There’s nothing like finding a beautifully preserved artifact with a clear, unbroken inscription. Trouble is, that never really happens. More often than not, the “money” part is broken off or missing—the most important part so often seems to be the section that is broken. And that is certainly the case with biblically significant artifacts. An inscription will describe a biblical character to a T, to the point where the identification is virtually certain—yet the name will be broken off.

That’s not to say it happens all the time, or that very few biblical figures have been proved through archaeology. Currently the tally stands at 53, according to Prof. Lawrence Mykytiuk’s stringent analyses (this is the number just for individuals mentioned in the Hebrew Bible, or Old Testament). Mykytiuk’s list has an additional 13 “nearlies.”

It is the archaeological “nearlies” that I want to focus on in this article. They aren’t given as much publicity, of course, due to their fragmentary nature. But they do provide a great deal of biblical evidence in themselves. And they actually highlight some dangerous trends.

Isaiah

The Isaiah bulla is a case in point. Actually, this artifact can be seen as more than a “nearly.” There is a general consideration that this artifact did actually belong to the biblical prophet. But because of a broken letter, debate has raged among members of the scholarly community, and thus some degree of doubt still hangs over this artifact. And so here, it illustrates the semantic difficulties nicely.

All the evidence is there. The bulla (seal stamp) was found in a controlled scientific excavation. It dates to exactly the same period as the biblical prophet. It belonged to a high-ranking official, as was the prophet. It was found in a royal quarter of Jerusalem, where the biblical prophet lived and worked. It was found right alongside a bulla belonging to King Hezekiah himself, whom the prophet worked with closely, as evidenced in the Bible; the king and prophet are mentioned together in 16 different verses. The title on the bulla clearly reads Belonging to Isaiah. It was merely the final word—actually, just one letter of the final word—that has generated so much scholarly debate as to whether or not we can be absolutely sure it belonged to the prophet. The final preserved word is Nvy. The Hebrew word for “prophet” is Nvy’ (both pronounced the same). The place where the final symbol was expected had been damaged by a 2,700-year-old fingerprint.

Hence the debate—over one little letter. Without this letter (aleph), some of the more skeptical scholars argue, the word Nvy could just be a family name or a location.

But as Dr. Eilat Mazar (the archaeologist who uncovered it) keeps coming back to, what are the chances that this is just another “Isaiah”? Given all of the above, the wider context, that fits so perfectly—given that the word “prophet” is all there, minus one letter?

All the evidence points to this being the Prophet Isaiah. Still, due to the tiniest bit of damage over one single letter, the curse of doubt has been introduced. And to the scholarly world, the tiniest speck of doubt makes even the unreasonable reasonable. Cue the flurry of articles, as certain skeptics jump on the “not so fast” bandwagon—typically ignoring the context and instead focusing on semantics regarding the missing letter.

Yet regarding that final letter, a close reexamination of the bulla appears to show a partially preserved aleph after all—thus completing the word prophet.

