For all her contributions to the archaeological discourse on King David, our dear friend, the late Dr. Eilat Mazar, told me her favorite biblical king was Hezekiah. He was a more personable and relatable king, she felt—less of a warmonger and womanizer, whose actions did not result in such direct devastation (interfamily civil war, the census plague, etc). Conversations with her on such subjects while excavating on Jerusalem’s Ophel were always enjoyable.

But debate can certainly be had about the last point. For Hezekiah’s Judah was almost totally destroyed—and evidence suggests this was not some sudden, out-of-the-blue, entirely unexpected event.

The biblical account of the reign of King Hezekiah starts out almost like a fairy tale: “Now it came to pass in the third year of Hoshea son of Elah king of Israel, that Hezekiah the son of Ahaz king of Judah began to reign. … And he did that which was right in the eyes of the Lord, according to all that David his father had done. He removed the high places, and broke the pillars, and cut down the Asherah …. He trusted in the Lord, the God of Israel; so that after him was none like him among all the kings of Judah, nor among them that were before him. For he cleaved to the Lord, he departed not from following Him, but kept His commandments, which the Lord commanded Moses. And the Lord was with him: whithersoever he went forth he prospered …” (2 Kings 18:1, 3-7).

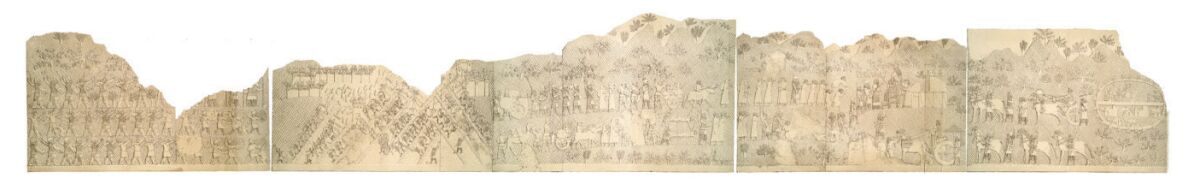

This makes it all the more jarring to read in the ensuing account, during the mid-to-latter part of Hezekiah’s reign, of a sudden and massive Assyrian invasion into the land of Judah in which “Sennacherib king of Assyria [came] up against all the fortified cities of Judah, and took them” (verse 13). Sennacherib’s own prism inscriptions note that “46 of his strong, walled cities” were destroyed, along with untold smaller towns. From these, besides those killed, “200,150 people, great and small, male and female” were taken captive. Reliefs from Sennacherib’s Nineveh palace portray in grisly detail the conquest and capture of Judah’s “second city,” Lachish, with captured individuals depicted being flayed alive and rammed through with wooden stakes to die the agonizing death of longitudinal impalement.

