Just how old is Jerusalem?

Archaeology has corroborated numerous biblical events in the city, including the construction of David’s palace in the 10th century b.c.e., Solomon’s expansion, Uzziah’s tower-building, Hezekiah’s siege preparations, Josiah’s royal administration, Jeremiah’s persecution, Babylon’s destruction, and Nehemiah’s rebuilding in the fifth century b.c.e. Archaeology has confirmed at least six biblical kings of Judah and 10 other royal and priestly personalities.

But what about Jerusalem before David? The Bible contains many references to the city prior to its establishment as the nation’s capital. What does the archaeological record tell us?

Beginnings

Today, Jerusalem and its suburbs constitute the largest city in Israel. But ancient Jerusalem was much smaller. Before King Solomon’s expansions, Jerusalem consisted of roughly only 12 acres centered on a small, crescent-shaped ridge later known as Mount Zion. The city was dependent on the gushing waters of the Gihon Spring.

The earliest remains discovered in Jerusalem are scattered, piecemeal potsherds found embedded in cracks in the bedrock. The potsherds have been dated as far back as around 4000 b.c.e. These artifacts show that Jerusalem was inhabited early in human history, but not that it was inhabited continuously. Archaeology indicates that Jerusalem’s first city wall was not built until around the 1800s b.c.e.

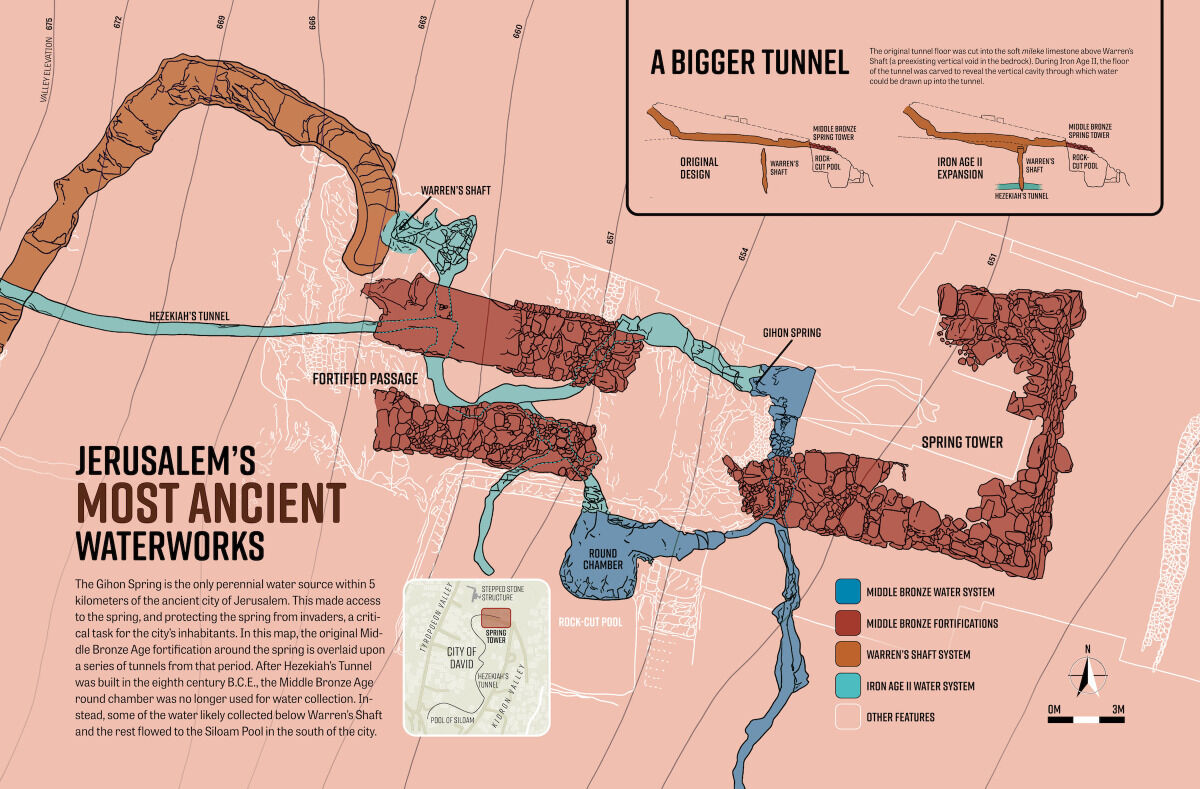

Archaeologists including Kathleen Kenyon, Eli Shukron and Ronny Reich have unearthed walls, towers, tunnels and a pool relating to this first fortification, located around the lower City of David near the Gihon Spring. These structures were dated by pottery, parallel architectural style, and stratigraphy.

