The biblical story of Joseph is a literary masterpiece. The tale of an innocent boy, sold into slavery by jealous older half-brothers, who grows up to become the second-most powerful person in the kingdom of Egypt—the account is filled with family drama, strange dreams, plot twists and profound lessons about faith, patience and forgiveness. The 18th-century French philosopher Voltaire regarded it as one of the most precious narratives handed down from antiquity.

Many Bible scholars consider the story of Joseph to be the most unified narrative in the Hebrew Bible. The plot builds in chiastic structure through six successive episodes until the climax where the mysterious vizier tells his long-lost brothers that he is the boy they sold into slavery all those years ago. Then, after the dramatic reveal, the story winds down through another six episodes until Joseph dies surrounded by his grandchildren.

Westminster College professor John Skinner calls the Joseph narrative “the most artistic and most fascinating of the Old Testament biographies.” This tale weaves pattern into meaning so effectively, that it is taken for granted by many historians and theologians that it must reflect a work of fiction.

Yet just because a story is masterfully recorded does not mean that it is untrue. On the contrary, certain details reflecting the Egyptian background of this story actually reveal the historicity of the account—and even the identity of a particular pharaoh.

Dating Joseph’s Story

Most fairy tales begin with “a long time ago” or “once upon a time.” The story of Joseph, however, does not. The Bible goes into some detail to tell us exactly when and where this story takes place.

The Bible says the Exodus occurred 480 years before the construction of Solomon’s temple (1 Kings 6:1). With the temple built in the first half of the 10th century b.c.e. (or more specifically, the broadly agreed-upon date of 967 b.c.e.), this puts the Exodus somewhere within the mid-15th century b.c.e. (circa 1446 b.c.e.).

Working back from this date, the calculation of various internal biblical figures reveals the sojourn in Egypt—from the time of the descent of Jacob’s family—to have lasted just over two centuries. This accords with Genesis 15:16, which states that the Exodus would include Israelites of the fourth generation from those who entered (something affirmed by several of the genealogies of the older Exodus personalities mentioned). It also accords with Galatians 3:16-18, which adds further detail—that the Exodus occurred 430 years after God’s covenant with Abraham, thus putting the descent of Jacob and his family, and therefore the Joseph account, chronologically roughly halfway between.

Without getting entrenched too much into debate about specific dates, this would at least generally put Joseph on the scene in Egypt within the first half of the 17th century b.c.e. (This topic of chronology is, unsurprisingly, one of considerable discussion and debate; for more detail, see our article “When Was the Age of the Patriarchs?”) Notably, based on parallels in the historical context, this is where many biblical scholars place the time frame of Joseph’s story—within Egypt’s Second Intermediate Period, circa 1700–1550 b.c.e. One reason for this, for example, is that the Joseph story prominently features chariots (e.g. Genesis 41:43; 46:29; 50:9). The use of chariots in Egypt is widely recognized as beginning around the start of the Second Intermediate/Hyksos Period with the earliest material evidence dated to the 17th century b.c.e.