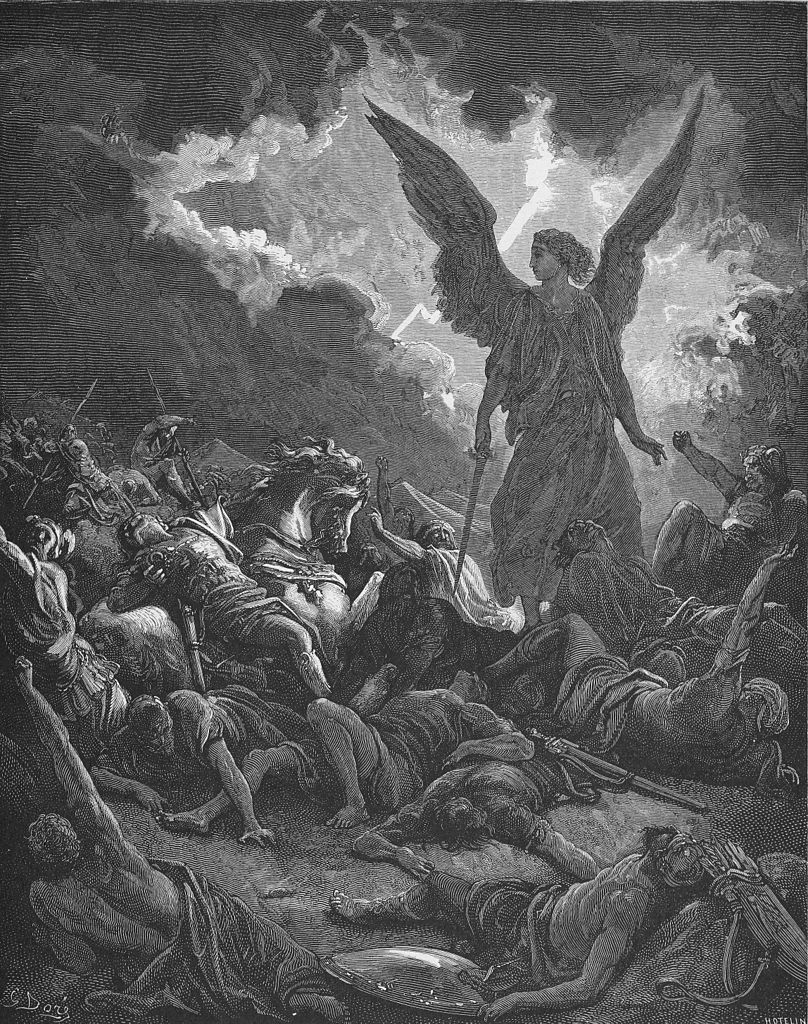

Those familiar with the biblical account well know that Hezekiah’s crying out to God for deliverance led to the capital city of Jerusalem being miraculously (and, from an archaeological/historical standpoint, inexplicably) spared.

But what happened to bring on this Assyrian onslaught?

Certain biblical clues and a growing body of archaeological evidence point to catastrophic decisions and events—at the core of which is the existential question: Whom to trust?

‘On Whom Dost Thou Trust?’

Following the initial account of praise for Hezekiah and his reforms, we read the following brief, yet geopolitically earthshaking, statement: “[A]nd he rebelled against the king of Assyria, and served him not” (2 Kings 18:7).

It is important to note the geopolitical situation at this time, near the end of the eighth century b.c.e. Assyria was at the height of its power. Barely more than a decade prior, it had destroyed and deported the northern kingdom of Israel and now wielded total control over the wider Mesopotamian and Levantine regions. Yet toward the end of the reign of Sargon ii and the start of that of his son Sennacherib, Hezekiah sought opportunity to break away and form a new geopolitical alliance.

Notable to this end, archaeologically, are the famous administrative lmlk-stamped pottery handles, widely attributed to the reign of Hezekiah. As summarized by epigrapher Dr. Daniel Vainstub: “Most researchers ascribe [the lmlk phenomenon] to King Hezekiah’s preparation for his rebellion against Assyria,” with certain of them labeled to signify “a huge and unique ad hoc collection of agricultural products initiated by King Hezekiah as part of his preparations for the anticipated invasion of the Assyrian army following his rebellion” (Jerusalem Journal of Archaeology, “The Enigmatic mmšt in the lmlk Stamps”).

Of course, one does not simply “rebel” without first making “friends.” And in attempting to reshape a new geopolitical alliance, whom did Hezekiah turn to?

Our first real clue comes from the harangue of Rabshakeh, Sennacherib’s officer, outside the walls of Jerusalem: “Thus saith the great king, the king of Assyria: What confidence is this wherein thou trustest? Sayest thou that a mere word of the lips is counsel and strength for the war? Now on whom dost thou trust, that thou hast rebelled against me? Now, behold, thou trustest upon the staff of this bruised reed, even upon Egypt; whereon if a man lean, it will go into his hand, and pierce it; so is Pharaoh king of Egypt unto all that trust on him” (2 Kings 18:19-21).

These are the very first quoted words from the Assyrian side. And right from the outset, what is their complaint—hedged about five times in just three verses with words of “trust” and “confidence”? It is that Hezekiah has rebelled against Assyrian hegemony and turned to Egypt as his partner.

Not that the enemy Rabshakeh’s word should be taken for it, though (an individual who is actually traditionally understood to be a Jewish traitor given his command of “the Jews’ language”—verse 26). Take it from someone else—the Prophet Isaiah.

A Dire Warning

The account of Hezekiah’s reign, Sennacherib’s campaign into Judah, and his miraculous defeat at Jerusalem, as found in 2 Kings 18-20, is paralleled in Isaiah 36-39. Several chapters earlier, however, we read of a dire warning from God through the prophet.

