“And Miriam and Aaron spake against Moses because of the Ethiopian woman whom he had married: for he had married an Ethiopian woman” (Numbers 12:1; King James Version). It’s a peculiar passage—and provides only the slightest hint at what is an incredible backstory of military prowess and romance, described in accounts of classical antiquity.

Moses’s 120-year life is divided up into three primary parts: 40 years as a prince in Egypt, 40 years as a shepherd in Midian, and 40 years as the leader of Israel. The Bible, of course, primarily describes the last part of his life. There’s even a significant description of Moses in Midian (Exodus 2-4). Only a handful of verses describe his early years in the Egyptian courts. But of those, we do get a few clues that, paired with other historical accounts, reveal a fascinating and dynamic period of Moses’s life in Egypt.

You’ve heard of Moses, leader of Israel. What about the story of Moses, “conqueror of Ethiopia”—and the surrounding archaeological evidence?

Moses, Military General

The first-century c.e. historian Flavius Josephus is one of the most prominent of the ancient Jewish historians. He is particularly well known for his eyewitness account of the fall of Jerusalem to the Romans in c.e. 70—but he is also known for his detailed compendium of history from Adam to his own lifetime, titled Antiquities of the Jews.

In Antiquities of the Jews, Josephus devoted an entire (albeit short) chapter to the subject of Moses’s years as a prince in Egypt, titled “How Moses Made War With the Ethiopians.” He described the Ethiopians (referred to as “Cushites/Kush” in the Bible and other ancient literature) as enemies of the Egyptians at the time of Moses who successfully warred against them, making inroads into Egypt as far north as Memphis and even to the Mediterranean Sea. “The Egyptians, under this sad oppression, betook themselves to their oracles and prophecies; and when God had given them this counsel, to make use of Moses the Hebrew, and take his assistance, the king commanded his daughter to produce him, that he might be the general of their army” (Antiquities, 2.10.1).

Josephus’s account proceeds to describe Moses’s “sagacity” in leading the Egyptian forces against the Ethiopians, not by way of the Nile River, as expected, but through the dangerous desert terrain—a region infested with deadly snakes that “ascend out of the ground unseen, and also fly in the air, and so come upon men unawares.” Josephus described Moses’s scheme of bringing snake-eating “ibes” (ibis birds) with the army in cages: “As soon, therefore, as Moses was come to the land which was the breeder of these serpents, he let loose the ibes, and by their means repelled the serpentine kind, and used them for his assistants before the army came upon that ground.” Josephus continued:

When he had therefore proceeded thus on his journey, he came upon the Ethiopians before they expected him; and, joining battle with them, he beat them, and deprived them of the hopes they had of success against the Egyptians, and went on in overthrowing their cities, and indeed made a great slaughter of these Ethiopians.

So defeated were the Ethiopians that they were “in danger of being reduced to slavery,” Josephus wrote. The Ethiopian army was forced to withdraw as far back as the royal city of Saba/Meroe, a heavily fortified, almost island-like location surrounded by rivers. As Moses wondered what to do next, some remarkable drama occurred. Josephus wrote:

[W]hile Moses was uneasy at the army’s lying idle, (for the enemies durst not come to a battle,) this accident happened:

Tharbis was the daughter of the king of the Ethiopians: She happened to see Moses as he led the army near the walls, and fought with great courage; and admiring the subtilty of his undertakings, and believing him to be the author of the Egyptians’ success … and to be the occasion of the great danger the Ethiopians were in, when they had before boasted of their great achievements, she fell deeply in love with him; and upon the prevalency of that passion, sent to him the most faithful of all her servants to discourse with him about their marriage.

“He thereupon accepted the offer, on condition she would procure the delivering up of the city; and gave her the assurance of an oath to take her to his wife; and that when he had once taken possession of the city, he would not break his oath to her. No sooner was the agreement made, but it took effect immediately; and when Moses had cut off the Ethiopians, he gave thanks to God, and consummated his marriage, and led the Egyptians back to their own land” (ibid). It’s a remarkable story, that Josephus linked to the account of Moses’s biblical Ethiopian wife. But are there any corroborating accounts?

