Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Ekron

Few sites have a more diverse archaeological repertoire than Ekron. Located on the Judean frontier, this Philistine city was subject to many cultural influences that shaped its history and people. Ekron was one of the five major Philistine capital cities often referred to as the Pentapolis.

Ekron’s story is fascinating. In the Iron Age, it was the final of three Philistine cities that held the ark of the covenant. In the late eighth century b.c.e., Ekron was controlled by Judean King Hezekiah, and then later dominated the trade of olive oil under the Assyrian Empire. Ekron’s significant archaeological remains show that the Philistines were a well-known people for much longer than initially believed and that culturally they had a talent for adapting to the people around them.

Ekron, or what is Tel Miqne today, is about 35 kilometers (22 miles) southwest of Jerusalem, near Kibbutz Revadim, in the Judean lowlands. It was excavated over 14 seasons between 1981 and 1996 by archaeologists Prof. Seymour Gitin of the Albright Institute of Archaeological Research and the late Prof. Trude Dothan of Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Since 1996, the primary focus has been on publishing the many remarkable finds from this fascinating site.

Let’s dig in.

Early Ekron—Migration of the Philistines

The biblical text records that during Israel’s conquest of the Promised Land “Ekron, with its towns and its villages” was allotted to the tribe of Judah (Joshua 15:12, 45) but later transferred to Dan (Joshua 19:40, 43).

In addition to the many later Iron Age discoveries, excavations revealed evidence of occupation from the Chalcolithic to Late Bronze Age, which was earlier than the excavators expected. Some of the earliest strata contain Canaanite remains with imported Mycenaean and Cypriot pottery, revealing far-reaching international trade before the 12th century b.c.e. (the Late Bronze Age). No fortifications surrounded the city at this time.

Then a stark change occurs: In the next layer, the pottery shifts from the imported pottery of the Late Bronze Age to locally produced Mycenaean pottery of Iron Age i. Local production of the pottery is evidenced by a number of kilns found in the city’s southern industrial region.

This change marked the beginning of a foreign migration into the southern coastal region of the Levant at the start of the 12th century b.c.e. This change, and the destruction associated with the previous layer, reveal the main influx of the Philistines into the region. The transition takes place around the same time the Peleset Sea People (often associated with the Philistines) are first mentioned by Ramesses iii in the beginning of the 12th century b.c.e. Incidentally, a large portion of the animal bones found at Iron i Ekron were of pigs—common to all Philistine sites. Several pebbled hearths in the domestic area also reveal a Philistine presence, as this is a typical feature of Philistine culture.

The first layer of the clear Philistine occupation (Stratum vii) reveals that they inhabited all 50 acres of the tell, including the upper 10-acre acropolis at the northeast corner of the mound.

Analyzing the pottery finds from the site, Professor Dothan wrote that “the distinctly Mycenaean characteristics of this locally made pottery show the Sea People’s strong inclination to re-create in Canaan—at least in their pottery—the home environment of the Aegean world they came from.” The Aegean includes parts of Greece, Crete, Cyprus, Syria and Turkey. This parallels Amos 9:7, which says the Philistines came from “Caphtor,” which is identified with the island of Crete; dna analysis on Philistine skeletons has also confirmed this.

As the Philistines migrated, they did not lose their connection with their homeland. The Aegean origin of the inhabitants of Ekron is corroborated by many of the finds around Tel Miqne.

David’s Destruction?

Following the period of the judges, Ekron and the other Philistine cities were subdued by the Israelites in the battle that resulted in the death of Goliath (1 Samuel 7:14). Although Israel successfully defeated the Philistines, the archaeological record suggests Israel didn’t destroy or maintain a presence in the city. 1 Samuel 17 records that the Philistines came up against Israel during the reign of King Saul (late 11th century b.c.e.) but were defeated and driven back to Ekron and Shaaraim.

Like some of its neighboring cities, archaeological evidence shows that Ekron was completely destroyed between 1000 and 975 b.c.e., either by Pharaoh Siamun of Egypt or the Israelites under King David. Professor Gitin believes we can confidently identify Ekron’s destroyer: “No doubt the decline in the fortunes of Ekron was related to the ascendancy of David and his son Solomon and to the fact that Israel was now able to dominate the Philistines.”