“Woe to the rebellious children, saith the Lord, That take counsel, but not of Me; And that form projects, but not of My spirit, That they may add sin to sin; That walk to go down into Egypt, And have not asked at My mouth; To take refuge in the stronghold of Pharaoh, And to take shelter in the shadow of Egypt! Therefore shall the stronghold of Pharaoh turn to your shame, And the shelter in the shadow of Egypt to your confusion” (Isaiah 30:1-3).

The passage goes on to condemn the reliance on Egypt, including such famous passages as the edict to the prophets to “[p]rophesy not unto us right things, Speak unto us smooth things, prophesy delusions” (verse 10)—sentiments that, as the passage continues to warn, would lead to disastrous consequences for the nation. This warning against a reliance on Egypt continues into the following chapter: “Woe to them that go down to Egypt for help …” (Isaiah 31:1). These warnings, delivered by the Prophet Isaiah, read suspiciously similar to the warnings that would reappear more than a century later from the Prophet Jeremiah—that Zedekiah and the kingdom of Judah not seek alliance with Egypt against the Babylonian Empire.

This ensuing episode of Sennacherib’s conquest of Judah is one of the most archaeologically attested to events in the Bible. Events, sieges, destruction layers (and a lack thereof at Jerusalem)—even certain personalities and tribute amounts have been substantiated by various discoveries, including inscriptions—and so too has the apparent Egyptian-orientation of Hezekiah’s administration.

Egyptian Administration

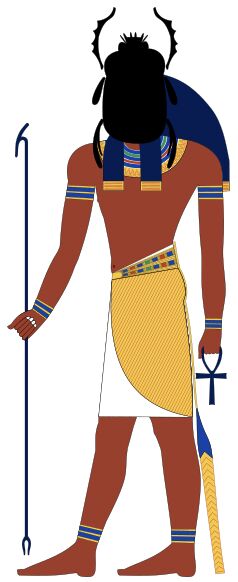

Most famous are the lmlk seals—many thousands of which have now been discovered, adorning the handles of pottery vessels that, as stated above, were probably designated to shore up supplies as part of Hezekiah’s rebellion. There are two main, prominent motif designs on these seals. One is a two-winged sun and the other—the most striking—is a four-winged scarab (depicted above). This iconography is clearly Egypt-derived and oriented, with the scarab serving to depict Khepri—the Egyptian scarab-god symbolizing creation and renewal. This Egypt-connected iconography is even alluded to by the Prophet Isaiah as a symbol of Egypt: “Woe to the land of buzzing insect wings …” (Isaiah 18:1; csb).

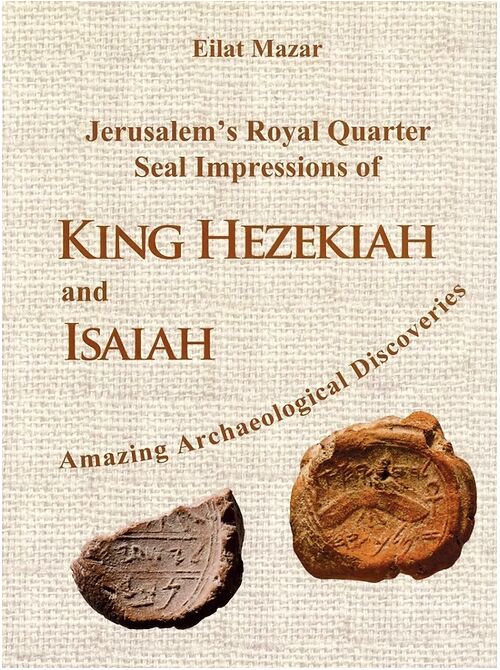

Even more overt and explicit is the use of this iconography on Hezekiah’s own royal seal. And no, I do not here refer to the famous Hezekiah bulla found during our 2009–2010 Ophel excavations, led by Dr. Eilat Mazar—the very first seal stamp of a king of Judah or Israel ever found on an archaeological excavation. That particular seal bears the motif of a sun with peculiar, downturned wings—motifs identified by Dr. Mazar as best associating with the latter part of Hezekiah’s reign (more on this further down). Instead, I refer to another personal seal of the king entirely, a handful of examples of which have appeared on the antiquities market (rather than from excavation), yet are still regarded to be authentic.