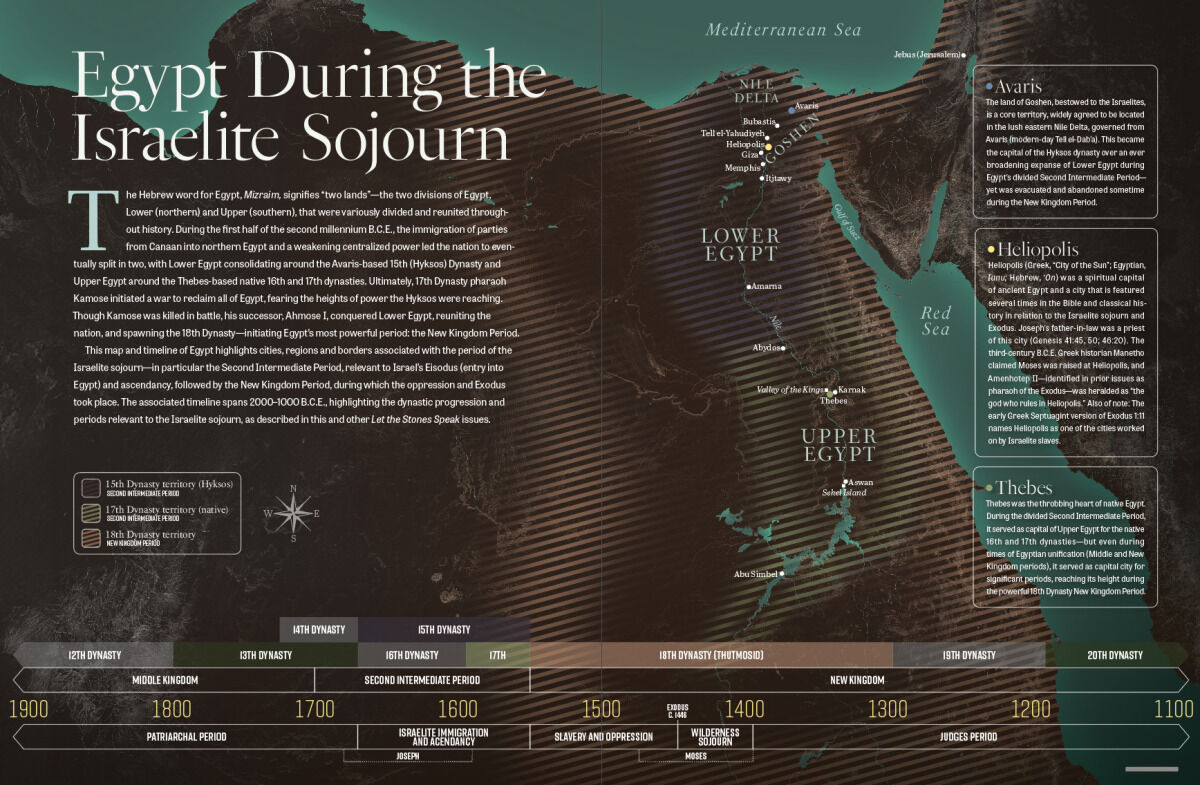

Egyptologists divide ancient Egyptian history into three main periods in which the kingdom was unified under the rule of a powerful pharaoh: the Old Kingdom Period, the Middle Kingdom Period and the New Kingdom Period. These periods are separated by intermediate periods when Egypt was divided between two or more pharaohs. The Second Intermediate Period begins around the start of the 17th century b.c.e., when the last pharaoh of the Middle Kingdom Period moved his capital city from Itjtawy to Thebes—allowing a new dynasty of Semitic rulers to govern the Nile Delta.

Comparing the biblical narrative with the archaeological record, Joseph would have been sold into slavery during the latter part of Egypt’s 13th Dynasty. This dynasty was a direct continuation of the powerful 12th Dynasty, which ruled all of Egypt during the 20th to 19th centuries b.c.e. Yet Egyptologists refer to the 13th Dynasty as separate to highlight the fact that the Egyptian pharaohs were losing control of the Nile Delta to the arrival of Canaanite immigrants from the Levant, sometimes referred to collectively as the Lesser Hyksos. These Canaanites formed what is known as the 14th Dynasty, on the scene concurrently with the native 13th Dynasty. As we will see, this setting is of particular relevance to our biblical account.

Placing Joseph’s Story

In addition to emphasizing the “when” of Joseph’s story, the Bible goes to great lengths to establish the “where.” Abraham, Isaac and Jacob all pitched their tents on the Plain of Mamre, near Hebron (Genesis 13:18; 23:2,19; 35:27). Yet Jacob’s sons often went north to Shechem to graze their flocks (Genesis 37:14).