After this destruction, Ekron became greatly diminished in size and power. It shrunk from a 50-acre city to a 10-acre acropolis at the northeastern corner. This event marked the end of the Iron i city. It remained a small, relatively inconsequential settlement for the next 270 years.

Because the monochrome and bichrome Philistine wares and hearths disappear in the post-1000 b.c.e. layers of strata iii-ii, scholars believed this was evidence that the Philistine occupation of the southern coast ended. Many believed, at this point, the Philistines became lost to history. Professor Gitin disagrees.

In “Excavating Ekron,” Gitin wrote, “As the archaeological evidence piled up … it became clear that the Philistines continued to exist, although they had adopted features of other cultures” (emphasis added throughout). This is just another example of a pattern that Professor Gitin identified. The Philistine inhabitants of Ekron had a talent for what he calls acculturation and continuation: They adopted the characteristics of their subjugators.

“Between about 1000 b.c.e. and the late seventh century b.c.e., the Philistines survived and sometimes thrived, absorbing cultural characteristics of their neighbors—the Israelites, the Phoenicians and, finally, the Assyrians,” he wrote.

After roughly 270 years of relative obscurity, the city of Ekron flourished again under the Assyrians.

Ekron, Assyria and Hezekiah

To understand Ekron in the seventh century b.c.e., it is important to consider it in the context of Assyria. Several societies or cultures collide in Ekron under the Assyrian Empire.

The Neo-Assyrian Empire started to invade the land of Israel in the latter half of the eighth century b.c.e. It conquered Samaria between 721 and 718 b.c.e. before setting its sights on Judah.

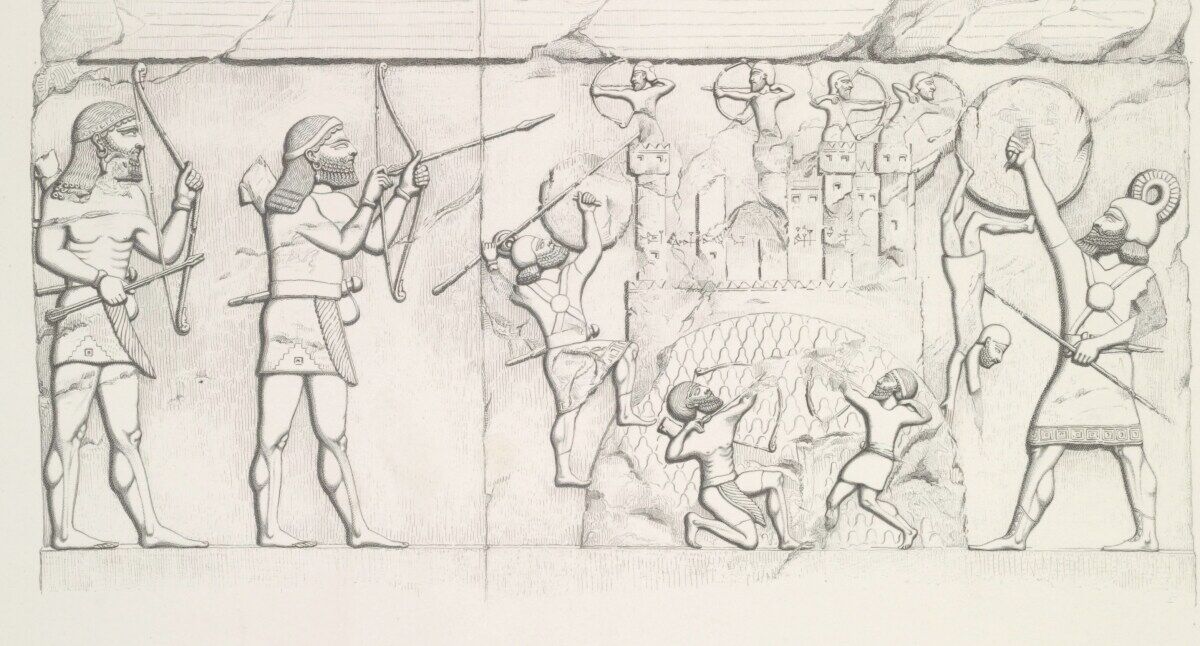

It appears Ekron was first sieged in 721 b.c.e. by Sargon ii, as shown on his wall reliefs at Khorsabad. A wall relief mentions Ekron by its Assyrian name, Amqarrûna, and specifically speaks of the Palaštu (Philistines) who lived there. The fact that the Assyrians mention the Philistines and their cities by name “indicates that the Philistines were still recognized as a distinct group with their own land and cities as late as the seventh century,” wrote Gitin.

