The Bible describes in grand portrayal the arrival of Jacob and his family into Egypt and their settlement in Goshen—the northeastern Delta region—as a powerful ruling family. But is there any material evidence proving the Hebrew migration into Lower Egypt?

In our January-February 2023 article “When Was the Age of the Patriarchs?”, we established the biblical chronology for the period of the patriarchs: the first half of the second millennium b.c.e., with the migration of Jacob and his family into Egypt in the early 17th century b.c.e. (see “When Was the Age of the Patriarchs?”). With this chronological biblical framework in mind, we can turn to the archaeological evidence to see if there is a fit with the arrival of Jacob and his entourage.

Not only is such a group identifiable in Egyptian history, their names are an uncanny match for Jacob and his family.

A Provincial ‘Canaanite’ Migration

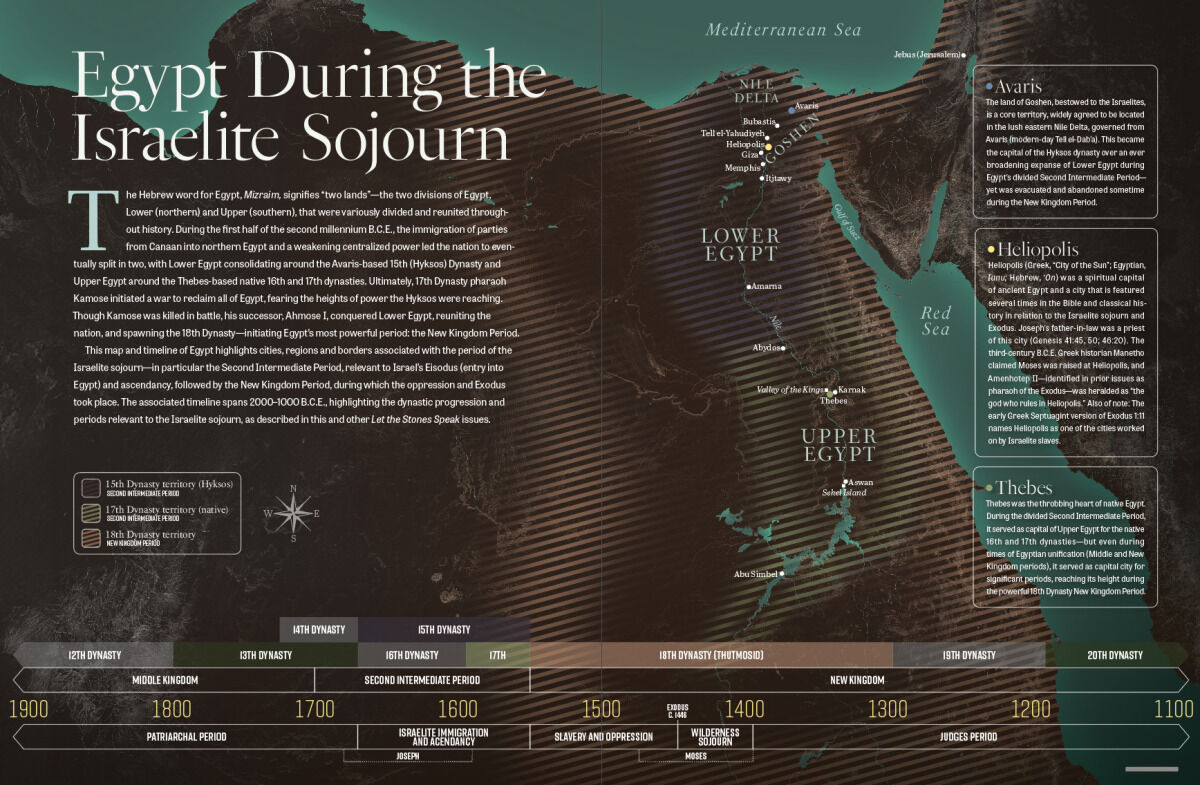

Many are familiar with Egypt’s New Kingdom Period, which began around 1550 b.c.e. and was dominated by a powerful united Egypt controlled by 18th Dynasty Thutmosid and later 19th Dynasty Ramesside pharaohs. This overall New Kingdom Period is widely regarded as the one within which the Exodus took place, with both of the two main Exodus theories fitting into this window (the “early,” 15th-century view vs. the “late,” 13th-century view; see “What Is the Correct Time Frame for the Exodus and Conquest of the Promised Land?” for more on this subject).

Before this New Kingdom Period began, however, the picture was very different. Egypt was in what is known as the Second Intermediate Period, circa 1700–1550 b.c.e. This was a decentralized period in Egyptian history, within which Egypt was essentially split in half—between Upper Egypt in the south, ruled by native Egyptian pharaohs, and Lower Egypt in the north, the swathe of Egypt including the Nile Delta and the biblical land of Goshen.