In 2010, Reich and Shukron published the findings of their excavation of a large tower built around the Gihon Spring, which they dated to this period, known as Middle Bronze ii. The “Spring Citadel” was built with unworked boulders as large as 2 by 2 meters, and constructed in a style known as “cyclopean masonry.” This is a building technique that uses massive, unworked boulders: The ancient Greeks attributed such architecture to the work of the mythical, giant Cyclopes race. Besides these boulders, the Gihon “Spring Citadel” walls were up to 7 meters wide at their foundations. Walls of this size were not built again in Israel until the reign of King Herod the Great, about 1,800 years later.

In addition to this large ancient structure, a number of inscriptions have been discovered indicating Jerusalem was well established at this time. The Egyptian Execration Texts, dating to the 19th to 18th centuries b.c.e., pronounce curses on various enemies and name several cities in Canaan, including Rushalim. Epigraphers believe this is a reference to Jerusalem (pronounced Yirushalaim in Hebrew). The reference to Rushalim at the end of the strong Egyptian Twelfth Dynasty (circa 2000–1800 b.c.e.) attests to the importance of the early city. This seems peculiar, however, given its small area and estimated population of around 500 inhabitants. Why would the powerful and mighty Egyptian empire pay it any attention at all?

The answer may well be in the identity of Jerusalem’s first-described king—Melchizedek.

King of Righteousness

Melchizedek is the first king of Jerusalem mentioned in the Bible, and the dating of Jerusalem’s earliest construction parallels the biblical time frame for this individual.

Genesis 14 records that following Abraham’s defeat of an Assyrian alliance, he was commended and blessed by “Melchizedek king of Salem” (verse 18). The city name Salem is the earliest biblical form of the name Jerusalem. (Psalm 76:3 identifies Salem as Zion, another name for Jerusalem.)

The name “Melchizedek” means “king of righteousness.” This individual was both king of Jerusalem and “priest of God the Most High” (Genesis 14:18). Genesis 14 states that Abraham paid tithes to this remarkable king-priest of Jerusalem. There is a New Testament statement about Abraham looking toward a Jerusalem “which hath foundations, whose builder and maker is God” (Hebrews 11:10; King James Version). Evidence from both the scriptural account and archaeological period indicates that Melchizedek was the founder of the Holy City.

This is further suggested in the name of the city. Salem means peace (also, completeness). The alternate form, Jerusalem, means “city (or foundation) of peace.” Perhaps that name was only taken on after these “foundations” were laid, during the 1800s b.c.e.

Rabbi Jehiel Heilprin’s Seder HaDoroth, published in 1769, states outright that Melchizedek was the first to complete a wall around Jerusalem. This was written two centuries before any corroborating archaeological evidence was discovered.

Much of Jerusalem’s original construction revolved around its all-important water source, the Gihon Spring. The Gihon Spring is mentioned several times in the Bible, and has deep biblical symbolism.

A very early pool and channel are connected to the Gihon. Archaeologists have dated this “upper pool,” or “old pool,” to the same Middle Bronze period (of Abraham and Melchizedek). The pool’s construction appears to be mentioned by the Prophet Isaiah in a condemnation of King Hezekiah and the people of Judah for their rebellion against God: “Ye made also a ditch between the two walls for the water of the old pool: but ye have not looked unto the maker thereof, neither had respect unto him that fashioned it long ago” (Isaiah 22:11; kjv).

Isaiah alludes to God as the ultimate “maker” of this pool. But through whom did God make it? Was it Melchizedek, the mysterious king and priest of Jerusalem?

Canaanite Fortress

According to biblical chronology, about 400 years elapsed between this meeting between Melchizedek and Abraham and the arrival of the Israelites in the Promised Land. During this period, Jerusalem was inhabited by a Canaanite tribe called the Jebusites, who called the city “Jebus” (Judges 19:10).

The Canaanites included a number of tribes, mostly the Amurru (biblical Amorites) and the Hurrians (biblical Horites). The earliest certain mention of the name Canaan is found on the statue of Idrimi, king of Alalakh. Discovered in modern-day Syria, this statue dates to the 16th century b.c.e. However, other possible mentions of the name have been dated as far back as 2500 b.c.e.

