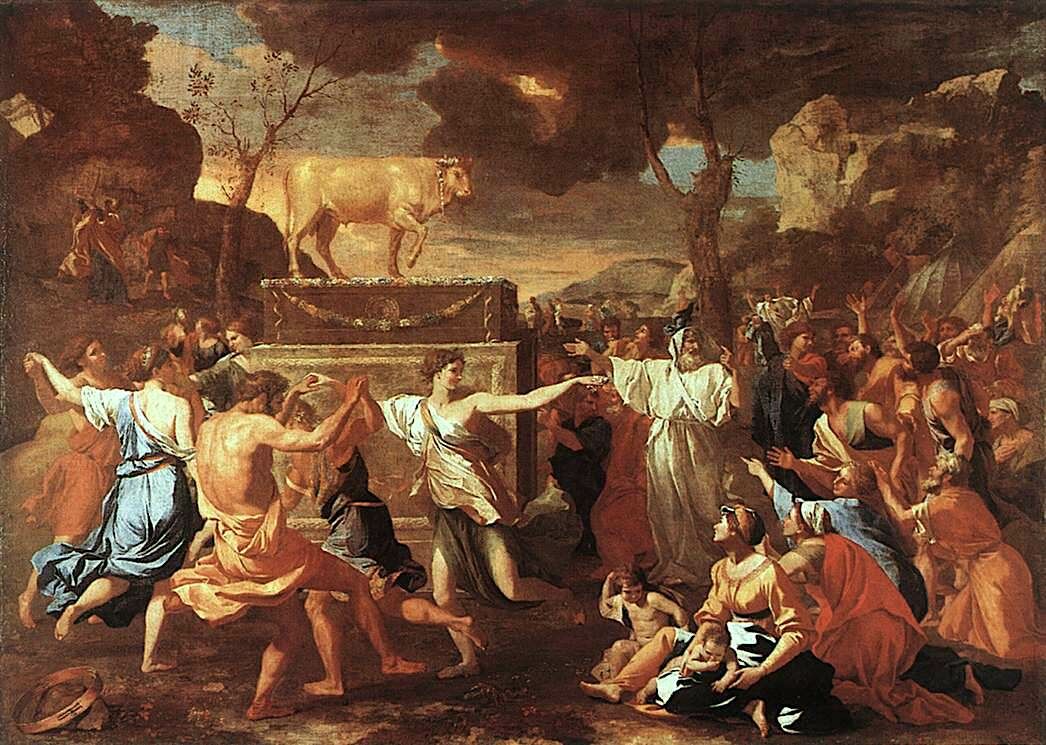

It’s one of the shocking turns in the biblical account: The Israelites had just been freed from Egypt, having witnessed a staggering series of plagues and miracles culminating in the parting of the Red Sea. Gathering at the base of Mount Sinai, they had heard the commandments delivered by the voice of God, and had covenanted to be His people and obey His laws (Exodus 24). But after Moses ascended the mount to receive the written tablets, the Israelites forged a golden calf and initiated hedonistic worship. Exodus 32:7-8:

And the Lord spoke unto Moses: ‘Go, get thee down; for thy people, that thou broughtest up out of the land of Egypt, have dealt corruptly; they have turned aside quickly out of the way which I commanded them; they have made them a molten calf, and have worshipped it, and have sacrificed unto it, and said: This is thy god, O Israel, which brought thee up out of the land of Egypt.’

