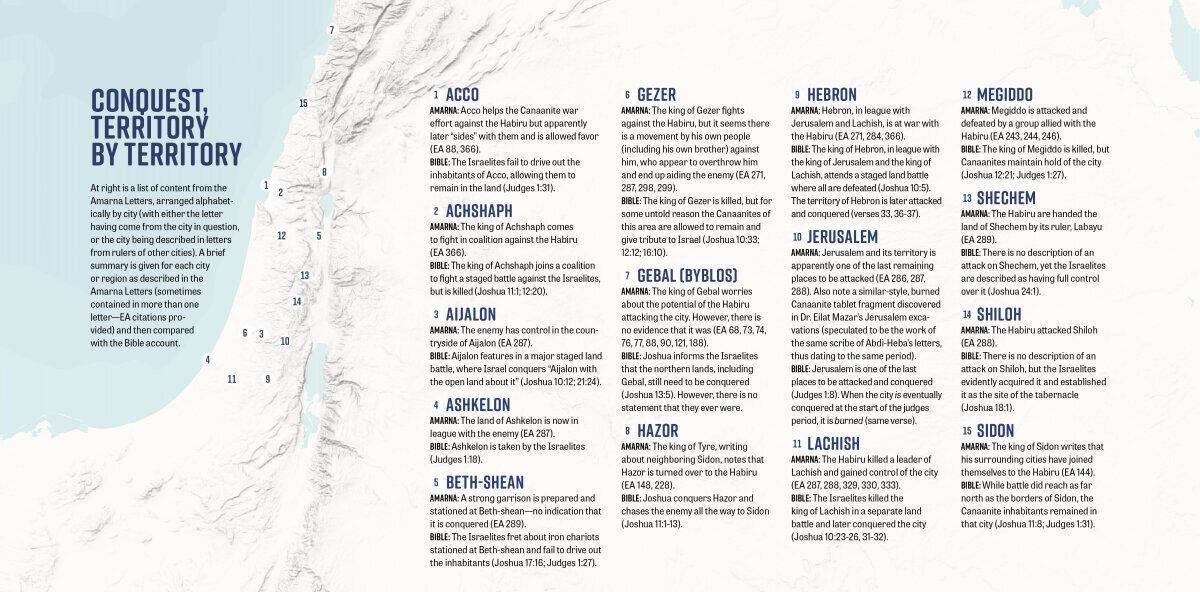

In previous articles discussing the 14th-century b.c.e. Amarna Letters, we have made the case that they do indeed preserve record of the Israelite conquest of Canaan—that the mysterious Habiru conquering “all the lands” are none other than the biblical Hebrews on the scene right around the time indicated by Bible chronology. We have highlighted a city-by-city comparison of the Amarna and biblical conquest texts, demonstrating corresponding parallels, as well as a potential reference in the Amarna archive to Joshua himself.

There is yet another interesting angle to this topic, demonstrating a level of verisimilitude between the Bible’s conquest account and the Amarna Letters: titles and formal address.

‘My Lord, Your Servant’

Joshua 5 details Israel’s advance toward Jericho to siege this first of the cities of Canaan: “And it came to pass, when Joshua was by Jericho, that he lifted up his eyes and looked, and, behold, there stood a man over against him with his sword drawn in his hand; and Joshua went unto him, and said unto him: ‘Art thou for us, or for our adversaries?’ And he said: ‘Nay, but I am captain of the host of the Lord; I am now come.’ And Joshua fell on his face to the earth, and bowed down, and said unto him: ‘What saith my lord unto his servant?’” (verses 13-14).