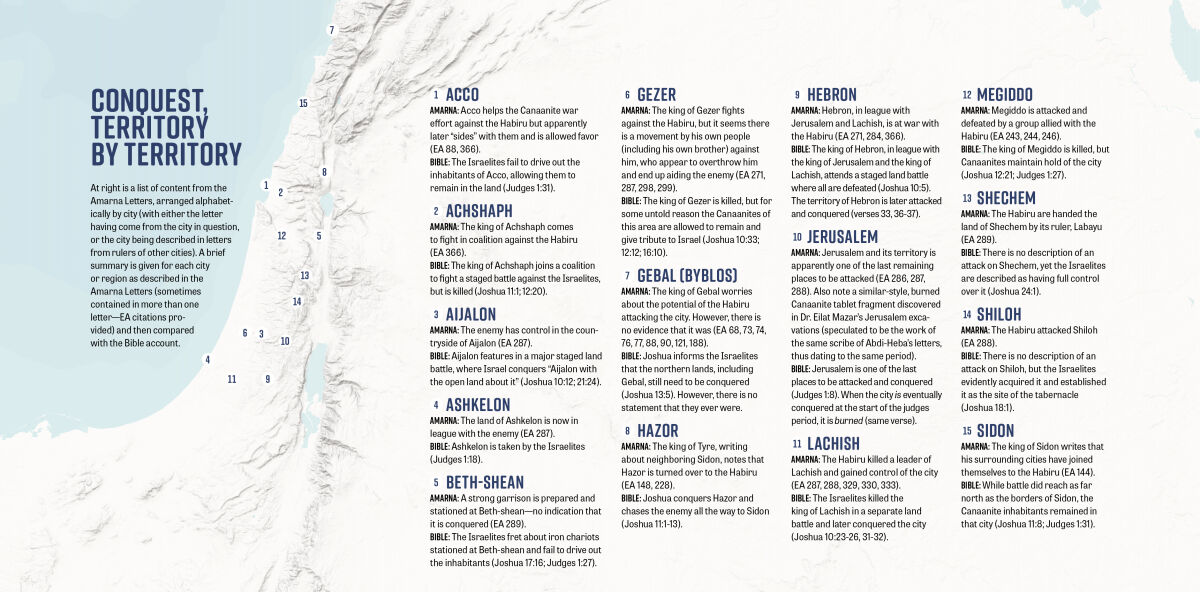

Throughout the Middle-Late Bronze Age, Egypt controlled large sections of Canaan. During the 16th to 15th centuries b.c.e. especially, the Egyptians exerted strong military control over the land (including Jerusalem), and the Canaanites were their subjects. The end of this period is illuminated by the remarkable Amarna letters.