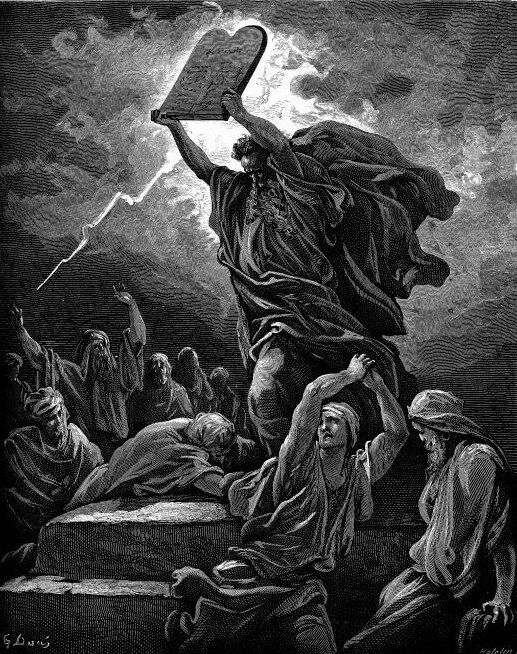

Moses pleaded for God’s mercy upon the people, and raced down the mountainside. “And it came to pass, as soon as he came nigh unto the camp, that he saw the calf, and the dancing …. And when Moses saw that the people were naked …” (verse 19, 25, King James Version). The shocked and furious Moses tore down the statue, and summarily had 3,000 revelers executed.

Many believe the Exodus account is mere myth. But what about this event? Some fascinating remains at the site of Serabit el-Khadim help shed light on this remarkable story.

Turquoise Miners, Peculiar Language

Serabit el-Khadim was a large Egyptian turquoise mine located in the southwest Sinai Peninsula. These mines were operated on the backs of Semitic workmen, particularly during the mid-second millennium b.c.e.—the same time period that, according to biblical chronology, the Israelites were in Egypt.

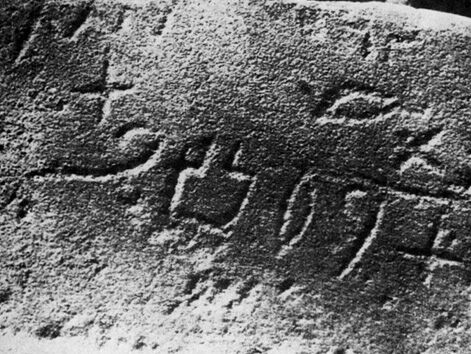

The site has provided some fascinating discoveries—one of which is a series of inscriptions known as “Proto-Sinaitic” (or “Proto-Canaanite”). These inscriptions date somewhere around the 15th century b.c.e. and appear to represent an evolving, new Semitic alphabet developed from Egyptian hieroglyphs. Prof. Douglas Petrovich names it “Old Hebrew,” identifying a number of words he believes to be of early Hebrew form and script-style. He has translated a handful of the approximately 40 inscriptions as follows:

- Sinai 115: “Six Levantines: Hebrews of Bethel, the Beloved.”

- Sinai 361: “Our bound servitude had lingered. Moses then provoked astonishment. It is a year of astonishment ….”

- Sinai 375a: “The Overseer of Minerals, Ahisamach.” (Ahisamach was the father of one of the chief Israelite craftsmen who oversaw the building of the tabernacle and ark: Exodus 31:6.)

- Sinai 376: “The house of the vineyard of Asenath and its innermost room are engraved ….” (Asenath was the name of Joseph’s wife: Genesis 41:45.)

As this is a very early form of script, there is an ongoing debate about the correct translations and general nature of the inscriptions—more can be read here.

Besides the intriguing inscriptions, one of the especially notable discoveries from this mine is the kind of worship that took place there.