These personal seals bear exactly the same text, “Belonging to Hezekiah [son of] Ahaz, King of Judah”—but prominent is the central motif of a two-winged scarab. This is an even more closely Egypt-derived design (with the four-winged scarabs often accounted as a Phoenician variation of the Egyptian scarab symbol).

“What in the world is a two-winged dung beetle doing on a seal of a Hebrew king? Its appearance, especially on a royal seal, begs for interpretation,” wrote Prof. Meir Lubetski in his 2001 Biblical Archaeology Review article “King Hezekiah’s Seal Revisited.” “The image is a direct borrowing from Egyptian iconography and can be understood as an adaptation by the great Judahite king to advance his own national agenda. …

The name Ḫprr, or Khopri, designates the young sun god in the morning. The deity appears in a beetle guise and his chief attribute is “to become” or “to come into existence.” The amalgam fused the sense of the sun’s daily renewal with the perception of the scarab’s constant rebirth to form the Egyptian concept of life and life after death. The two wings—presumably the falcon Horus’s wings—symbolized the pharaoh’s dominion over both Upper and Lower Egypt.

What, then, did Hezekiah wish to convey by selecting an Egyptian symbol for his seal? His message becomes evident when seen in the political context of his reign. … His political alliance with the Egyptian Cushite dynasty demonstrated a daring challenge to Assyrian hegemony in the region and also reflected his direct ties with Egypt.

It’s no wonder the Prophet Isaiah’s rebuke. This overt symbolism on the king’s own personal seal is surprising—stunning, even. But Egyptian motifs are not the only telltale signs of Egyptian orientation—so too are the very names of administrative officials.

Strange Names

During the aforementioned 2009–2010 excavations at Jerusalem’s royal Ophel quarter, a large trove of bullae was discovered—34 in total. Of these, the most famous two were those belonging to Hezekiah and Isaiah. But many others in the trove were notable in their own right.

Most significant were the bullae of the “sons of Bes.” Seven such bullae were discovered among this trove, belonging to different individuals, but all of them named as a “son of Bes” in a somewhat rare third-tier section of the bullae. Bullae typically include one or two registers, with either the name of the individual at hand alone, or together with that of his father. In certain cases, there can be a third generation included, on a third register—but this is rare. In the case of the “Bes” bullae, we have a proportionately significant number of these individuals, collectively named “sons of Bes” in the third register.

Bes is a name with no known direct biblical or general Hebrew parallel. It is, however, the name of a prominent Egyptian deity—several figures of which have actually been found in Jerusalem (including on the Ophel). Though Mazar struggled with the notion that this was an outright reference to the Egyptian deity, she nevertheless suggested it may signify “a foreign name of a non-Jew who was part of the royal administration” (The Ophel Excavations to the South of the Temple Mount, 2009–2013: Final Reports, Vol. 2).

There is another notable bulla, found within the same assemblage, reading “Belonging to Ahihur.” At the top of the seal is the image of a winged falcon—the symbol of the Egyptian god Horus. Further, the name of the seal holder himself refers to this deity—a name meaning “brother of Hur”—“[t]he name Hur, originating in Egypt and related to Horus,” wrote Dr. Mazar (Jerusalem’s Royal Quarter Seal Impressions of King Hezekiah and Isaiah). She compared this name to the infamous Pashur of Jeremiah’s time, enemy of the prophet (e.g. Jeremiah 20).

What were such names and motifs doing on Jerusalem’s Ophel?

Add to that another unsavory biblical figure in Hezekiah’s administration, one of his highest-ranking palace officers: Shebna, a man described—and condemned—in Isaiah 22. In name, this individual has long been posited as another foreign official, although more likely northern in origin. The Jewish Encyclopedia gives the following assessment of this character:

The beginning of Isaiah’s denunciation, ‘What hast thou here? And whom hast thou here?’ [Isaiah 22:16] has been construed as implying that Shebna was of alien birth. But probably the meaning implied is that Shebna was an upstart or intruder. His non-Israelitish origin, however, is indicated in the kind of punishment with which he is threatened ….

Shebna favored the political connection of the kingdom of Judah with Egypt; hence it is very probable that he was taken prisoner as an enemy of the Assyrians during an invasion of the latter. The name ‘Shebna’ itself points to a non-Israelitish origin in the more northerly regions, either Phoenicia or Syria …. Probably Shebna had risen to office under King Ahaz, who favored foreign undertakings and connections.