Elisha

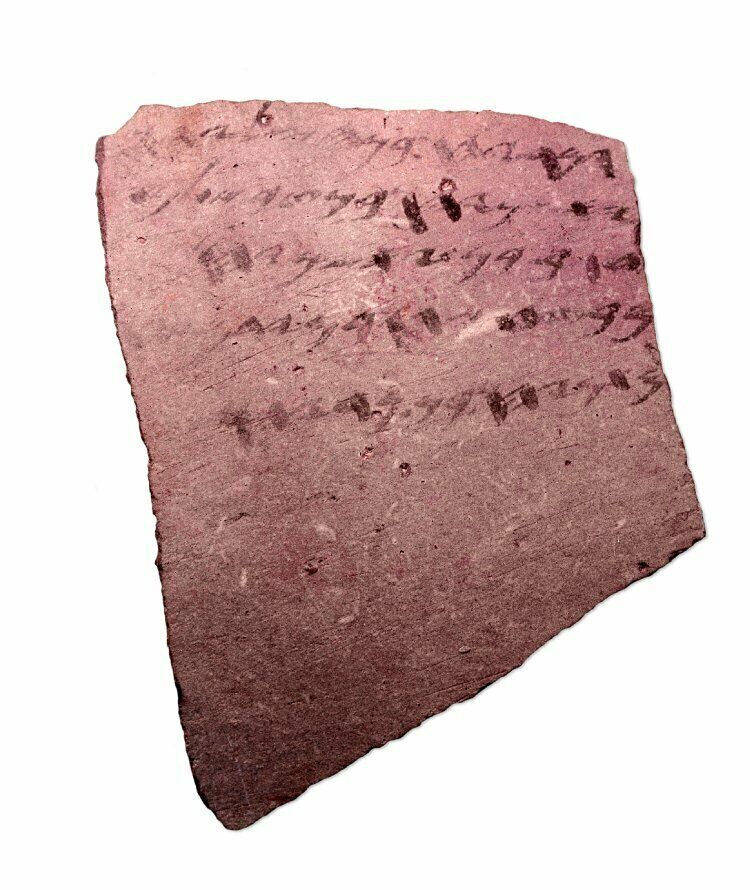

This inked potsherd inscription (ostracon) was discovered at Tel Rehov, dating to the middle of the ninth century b.c.e. It was broken into two sherds, with a chunk missing—apparently out of one single letter. However, it can still be translated with virtually complete certainty as the name “Elisha,” as shown below:

The weight of evidence strongly supports this being the biblical prophet Elisha. Six elements about this discovery match up with the biblical prophet Elisha. You can read about them in our article “Elisha: The Prophet, the Legend, the History.”

Still, though, an element of doubt hangs over this fragmentary “nearly,” not least because of the broken nature of the inscription.

Jeremiah

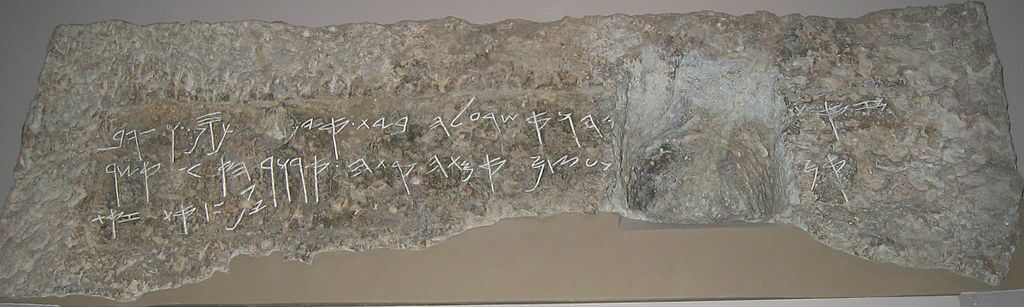

The Lachish Letters are a trove of ostraca dating to the time just before the destruction of Jerusalem, circa 586 b.c.e. They provide a unique snapshot of the time period just before the calamitous end of the southern kingdom of Judah.

One of the artifacts, Letter xvi, bears the following inscription:

your servant sent it … the letter of sons of [?] … [?]ah, the prophet.

There is some dissent about the translation of the word “prophet.” However, the above constitutes the widely accepted reading. In this case, only the last Hebrew letter of the prophet’s name survived, “-ah.” The most prolific prophet of this time period was Jeremiah, and it may well refer to him. However, there were at least two false prophets on the scene as well, both of which would fit due to their name-endings: Urijah and Hananiah. Just one more letter of the name, and we would have been able to identify which of these three individuals this was, or if it was perhaps a different man altogether.

Another longer letter describes an account reading very similar to the description of what happened to the prophet Urijah, in Jeremiah 26:20-23. Again though, while the link is likely, the letter is too fragmentary to be absolutely sure, and doesn’t mention the prophet by name—only his title.

Shebna

A rock-cut tomb lintel inscription was discovered just outside Jerusalem’s walls, dating to circa 700 b.c.e. The inscription is believed to almost certainly refer to the biblical steward and treasurer Shebna; however, most of his name had been purposefully gouged out of the inscription. It reads:

This is [the tomb of] … iah, which is over the house. There is no silver or gold here, only … [his bones] … and the bones of his maidservant with him. Cursed be the man who opens this.

The name at the start of the inscription is believed to be “Shebnaiah,” a longer form of the name “Shebna.” The phrase “which is over the house” is the ancient term for “royal steward”; this Hebrew title matches precisely with Shebna’s title in Isaiah 22:15. The cursed nature of his tomb provides a tantalizing link to Shebna’s tomb-curse of verse 16. We are just missing the name—as such, another biblical “nearly.” The name on the inscription was hacked out in an unusual, deeply curved fashion. Isaiah prophesied that the biblical Shebna would be tossed “like a ball into a large country.” Perhaps the name of this individual was quite literally carved out of the inscription into a ball shape, and tossed away.