Other Classical Sources

The primary source for material for Josephus’s Antiquities, of course, was the Holy Scriptures themselves. But also available to Josephus were an untold number of ancient works preserving various traditions, many of which he referenced and quoted from but have since been lost to time and disasters. (Perhaps the most notable example of such was the fire of Alexandria, which destroyed the Egyptian city library—arguably the most significant and largest library of the ancient world, containing as many as half a million precious scrolls.) For Josephus to have recorded what he did, and in such detail, this tradition evidently came from some earlier known extra-biblical source available at the time.

A similar account can be found among the works of the fourth-century c.e. historian Eusebius of Caesarea, who quoted the (now lost) work Concerning the Jews by third-century b.c.e. Jewish historian Artapanus. Artapanus’s account contains additional details, and it is possible that Josephus drew from it for his Antiquities. But it seems more likely, from the separate details in each account, that both drew from an even earlier, wider body of source material. Eusebius related some of Artapanus’s words as follows:

But Moses with about a hundred thousand of the husbandmen came to the so-called Nome of Hermopolis, and there encamped; and sent generals to preoccupy the country [of the Ethiopians], who gained remarkable successes in their battles. … [T]he people of Heliopolis say that this war went on for 10 years. So Moses, because of the greatness of his army, built a city in this place, and therein consecrated the ibis, because this bird kills the animals that are noxious to man.

“Thus then the Aethiopians, though they were enemies, [eventually] became so fond of Moses that they even learned from him the custom of circumcision: and not they only, but also all the priests” (Præparatio Evangelica, Book 9, Chapter 27). It is noteworthy that the fifth-century b.c.e. Greek historian Herodotus also affirmed that the Ethiopians learned circumcision from an Egyptian source.

The second-century c.e. Bishop Irenaeus wrote the following about the account: “Josephus says, that when Moses was nourished in the palace, he was appointed general of the army against the Ethiopians, and conquered them, when he married that king’s daughter; because, out of her affection for him, she delivered the city up to him” (The Fragments of Irenaeus). Hints of different elements of the story can be found in other pre-Josephus sources—for example, the first-century b.c.e. Greek historian Strabo wrote of the “island”-city Meroë, surrounded by the rivers Josephus described; and the early first-century Roman historian Pliny the Elder wrote of ibises being used by the Egyptians against snakes (“The Egyptians invoked them against the serpents;” The Natural History, 10.40).

Herodotus wrote about the same: Immense quantities of peculiar serpents that he himself witnessed on the border of Egypt, that by Semitic tradition were preyed on by ibises and revered for such by the Egyptians. “I saw bones of serpents and spines in quantity so great that it is impossible to make report of the number …. [T]he story goes that at the beginning of spring … the birds called ibises meet them at the entrance of this country and do not suffer the serpents to go by but kill them. On account of this deed it is (say the Arabians) that the ibis has come to be greatly honored by the Egyptians, and the Egyptians also agree that it is for this reason that they honor these birds” (Histories, 2.75.1-4).

It is possible that these snakes, of which Josephus described “ascend out of the ground unseen, and also fly in the air, and so come upon men unawares,” are the horned viper (Cerastes cerastes). This is a venomous snake, notable for its horns and ability to “sink” into sand—making itself virtually invisible in order to “fly” out and strike at unwitting prey. They are present in this southern border region of Egypt, and feature often in Egyptian inscriptions as a hieroglyphic symbol.

Summarizing Moses as a military leader, the second-century c.e. bishop and philosopher Clement of Alexandria wrote: “Our Moses then is a prophet, a legislator, skilled in military tactics and strategy. … Tactics belong to military command, and the ability to command an army is among the attributes of kingly rule” (Stromata, Book 1, Chapter 24).

As for the Bible?