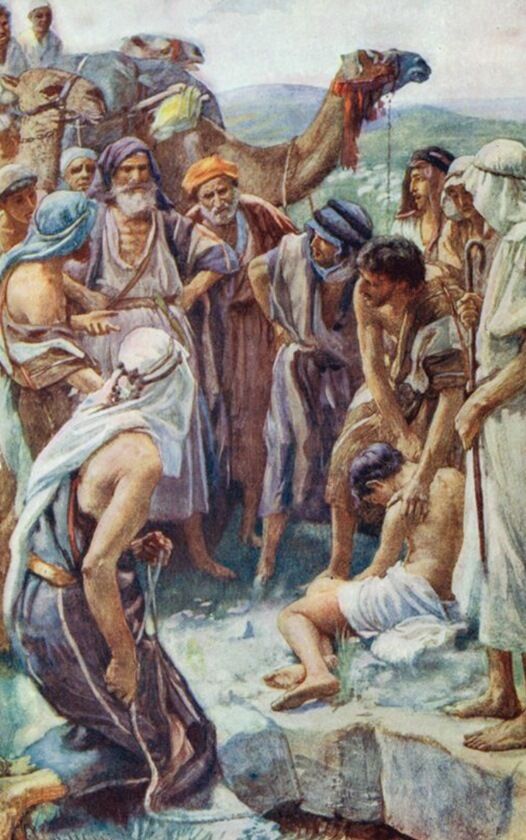

It was just north of Shechem, near the town of Dothan, that Joseph’s brothers sold him into slavery. Verse 25 notes that after Joseph’s jealous brothers threw him in an empty well, they “lifted up their eyes and looked, and, behold, a caravan of Ishmaelites came from Gilead, with their camels bearing spicery and balm and ladanum, going to carry it down to Egypt.” This is another important detail relevant to questions on the historicity of the narrative.

During the Egyptian Middle Kingdom Period, most trade with Canaan was carried out via ship. Maritime contact was strong with the city of Byblos, which imported so much papyrus that the Greek word for “book,” biblio, is derived from the city (and is in turn where our English word Bible originates). Yet trade patterns changed with the rise of the Lesser Hyksos in the Nile Delta.

According to Dr. Daphna Ben-Tor, curator of Egyptian Archaeology at the Israel Museum, maritime trade between Egypt and Byblos ceased around the 17th century b.c.e. (“The Sealings From the Administrative Unit at Tell Edfu,” 2014). This maritime trade was replaced by overland trade caravans between Canaan and the Nile Delta.

So when Genesis 37 recounts that Joseph’s brothers sold him to a caravan of Ishmaelites traveling from Gilead to Egypt, it is not recounting a strange thing. A century earlier, goods such as spices, balm and ladanum might have been dropped off in Byblos for shipment to Egypt. But by the time of Joseph, trade from Canaan to Egypt was largely caravan-based. And if Joseph’s brothers had not spotted the initial Ishmaelite caravan, they would not have had to wait very long before another such caravan appeared on the horizon—Dothan was near a major trade artery.

The late Egyptologist Prof. Kenneth Kitchen drew attention to the fact that Joseph’s sale price of 20 shekels of silver was the standard slave price in the 18th–17th century b.c.e., as reflected in a number of ancient inscriptions from this period. “[I]n earlier times … 10 shekels was the commonest price …. After the 18th/17th centuries, prices duly rose,” he noted, with an inflated “average [that] crept up to 30 shekels and more” (On the Reliability of the Old Testament). The Bible’s claim that Joseph’s brothers sold him for 20 shekels silver fits perfectly within this particular historical context.

These Ishmaelites would then likely have proceeded along the Way of Horus until they reached the courts of Potiphar, captain of pharaoh’s guard. Despite the attempts of some to paint Joseph’s sale and servitude to a northern Hyksos ruler, the Bible indicates the opposite—that the pharaoh of Joseph was a native Egyptian!

Talk Like an Egyptian

The 13th Dynasty of Egypt is generally accounted as beginning when Queen Sobekneferu, daughter of Amenemhat iii, allowed the Lesser Hyksos to establish themselves in the eastern Nile Delta. Yet the pharaohs of the 13th Dynasty did not abandon the Nile Delta completely. Rather, they ruled from the city of Itjtawy, located in the southern Nile Delta, until the early 17th-century b.c.e. pharaoh Merneferre Ay moved his capital south to Thebes.

A great deal of internal biblical evidence suggests that the pharaoh Joseph served under was a native Egyptian.

An example is the Bible’s emphatic repetition—including three times in just five verses—that Potiphar was an “Egyptian” (Genesis 39:1, 2, 5). This at first seems redundant—until viewed in the light of the establishment of the Lesser Hyksos in Lower Egypt. Other relevant Bible passages include Genesis 43:32 and 46:34, the latter of which states that “every shepherd is an abomination unto the Egyptians”—yet this was the practice of the Hyksos, whom many ancient authors refer to as the “shepherd kings.” Such passages only make sense if Joseph was serving in the court of a native Egyptian pharaoh of the 13th Dynasty. In the words of Professor Kitchen: “The careful speculation (Genesis 39:1) that Joseph’s first boss Potiphar was an Egyptian—surely, one would expect him to be Egyptian in Egypt!—suggests that Egyptians were not the sole population in the East Delta” (ibid).