David

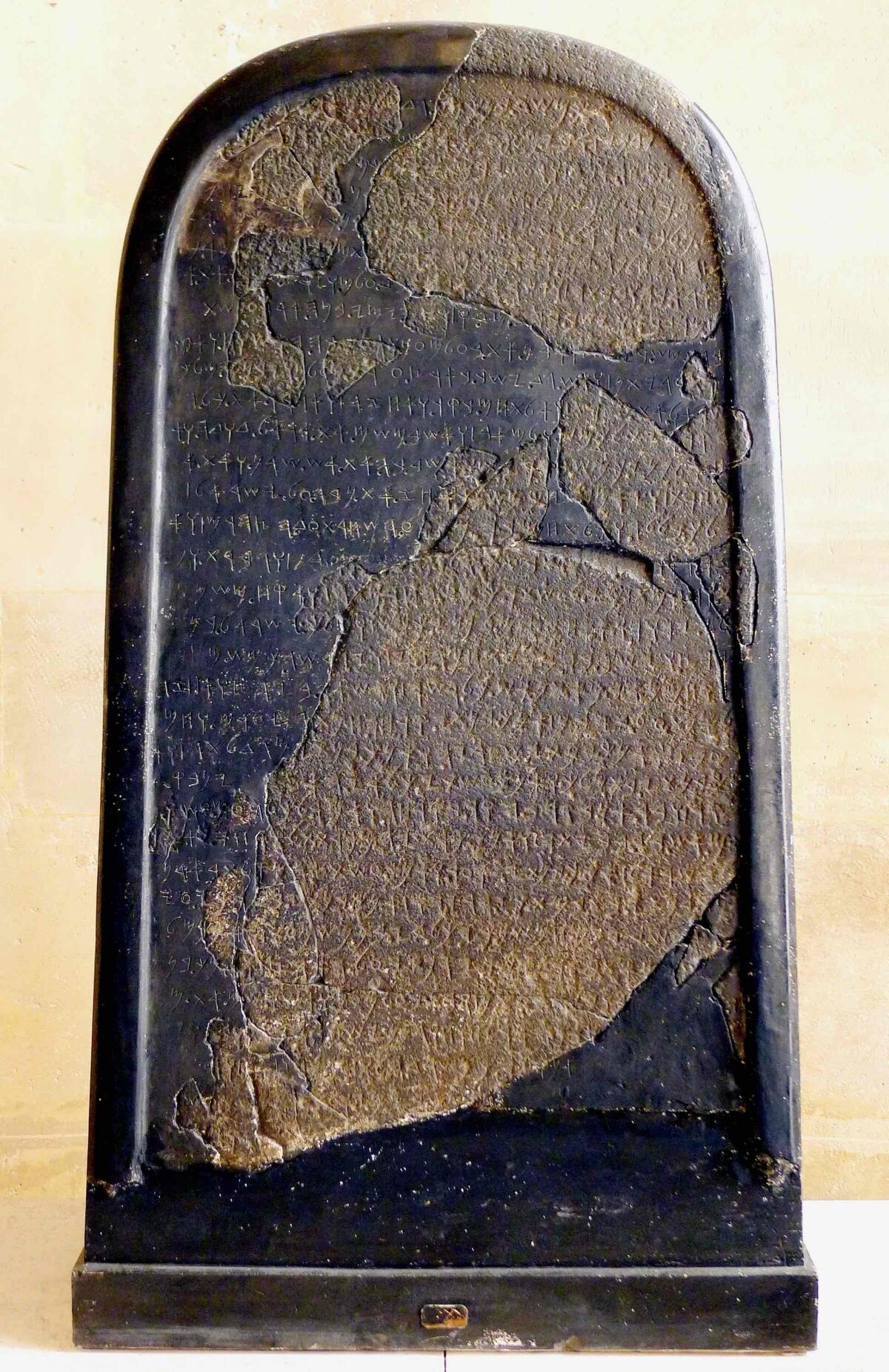

David has long been a divisive subject among scholarly circles. He was long believed to have been a simple figment of the imagination of the biblical authors. That is, until the Tel Dan Stele was found in 1993. Researchers tried every which way to translate the stele so that it would not say the phrase “House of David” (BTDWD)—but failed. Thus, the Tel Dan Stele became the first original, early artifact (circa 840 b.c.e.) discovered bearing the name of David, and establishing his kingly lineage.