Oblations to a Cow-Goddess

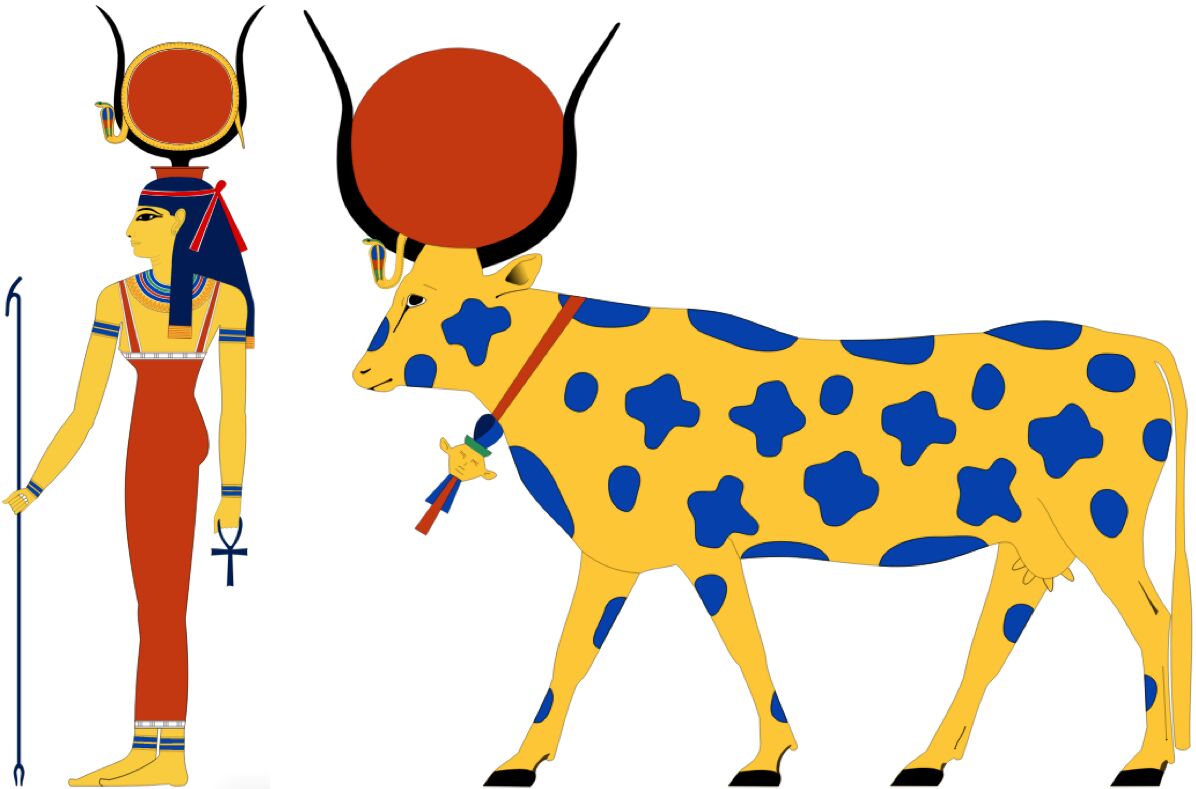

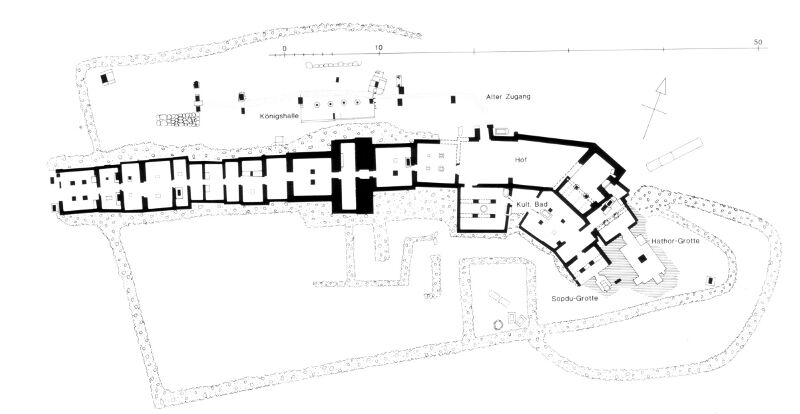

This otherwise-obscure Egyptian mine was unique, as it featured one of the most important temples of ancient Egypt. The 2,800-square-meter temple at the site is the largest in the Sinai Peninsula and the oldest example of an Egyptian temple hewn from rock. It was a place of worship to Hathor—the cow-goddess.

