicated this plague, they couldn’t make it stop (verse 22). Deities such as Taweret—the pot-bellied, hippo-headed, crocodile-tailed “Mistress of Pure Water”—were not able to cleanse the Nile or all the other water that had likewise miraculously turned to blood (verse 19).

God’s onslaught on the gods of the Nile River continued for one week. But Pharaoh still refused to obey God’s command. So Moses and Aaron returned to the royal court.

2. Frogs

“Thus saith the Lord: Let My people go …. And if thou refuse to let them go, behold, I will smite all thy borders with frogs. And the river shall swarm with frogs, which shall go up and come into thy house, and into thy bed-chamber, and upon thy bed, and into the house of thy servants, and upon thy people, and into thine ovens, and into thy kneading-troughs” (Exodus 7:26-28).

Besides being gross, this plague would have had a dramatic impact on the Egyptian mind. The best-known Egyptian frog deity is the goddess Heqet. Heqet, and frogs in general, symbolized childbirth and midwifery, as well as resurrection. These motifs are closely tied to the Israelite story in Egypt.

To stop the immense population growth of the Israelites, Pharaoh had previously ordered that all newborn males be drowned by the midwives in the Nile (Exodus 1:15-22). Now, with the second plague, Pharaoh was inundated with these symbols of childbirth, midwifery and resurrection literally pouring back out of the Nile! Surely the symbolism was not lost on Pharaoh.

Moses told Pharaoh: “… ‘Be it according to thy word; that thou mayest know that there is none like unto the Lord our God. And the frogs shall depart from thee, and from thy houses, and from thy servants, and from thy people; they shall remain in the river only’” (Exodus 8:6-7). Was Moses also hinting at the Israelite connection to this plague—with a prophetic description of Israel’s departure from Egypt?

Nevertheless, Pharaoh’s heart was again hardened.

3. Dust to Lice

“… Aaron stretched out his hand with his rod, and smote the dust of the earth, and it became lice in man, and in beast; all the dust of the land became lice throughout all the land of Egypt” (Exodus 8:17; King James Version).

The Hebrew word translated as “lice” is only used in this biblical context, so the exact identity of this critter is unclear. Other translations describe “fleas,” “sandflies,” “gnats,” “ticks” or “mosquitoes.” The Hebrew word indicates a creature that digs into the skin.

Regardless, the ground literally came alive with parasites. This plague would have been an affront to, among others, Geb, Egypt’s chief earth god.

It was also aimed quite pointedly at a specific part of Egypt’s society: the priests and religious leaders. Egypt’s religious leaders went to extreme lengths to keep themselves clean and pure, especially of lice. Egyptian priests even removed their eyebrows and eyelashes—anything that could host parasites!

This phobia for lice was noted by Herodotus, the famous fifth-century Greek historian: “The priests shave their bodies all over every other day to guard against the presence of lice, or anything else equally unpleasant, while they are about their religious duties …. [They] wear linen only, and shoes made from the papyrus plant …. They bathe in cold water twice a day and twice every night—and observe innumerable other ceremonies besides” (The Histories).

This plague would have been a veritable nightmare for Egypt’s religious leaders! And they were entirely powerless to stop it.

Notably, it is with this plague that the magicians admitted defeat. With their homes and bodies crawling with lice, they told Pharaoh, This is the finger of God. But Egypt’s leader was unmoved. His “heart was hardened, and he hearkened not unto them …” (verse 15). So the plagues continued.