Easton’s Bible Dictionary says Shebna “appears to have been the leader of the party who favored an alliance with Egypt against Assyria.” The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia writes: “The prophet’s language is that of personal invective, and one asks what had made him so indignant. Some (e.g. Dillmann, Delitzsch) suggest that Shebna was the leader of a pro-Egyptian party.” Isaiah 22 condemns Shebna’s wayward influence and actions and prophesies the honor of Shebna’s position passing to “Eliakim the son of Hilkiah.”

Evidently, based on biblical and extrabiblical evidence, “something is rotten in the state of Denmark”—to use the Shakespearean phrase for the Judahite administration. One wonders if this declining state of affairs and mismanagement was in any way the result of decision-making during the time of Hezekiah’s near-death illness, which occurred “[i]n those days” (2 Kings 20:1).

Meanwhile, Philistine Drama

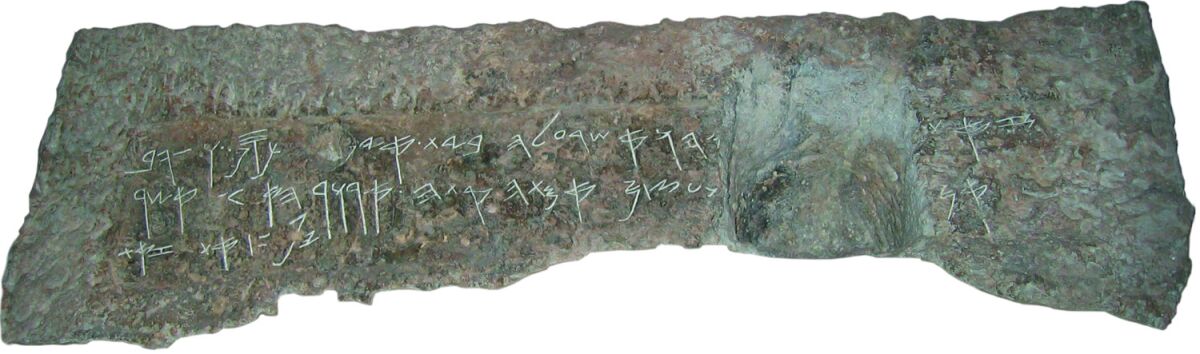

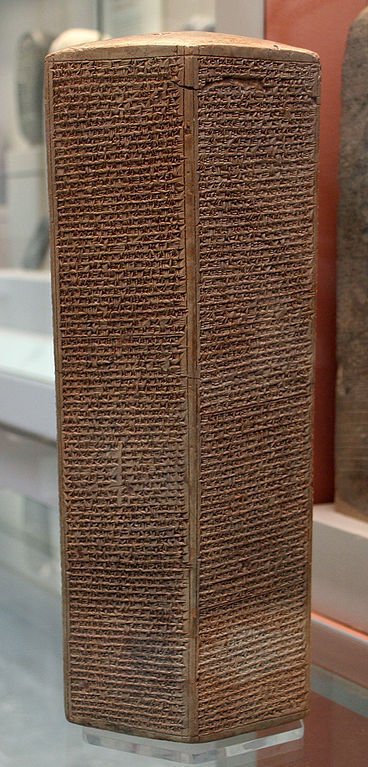

We glean further detail of another element in the story from Sennacherib, in his own inscriptions—a series of prisms relaying identical text (the Taylor Prism in the British Museum, the Jerusalem Prism in Israel, and the Oriental Institute Prism in Chicago).

In the lead-up to his account of the invasion of Judah, Sennacherib describes some particular intrigue surrounding Hezekiah and the Philistines. 2 Kings 18 records: “He [Hezekiah] smote the Philistines unto Gaza and the borders thereof, from the tower of the watchmen to the fortified city” (verse 8).

Sennacherib notes a particular Philistine king of Ekron, Padi, who was an ally of Assyria, “bound by oath and curse.” Padi had been captured and cast “into fetters of iron and given over to Hezekiah the Judahite” during the latter’s conflict with the Philistines. Subsequently, it seems that these conquered Philistines entered into the wider Egypt-oriented Levantine confederation, with the “countless host” of the Egyptians and Ethiopians at their beck and call.