Even though King David has been conclusively proved, another “nearly” reference has come to light, purportedly bearing the name of “David.”

This artifact is the Mesha Stele. This victory stone belonged to the Moabite King Mesha, and celebrated Moab’s rebellion against the king of Israel around the middle of the ninth century b.c.e. (2 Kings 3). Toward the base of the inscription, the same phrase used on the Tel Dan Stele can be found: “house of David.” However, due to damage, the initial “D” is missing (i.e., BT[D]WD). As such, this artifact is given a “nearly” stamp. But according to epigrapher and philologist André Lemaire, who carefully studied the artifact, any reading other than “David” would be an awkward fit. So while the inscription isn’t 100 percent sure, it certainly makes for convincing accumulative evidence.

Israel

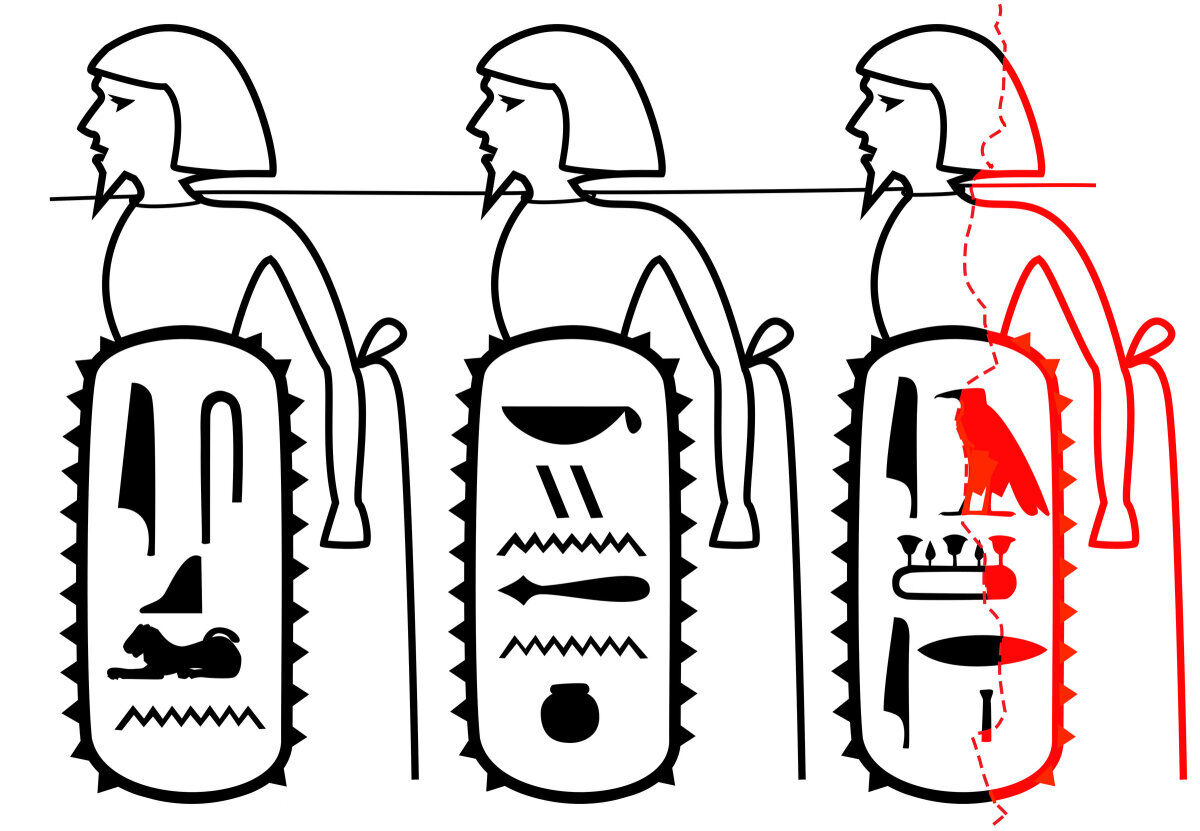

The Merneptah Stele is the earliest-confirmed reference to the name Israel, dating to circa 1207 b.c.e. Yet there is a likely far earlier reference to the name of the nation. This artifact is known as the Berlin Pedestal, and it dates perhaps as early as the 15th century b.c.e. There’s one problem: The name “Israel” is broken.