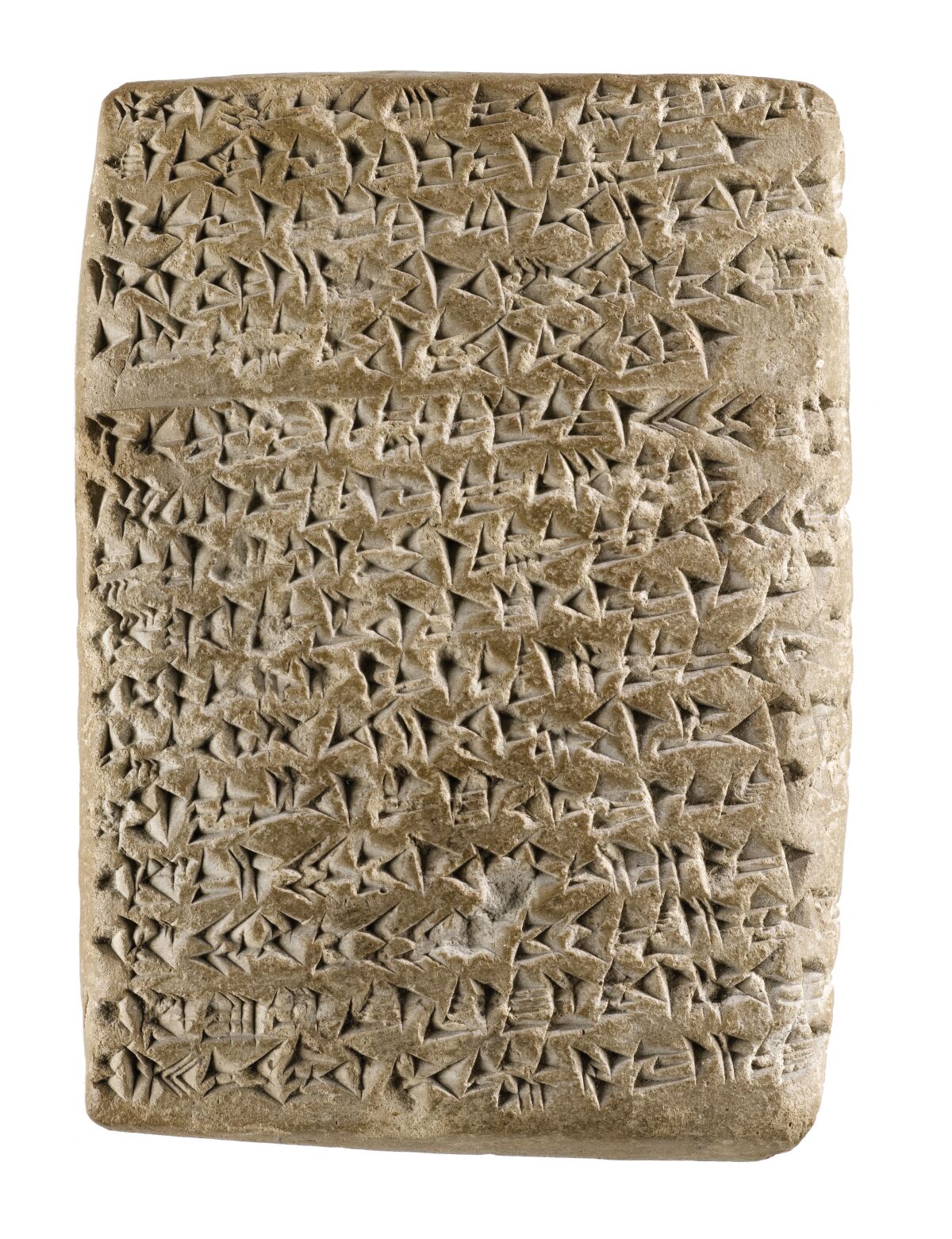

The Amarna letters are a trove of nearly 400 cuneiform clay tablet documents sent from Canaanite cities to the Egyptian pharaoh. Found during the late 1800s in the Egyptian city of Amarna, the letters have been dated to the decades prior to the destruction of the city, in the mid-14th century b.c.e. Many of these letters carry startling messages, including correspondence from the Canaanite king of Jerusalem.

When the Amarna letters were written, the land of Canaan was being overrun by an invading group of nomadic people identified in the letters as the Habiru (alternatively, Hapiru, ‘Apiru and Habiri). Desperate for help, the Canaanites sent urgent dispatches to Egypt. The repetition of the pleas indicates the Egyptians sent little help, if any.

Many who have studied the Amarna letters note the obvious linguistic similarities between Habiru and Hebrew. At this point in the biblical record, the collective term “Hebrews” is used more often than “Israelites.” The dating of the Habiru invasion, in the decades following 1400 b.c.e., matches with the biblical chronology of the Hebrews’ arrival in the Promised Land. One tablet even contains a possible mention of the tribe of Judah. While the identity of the Habiru remains a topic of hot debate, one of the most convincing associations of these people with the biblical Hebrews is the account of what they did. These people took possession of huge swathes of land in Canaan.

The desperation of the Canaanites is evident in the Amarna letters, and the correspondence between the leader of Jerusalem and the king of Egypt is a case in point. Here are some excerpts from two letters sent by Abdi-Heba, mayor of Jerusalem (Urushalim), to Egypt’s pharaoh.

Amarna letter EA286: “Message of Abdi-Heba, your servant …. May the king [Egypt’s pharaoh] provide for his land! All the lands of the king, my lord, have deserted …. Lost are all the mayors; there is not a mayor remaining to the king, my lord.The king has no lands. That Habiru has plundered all the lands of the king. If there are archers this year, the lands of the king, my lord, will remain ….”

Amarna letter EA288: “May the king give thought to his land; the land of the king is lost. All of it has attacked me…. I am situated like a ship in the midst of the sea …. [N]ow the Habiru have taken the very cities of the king. Not a single mayor remains to the king, my lord; all are lost.”