The kicker is that Joseph, in seeking to conceal his identity from his brothers, pretended not to understand the Semitic language of the Levant, and instead spoke through an interpreter. “And they knew not that Joseph understood them; for the interpreter was between them” (Genesis 42:23). This ruse only makes perfect sense if Joseph’s brothers were interacting with a vizier reporting to a native Egyptian pharaoh, in the native Egyptian language—not the Semitic language of the Hyksos.

Another piece of evidence indicating Joseph served a 13th Dynasty pharaoh is the fact that the pharaoh arranged Joseph’s marriage to Asenath, daughter of the priest of On (better known as Heliopolis; Genesis 41:45). Egyptologist Prof. Kim Ryholt estimates that the Lesser Hyksos never exerted control further south than the city of Athribis, so only a pharaoh from the 13th Dynasty would have had the authority to arrange a marriage between Joseph and an official in Heliopolis.

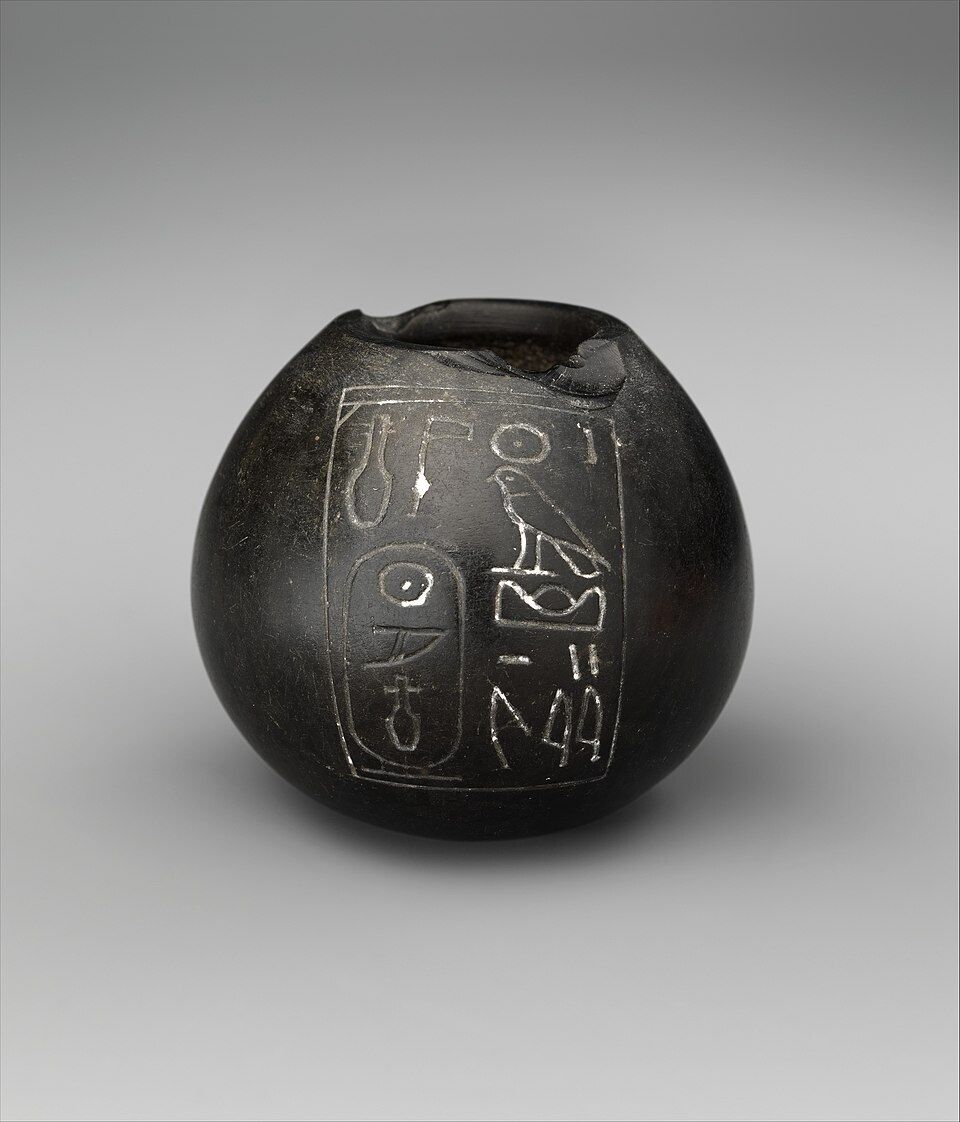

Two scarabs bearing the name of the aforementioned Merneferre Ay have been discovered in Heliopolis, so we know that the 13th Dynasty did maintain a presence there into the 17th century. In fact, Merneferre Ay was the very last native Egyptian pharaoh to leave scarabs behind for us to find in the Nile Delta until the rise of the New Kingdom Period, nearly a century and a half later.

