There’s a trend in the world of popular archaeology journalism. It’s one that seeks to highlight archaeological efforts in Jerusalem as a desperate “Zionist” attempt to “prove” their ancient roots in the city and claim it as their own—amid a backdrop of oppressed and blindsided Palestinian communities living in East Jerusalem. The archaeological work of the late Dr. Eilat Mazar is sometimes brought up as the example of a “diehard Zionist” zealot excavating Jerusalem in politically or religiously motivated excavations.

This dangerously divisive narrative, promulgated by armchair journalists, could not be further from the truth.

And it’s particularly grating because instead of dividing communities, archaeology efforts—particularly those of Dr. Eilat Mazar and her famous grandfather, Prof. Benjamin Mazar—should serve to unite them. Their excavations have, in large part, served to highlight Islamic history and scriptural accounts.

Islamic Era Remains

Prof. Benjamin Mazar could be considered one of the “founding fathers” of Israeli archaeology. His most significant excavation project, the Temple Mount excavations, took place in the territory abutting the outer southern and southwestern walls of the Temple Mount. These 1968-78 excavations constituted, to that point, the largest archaeology project ever in Israel, conducted in joint partnership between the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and our own forerunner institution, Ambassador College.

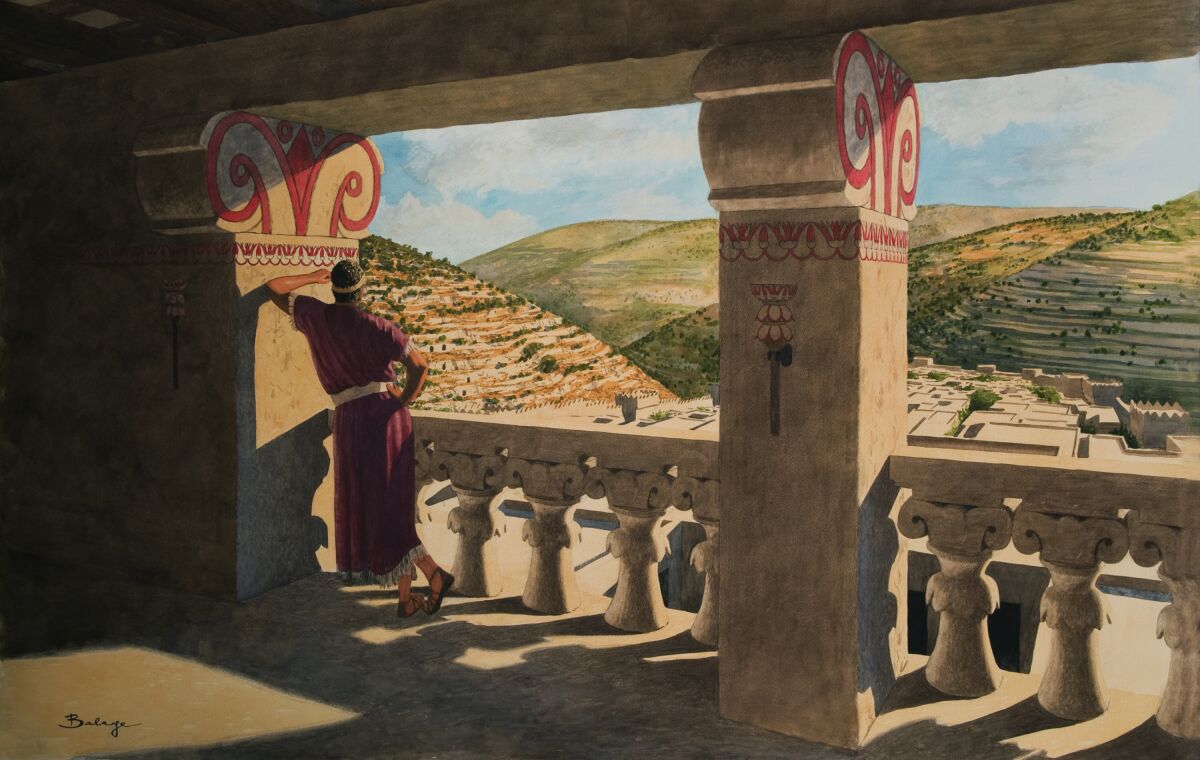

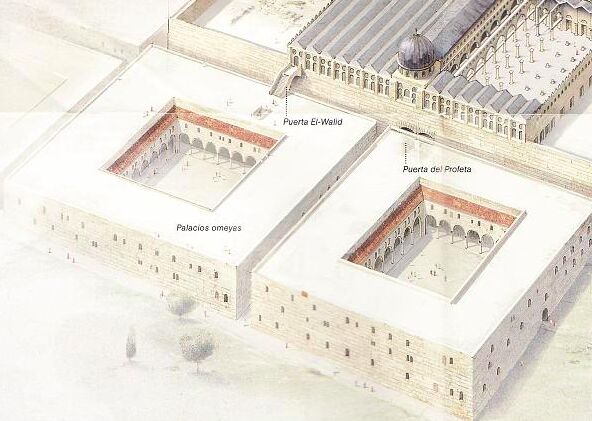

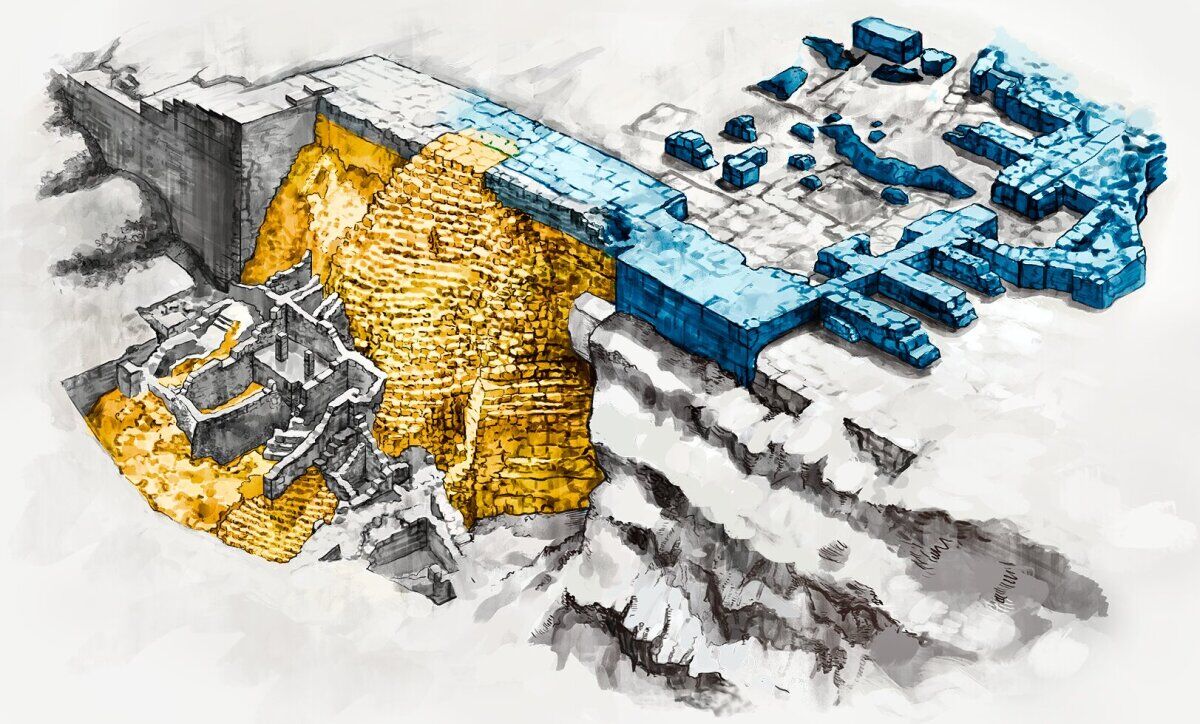

A prominence of remains discovered during those excavations were from the Islamic period. These remains can be seen and toured to this day—buildings and remains from the Umayyad, Ayyubid, Abbasid and Fatimid periods, including remains of the massive quadruple-squared-structure Umayyad Palaces, apparently constructed during the reign of caliph El-Walid (705–715 c.e.). The largest of the four palace squares measures nearly 100 meters x 100 meters.