The letters indicate that much of the land had already fallen to the Habiru. This is consistent with the biblical text; the Bible does not describe a conquest of Jerusalem until the start of the book of Judges, after the account of Joshua’s death. This could explain why, as Abdi-Heba fearfully declared, “all” the surrounding lands of Canaan had already fallen, yet Jerusalem remained—temporarily.

During excavations in Jerusalem in 2010, archaeologist Eilat Mazar uncovered a cuneiform tablet fragment in the same style and dating to around the same time as the Amarna letters. The tablet is the oldest piece of writing ever discovered in Jerusalem. Petrographic analysis of the tablet found that it was made from local Jerusalem clay. Its partial inscription is difficult to translate, but Dr. Mazar speculates that the tablet may have been archival correspondence, of a similar nature to the Amarna letters. Notably, the fragment is blackened by fire. This may be explained by Judges 1:8, which states that when the people of Judah eventually besieged Jerusalem, they “set the city on fire.”

We do not know what happened to Abdi-Heba, the Canaanite ruler of Jerusalem. Based on the Amarna letters, some speculate that he may have eventually reconciled with the Habiru. This too would fit with the biblical record; several scriptures show that after the initial destruction of Jerusalem, the Jebusites continued to occupy the city, dwelling within Israelite territory.

One final note about Abdi-Heba. In one of his letters to the pharaoh, he makes an interesting statement: “As the king [pharaoh] has placed his name in Jerusalem forever, he cannot abandon it” (EA287). This phraseology is found repeatedly in the Bible: God uses this phrase to describe His relationship with Jerusalem. “I have chosen Jerusalem, that My name might be there …” (2 Chronicles 6:6); “[I]n Jerusalem, which I have chosen out of all the tribes of Israel, will I put My name for ever” (2 Chronicles 33:7). This tablet, then, confirms the historical use of such biblical language.

Of course, the name of a pharaoh no longer has any “place” or lasting memory in the Holy City—but the name of God certainly does!

A Jebusite Thorn

Following the initial Hebrew destruction of Jerusalem in the 14th century b.c.e., the Jebusites continued to inhabit the city, living alongside the Israelite tribe of Benjamin (Judges 1:21). They remained in place for some 350 years, and by the late 11th century were still safely ensconced within the fortress of Jebus, one of several Canaanite thorns remaining within the kingdom of Israel (Judges 2:3). Evidence of the Canaanite presence at this time has been proved through archaeology.

The Bible records that David became king just before 1000 b.c.e. For the first seven years he ruled from Hebron, but his ultimate ambition was to unite the 12 tribes and rule from a new capital: the symbolically significant Jerusalem. The city was located in a perfect diplomatic position, on the border between the tribes of Judah and Benjamin; it was strategically situated atop steep Mount Zion; and the Gihon Spring provided a reliable water source. Most significantly, the city’s history, extending back to Melchizedek and Abraham (and potentially even further), would have given it distinct status in the minds of the people.

The belligerent Jebusites taunted David, telling him that the steep approaches and strength of the fortress meant even the “blind and the lame” could defend the city from him. David offered a military captainship to whichever of his men could enter the city through a “gutter” to overcome the Jebusites (2 Samuel 5:6-9). Joab led a squad of troops into the city through this water tunnel, overpowered certain of the Jebusites, and opened the gates to David and the rest of his men.

During Dr. Mazar’s 2008 excavations in the City of David, her team stumbled upon a narrow tunnel dating to the 10th century b.c.e. The tunnel, though still blocked by debris, is at least 50 meters (160 feet) long and had been cut and walled through a natural crack in the bedrock, barely allowing passage for a man to squeeze through. It may have originally been used to channel water, and thus has been identified by Mazar as a candidate for the conduit through which Joab and his men infiltrated Jebus.

The Jebusites were not all killed, however. A peculiar Bible passage in 2 Samuel 24 shows that at the end of David’s reign, a Jebusite called Araunah owned some land (including a threshingfloor) just outside the northern walls of the City of David.

Evidently, King David allowed him to live, work and own property in the vicinity of Jerusalem. Who was this Jebusite? Araunah is not a name; ancient texts show that it is a Near Eastern title meaning lord. Araunah may have actually been the former Jebusite king of Jerusalem, as is indicated by verse 23: “All this did Araunah the king give unto the king.” This account records the moment King David purchased Araunah’s land, upon which the first temple would be built.