Introducing Merneferre Ay

The 13th Dynasty endured for roughly 150 years (circa 1800–1650 b.c.e.), but much of that time was marred by turmoil, while the Lesser Hyksos began to carve out for themselves a semi-autonomous state. Within that time frame, there is evidence of more than 54 pharaohs, putting an average regnal length at about only three years. Only four 13th Dynasty pharaohs are known to have reigned longer than 10 years: Neferhotep i, Sobekhotep iv, Wahibre Ibiau and Merneferre Ay. This is important because the biblical account reveals that the pharaoh Joseph served under ruled for longer than 10 years.

The first time Joseph’s pharaoh is explicitly mentioned is in Genesis 40:2. This verse recounts how the pharaoh threw his butler and baker into prison, where they met Joseph, who interpreted their strange dreams about their futures: Joseph informed the butler that he would be released in three days; the baker, that he would be hung in three days.

Joseph’s interpretation came true; yet the butler forgot to ask the pharaoh for Joseph’s release (verse 23). When pharaoh had his own strange dream two years later, the butler told him about the man he met in prison. The account gives every indication that this was the same pharaoh who had imprisoned his butler, and the same pharaoh who later promoted Joseph following the interpretation of his own dream. Pharaoh’s dream, Joseph explained, meant there would be seven years of plenty followed by seven years of famine. Jacob and his family arrived in Egypt during the second year of the famine, and there is no indication the pharaoh had died and was succeeded during this nine-year time period.

Combining the two years that elapsed between the butler’s dream and pharaoh’s dream with the nine years Joseph served as vizier for this pharaoh before Jacob’s arrival, it is evident that the pharaoh of Joseph reigned a minimum of 11 years (and probably longer).

If our criteria for the pharaoh of Joseph are: 1) native Egyptian, 2) early 17th century b.c.e. and 3) reigned at least 11 years, then only Merneferre Ay fits the bill. According to Professor Ryholt’s The Political Situation in Egypt During the Second Intermediate Period, Merneferre Ay reigned for exactly “23 years, 8 months and 18 days,” putting him on the scene from 1701–1677 b.c.e. (Other slightly variant schemes include Egyptologist Thomas Schneider’s dating of his reign to 1684–1661 b.c.e.) This fits well with the arrival of Jacob’s family in Egypt during this period.

Merneferre Ay is well attested, with no fewer than 62 scarab seals and one cylinder seal. Fifty-one of these are of unknown provenance, and most of the rest are from Upper Egypt, but one seal from Bubastis and two from Heliopolis show that he continued to exert control in the Nile Delta region, despite the presence of the Lesser Hyksos.

Merneferre Ay is notable as the last Egyptian king of the 13th Dynasty to be attested to by objects from outside Upper Egypt. This has led Daphna Ben-Tor and many other Egyptologists to believe that the Lesser Hyksos drove the 13th Dynasty from the Delta during or just after Merneferre Ay’s reign.

Yet Professor Ryholt believes something else was a more likely cause, prompting this native Egyptian retreat from the Nile Delta: severe drought.

Conquering the Delta

Most literary analysis of the Joseph story revolves around the family drama between Joseph and his antagonistic brothers. But there is a fascinating event that puts the family drama into its historical context.