4. Swarms

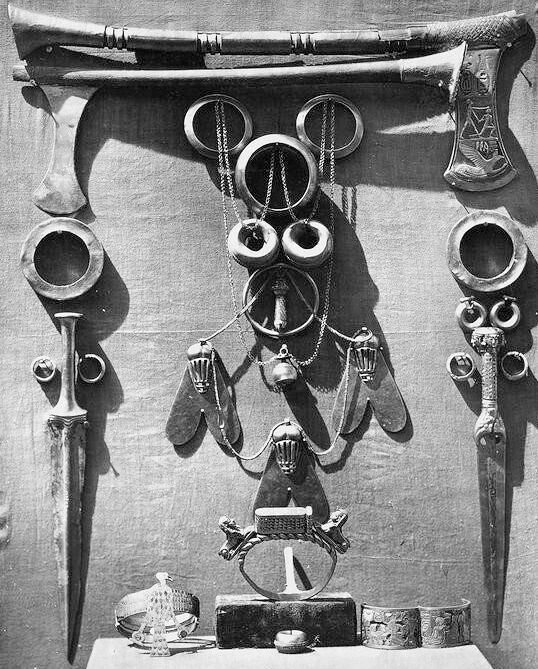

Flies and beetles were popular charms in ancient Egypt. Flies adorned ritualistic objects; soldiers and leaders were decorated with a pendant known as the “Order of the Golden Fly.” The fly served as a symbol of relentless determination and bravery.

It’s hard to imagine this affection for flies remaining after the fourth plague hit. “[B]ehold, I will send swarms of flies upon thee, and upon thy servants, and upon thy people, and into thy houses; and the houses of the Egyptians shall be full of swarms of flies, and also the ground whereon they are. … [A]nd there came grievous swarms of flies … the land was ruined by reason of the swarms of flies” (Exodus 8:17, 20).

The original text does not use the word “flies”; it refers to them simply as swarms. Based on the translation of the ancient Greek Septuagint, most scholars identify this insect as the dogfly, similar to the March fly, horsefly, botfly or gadfly. As some of our readers may have experienced, these blood-sucking flies can inflict a painful bite. They can also be deadly, as they transmit various diseases such as anthrax and tularemia.

The effect these flies had on Egypt was gruesome. Psalm 78:45 states that these swarms “devoured” the Egyptians.

Various deities associated with flies and insects include the goddesses Wadjet, Iusaaset and Khepri, who was depicted with the head of a beetle. Bees were said to come from the tears of the sun god, Ra, and certain wasp-like insects made up part of the official royal title of the pharaoh.

To end this plague, Pharaoh acquiesced and agreed to release the Israelites (ironic, given that flies symbolized unwavering Egyptian determination). But unfortunately for his people, he changed his mind again after the swarms departed.

5. Death of Livestock

“Behold, the hand of the Lord is upon thy cattle which are in the field, upon the horses, upon the asses, upon the camels, upon the herds, and upon the flocks; there shall be a very grievous murrain. … [A]nd all the cattle of Egypt died …” (Exodus 9:3, 6).