Many have questioned the reference in Numbers 12:1 to Moses’s marriage to a Cushite—for example, if this meant Moses endorsed polygamy (since earlier chapters mention his marriage to a Midianite), something repeatedly spoken against throughout the Bible. Also, that it would constitute marriage outside of the race and culture of the Israelites. But the above accounts explain that this marriage was clearly a “pre-conversion” union that had already happened while Moses was a prince in Egypt.

Interestingly, though this English verse uses the word married twice, that is not the actual Hebrew word used; it is simply “taken” or “fetched.” As in the Young’s Literal Translation: “And Miriam speaketh—Aaron also—against Moses concerning the circumstance of the Cushite woman whom he had taken: for a Cushite woman he had taken.” (Notice the past tense as well.)

The Bible relates that at 40 years old, the prince fled for his life alone to Midian from Egypt, remaining there for 40 years and marrying a daughter of Reuel, named Zipporah. Zipporah had separated from Moses after a serious dispute while on his journey back into Egypt (Exodus 4:24-26). She rejoined him partway into the sojourn (Exodus 18:1-6, although this may have been only temporarily). Both marriages, in fact, occurred “pre-conversion.” And based on the way it suddenly appears in the biblical account: By the time of Numbers 12, it may be that Moses had only then “fetched” his Cushite wife out of her homeland to join the departed Israelites outside of Egypt.

After all, classical accounts indicate the young Moses’s Ethiopian wife remained in her land after their union. The 12th-century c.e. author Petrus Comester described Moses’s wife Tharbis choosing to remain in Ethiopia, keeping Moses’s ring that he gave her (an anecdote preserved in Sir Walter Raleigh’s The History of the World, 1614, Vol. 1, 3:4). The 12th-century Jewish Targum Yerushalmi (Targum Pseudo-Jonathan) explained the reason that she remained in her native land was because she was of the royal family: “And Miriam and Aaron spake against Moses words that were not becoming with respect to the Cushite … whom [Moses] had sent away, because they had given him the queen of Kush … observe, the Cushite wife was not Zipporah, the [other Midianite] wife of Moses, but a certain Cushite” (Numbers 12; the third-century b.c.e. Septuagint translation of Numbers 12:1 likewise makes this nationality clear).

While Numbers 12 is the primary biblical passage, there are other clues to Moses’s deeds as prince of Egypt elsewhere in the Bible. Notably, in the New Testament: In the first-century message of Stephen, he gives a brief summary of the time of Abraham to Solomon (Acts 7). Of Moses’s 40 initial years as prince of Egypt, he says: “Moses was taught all the wisdom of the Egyptians, and he was powerful in both speech and action” (verse 22; New Living Translation—the Greek word for “powerful” is the basis for the English word dynamite). Evidently Moses had accomplished some kind of “powerful” feats that were renowned in Egypt during the first third of his life. What were they? Stephen doesn’t say—but Josephus and others of the first century attest to the prevalence of such traditions most significantly surrounding Ethiopia, or Kush.

And perhaps this special Ethiopian connection with Moses and the Israelites could help explain why the later Queen of Sheba—traditionally held to be Queen of Ethiopia (Saba/Meroe)—took such a personal interest in visiting King Solomon in the first place; the reason why her nation sent such an enormous train of gifts (1 Kings 10; Psalm 68:30-32). After all, Sheba—Saba—was the name of the very territory cited by Josephus as being conquered by Moses, and from which he took his wife.

But besides the literary accounts, is there any archaeological evidence for such a conquest?

Kushite Domination of Egypt

The early polity of Kush is known as the “Kingdom of Kerma.” (The people are also variously named Kushites and Nubians. It is important to note that the Greek references to “Ethiopia,” such as by Josephus and the Septuagint, include the territory of Sudan, up to the border of Egypt.) The kingdom of Kerma was on the scene beginning around the mid-to-late third-millennium b.c.e. and reached its “peak” in its last phase at the start of the second millennium, between 1700–1500 b.c.e., swallowing up another neighboring kingdom within the modern territory of Sudan and then setting its sights on Egypt.

Still, there was no evidence for any significant initial Kushite defeat of mighty Egypt as described by Josephus, let alone during the 16th century b.c.e. period in question—that is, until 2003.