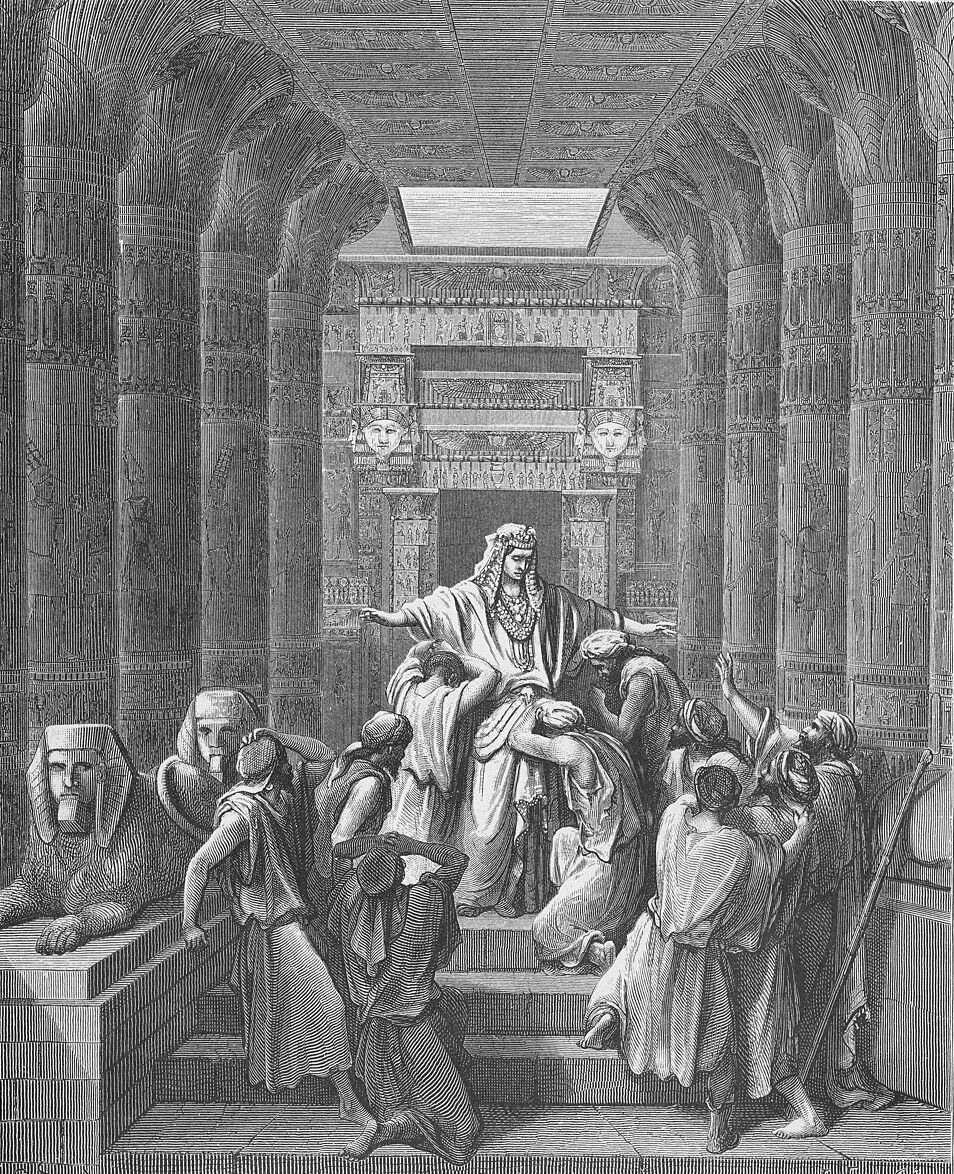

Joseph, interpreting the pharaoh’s dream, informed him that seven years of plenty would be followed by seven years of famine. He therefore recommended the pharaoh save 20 percent of Egypt’s grain harvest during the years of plenty in order to have stores during the years of want. As the account describes, the pharaoh, impressed with this counsel, made Joseph his second-in-command, giving him authority to carry out this project. Genesis 47 relays that Joseph sold this grain back to the Egyptians during the famine. At first the Egyptians paid with money, until their money ran out. They then paid with cattle, and finally, when that too had run out, they paid with the land they owned.

“So Joseph bought all the land of Egypt for Pharaoh; for the Egyptians sold every man his field, because the famine was sore upon them; and the land became Pharaoh’s. And as for the people, he removed them city by city, from one end of the border of Egypt even to the other end thereof. Only the land of the priests bought he not, for the priests had a portion from Pharaoh, and did eat their portion which Pharaoh gave them …” (Genesis 47:20-22).

This passage tells us that every landowner in Egypt, except the priests, sold their land to pharaoh. The Bible further tells us pharaoh put his own personal herds of cattle in the Nile Delta, setting Joseph’s family and workmen over them as “rulers over my cattle” (Genesis 47; again, in light of the native Egyptians despising herding).