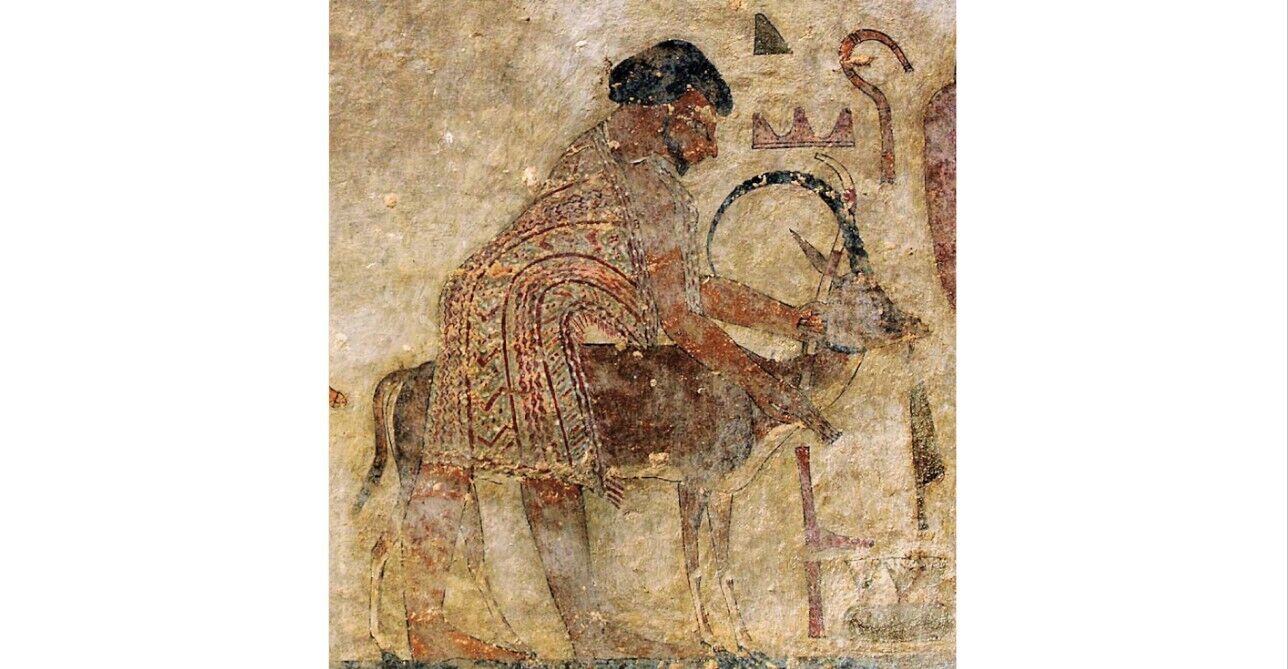

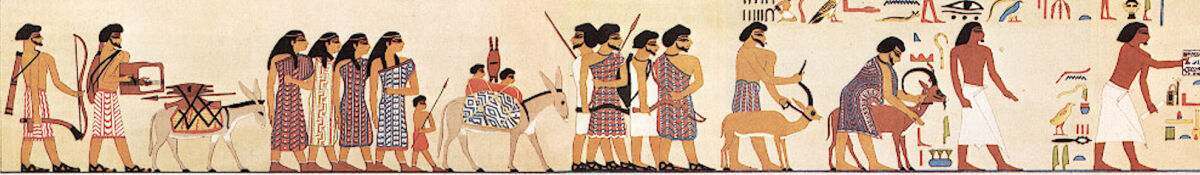

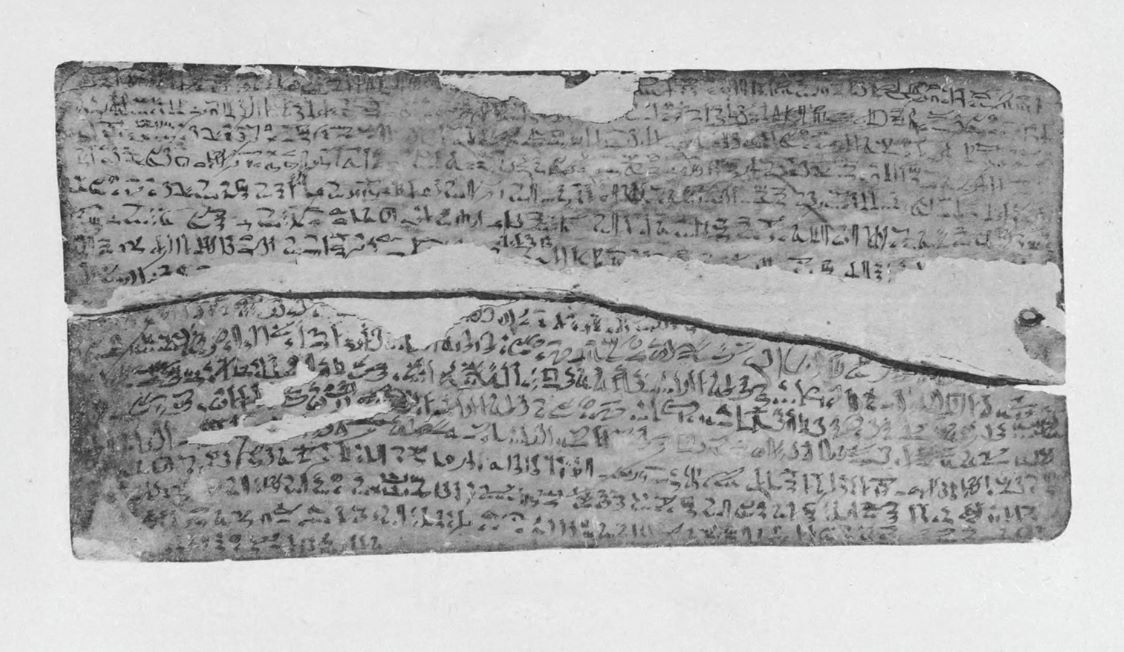

This split occurred when a population of Semitic peoples migrated from Canaan into the northern Egyptian Delta and established themselves as a powerful ruling class. These Semitic, Canaan-originating people were known to the Egyptians as the Hyksos—a unique people known for their shepherding and multicolored garments. And while later, propagandistic Egyptian texts (such as that of the third-century b.c.e. Egyptian historian Manetho) accused them of violently taking the land, modern researchers now know that they became established within Egyptian territory peaceably.

“If you study ‘fake news’ from ancient Egypt, you would consider the Hyksos a band of nasty, marauding outsiders who invaded and then brutally ruled the Nile Delta until heroic kings expelled them,” wrote Egyptologist Danielle Candelora in an article for the American Research Center in Egypt. “In fact, the Hyksos had a more diplomatic impact, contributing to progress in culture …. Rather than an ‘invasion,’ it appears that as the centralized authority of Egyptian kings declined, elites at Tell el-Dab’a [Avaris] increased their local power until, by a coup or simply a slow, peaceful process, they took the Heka Khasut [Hyksos] title and became kings in their own right” (“The Hyksos”). The Hyksos, when referred to generally (as in this article), represent what is known as Egypt’s 15th Dynasty, circa 1670–1550 b.c.e. (Note that there is an earlier, 14th Dynasty also sometimes classified as “Hyksos,” or referred to in terms of “Lesser Hyksos”—see our article, “Who Was Joseph’s Pharaoh”—although the definition and dating of this dynasty is much more controversial.)

The 15th Dynasty Hyksos continued to live and self-govern for little more than a century in the northern Delta region of Egypt until a series of native Egyptian pharaohs from Upper Egypt rose up. They accused the Hyksos of overrunning Egypt and eventually overthrew them. The Hyksos, according to Manetho, “took their journey from Egypt, through the wilderness [and] they built a city in that country which is now called Judea, and that large enough to contain this great number of men, and called it Jerusalem” (as quoted by the first-century c.e. Jewish historian Josephus in Against Apion, 1.14).