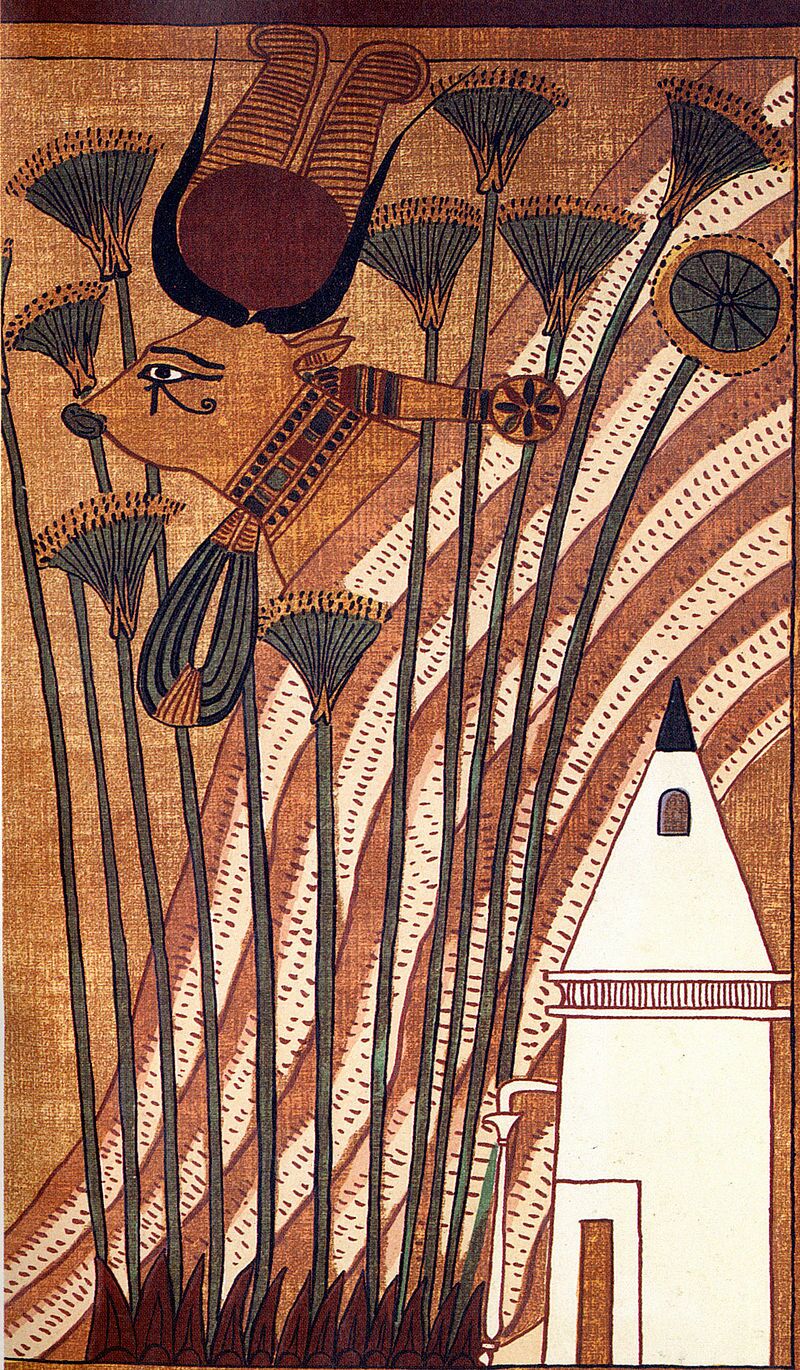

Hathor represented a number of different things to the Egyptians—dance, music, love, sexuality and maternity. She was typically depicted in two different ways: as a woman with a headdress of cow horns and a sun disk, or entirely as a cow. As a cow-goddess, she represented a maternal nature, and women desiring children would make offerings to her. She was also related by the Egyptians to the fertile land of Canaan. And she was regarded as the “Mistress of Turquoise,” a nod to the Serabit el-Khadim mine.

All of this becomes even more intriguing when considering the location of this Hathor temple-mine: barely 70 kilometers northwest of the traditional location for Mount Sinai (Jebel Mousa; one scholar—Lina Eckenstein—goes so far as to identify Serabit el-Khadim as Mount Sinai itself). At least, it was along the route to the mountain.

It is notable that the Egyptians had to keep an armed guard over the mines to protect them from raiding “Bedouins” in the territory. The Bible relates that as the Israelites set foot into this land, they were set upon by the nomadic Amalekites (whom they defeated—Exodus 17).

Given the proximity of the Hathor temple to Mount Sinai, we can perhaps start to get a clearer—albeit still speculative—context for the Exodus 32 account.

We can speculate that as the freed Israelites made their way from Egypt into the Sinai, many were familiar with the territory, having slaved in the turquoise mines. Likely, many had worshiped Hathor—forced, indoctrinated or otherwise. Perhaps some even began to ascribe their freedom to this “nearby” cow-deity.