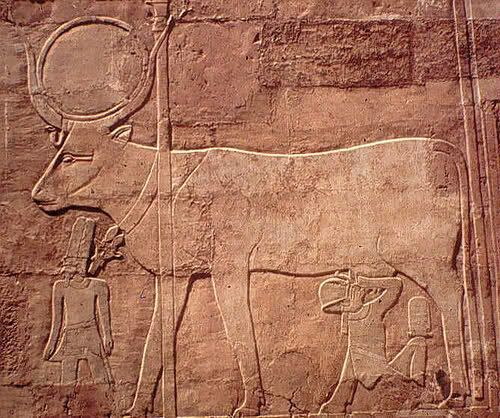

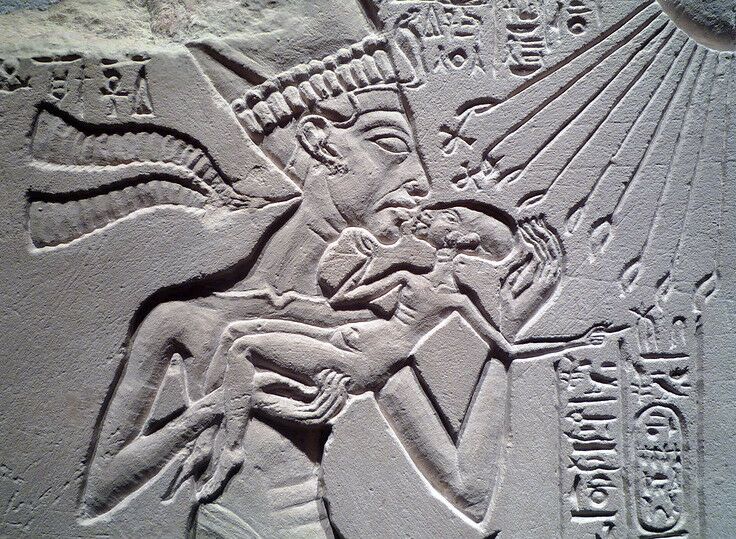

While this plague cut deep at countless Egyptian animal gods, its attack was most pointedly against cattle deities—the most significant animals in the Egyptian pantheon. Particularly important was the cow-goddess Hathor, daughter-consort of Ra and “mother of the pharaoh” (who himself was stylized as a bull). Egyptian wall art commonly depicts pharaohs suckling from the udder of Hathor.

Another famous deity is the Apis bull, a “son of Hathor” and manifestation of the pharaoh. Only one such physical bull could exist at a time, and once the bull died, it was mourned almost as if Pharaoh himself had died, including being mummified and interred in a massive sarcophagus weighing up to 60 tons.

Verse 6 indicates that the Apis bull at this time must have died—a blow to Pharaoh.

The Egyptians considered the Israelite manner of handling livestock a blasphemous “abomination” (Genesis 46:34). So for the Egyptians to see their own cattle dying en masse while every Israelite cow was spared would have been distressing. Evidently Pharaoh himself couldn’t quite believe it and sent his own messengers to verify if the Israelite cattle truly had been spared (Exodus 9:7).

Some scholars postulate that God destroyed Egypt’s livestock via a plague of anthrax. This makes sense, considering the previous plague; perhaps the swarms of flies transmitted the anthrax to the cattle. Whatever the case, this plague still did not breach Pharaoh’s hard heart. “… But the heart of Pharaoh was stubborn, and he did not let the people go” (verse 7).

6. Boils

The next plague literally hobbled the nation, forcing the people to their beds. Exodus 9:11 shows that even the magicians were not able to stand upright as a result: “And the Lord said unto Moses and unto Aaron: ‘Take to you handfuls of soot of the furnace, and let Moses throw it heavenward in the sight of Pharaoh. And it shall become small dust over all the land of Egypt, and shall be a boil breaking forth with blains upon man and upon beast, throughout all the land of Egypt’” (Exodus 9:8-9).

This epidemic of boils was an affront to numerous Egyptian deities, such as Sekhmet, goddess of epidemics and healing; Thoth, god of medical knowledge; Isis, goddess of healing; Nephthys, goddess of health.

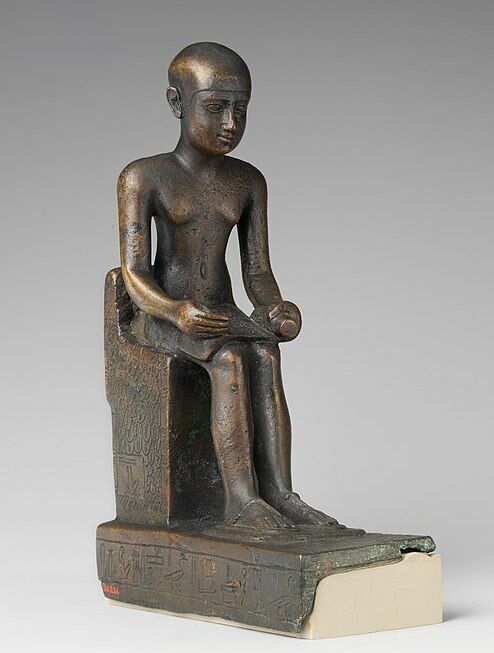

But it was also an affront to the much-prized Egyptian doctors, famous in the ancient world for their knowledge in medicine, surgery, dentistry, even prosthetics, with known complex medical texts dating back more than 4,500 years. So venerated were the doctors that the physician Imhotep, who served under Pharaoh Djoser (circa 2600 b.c.e.), became deified as the “god of medicine.”