The association of these Hyksos with the Israelites, therefore, is not uncommon. After all, depending on the chronology used, this dynasty was established in Egypt around the same time as the biblical immigration of Jacob and his family. By the same token though, unsurprisingly, it is not popular in academia to identify the Hyksos outright as Israelites. The term Canaanites—based on their point of origin, prior to arriving in Egypt—is used much more freely. (As one leading Hyksos scholar stated, based on the West Semitic language and territorial origin of the Hyksos, they “may be called for convenience [sic] sake Canaanites.”) Still, the term “proto-Israelites” is sometimes used in this debate.

In a Jerusalem Post article, one Egyptologist was cited dismissing the connection between the Hyksos and the Israelites, condemning those looking for such historic connections with the biblical text because “the [biblical] text is not to be taken literally.” Remarkably, however, she admitted that “[t]he concept has been frozen in the Egyptian memory to the point that to this day, the average person in Egypt thinks the Hyksos were Jews and associates them with destruction and chaos” (“Enigmatic Hyksos Did Not Invade Egypt, Were Not Israelites, Scholars Say,” 2020; emphasis added throughout).

How well do the Hyksos fit with the establishment of Jacob’s family in Egypt? And despite the comparatively piecemeal evidence for the reign of the Hyksos—which is unsurprising, considering later Egyptian rulers sought to blot out their history—can any individuals actually be positively identified as members of Jacob’s family?

‘Shepherd Kings’

First the name, Hyksos. Some may wonder why this group was not called Israelites if that is indeed their identity. Actually, this terminology is found more often later in the Bible. The term “Hebrews” is more often used than “Israelites,” right up until the time of the settlement in Canaan on the other side of the Exodus. Of course, the patriarch Jacob was renamed Israel (Genesis 32:28-29). But naturally, his sons wouldn’t have immediately borne and used the title, “Israelites.” Often, such patronymic titles take hold several generations later. (Even still, during the later monarchic period, foreign nations often used different terminology than “Israel” or “Israelite,” instead preferring to use the title of its ruling dynasty for the nation—e.g. “House of Omri” and “House of David.”)