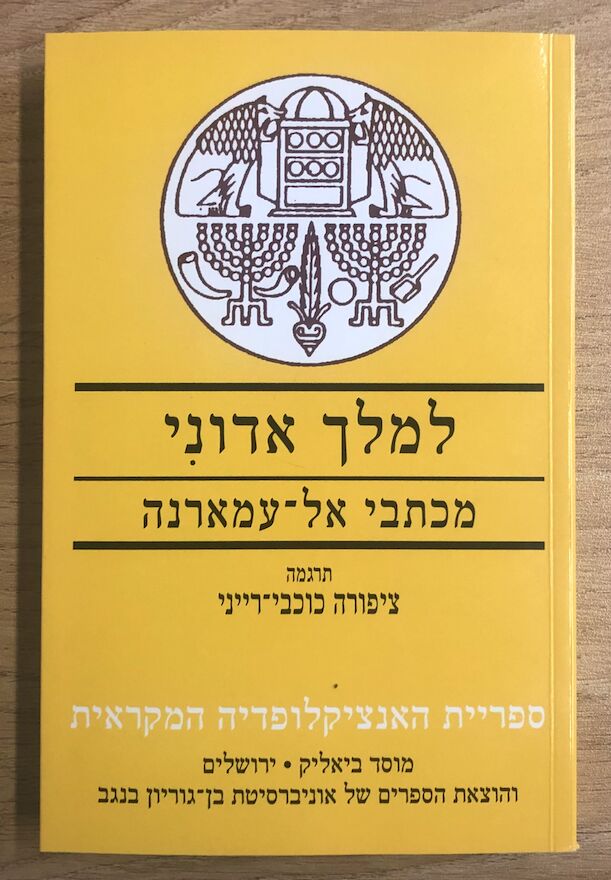

Those familiar with the Amarna Letters will immediately recognize this refrain of “my lord [Hebrew: adoni] … his servant”—a turn of phrase ubiquitous throughout the correspondence. The authoritative translation of this corpus into Hebrew is found in Prof. Zipora Cochavi-Rainey’s rather appropriately titled book, ‘To the King, My Lord’ [Adoni]: Letters From El-Amarna, Kumidu, Taanach and Other Letters of the 14th Century B.C.E. Some examples of this language comes the following letters (abbreviated EA, “el-Amarna”):

- EA 53: “my lord: Message of Akizzi, your servant”; “I am a servant of the king, my lord”

- EA 55: “my lord, I am your servant”

- EA 56: “your servant and my lord”

- EA 59: “My lord, thus says Tunip, your servant”

- EA 79: “my lord heed the words of his servant”

- EA 88: “my lord has done nothing for his servant”

- EA 94: “Why has my lord not heeded the words of his servant?”

- EA 103: “my lord, heed the words of his loyal servant” (three times)

- EA 121: “my lord loves his servant”

- EA 118: “my lord: Message of Rib-Hadda, your servant”

- EA 144: “my lord, when he wrote to his servant”

- EA 147: “my lord, to his servant”; “the servant said to his lord”; “the servant who gives heed to his lord”

- EA 148: “my lord give his attention to his servant”

- EA 189: “my lord: Message of Etakkama, your servant”; “my lord, I am your servant”

- EA 228: “loyal servant of the king, my lord”

- EA 252: “my lord, say: Thus Labayu, thy servant. At the feet of my lord I fall”

- EA 271: “my lord, ask Yanhamu, his servant”

- EA 286: “my lord: Message of Abdi-Heba, your servant”

- EA 288: “my lord, I am your servant.”

These represent only a fraction of the examples of this language found in the corpus of Amarna Letters. The words of Joshua to the mysterious figure near Jericho—“What saith my lord unto his servant?” (Joshua 5:14)—are virtually an exact parallel.

But there’s more to it than that. The biblical passage also says that just before using this refrain, “Joshua fell on his face to the earth, and bowed down ….” This is also mirrored in the Amarna Letters: In addressing the pharaoh, immediately following the “my lord, his servant” language, are the words “I fall at the feet of my lord” (or a variation thereof).

And then there are the peculiar names of conquest-period rulers.

Adoni- Names

“Although the place names of the Amarna texts are parallel to those of the Old Testament, the personal names are totally different,” wrote Dr. Charles Pfeiffer in Tell El Amarna and the Bible (1963). Not so much—as we have covered previously—with relation to the Exodus-period names like Joshua, Judah, Malkiel and Heber (as well as other parallel names not specific to this time period, such as Job).

There is another interesting connection in relation to the “my lord,” or Adoni, terminology. It is exclusively during this conquest period that we find hyphenated “Adoni-” names in the Bible.

In Joshua 10, we are introduced to Adoni-Zedek (אדני-צדק), ruler of Jerusalem (verses 1-3). In Judges 1, shortly after the death of Joshua, we are introduced to Adoni-Bezek (אדני-בזק), ruler of Bezek (verses 5-7).

Much has been written on the nature of these names and rulers—particularly the ruler of Jerusalem. Some proponents of the Amarna-Israelite conquest connection have wondered if Adoni-Zedek might have been an earlier or later ruler of Jerusalem, given that the ruler of Jerusalem in the Amarna archive is named Abdi-Heba—from whom we have some of the most vivid language in the Amarna Letters concerning the Habiru invasion: “All the lands of the king [pharaoh], my lord, have deserted”; “Lost are all the mayors”; “The Habiru has plundered all the lands”; “the land of the king is lost”; “I am situated like a ship in the midst of the sea”; “the Habiru have taken the very cities of the king”; “all is lost.”

But what of Adoni-Zedek—and, by extension, Adoni-Bezek?

Rather than personal names, it is apparent that these are titles, with the similar adoni- element—although instead of meaning “my lord,” when juxtaposed against a proper noun, meaning “Lord of [xyz].” Thus, “Lord of Zedek” and “Lord of Bezek.” This is seen most obviously with “Adoni-Bezek,” king of Bezek—the name “Lord of Bezek” clearly representing his title, as ruler of this territory. But what about Adoni-Zedek, king of Jerusalem?

The reader will already undoubtedly be familiar with a number of different names for Jerusalem: Salem, Jebus, Zion, City of David. Zedek (meaning “righteous,” or “righteousness”) is in fact another. This can be seen reflected in the name of the first mysterious “King of Salem,” Melchi-Zedek—a name that can be translated both as “King of Righteousness” and “King of Zedek.”