The way that Moses initiated this plague, tossing ash from a furnace into the air, is also interesting. The word for furnace refers to a “kiln,” i.e. a brick-kiln—a device the Israelites would have known well. Exodus 5 describes the blistering, crippling labor forced upon the Israelites specifically in making bricks.

Thus, in another apparent turn of poetic justice, the Egyptians became crippled and blistered from the same brick-making source of torment. But not even a plague of painful sores was enough to change the mind of Egypt’s king.

7. Hail and Fire

The next plague would have been truly petrifying. “[A]nd the Lord sent thunder and hail, and fire ran along upon the ground …. [F]ire mingled with the hail …. And the hail smote throughout all the land of Egypt all that was in the field, both man and beast; and the hail smote every herb of the field, and brake every tree of the field” (Exodus 9:23-25; kjv).

This plague utterly destroyed everything and everyone not protected by substantial shelter. The sky-goddess Nut, who was supposed to protect the land from heavenly destruction, was evidently missing. So was her father, Shu, the “calming” god of the atmosphere. Gods of animals and agriculture (Set, Isis, Osiris and others) were also missing in action.

This plague also would have struck at Egyptian beliefs surrounding the afterlife. The reference to fire is notable: To be incinerated was considered the worst punishment to the Egyptians. Without a body, there was nothing to mummify, which meant no afterlife. (Even the damage to victims by hail would have been problematic, as Egyptians went to great lengths to ensure that the dead bodies were preserved as intact as possible.) This afterlife-affliction was made worse by a primary crop destroyed by this plague—flax (verse 31). Flax was essential for wrapping mummies.

With this plague, Pharaoh began to grow desperate. He finally admitted sin and recognized the supremacy of Israel’s God. “And Pharaoh sent, and called for Moses and Aaron, and said unto them: ‘I have sinned this time; the Lord is righteous, and I and my people are wicked. Entreat the Lord, and let there be enough of these mighty thunderings and hail; and I will let you go, and ye shall stay no longer’” (verses 27-28).

Why the admission of sin and wickedness—and why now?

In ancient Egypt, the pharaoh was the primary intermediary between his people and the gods. The pharaoh was personally responsible for Maat, “cosmic order,” maintaining balance in the land. “Disorder had to be kept at bay,” states Encyclopedia Britannica. “The task of the king as the protagonist of human society was to retain the benevolence of the gods in maintaining order against disorder.”

Perhaps Pharaoh felt he could retain some order amid the earlier plagues, but with this one—crashing hail, deafening thunder, blinding lightning, raging fires—the entire land was in utter chaos. With the hail, Pharaoh’s capacity for maintaining any semblance of Maat had vanished. And everyone knew it.

When the plague ended, however, Pharaoh changed his mind again, despite the pleading of his servants to simply let the Israelites go (Exodus 10:7).

8. Locusts

Plagues of locusts are not uncommon in the Middle East and Africa. But what here befell Egypt was on another level entirely. “And the locusts went up over all the land of Egypt …. For they covered the face of the whole earth, so that the land was darkened; and they did eat every herb of the land, and all the fruit of the trees which the hail had left; and there remained not any green thing, either tree or herb of the field, through all the land of Egypt” (Exodus 10:14-15).

With this plague, all remaining plant life, including the new crops of wheat and spelt that had not emerged at the time of the hail (Exodus 9:32), were devoured.

This plague struck at a number of important crop deities, including the grain gods Neper, Nepri, Heneb and Renenutet, as well as Isis and Set, two gods responsible for protecting the nation’s crops.

With the total destruction of crops, the Egyptian population now faced the prospect of starvation. “Then Pharaoh called for Moses and Aaron in haste; and he said: ‘I have sinned against the Lord your God, and against you. Now therefore forgive, I pray thee, my sin only this once, and entreat the Lord your God, that he may take away from me this [deadly plague]” (Exodus 10:16-17).

Moses obliged, but Pharaoh again changed his mind. Judgment was now due upon the greatest Egyptian god of all.

9. Darkness

Among all of Egypt’s gods, none was venerated as much as Ra, the all-powerful sun-god. This god, variously worshiped as Re, Amon-Ra, Atum or Aten, had power over all other gods. Worship of the solar deity was so important that during the 13th-century b.c.e. reign of Akhenaten, the pharaoh banned worship of any other gods besides him.