The term Hyksos first began as an Egyptian appellation, and it is actually first found as early as the mid-19th century b.c.e.—some 200 years prior—on the tomb-wall painting of Khnumhotep ii, depicting an entourage of men and women in brightly colored garments (as pictured above. Interestingly, following the same aforementioned biblical chronology, this would be around the time in which Abraham began making his pilgrimages into Egypt with his entourage). A fairly standard view is that the Hyksos migrants themselves eventually adopted this as their official dynastic title while in Egypt (see, for example, Candelora’s article “Defining the Hyksos: A Reevaluation of the Title hk3 h3swt and Its Implications for Hyksos Identity”).

Josephus, for his part, quoting Manetho, asserts this name to mean “shepherd kings.” From his tome Against Apion: “This whole nation was styled Hycsos, that is, Shepherd-kings: for the first syllable Hyc, according to the sacred dialect, denotes a king, as is Sos a shepherd; but this according to the ordinary dialect; and of these is compounded Hycsos” (ibid).

The standard modern interpretation of the name Hyksos among Egyptologists is as “foreign kings,” rather than “shepherd kings” (with scholars believing Josephus or Manetho misinterpreted the word). Nevertheless, the ancient Egyptian historian Manetho—whose work, now lost, is quoted by Josephus—described these people chiefly as a shepherding population. Again from Josephus, quoting Manetho directly: “(But Manetho goes on): ‘These people, whom we have before named kings, and called shepherds also, and their descendants,’ as he says, ‘kept possession of Egypt ….’ [Afterward], he says, ‘That the kings of Thebais and the other parts of Egypt made an insurrection against the shepherds’ ….

“Now Manetho, in another book of his, says, ‘That this nation, thus called Shepherds, were also called Captives, in their sacred books.’ And this account of his is the truth; for feeding of sheep was the employment of our forefathers in the most ancient ages and as they led such a wandering life in feeding sheep, they were called Shepherds.”

Josephus continued at length to make the case that the Hyksos were, indeed, none other than his Israelite forebears.

This accords well with the biblical account. Jacob’s family, when they were brought into Egypt, were known primarily for their shepherding. “And Pharaoh said unto his [Joseph’s] brethren: ‘What is your occupation?’ And they said unto Pharaoh: ‘Thy servants are shepherds, both we, and our fathers.’ And they said unto Pharaoh: ‘To sojourn in the land are we come; for there is no pasture for thy servants’ flocks ….’” (Genesis 47:3-4). The pharaoh proceeded to turn over land to Jacob’s family in the northern Delta territory of Goshen.

The capital city of the Hyksos was called Avaris. Again, quoting Manetho, Josephus relayed that Avaris was the “ancient city and country” of the shepherds, “given” to them within Egypt. This site is identified as the modern-day ruins of Tell el-Dab’a. Archaeological excavations over the past century and a half have revealed evidence of a clearly foreign, Semitic population, with housing styles similar to those in Canaan, along with Levantine-style weapons and pottery. Archaeologists have also found sacrificial remains, notably excluding pig, leading excavators to speculate some form of “kosher” system was in place. Large food-storage silos were also discovered at the site.

But what of Jacob and his immediate family? Is it possible to identify any individuals among the Hyksos ruling class? This is where things get especially interesting.