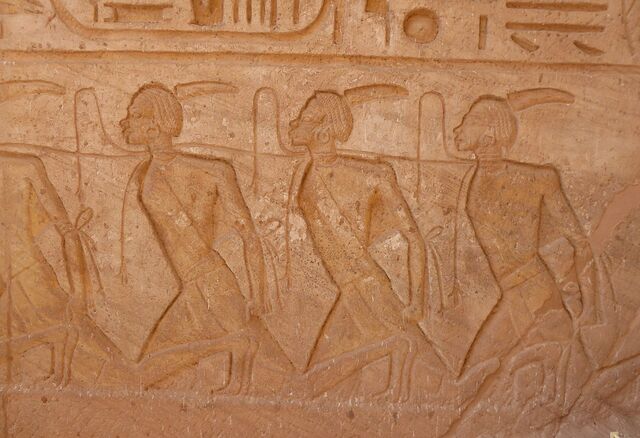

Archaeologists excavating the 3,550-year-old tomb of Sobeknakht, governor of El Kab (near Thebes), came across a dramatic 22-line hieroglyph wall inscription, showing that the “kingdom of Kush came close to destroying its northern neighbor.” Vivian Davies, keeper of the British Museum’s Department of Ancient Egypt and Sudan, summarized the finding as “the discovery of a lifetime, one that changes the textbooks. We’re absolutely staggered by it.” As reported by the Times, the fact that such a significant defeat at that time was unknown by researchers shows that the ancient Egyptians must have “‘airbrushed’ out of history one of their most humiliating defeats in battle.”

Davies described the inscription content: “It was a huge invasion, one that stirred up the entire region, a momentous event that is previously undocumented. They swept over the mountains, over the Nile, without limit. This is the first time we’ve got evidence. Far from Egypt being the supreme power of the Nile Valley, clearly Kush was at that time. Had they stayed to occupy Egypt, the Kushites might have eliminated it. That’s how close Egypt came to extinction” (emphasis added). The inscription also described the buried Sobeknakht’s attempt to launch a counterattack.

What did Josephus say of this time period? “The Ethiopians, who are next neighbors to the Egyptians, made an inroad into their country … and thinking that it would be a mark of cowardice if they did not subdue all Egypt, they went on to subdue the rest with greater vehemence; … they proceeded as far as Memphis, and the sea itself, while not one of the cities was able to oppose them” (Antiquities, 2.10.2). Egypt faced total destruction! Josephus’s account was proved dramatically accurate.

Josephus further described the pillage of Egypt. Archaeologists had already found evidence of this in rich Egyptian goods buried in Kushite tombs—but these opulent finds were thought to have been the result of trade. It was only with the tomb discovery in 2003 that two and two were put together—evidence that these Egyptian goods in the hands of Kushites constituted the spoils of war.

Total Victory for Egypt

According to Josephus, it was some time following this humiliating defeat that God inspired the Egyptians to choose the young prince Moses to lead the fight back—and that this led to a complete reversal of fortunes, with the stunning defeat of the Kushites. (Additionally, Egypt’s geographic dominance was necessary to fulfill the prophecy God made to Abraham of the Israelite oppression and Exodus, as in Genesis 15.)

According to biblical chronology (as we recently explained here), Moses was born in the mid-late 1500s b.c.e., leading Israel out of Egypt in the following century. (As an aside, Mose/Mosis was a common royal Egyptian name-element at this time—recall the Egyptian princess named the Hebrew child Moses.) This means that it was sometime around the end of the 1500s that we could expect to find Moses in his prime as a prince of Egypt.

And what do we find? Archaeology and secular history show that it was right at this time that Egypt turned and conquered the Kushites—ending the Kushite/Kerma kingdom for the next 500 years, and turning it into an Egyptian province!

It was during the reign of Tuthmose i that Lower Nubia (northern Kush) was initially pushed back (around 1520 b.c.e.), and after a “long campaign,” the Egyptians finally conquered Upper Nubia (southern Kush). Note that Josephus and Artapanus especially describe this later fight in the context of Moses, deep into southern Kush—a campaign that was “10 years” long.