Such discoveries were proudly displayed to visiting Muslim dignitaries by Professor Mazar, who made a name for himself for these tours.

And his efforts were carried on by his granddaughter Dr. Eilat Mazar.

I had the privilege of working for Dr. Mazar over the past several years, serving as a supervisor on her excavations and assisting her in office work. She was certainly nothing of the Jewish “zealot” that she is sometimes made out to be by her (often jealous) detractors. (And as an aside, she was not religious.) Her digs were staffed by Jews, Christians and Muslims alike, and she enjoyed practicing her Arabic with fellow Palestinian workers—both on the dig site and at Hebrew University.

In her latest 2018 excavation on the Ophel, in the same area in which her grandfather’s excavations took place (and her final one before she died), I remember one of the things she was particularly excited about was the rare discovery of very early Islamic period pottery. Pottery fragments, of course, are the mainstay of archaeology, and typology is critical to establishing chronologies. Dr. Mazar, who specialized in pottery reading, was intrigued to find the very earliest forms of Islamic pottery as they diverged and developed in form out of and away from the prior Byzantine forms. All such finds—pottery, weights, coins, structures etc of various Islamic periods—were given ample and full analyses in the Mazars’ scholarly and popular publications. And their personal libraries (which our institute has now been fortunate enough to gain possession of) are replete with volumes on Islamic history and religion (even in Arabic!).