Actually, there are a couple of problems. Primarily, the Egyptian carving is broken off along its right side, throwing into doubt one key hieroglyphic component—a vulture, in order to complete the name “Israel.” Still, a portion of this hieroglyph does remain (a beak and apparent leg, see below), making it as good as certain that this broken hieroglyph really was a vulture.

The second issue is the transliteration of the complete name, using the vulture hieroglyph. Certain Egyptian hieroglyphs can be interchangeable for different sounds. Still, according to researchers Dr. Peter van der Veen and Dr. Christoffer Theis, the best transliteration of the inscription is I-3-ŠR-I-L, or Israel.

Such “nearlies” are unbelievably frustrating! Artifacts that come so close—essentially, virtually, 99.9 percent certain—yet still have a shadow of doubt hanging over them.

Critics really capitalize on the minutest smidgen of uncertainty. Scholars thrive on introducing doubt into the equation—seeking to make even the most improbable answers seem probable. And many a scholar has built a career around attempting to disprove the biblical account, taking the position that unless it is 100 percent proved, it must not have happened, or he must not have existed. But a lack of absolute corroboration doesn’t mean it never happened—that he or she never existed. And the “nearlies” do provide a weight of accumulative evidence that cannot simply be ignored.

Erasing History

We’ve covered only some examples of “nearlies” that have been damaged. There are many more names that are undamaged, but simply don’t have quite enough information to securely link to a biblical personality. In such cases though, even raw, generic names provide support for the biblical account. (Read our article “Biblical Names Confirmed Through Archaeology” to learn more.)

Regarding the broken names though: Oftentimes, the damage is all a bit too “convenient.” Such is the case with the Berlin Pedestal and the Lachish Letters. “Convenient” damage, but subtle—as opposed to more overt damage, such as with the Shebna Inscription.

The Mesha Stele is an example of overt damage, yet not with the specific intent of erasing the reference to “David.” The stele was discovered in the 19th century, in the possession of Bedouins. Archaeologist Charles Clermont-Ganneau procured a generally complete schematic copy of the artifact. After realizing the full importance of the artifact, however, the Bedouins broke it up and distributed it among their tribes. Some of the pieces later showed up on the Antiquities Market, and after being purchased, the Mesha Stele was able to be partially reconstructed (hence the fragmentary appearance). Most of the missing portions of text were able to be filled in based on Clermont-Ganneau’s copy. Still, some of the original text—such as the full name of King David—has unfortunately been lost.

But that’s the story of man’s history—a chronicle of lost information, misinformation, disinformation. That was certainly the case in the ancient world. Inscriptions were smashed, statues defaced. Conquered kings and loathed individuals had their names and faces chiseled out of monuments. This display of revulsion may not have had an immediate effect of erasing the memory of the individual in question, but in the centuries and now millennia that have followed, historians and archaeologists still struggle with the aftereffects.

Of course, this type of destruction and suppression of historical record has followed us all the way up through the Dark Ages and even into our “enlightened” Information Age. A relatively recent example being the Nazi book burnings: In 1933, numerous large rallies were held around Germany, where tens of thousands of Jewish, Communist, pacifist, liberal and generally “un-German” books were burned to ashes. And who could forget the 2015 video footage of Islamic State militants sledgehammering artifacts and detonating parts of the ancient Assyrian city of Nimrud?

Certainly, evil powers do have a vested interest in the destruction and rewriting of history. And—at least, to the believer—the same could be suggested for the conveniently damaged biblical artifacts: a satanic power with a vested interest in destroying biblical evidence, at least just enough so that doubt remains. There are many examples of these very nearly artifacts.

It is easy to think that, in the quest for knowledge, evidence and proof, mankind has gradually progressed from a degenerate, backward, ignorant state to an enlightened and informed one. Actually, that is not the case. Man’s history of knowledge has had peaks and valleys. And it has only really been over the past couple of hundred years that scientists have rediscovered some incredibly detailed medical and scientific knowledge found in the pages of the Bible. You can read more about that in our article “The Bible Scoops the Scientists.”

Alongside these general scientific rediscoveries, archaeologists have also been rediscovering proof of dozens of biblical individuals over the past couple of hundred years. Individuals that were thought to have been mythical. This wasn’t necessarily a case of information being lost, but rather of historical information not being believed.

And so today, we now have multiple dozens of biblical individuals re-proved. Added to that, we have a whole host of “nearlies.” Individuals, again, still not yet believed—although the weight of evidence makes them virtually certain. And—at least in a court of law—that weight of evidence dictates the verdict.