Other passages intimate this very thing. Isaiah 1:26 says of Jerusalem: “I will restore thy judges as at the first, And thy counsellors as at the beginning; Afterward thou shalt be called The city of righteousness [Zedek], The faithful city.” In the words of Jeremiah: “The Lord bless thee, O habitation of righteousness [Zedek], O mountain of holiness” (Jeremiah 31:23); “Jerusalem shall dwell safely: and this is the name wherewith she shall be called, The Lord our righteousness” (Jeremiah 33:16; King James Version); “[T]hey have sinned against the Lord, the habitation of justice [Zedek]” (Jeremiah 50:7). Other passages bring out the same sense (e.g. Ecclesiastes 3:16). The Midrash Rabbah (xliii. 6) states, “The King of Zedek, The Lord of Zedek (Joshua 10:1). Jerusalem is called Zedek (righteousness), as it is written, Zedek (righteousness) lodged in her (Isaiah 1:21).”

Thus, as with Adoni-Bezek, ruler of Bezek, Adoni-Zedek aptly represents a title for the ruler of Jerusalem and could very well have been borne by the likes of Abdi-Heba, or any other ruler of Jerusalem bearing a different personal name. Easton’s Bible Dictionary goes so far as to directly equivocate Abdi-Heba and Adoni-Zedek, writing that the “letters from Adoni-zedec to the King of Egypt … illustrate in a very remarkable manner the history recorded in Joshua 10.” And whether or not they are one and the same, as above, the “lord” appellation is also more than fitting for this period.

Abdi- Names

Just as with the lord (“Adoni-”) names, a similar case could be made for the servant (“Abdi-”) names.

A number of Amarna-period figures bear this name-element. We have already seen that of the ruler of Jerusalem—Abdi-Heba. Others include Abdi-Ashtarti, Abdi-Asirta, Abdi-Milki, Abdi-Risa and Abdi-Tirsi.

There are a handful of similar names within the biblical account relative to the general sojourn/Exodus/conquest setting, such as the “Abdi” mentioned in 1 Chronicles 6:29 (verse 44 in other versions) and 2 Chronicles 29:12, as well as “Abdi-el” mentioned in 1 Chronicles 5:15.

In Sum

“Despite numerous studies devoted to the question of who the ‘Habiru’ were, a lively controversy still continues,” wrote Dr. S. Douglas Waterhouse in his 2001 Journal of the Adventist Theological Society article, “Who are the Ḫabiru of the Amarna Letters?” “On the question of resemblance, it is now agreed upon that indeed there is a valid etymological relationship between the term ‘Habiru’ and the biblical name ‘Hebrew’ (‘ibri).” He goes on to elaborate further on parallels between the biblical account and the Amarna age, including other uses of titles among the Canaanites of the time:

While the title of a Canaanite chieftain was “man” (awilu: man with legal status) of such-and-such a city-state, and his appointed office, under an Egyptian overseer (a rabisu—official), was that of a “mayor” (hazannu), nevertheless, within his own Canaanite-society, he was known as “king” (EA 147:67; 148:40- 41; 197:13-14; 227:3; 256:8), exactly as he is called in the book of Joshua (Joshua 10:23). Similarly, the biblical phrase “kings of Canaan” (Judges 5:19; cf. Joshua 5:1) finds its duplication in the Akkadian expression “kings of Canaan” from the Amarna Letters (EA 30:1; 109:46; cf. 8:25).

Waterhouse highlighted other parallels, concluding that the Habiru of the Amarna Letters are the ideal fit with the biblical Hebrews and the account of their conquest, especially as pertaining to Jerusalem, Gezer and Shechem. He situates the Amarna archive more specifically within the period just following Joshua’s initial conquests—on the more-than-suspicious basis of “no word arriving at the Egyptian Court from such places as Jericho, Bethel, Gibeon, Shiloh, Mizpeh and Debir, those very cities captured by Joshua.”

Though there has been, and will continue to be, significant dispute on this subject (some of which Waterhouse discussed in his article), the level of parallels are striking—in my view, justifiably making the Amarna Letters (if I can use the title of Expedition Bible’s recent viral video) the number-one extrabiblical evidence for Israel’s conquest of the Promised Land—beyond any of the ongoing debates regarding individual city destructions, such as at Jericho.

For not only are the letters telling in both who, how and what is represented; they are also significant in who is not represented. “Within the Amarna archive from Egypt, it is telling that there are no letters from Jericho,” writes Bryan Windle in Joshua’s Jericho: The Latest Archaeological Evidence for the Conquest—this, despite evidence of administration at the site in the lead-up to this period, including a cuneiform tablet similar to the Amarna parallels, dated between the 15th to 14th centuries b.c.e. “If some of the Amarna letters are referencing events in Canaan during and after the period of the conquest, then perhaps Jericho, the first city conquered by the Israelites, had fallen before pleas for help could be sent to Egypt.” There is total silence from Jericho—no request for help from my lord to your servant.