Jacob

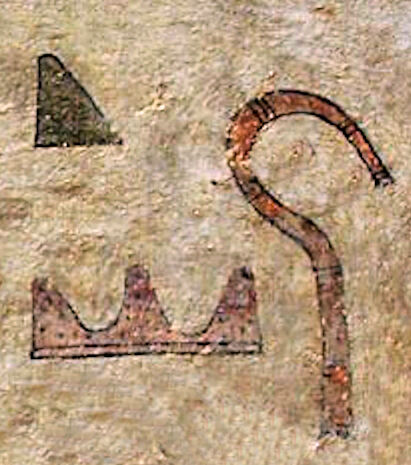

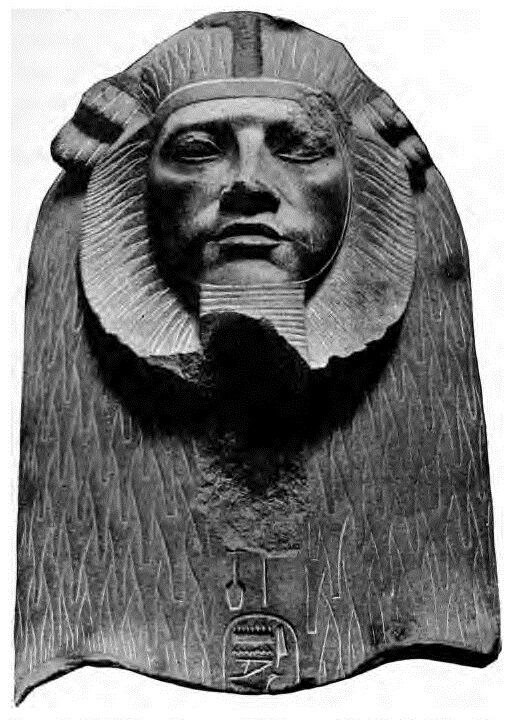

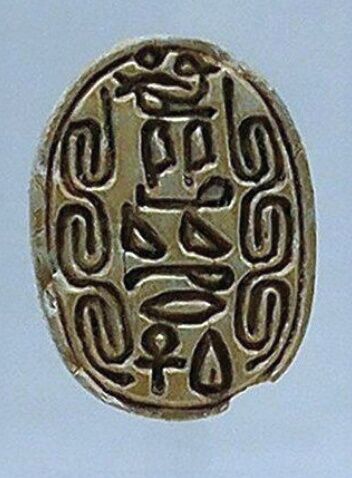

Very little is known about the Hyksos rulers. Not only is there significant debate about the order in which they ruled and how many there were, there is debate about whether or not certain of these Hyksos leaders ruled as “pharaohs” in their own right, or simply constituted high-ranking figures. One of these especially prominent Hyksos individuals is a man known from nearly 30 royal scarab seals found both in Canaan and Egypt. These scarabs, believed to date to the 17th century b.c.e., bear the name Yaqub-har.

Yaqub is the exact transliteration of the Semitic name Jacob.

The Bible shows Jacob was a highly respected leader, not only in Canaan but also in Egypt. When he died, he underwent a 40-day embalming process and was mourned by the Egyptians for 70 days (Genesis 50:1-3; this description of the mummification-to-burial process, including 40 days of packing and preserving the internal organs and body, is a well-known Egyptian procedure). As with Joseph, Jacob’s body was returned and buried within Canaan.

The “har” in Yaqub-har is a Semitic word that can mean hill, mount or mountain. This word is actually connected with Jacob several times in the Bible (e.g. Genesis 31:25, 54; Isaiah 2:3). It may have even constituted some kind of a familial element among the Hyksos—as is also attested by the next name of interest.

Issachar

A single inscription, found on a doorjamb at Avaris, reveals another of the early Hyksos leaders. This individual’s name, similarly suffixed, is Sakir-har. The word sakir means “reward,” with the “har” element again matching that of Yaqub-har.

This name closely parallels that of Jacob’s son Issachar.

The biblical name Issachar, or Is-Sakir, means “there is a reward.” The Bible relates that his mother, Leah, proclaimed when she bore him: “God has granted me a reward [sakar] …. So she named him Issachar” (Genesis 30:18; New English Translation).