City of David

At the start of the 10th century b.c.e., Jerusalem—also called Salem, Zion, Jebus and Moriah—got a new name: the City of David (2 Samuel 5:9). King David’s arrival in the city marked the beginning of a new era of growth and development.

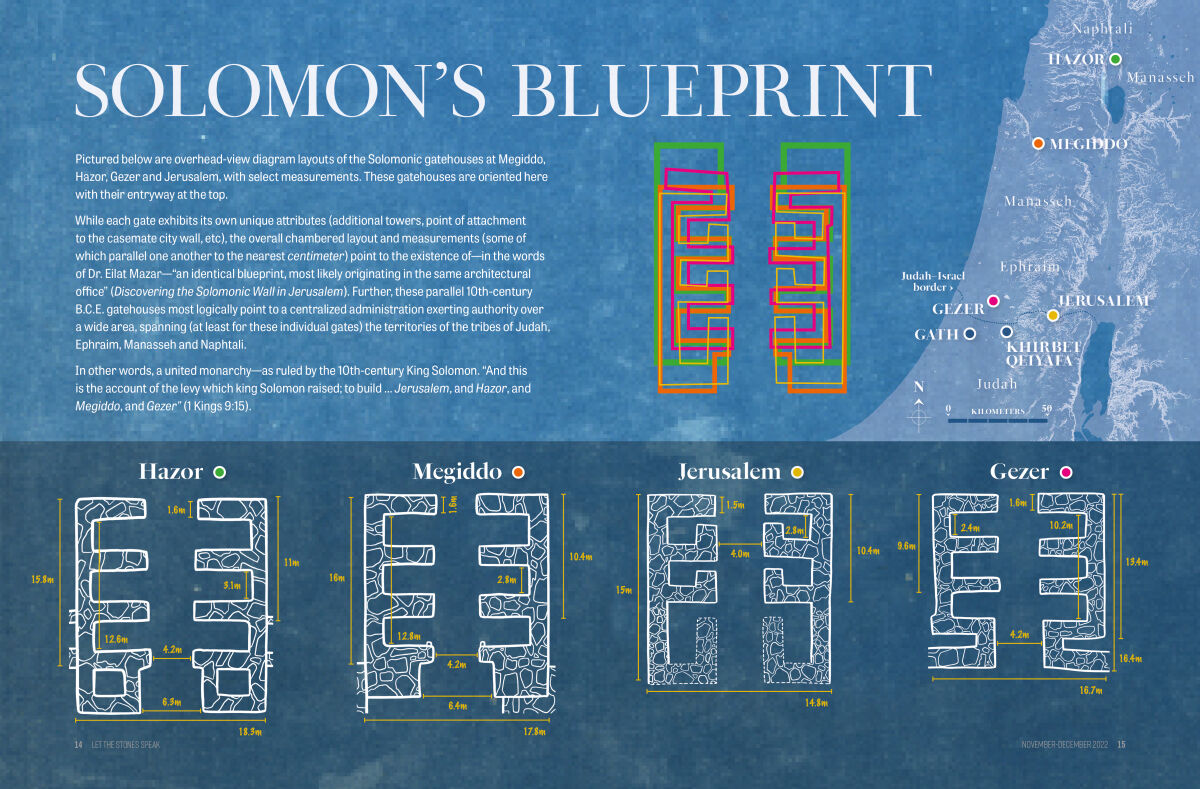

Over the past 30 years, archaeologists have uncovered a wealth of evidence testifying to Jerusalem’s size and importance during the 10th century b.c.e. This includes a massive, elaborate palatial building (paralleling the biblical account of David’s palace—verses 11, 17); large, fortified walls showing Jerusalem’s northward expansion under King Solomon (1 Kings 3:1); and a massive Solomonic gatehouse similar to those unearthed at Hazor, Megiddo and Gezer—three chief cities identified with Jerusalem as part of Solomon’s nationwide building program (1 Kings 9:15).

Beginning with King David, Jerusalem became a new, expanded city, but at its throbbing heart was the old city: the gushing Gihon Spring and the gigantic original fortifications. Though this city is mostly known from the First Temple period onward, its illustrious history extends much further back.

Israelis often mention their “3,000-year connection” with their capital. That connection actually goes back some 4,000 years, to the days of Abraham and Melchizedek. This was truly a “city with foundations,” in which God has “placed His name forever.”

This is Israel’s capital.