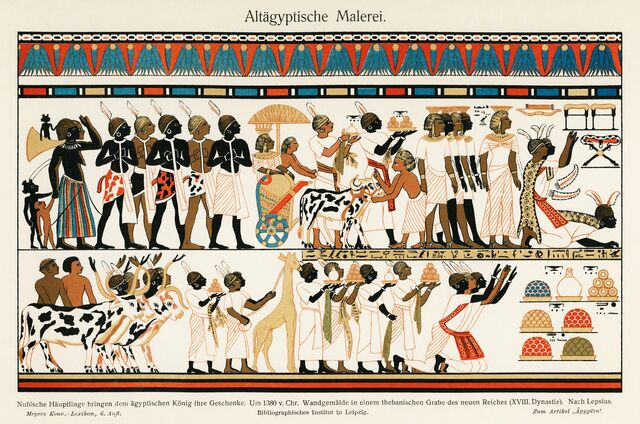

But conquered they eventually were, and it is from this period—around 1500 b.c.e.—to roughly 1000 b.c.e. that Egypt turned Kush into a province of Egypt. A new leadership position, “viceroy of Kush,” was established to rule the territory under the pharaoh. (The below image shows the conquered Kushites bringing gifts to the pharaoh of Egypt, circa 1400 b.c.e.)

A Strange Affection

A final question: Why would the Ethiopians—to quote Artapanus—“become so fond of Moses” if he was their conqueror? Why would Princess Tharbis show such favor? A possible answer to this can also be found in the classical histories and in archaeology.

Josephus related that, though God inspired the Egyptian choice of Moses to lead the campaign against Kush, the Egyptians did not think he would survive and actually reveled in the thought that this war would put an end to the prince (similar to the logic of King Saul’s sending David to battle against the Philistines; 1 Samuel 18). “So Moses … undertook the business: and the sacred scribes … were glad; those of the Egyptians, that they should at once overcome their enemies by his valor, and that by the same piece of management Moses would be slain …” (op cit). Moses’s challenge to overcome Ethiopia was no personal vendetta—it was supposed to kill him. If this reason became known to the Ethiopians, perhaps it led to some sympathy. Added to that, there is also that ancient deference to and respect for power: the strength of an opponent and his skill in battle. Additionally, Artapanus indicates such favor related to Moses’s governorship and construction projects.

But there is also another key archaeological link to the favor shown toward Moses: The kingdom of Kush had long prior enjoyed good relations with the Semitic population in northern Egypt—the territory of Goshen.

This brings to mind the famous story of Joseph and his family in Egypt—Joseph being raised in rank to second-in-command under pharaoh, and his family immigrating to and being given the land of Goshen. This led to a situation, as shown by archaeology, in which foreign Semites gained total control of Lower (northern) Egypt during the first half of the second millennium b.c.e.; the native Egyptians in turn dominated the south (Upper Egypt), on the border of Kush. These foreign, non-Egyptian, Semitic northern leaders were named the Hyksos. Josephus directly identified the Hyksos as being Israelites, translating this Egyptian title to mean “shepherd kings.”

Archaeological evidence shows significant trade of precious materials between Kush and the Hyksos Semites—namely, gold and ivory coming out of Kush and a flush of earthenware coming into Kush from northern Egypt. (Interestingly, this pottery is called Tell el-Yahudiyeh—“Jewish Mound”—Ware, also “Canaanite” Ware, given its prevalence throughout the Holy Land.) So significant was the economic relationship, that an inscription records Kamose, native Egyptian pharaoh of the southern Upper Egypt (early-mid 16th century b.c.e.), accusing the kingdom of Kush and the Hyksos rulers of attempting to “squeeze out” Egyptian rule. (It’s worth noting that his Egyptian advisers protested that this was not the case.) Eventually, a building resentment culminated in the Egyptian overthrow of Hyksos rule and the oppression of the northern, Semitic-dominant Egypt. It appears that following this event, the kingdom of Kush made its successful invasion north, against the native Egyptians—followed by the ultimately successful native Egyptian counterattack to the south, at the end of that century.