Joseph

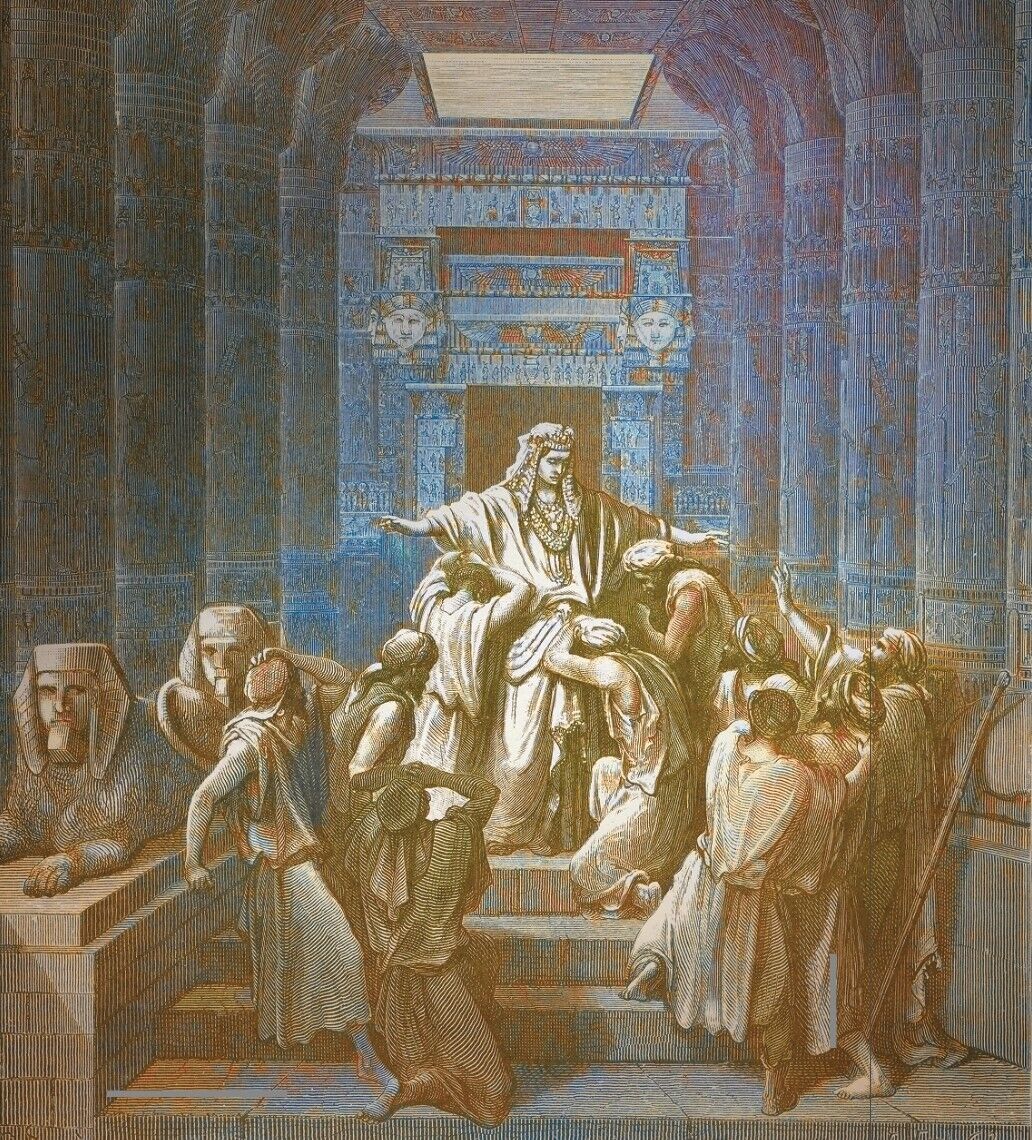

But what about Joseph? As the Bible recounts, he was the first of his family established within Egypt and was, of course, the individual afforded the initial rulership of the nation as second-in-command of Egypt under the native pharaoh. “And Pharaoh said unto Joseph: ‘See, I have set thee over all the land of Egypt.’ … ‘[O]nly in the throne will I be greater than thou’” (Genesis 41:41, 40).

Besides other prominent names highlighted by archaeology (such as the two above), the Egyptian historian Manetho enumerated six official Hyksos “rulers.” This is what he wrote of the very first one that came to power in Egypt: “At length they [the Hyksos] made one of themselves king, whose name was Salatis; he also lived at Memphis, and made both the upper and lower regions pay tribute …. Thither Salatis came in summer time, partly to gather his corn” (Against Apion, 1.14). This “corn-gathering” is an interesting tidbit, relating to the biblical account: “And Joseph gathered corn as the sand of the sea, very much …” (Genesis 41:49; King James Version).

Manetho’s first Hyksos “king,” Salatis (variously “Salitus” or “Salitis”), may seem at first to have nothing to do with the biblical Joseph in name. But the name Salitis is of particular note.

First, note that both the Classical writers Manetho and Josephus wrote in Greek. In this language, masculine names often have an added -is ending. This is the case with their naming of other such pharaohs or leaders—an -is ending added (such as for the Hyksos ruler Apophis, known in original Egyptian form as Apep or Apepi), a suffix not originally part of the name. So we can strike this from our name Salit-is.

In the Bible, Joseph is called the “governor” of Egypt. “And Joseph was the governor over the land …” (Genesis 42:6). The word here translated “governor” is unique, entirely different from that used dozens of times elsewhere throughout the Bible for different governing individuals. The title here is Salit—thus naming him “Joseph the Salit”—an uncanny match for Manetho’s first Hyksos “king” Salit, or Salitis.

Benjamin

After Salitis, the second Hyksos ruler recorded by Manetho is Bnon/Benon. If we identify the first Hyksos leader Salitis as Joseph—while recognizing other “leading” brothers on the scene at the same time—it is logical to believe that the next in line was Joseph’s only full brother. This would be the youngest of Jacob’s 12 sons, Benjamin. The Bible relates in some detail the level of Joseph’s public honoring of Benjamin in the Egyptian court. He received five times the portion of food as the other brothers (Genesis 43:34), five times the amount of royal apparel and great riches (Genesis 45:22).

There is some face-value degree of similarity to the names Benjamin and Benon, but there is another, much more striking connection. A lesser-known fact is that Benjamin actually had two names—Benjamin being his second, given to him by his father (and a play on his first name).

Benjamin’s first name was given to him by his mother, Rachel, who died soon after childbirth. “And it came to pass, as her soul was in departing—for she died—that she called his name Benoni; but his father called him Benjamin” (Genesis 35:18). The name Benoni—a veritable match for the second Hyksos king Benon—literally means “son of my sorrow.”

The list could go on. What about one of the later Hyksos leaders, Khyan? Amos 5:25-26 mention the peculiar name Chiun (Kiyun) in the context of the Israelite Exodus.

Then there’s Semqen/Shemqon. This Hyksos leader is known from a single scarab seal found at Tell el-Yahudiyeh (interestingly, a site in Lower Egypt whose name means “the Jewish mound”). The initial Semitic shem- element is immediately recognizable. But could this perhaps be a link to the biblical Simeon? Again, there is more than meets the eye with this name.