Sennacherib, on the campaign trail, describes this Egyptian army coming out to fight him, which he subsequently defeated (compare Isaiah 37:8-9). From there, in describing his interactions with Hezekiah—though he never took Jerusalem, besides mentioning “caging him [Hezekiah] like a bird” in the city—Sennacherib does mention having the captive Philistine King Padi brought “out of Jerusalem.” It seems probable that this was done along with the delivery of Hezekiah’s temple-stripped tribute (2 Kings 18:14-16).

Repentance

Despite Hezekiah’s crippling payment of tribute, it soon became clear that Assyria had no intention of sparing Jerusalem. A contingent of the Assyrian army was sent with Rabshakeh to Jerusalem, camping around and surrounding the city, choking it of supplies. Word of Rabshakeh’s speech made it to Hezekiah.

Interestingly, none of Rabshakeh’s claims of Judahite reliance on Egypt are challenged. What is challenged, however, is the part of the speech concerning the God of Judah, in His alleged subservience to the Assyrians. “‘Thus saith Hezekiah: This day is a day of trouble, and of rebuke, and of contumely; for the children are come to the birth, and there is not strength to bring forth. It may be the Lord thy God will hear the words of Rab-shakeh, whom the king of Assyria his master hath sent to taunt the living God, and will rebuke the words which the Lord thy God hath heard; wherefore make prayer for the remnant that is left.’ So the servants of king Hezekiah came to Isaiah. And Isaiah said unto them: ‘Thus shall ye say to your master: Thus saith the Lord: Be not afraid of the words that thou hast heard, wherewith the servants of the king of Assyria have blasphemed Me. Behold, I will put a spirit in him, and he shall hear a rumour, and shall return unto his own land; and I will cause him to fall by the sword in his own land’” (Isaiah 37:3-6).

The rest, as they say, is history. Unlike the numerous other cities throughout the southern Levant, Jerusalem retains no late-eighth-century b.c.e. destruction layer. Sennacherib makes no mention of defeating the city, nor what happened to his men that were stationed there (men whom, according to the biblical account—and later histories—were divinely massacred in a single night—2 Kings 19:35). Sennacherib’s palatial portrayal of his campaign against Judah only depicts his conquest of the nation’s “second” city—Lachish—not the “first,” Jerusalem. And Sennacherib would go on to be summarily murdered by his own kin in his own land.

We are left with an interesting seal, however—a variant personal seal of Hezekiah, discovered on the Ophel. This seal features a central sun motif, with two peculiarly downturned wings (as opposed to the typical proud, upturned variety). Eilat Mazar identified this transformation in seal design as the later, “post-invasion/healing” symbolism of Hezekiah, with the scarab variant as the earlier. For what it’s worth, this winged sun seal does still include a lesser Egyptian element: the ankh symbol. Still, this is taken to be the ubiquitous and generic ancient symbol for “life” (in much the same way as the heart shape symbolizes “love” in our modern vernacular). In this sense, it is also seen by Mazar as an additional clue pointing to the biblical account of Hezekiah’s healing and extended life, following the invasion (Isaiah 38).

Dr. Mazar concluded regarding this bulla in The Ophel Excavations to the South of the Temple Mount, 2009–2013: Final Reports, Vol. 2:

Hezekiah changed the symbol of his authority from the beetle (four- or two-winged) … to the winged sun disk design, which represented the elevated status of the God who was the patron and guardian of his rule. On his private seal, the wings emerge from the sun disk, pointing downward, emphasizing the protection they offer to the ruler and his authority.

The significance of this symbolism is reflected in several Bible verses (Ruth 2:12; Ezekiel 16:8; Psalm 91:4). Wings, especially those of the sun, not only offer protection and coverage but also heal: ‘But unto you that fear My name Shall the sun of righteousness arise with healing in its wings …’ (Malachi 3:20 [Malachi 4:2 in other versions]).

In the words relayed by the Prophet Isaiah: “Thus saith the Lord, the God of David thy father: I have heard thy prayer, I have seen thy tears; behold, I will heal thee; on the third day thou shalt go up unto the house of the Lord. And I will add unto thy days fifteen years; and I will deliver thee and this city out of the hand of the king of Assyria; and I will defend this city for Mine own sake, and for My servant David’s sake” (2 Kings 20:5-6).