The ninth plague was a direct assault on Ra. “And Moses stretched forth his hand toward heaven; and there was a thick darkness in all the land of Egypt three days; they saw not one another, neither rose any from his place for three days …” (Exodus 10:22-23). The New Living Translation says it was a “darkness so thick you can feel it” (verse 21). As darkness prevailed, Egypt’s greatest, most powerful god was exposed as entirely powerless.

The darkness was a warning to Pharaoh himself, who was considered the “son of the sun.” To add insult to injury, verse 23 shows that while the Egyptians were covered in thick darkness, God’s people in the land of Goshen were bathed in bright sunlight!

The first nine plagues built up to the 10th and thus could be categorized separately (Exodus 12:12). The number nine was significant in Egyptian religion. Regional pantheons throughout Egyptian history were worshiped as enneads, “nines,” or groups of nine deities. The most famous was the Great Ennead of Heliopolis, led by the sun god Atum and consisting of his descendants Shu, Tefnut, Geb, Nut, Isis, Osiris, Set and Nephthys (all noted among the above-described plagues). Still, the Great Ennead was occasionally worshiped with a “plus-one,” a 10th deity, the great son of Isis and Osiris: Horus.

10. Against Pharaoh (and Everything Else)

The 10th and final plague struck at everything in a single stroke—from Pharaoh to commoner to rat, and any and all gods that represented them. It was a decisive blow for the nation, especially at a time when firstborn were all but revered. Exodus 12:30 shows that not a single Egyptian family was spared.

“For I will go through the land of Egypt in that night, and will smite all the first-born in the land of Egypt, both man and beast; and against all the gods of Egypt I will execute judgments: I am the Lord” (verse 12).

The pharaoh and his family were demigods to the Egyptians. Across the nation, they were revered as part god, part human, and the offspring of the gods themselves. Like Egypt’s countless gods, Pharaoh and his family were supposed to be untouchable to the plight of common mortals. With the final plague, the God of Israel struck down the final “god” family of Egypt, in a way that would be most crippling—more so than Pharaoh’s own death. Pharaoh’s most prized possession, his own son—the child-god, part of the Pantheon of “all-powerful” deities—was killed.

“And Pharaoh rose up in the night, he, and all his servants, and all the Egyptians; and there was a great cry in Egypt; for there was not a house where there was not one dead. And he called for Moses and Aaron by night and said: ‘Rise up, get you forth from among my people, both ye and the children of Israel; and go, serve the Lord, as ye have said. Take both your flocks and your herds, as ye have said, and be gone; and bless me also’” (verses 30-32).

Deliverance

Following the catastrophic final plague, the Israelites were finally freed. Egypt, its pharaoh, and its gods had been utterly humiliated, and the Egyptians “thrust” the Israelites out of the land. In fact, Pharaoh and his people were so desperate to get them out, they essentially paid the Israelites to leave, showering them with gifts. “[F]or they said: ‘We are all dead men’” (see Exodus 11:1-3; 12:33-36).

With the final plague complete, Israel joyously fleeing, and Egypt wallowing in dust and ashes, God’s plan was fulfilled. God had accomplished what He set out to do: “[T]he Egyptians shall know that I am the Lord, when I stretch forth My hand upon Egypt, and bring out the children of Israel from among them” (Exodus 7:5).