Between the m and the n in Simeon (pronounced in modern Hebrew more like “Shem’on”) is a glottal-stop letter (ע) for which there is no equivalent in English (and the original sound of which has also been lost to modern Hebrew). It’s the same letter, for example, that starts the name of the biblical king Omri—a name transliterated in ancient Assyrian inscriptions as Kumri. If this letter was originally pronounced in such a way, is it in the realm of possibility that Shemqon and Simeon (Shem[k]on) are one and the same individual?

We do not as yet have absolute proof that these above-mentioned individuals were the same as those mentioned in the Bible. We don’t have reams of knowledge about the Hyksos rulers, thanks mainly to later Egyptian pharaohs who sought to eradicate their memory.

But is it all just coincidence? We have a powerful Semitic, shepherd-centric dynasty that moved from Canaan into the Egyptian Delta—the biblical region of Goshen—in the 17th century b.c.e. We have a dynasty whose leading individuals match closely with the names or titles of Jacob and his sons. And we have a nation, according to Manetho, who also came to be “called Captives, in their sacred books.” What kind of “captives” were these, if not the Israelites? And what were their “sacred books,” if not the holy scriptures?

How Powerful Were the Israelites?

The Hyksos became a formidable group within Egypt. They experienced a peculiar, sharp rise to power in the north of the nation, which escalated to a peak of dominance that some argue surpassed even that of the native pharaohs ruling from the south of Egypt. But does this picture accord with the biblical account of the family of Jacob? One Hyksos expert states that the identification of the Hyksos as Israelites should be ruled out because the Hyksos “experienced the glory of controlling the Delta and a part of the Nile valley for over 100 years. However, this is in no way in keeping with the tradition of the Israelites and their experience of oppression in Egypt” (“On the Historicity of the Exodus: What Egyptology Today Can Contribute to Assessing the Biblical Account of the Sojourn in Egypt”).

The Bible does say the Israelites experienced oppression and slavery in Egypt. But it also records that before this they experienced a period of abundance and power!

Recall Exodus 1:1-10, which describe how the Israelites had become “fruitful, and increased abundantly, and multiplied, and waxed exceeding mighty; and the land was filled with them” (verse 7). It was only much later that the Israelites were overthrown and enslaved by a “new king over Egypt, who knew not Joseph. And he said unto his people: ‘Behold, the people of the children of Israel are too many and too mighty for us; come, let us deal wisely with them …” (verses 8-10). Biblical chronology has Joseph beginning to rule at around 30 years old and dying at 110. Thus, if this “new king” “knew not Joseph,” it would stand to reason that this would be at a bare minimum 80 years after the patriarch had first come to power.

There could perhaps be a tendency to view Jacob’s family as more or less an insignificant group of humble shepherds quickly overwhelmed within the melee that was ancient Egypt. But even from the outset of their “Eisodus” (entry into Egypt), this was no insignificant group of people. They were, in their own right, a powerful force to be reckoned with.

In Canaan, Isaac’s power and influence—his land holdings and vast number of shepherds, retainers and other workmen—were so significant, the king of the Philistines sent him and his entourage away: “for thou [Isaac and company] art much mightier than we” (Genesis 26:16). Isaac had only two recorded sons (Esau and Jacob). One can only imagine how large and influential the family grew under Jacob and his 12 sons.

Note also the total destruction of the powerful Canaanite city Shechem at the hands of only two of Jacob’s sons, Simeon and Levi, in revenge for the shame brought upon their sister Dinah (Genesis 34). This was a retribution certainly led by these individuals, but undoubtedly with the support of their workmen.

In this same vein, the patriarch Abraham had 318 “trained men, born in his house” (Genesis 14:14)—before he had any sons of his own—whom he rallied to beat back a coalition of armies attacking Canaan. And the personal differences between Jacob and his brother Esau very nearly led not to a single hand-to-hand combat between them, but to all-out war between their large entourages (Genesis 32-33)—Esau fielding a band of 400 men.

Abraham, Isaac, Jacob and his sons were not monkish ascetics or vagrants. They were powerful leaders over significant populations of people for the time. In his book The Moses Connection, author James Jordan speculates that Jacob’s total entourage in descending down into Egypt could have numbered as many as 10,000 individuals. Other theories posit “several thousands” (e.g. History of the Old Covenant, Vol. 2).

All this fits well with the picture painted of the Hyksos: This was a civilization in its own right, living within Egypt, powerful in might. Of course, it does not mean that all Hyksos were Israelites, that is, full-blood descendants of Jacob/Israel. In fact, archaeologists have uncovered evidence of some degree of “multiculturalism” among the Hyksos community. But here again, the Bible reveals that at the time of the Exodus, along with the Israelites, a “mixed multitude went up also with them” (Exodus 12:38). The same chapter also contains provisions for those of other nations seeking to become part of the “congregation of Israel.”

But How Monotheistic?