Toward the end of the eighth century b.c.e., Ekron was sieged by another Assyrian king, Sennacherib. This too was documented. On his prism inscriptions, Sennacherib described the story of Padi, the Assyrian-installed ruler of Ekron who was put “into fetters of iron and given over to Hezekiah, the Jew” by the “officials, nobles and people of Ekron” when King Hezekiah conquered the city (2 Kings 18:8). Sennacherib then marched against Ekron on his campaign into Judah. “I drew near to Ekron and slew the governors and nobles who had rebelled,” Sennacherib recorded.

Archaeology attests to this recorded history. A small occupation layer dated to around 700 b.c.e. shows that the long-abandoned lower city was used for a short period before the Assyrian hegemony associated with the final stratum. This is interesting, as it lines up with Hezekiah’s occupation of Ekron described by the Assyrians.

More evidence of this was found in three storage jars in the upper acropolis that contained lmlk inscriptions, which means “belonging to the king.” Such inscriptions are typical of the late eighth-century reign of Hezekiah. (For more information, see “‘To the King’ Seals Point to Hezekiah”). The presence of these jars provide additional proof that Hezekiah did, in fact, have some measure of control over Ekron.

Olive Oil Production

Assyria’s rule of Ekron resulted in somewhat of a renaissance, marked by an increase in trade, size and prosperity. At the beginning of the seventh century, Ekron was rebuilt with new fortifications, including a massive three-way entry gate, and developed into a large, industrial, olive oil production center. According to Gitin, the city became “the largest olive-oil production center that we know of from antiquity.” More than 100 olive oil installations were found at Ekron, more than at any other site in Israel.

Olive oil production happened in lever-and-weight presses by a three-step process of crushing, pressing and separation. The buildings where these were found were divided into a press and a storage room. These installations were discovered alongside the southern wall in the domestic area, as well as in the temple complex at the center of the tell. This shows that oil was produced throughout the site.

The Bible describes olive trees being present in large numbers in the lowland area surrounding Ekron: “And over the olive-trees and the sycomore-trees that were in the Lowland [Shephelah] was Baal-hanan the Gederite; and over the cellars of oil was Joash” (1 Chronicles 27:28).

As the archaeologists note, the sheer amount of oil produced (probably over 230 tons annually) by the Philistines at Ekron suggests it was exported. This surplus was most likely traded through the Assyrian-controlled Phoenician markets—the Phoenicians themselves being supreme maritime traders.

According to Prof. David Eitam, however, Ekron’s oil factories would operate for only about six months in the year. What did the Ekronites do during the off season? This is where the other installations consisting of “vats and shallow basins” at Tel Miqne come into play.

Eitam pointed out that these could have been used for pressing wool and linen. Alongside the installations, they found a large amount of loom weights. Thus, “based on this data and in light of the large scale of the oil industry,” Eitam wrote, “we suggest that an extensive textile manufacture took place in the city in between the olive harvest seasons.”

Ekron it seems was a dual-use city, producing and exporting olive oil for half of the year and textiles the other half.

The Multicultural Temple

Immediately after the Assyrians conquered Ekron, making it a vassal city-state, the centerpiece of the site was constructed: Temple Complex 650.

The remains of this massive temple structure, which is 57 meters by 38 meters (187 feet by 124 feet), lie at the center of Ekron, in what is termed the “elite zone.” This is where Professor Gitin’s team made a special discovery: the majestic Royal Dedicatory Inscription.

According to Professor Gitin, the inscription is “the most important object” found at the site and “one of the most significant finds excavated in Israel in the 20th century.”

This large limestone block, weighing 150 kilograms (330 pounds), contains 5 lines of 72 letters. The inscription reads: “The temple which he built, ‘kys (Achish) son of Padi, son of Ysd, son of Ada, son of Ya’ir, ruler of Ekron, for Ptgyh his lady. May she bless him, and protect him and prolong his days, and bless his land.”

This inscription was a remarkable and unique find because it “allows us to declare with certainty that Tel Miqne is actually biblical Ekron,” Gitin said. Among other things, it forms “the basis for tracing the continuity of Philistine occupation at Ekron and the process of acculturation.”