The type of revelry in Exodus 32 matches the worship of Hathor. The Israelites are described as worshiping in a hedonistic manner, “playing,” singing and dancing in the nude (verses 6, 18-19, 25). Hathor was the “mistress” of singing, dancing and drunkenness—revelers at her festivals would attempt to reach a climax of “religious ecstasy” and “altered conscience” in order to commune with the spirit world. Some scholars also believe that worshipers engaged in sexual relations in order to worship her. Egyptian wall-art exists of instrumentalists and naked dancers prancing, in allusion to the goddess (e.g. the tomb of Nebamun, circa 14th century b.c.e.).

Perhaps an Israelite affinity for Hathor is further indicated by another Semitic Serabit el-Khadim inscription (Petrovich): Sinai 349, “He sought occasion to cut away to barrenness our great number, our swelling without measure. They yearned for Hathor ….”

Divine Judgment

The outcome of the Israelites’ relapse into idolatry was quick and clear. God intended to wipe out the Israelites wholesale and start a new nation afresh with Moses. Thanks to Moses’s intercession, God spared them. Still, 3,000 revelers were executed. And Moses’s wrath pushed him beyond the breaking point: He smashed the stone tablets upon which God had engraved His commandments (Exodus 32: 19).

What Moses did next was peculiar: He burned the golden calf completely, grinding the molten gold into the Israelites’ water source (verse 20). Why a burning? This would have had great significance to those familiar with ancient Egyptian customs. The worst form of punishment for a criminal in Egypt was to be burned. This was because of Egypt’s preoccupation with preserving, mummifying the creature or human form for the afterlife. Burning was a terrifying punishment, because it ensured that nothing was left to enter the afterlife. Even though the calf was an inanimate object, the burning may have been deeply symbolic to the Israelites—issuing the highest form of Egyptian “punishment” for this pagan goddess.

It is important to remember the context of the books of Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. There are many laws and stories that seem strange and unusual: forbidding “marring the corners of the beard”; forbidding mixing a “kid in its mother’s milk”; building a golden calf. Many events, actions and reactions appear peculiar. But they are all in the context of the Israelites leaving Egypt. This people, soaked in paganism, was emerging from a heathen society, learning new laws and a new way of life.

The 10 plagues—rivers of blood, legions of frogs, thick darkness, etc—were all an answer to specific, trusted Egyptian deities. Unusual laws of dress and grooming (e.g. Leviticus 19) were specified in answer to traditional Egyptian methods of dress and grooming. As with sacrificial laws, familial laws, etc.

Unfortunately, this basic and overarching premise is overlooked by some researchers who seek to deny historical corroboration for the Exodus account. One Haaretz archaeological piece titled “For You Were (Not) Slaves in Egypt” states the glaring “problem” that there is no evidence of Yahweh-worshiping slaves in Egypt. But the Bible clearly states that the Israelites weren’t free to worship in Egypt—and that “by my name Yahweh was I not known to them” (Exodus 6:3; 3:13-15). This was the whole point of the Exodus—to free the Israelites to be able to worship God (verse 7; 7:16). Put bluntly, the Israelites in Egypt would be better described as bovine-worshiping, Sabbath-breaking, non-kosher-eating, indoctrinated, threadbare slaves attempting to survive, to spare their newborns from state-mandated infanticide, crying out to some kind of divine power—any kind—to free them.

As the Bible relates, God heard their cries and set them free, displaying a whole host of miracles, proof of His divine power, and a new, right way of worship, of life. Those willing to change and obey lived; those who stubbornly refused, perished. Ultimately, by the time the Israelites entered the Promised Land, only Joshua, Caleb and those under the age of 20 at the time of the Exodus were still alive.

The story of the golden calf—and the Exodus in general—illustrates an important point. The journey out of Egypt did not end with the Red Sea miracle. It did not end with the covenant at Mount Sinai. It did not even end with the conquest of Canaan, some 40 years later. These were only elements of a much more arduous journey: an Exodus from a deep-seated “Egyptian” state of mind. A journey that each of us, in his or her own personal situation, is still on to this day.