Another argument sometimes used to reject the identification of the Hyksos as Israelites is the claim that Jacob’s family were righteous monotheists. This was highlighted a number of years ago by a Haaretz journalist in an article titled “For You Were (Not) Slaves in Egypt.” The author dismissed the historicity of the Israelites in Egypt due to a lack of archaeological evidence for a yhwh-worshiping community (though this statement should be viewed in light of Exodus 6:3).

Certainly, as the Bible reveals, the patriarchs themselves maintained a monotheistic loyalty to the God of the Bible, but that is more than can be said of their families—even their wives. Genesis 35:2 mentions Jacob’s attempt to remove “strange gods” from among those of his household. Genesis 31 even describes Jacob’s wife Rachel stealing away the gods of her father, Laban.

The Hyksos were known for a degree of monotheism—something unusual in Egypt at the time. Yet Joshua himself notes the idolatry of the Israelites during their sojourn in Egypt (Joshua 24:14). The Hyksos, for their part, are known for a reverence toward “Seth,” and evidence of a degree of Canaanite Baal worship has also been found among their ranks.

This is actually another interesting connection between the Hyksos and the Israelites. One of the chief symbols of Baal is the bull. Recall that the Israelites, after being freed from captivity, built and worshiped a golden calf: “This is thy god, O Israel, which brought thee up out of the land of Egypt’” (Exodus 32:4). This bull/calf motif persistently crops up in Israelite worship. During the period of the judges, Gideon slaughtered the bulls of Baal (Judges 6). Later, King Jeroboam established two golden calves for worship once again—idols that were named as “thy gods, O Israel, which brought thee up out of the land of Egypt’” (1 Kings 12:28).

Was this bull/calf god merely an arbitrary Egyptian deity picked up by the Israelites while they were in Egypt? This is a popular explanation. But perhaps it doesn’t sufficiently explain the consistency of the Israelites’ worship of it and, in particular, its role as “deliverer” from Egypt. Was this, perhaps, a Canaanite or Syrian god that had already been historically worshiped by certain among Israel’s royal ranks—first picked up while in Canaan (or even earlier, in Syria) and continuing to be venerated as a god of the Hyksos later on during the height of their prosperity—hence the post-Exodus identification of this god as their original own god, the one who brought them out of Egypt?

Manetho at least includes an interesting detail about the early Hyksos at the time of their arrival in Egypt: They “demolished the temples of the gods” (Against Apion, 1.14).

But Weren’t the Hyksos Driven Out Too Early?

There is one final question about the association of the Hyksos with the Israelites. At face value, Manetho appears to infer that following the overthrow of the Hyksos (circa 1550 b.c.e.), they were immediately driven by the Egyptians into Canaan, where they established the Israelite nation with Jerusalem as its capital. Actually, Manetho somewhat confusingly appears to describe two “exoduses.” The second, long after the overthrow and expulsion of the Hyksos, allegedly took place when an Egyptian priest dually named “Osarsiph” and “Moses” rose up to free a band of 80,000 slaves together with 200,000 Hyksos.

Much has been made of the propagandistic (and even clearly anti-Semitic) nature of Manetho’s text—although in many ways, it does constitute a more-than-suspicious admission of the Exodus account. And even though Manetho’s account of the Hyksos is the most complete, early Egyptian account we have, the fact remains that it was composed over a millennium after the events it describes and is only preserved in secondhand quotations.

Dr. Manfred Bietak, chief excavator of Tell el-Dab’a (Avaris), is one of the foremost experts on the Hyksos. He states that despite Manetho’s overly simplistic claim that the Hyksos were expelled to Canaan following their defeat in the mid-16th century b.c.e., there is no archaeological evidence for this. “[W]e have no evidence that the Western Asiatic population who carried the Hyksos rule in Egypt was expelled to the Levant,” he wrote in his article “From Where Came the Hyksos and Where Did They Go?” Instead, following their defeat, “there is mounting evidence to suggest that a large part of this population stayed in Egypt and served their new overlords in various capacities.” Evidence of this can be found throughout Egypt, including an “uninterrupted” production of Hyksos-style pottery in the Eastern Delta, as well as a degree of continued worship of “Canaanite cults.”

This archaeological data, then, fits more closely with the biblical account of the Israelites being overthrown by the native Egyptian pharaoh and set to work on various production and construction jobs around Egypt, probably in conditions of worsening severity. This, followed by a later Exodus event—one that does fit with archaeological evidence from a time of upheaval in Canaan, not from the mid-16th-century b.c.e. period of a “Hyksos overthrow,” but roughly 150 to 200 years later—matching archaeological evidence of an abandonment of Avaris at this time.

The overall picture revealed by archaeology of the period of Hyksos rule, then, fits remarkably well with the biblical account and chronology of the descent of Jacob and his family into Egypt.

Can we pick up this population on the other side of the sojourn—after the Exodus? We can—but that’s another article for another issue.

Further Reading:

The Amarna Letters: Proof of Israel’s Invasion of Canaan?