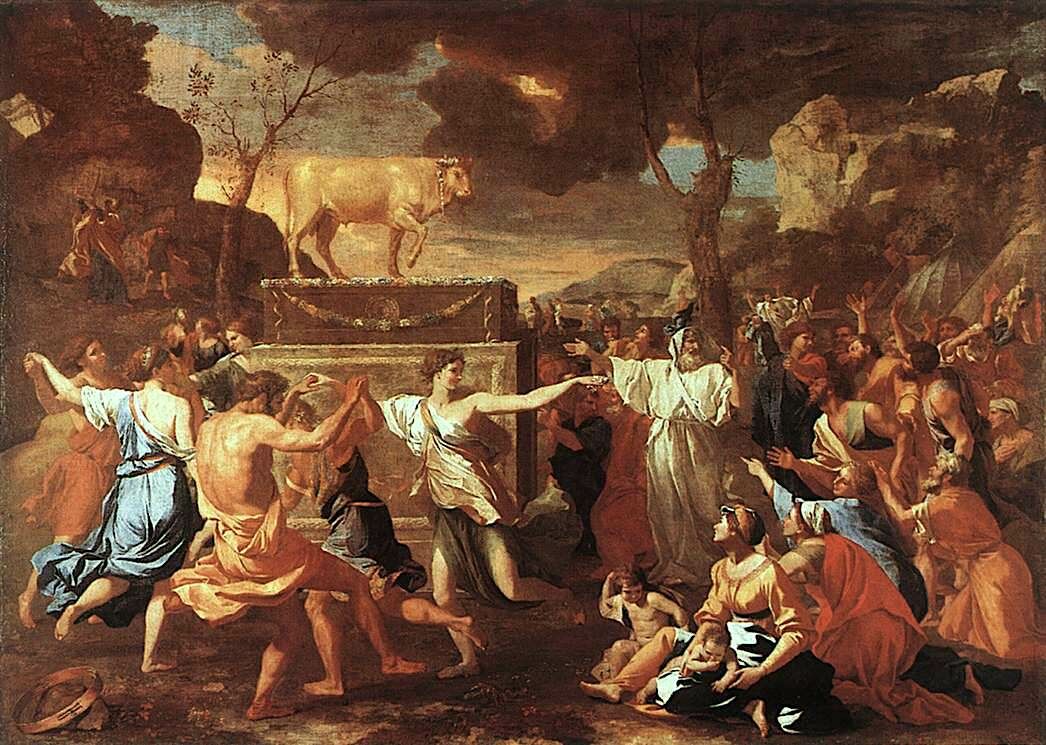

But bringing Israel out of Egypt was the easy part. What proved to be far more difficult was bringing Egypt out of Israel.

It wasn’t long after the Israelites crossed the Red Sea that the masses were pleading to return to Egypt and its gods. Encamped at the base of Mount Sinai, they erected a “golden calf” after the form of Hathor-Apis worship. Aaron proclaimed: “‘This is thy god, O Israel, which brought thee up out of the land of Egypt’” (Exodus 32:4).

What a powerful lesson for us about human nature! Despite the many miracles—despite sparing the land of Goshen—despite the utter humiliation of the Egyptian deities—despite the freedom of an enslaved population—despite agreeing to God’s covenant at Mount Sinai (many of the terms and conditions of this covenant directly forbade the Egyptian-style pagan practices)—the Israelites simply refused to come completely out of Egypt and obey the God of Israel. Forty years later, only two of the million-plus freed adults were allowed to enter the Promised Land (Exodus 12:37; Numbers 14:26-31).

The lessons of the 10 plagues hold true today. Stubborn human nature has not changed over the past 3,500 years. In many ways, we are like the ancient Israelites and the Egyptians. Even when faced with extreme adversity, human nature is determined to hold on to its own selfish, wicked ways and pursue its own evil ambitions. Like Pharaoh himself, we can find it hard to abandon our human will, even when it is exposed as corrupt.

Perhaps we no longer worship pot-bellied, hippo-headed, crocodile-tailed Nile gods. But as the Bible repeatedly states, an idol is anything we put above God—be it possessions, friends, family, even ourselves. The pursuit of material wealth and possessions is a god. In that respect, we can be just as pagan as the ancient world.

The moral of the story: God’s all-encompassing power—and the nothingness of man’s religions, technology and philosophy—is summed up on either side of the 10 plagues: “And God said unto Moses: ‘I am that I am …’” (Exodus 3:14); “[A]gainst all the gods of Egypt I will execute judgments: I am the Lord” (Exodus 12:12).

“I am the Lord thy God, who brought thee out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of bondage. Thou shalt have no other gods before Me” (Exodus 20:2-3).