For example, several of the names referenced on the stone tie the Philistines to their Aegean origins. The first name, Achish, has been taken to mean Aegean, or “the Greek,” and is also the name of one of the earlier kings of Gath, Ekron’s neighboring city (1 Samuel 21:11). This same king is also named in the prism of Esarhaddon, king of Assyria, as “Ikausu, king of Ekron.” The name is distinctly not of Semitic origin. Then there is the goddess to whom this temple and inscription were dedicated. Her name, Ptgyh, is connected to Pytho at Delphi—the shrine of the goddess Gaia of the Mycenaeans.

The language used at the temple as well as its construction reveal a strong connection to the Phoenicians, which, as suggested by Professor Gitin, most likely resulted from the strong commercial position of Ekron as an olive oil producer and exporter and the maritime prominence of the Phoenicians.

One of the side rooms of the temple structure contained another oil press installation along with 253 storage jars. One storage jar was inscribed with lb’l wlpdy, meaning “for Baal and for Padi.” This inscription confirms the worship of Baal at Ekron. The form of the inscription represents the common Assyrian usage of “for god and king,” displaying the Assyrian influence at Ekron.

Several four-horned altars were located around the site, including at the temple. This type of altar was common in the neighboring Judean religion.

In Building 350, the archaeologists found three bronze wheels, each having eight spokes, along with the corner of a stand. These discoveries were part of a wheeled stand “reminiscent of the biblical description of the mechonot, the laver stands made for Solomon’s temple in Jerusalem by Hiram king of Tyre,” wrote Professor Dothan. 1 Kings 7:30 describes Solomon’s lavers: “And every base had four brazen wheels, and axles of brass; and the four feet thereof had undersetters; beneath the laver were the undersetters molten, with wreaths at the side of each.”

Thus, especially in the seventh century, we find Ekron in the middle of a diverse and connected world, somewhat maintaining its historic connection to the Aegean while still adapting (perhaps out of necessity) to other cultures. We see Baal and Asherah worship at the temple, examples of tithing and Judean-type altars and offerings, references to the Aegean written in Phoenician style on the Royal Dedicatory Inscription, and a temple with Assyrian and Phoenician features—these are all proof of maximum acculturation.

Ekron Uprooted

Assyrian rule of Ekron came to an end around 630 b.c.e. and transitioned to a short period of Egyptian control, dividing Strata ib and ic. This brief Egyptian period saw a slight decrease in olive oil production based on some of the installations at the site falling out of use.

Ekron was issued its final destruction by Babylonian King Nebuchadnezzar in 604 b.c.e. In the Aramaic Saqqarah Papyrus, also known as the Adon Letters, Adon—possibly king of Ekron at the time—wrote to the Egyptian pharaoh for support against the Babylonian invasion—a request that history proves was left unanswered. According to Professor Gitin, this great destruction was proved by 3 feet of debris at the site covering the previous layer.

The name Ekron, which according to Strong’s Concordance means “emigration” or “torn up by the roots,” is a fitting description of the city that demonstrates the migration of the Philistine Sea People from the Aegean and their long-term settlement in the southern coast of the Levant.

About the end of this settlement, Zephaniah prophesied against the city, saying that “Ekron shall be rooted up” once more (Zephaniah 2:4). Only this time, the inhabitants of Ekron were permanently taken up by their roots and finally became lost to history—all “due to the long-term process of acculturation influenced by Ekron’s contacts with Assyria in particular, as well as the Israelites and Phoenicians, a process that left them without a sufficiently strong core culture to sustain them in captivity,” wrote Gitin.

Thus ended the story of the Philistine people at Ekron.

After the Philistines had gone into Babylonian captivity, the site was briefly settled at the start of the next century, but it quickly fell out of use until the Roman Period. Today, Kibbutz Revadim near Ekron has capitalized on its Philistine history. The story of this ancient people of Ekron is displayed in a reconstructed Philistine street and at the Ekron Museum of the History of Philistine Culture.

Articles in This Series:

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Ai

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Azekah

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Beersheba

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Beth Shean

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Beth Shemesh

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Dan

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Ekron

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Gath

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Gezer

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Hazor

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Hebron

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Jericho

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Jerusalem

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Khirbet Qeiyafa

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Lachish

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Megiddo

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Mizpah

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Samaria

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Shechem

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Shiloh

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Sodom

Videos in This Series:

Touring the Bible’s Buried Cities: Gezer