This incident may solve an age-old mystery in the field of Egyptology. The testimony of ancient Egyptian historians, like the third-century b.c.e. Manetho, record that the Lesser Hyksos were conquered by another Semitic-speaking dynasty called Greater Hyksos, but archaeologists have never discovered any evidence of a violent conquest. Genesis 47, for its part, relates that Jacob’s family gained control over the Nile Delta territory peacefully. In aligning events with the biblical account, it can be inferred that the famine forced the Lesser Hyksos rulers to sell their land back to Merneferre Ay, who in turn established the Israelites as rulers over his cattle and land in the normally fertile Delta region.

Genesis 42:6 further tells us that pharaoh made Joseph “governor over the land.” The Hebrew word translated “governor” is salit—an unusual biblical term for a governor. Interestingly, Manetho records that the first ruler of the Greater Hyksos was an individual called Salitis (with the typical Ptolemaic Greek -is ending). It appears that the Lesser Hyksos sold their land to Merneferre Ay, who appointed Joseph as salit over the Delta. With “Salitis”—Joseph—entrusted as ruler overseeing northern Lower Egypt, Merneferre Ay would have been free to move his capital to Thebes, in the heart of native Egypt, while the Israelites took up residence at the Hyksos capital, Avaris.

No seal impressions of this first Greater Hyksos ruler, “Salitis,” have thus far been discovered. But in light of the biblical account, this should be unsurprising because Salitis was, strictly speaking, a governor—and one, at that, using his pharaoh’s ring as his authority: “And Pharaoh took off his signet ring from his hand, and put it upon Joseph’s hand …” (Genesis 41:42).

A Moment of Peace

With Joseph in the role of governor, his actions would have briefly reunited Egypt during a time of great calamity. This was not a status quo that would continue, however—ties would eventually become strained and ultimately severed between successors to both the native Egyptian pharaohs in Upper Egypt and Semites in Lower Egypt, leading to a situation where a new Theban pharaoh “knew not Joseph,” warning against the people to the north as being “too many and too mighty” (Exodus 1:8-9).

The pharaoh was not exaggerating. By the mid-16th century b.c.e., the Greater Hyksos of Avaris had indeed surpassed the strength of the native Egyptians. Tensions reached breaking point, with conflict eventually breaking out between the successors of Joseph and the successor of Merneferre Ay—a war in which, ultimately, the Egyptians prevailed and the Hebrews were enslaved.

Yet during Joseph’s lifetime, one can imagine a rare moment of great peace in the two lands of Egypt, with the Lesser Hyksos grateful that Joseph had saved their lives (Genesis 47:25), the native Egyptians grateful for regaining greater control over the Nile Delta, and the Israelites grateful for a new home.

The pharaoh—or, might we say, Merneferre Ay?—put it best: “And Pharaoh said unto his servants: ‘Can we find such a one as this, a man in whom the spirit of God is?’ And Pharaoh said unto Joseph: ‘Forasmuch as God hath shown thee all this, there is none so discreet and wise as thou. Thou shalt be over my house, and according unto thy word shall all my people be ruled; only in the throne will I be greater than thou’” (Genesis 41:38-40).

Further Reading:

The Hyksos: Evidence of Jacob’s Family in Egypt?

Who Was the Pharaoh of the Exodus?

Sidebar: The Famine Stele

The Famine Stele is a mammoth boulder inscription found on Sehel Island in the Nile River. It contains a story of a famine and drought, set during the reign of Pharaoh Djoser, lasting “a period of seven years. Grain was scant, kernels were dried up, scarce was every kind of food.” Naturally, it has been wondered if this describes the same event as the seven-year famine of Joseph. Yet Djoser’s reign is dated to many centuries before Joseph (within the third millennium b.c.e.), and this story contains alternate details, centering primarily around the Nile god Khnum.

But does that mean there is no possible connection of the inscription to events of the Joseph account? Not at all. That’s because the inscription dates not to the original Old Kingdom Period of Djoser but to the Ptolemaic period—as late as the third or second century b.c.e., produced by (or for) the Ptolemaic Khnum-priests.

The Famine Stele is part of a corpus of inscriptions Prof. Christopher Rollston identifies as “ancient forgeries,” composed with the pretense of a text far more ancient. Therefore, as a much later-period inscription at least purporting to relay events sometime deep in Egypt’s past, it could have drawn from an already established tradition of a seven-year famine event in Egypt’s history—perhaps none other than the famine of Joseph.