This “pre-Moses” economic alliance and friendship between Kush and the Semites of northern Egypt might explain the favor and respect toward Moses, despite his upbringing in the courts of native Egypt—and ultimately, could explain even the friendship and resumption of trade between the Queen of Sheba and Solomon. (And is it coincidence that this Solomonic episode began soon after Kush finally became autonomous from Egypt, at the end of the second millennium b.c.e.?) It may even help explain why the Ethiopian Amharic script, whose ancestral alphabet emerged around this time period, has close connections to the early Hebrew alphabet.

Of course, the personalities in this conquest story themselves are harder to pin down—notably, Tharbis of Kush and Moses the Hebrew. Actually, very little is known about the individual Kushite rulers, much less their princesses. And as we have covered, given that even the near extinction of the kingdom of Egypt in the 16th century b.c.e. was not realized until 2003—“airbrushed” from history as an embarrassing defeat—it would not be surprising for the same to have been done regarding Moses and the Exodus. (Still, there is broader evidence for that.)

A Special Relationship

Throughout the course of history, Kush/Ethiopia has had a unique connection with Israel. It is indicated in the evidence of trade relations between Kush and the Semitic leaders of northern Egypt. It is retold in the above accounts of Moses. It crops up again with the Queen of Sheba’s visit to King Solomon, “with a very great train, with camels that bore spices and gold very much, and precious stones; and when she was come to Solomon, she spoke with him of all that was in her heart” (1 Kings 10:2). It is seen in the Kushite-native Pharaoh Tirhakah’s alliance (albeit misguided) with Hezekiah, against the might of the Assyrian Empire (2 Kings 19; Isaiah 37).

It can be seen in the example of “Ebed-melech the Ethiopian, an officer, who was in the king’s house,” serving King Zedekiah. While the Jewish leaders at the time attempted to kill the Prophet Jeremiah, Ebed-melech led a 30-man team to rescue him, and was blessed by God for his actions (Jeremiah 38-39).

It is also possible that certain of the likewise Egyptian-oppressed Kushites were among the Israelites in the exodus from Egypt. After all, Exodus 12:38 says that a “mixed multitude” went out together with the Israelites. The biblical requirement was for foreigners to be circumcised to enter into the congregation of Israel (verse 48)—something that, because of Moses (according to Artapanus), many of the Ethiopians were.

And we later see indications of what could be other Kushite individuals among the children of Israel—individuals specifically named Cushi (a name literally meaning Kushite). There was Cushi, King David’s personal messenger-runner (2 Samuel 18; fitting, given that Africa produces the fastest runners in the world!). There is the officer Jehudi, descendant of another “Cushi,” who encouraged the persecuted Jeremiah’s scribe Baruch to read the scroll of God before the princes of Judah (Jeremiah 36:14). Even the Prophet Zephaniah himself, who served at the time of King Josiah, was a “son of Cushi” (Zephaniah 1:1), which has led to speculation that he was perhaps in part of African descent.

On a personal level for our own organization, that relationship continued with our predecessor Herbert W. Armstrong and the favor extended to him by the late emperor of Ethiopia, Haile Selassie of the Solomonic Dynasty (a leader styled with the title “Lion of the Tribe of Judah”).

And that unique connection with Israel continues to this day, notably demonstrated by the significant Ethiopian Jewish community, with a large population living within Israel. Much of this population is directly associated in name with Moses, by way of the Mossad’s “Operation Moses”—the dramatic rescuing of Ethiopian Jews by Israeli agents and their Ethiopian contacts in the 1980s. This fascinating modern “Exodus” story has recently garnered worldwide attention through the Netflix feature film The Red Sea Diving Resort.

In some respects, then, you could say that Tharbis’s reaction to the prince lives on among her people today—in the respect and admiration continued to be had for a prophet, shepherd, leader and military general: Moses.