Of course, what Dr. Mazar was most known for was her discoveries relating to the biblical kings of Judah—particularly David and Solomon. It is these that won her the most acclaim around the world—but also the most criticism.

David and Solomon

Dr. Mazar’s detractors (some of whom have built careers on theories undermining the historicity of David and Solomon) have brought up all kinds of reasons to question her discoveries—particularly that of “David’s Palace” (the Large Stone Structure) at the summit of the City of David, and “Solomon’s Royal Complex” (the Water Gate, Large Tower and related walls). Various accusations include the agenda of those funding the excavations (to which Mazar replied, “The stones don’t care who is giving the funds”) to political or Zionist motives aimed at strengthening the Jewish connection to Jerusalem, at the expense of the Palestinians.

Such arguments, however, detract from the science-based conclusions made during excavations. In short, Dr. Mazar made her associations based on the 10th-century b.c.e. construction of such structures—a date that fits directly with the chronology of kings David and Solomon—and such structures of a type and geographic location that directly fit specific details given in various biblical scriptures. (For more on this subject, read our article “Is It Really King David’s Palace?”)

But this subject should hardly be painted as a point of contention between Jews and Muslims. Because such discoveries only affirm what is also attested in the Qur’an.

Kings David and Solomon are mentioned by name nearly 20 times each throughout the Qur’an and are spoken highly of. The strength of David’s kingdom is mentioned (Surah 38:17-20), along with a possible incident that happened in David’s palace (:21-22)—a place mentioned as being ascended to. This is notable, because a key clue in Dr. Mazar’s identification of the palace location is linked to the biblical account of it being in a specific lofty place, that David descended from (i.e., 2 Samuel 5:17).

Also in the Qur’an’s account, King Solomon is described as a builder-monarch (Surah 34:12-13), likewise fitting with the biblical account of the king, as well as the 10th century b.c.e. northward expansion of Jerusalem discovered by Dr. Mazar.

These discoveries are hardly divisive—rather, divisiveness is only stoked by outlets such as CBS’s 60 Minutes that seek to make such discoveries relating to King David a partisan issue. Do they not know what the Qur’an says about David and Solomon? Have they not read the publication guide made by the Supreme Muslim Counsel in 1925 for the Haram al-Sharif/Temple Mount? It reads in part as follows (emphasis added):

The site is one of the oldest in the world. Its sanctity dates from the earliest (perhaps from prehistoric) times. Its identity with the site of Solomon’s temple is beyond dispute.

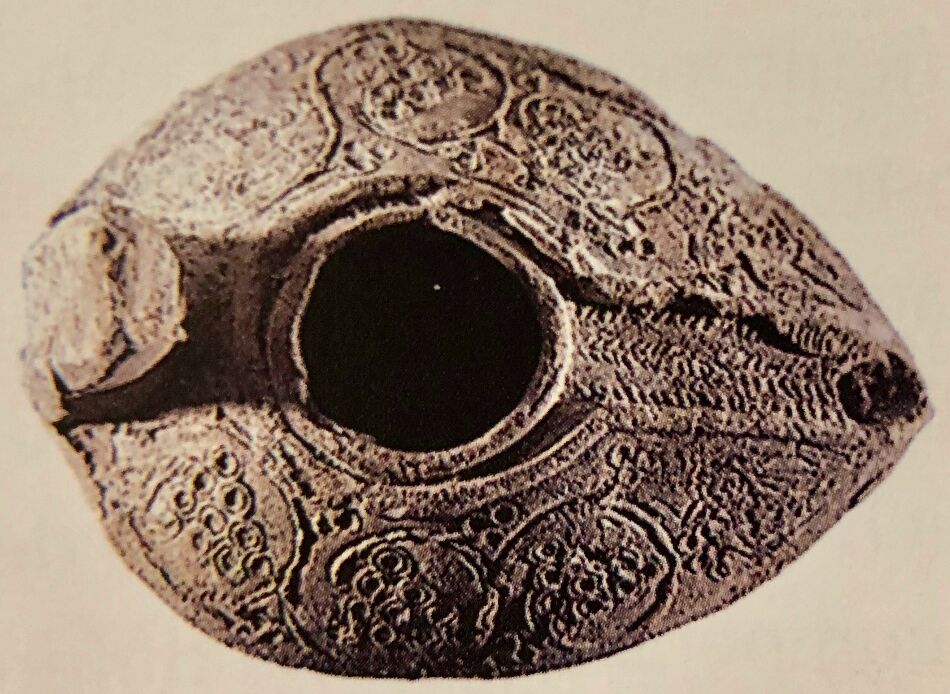

But it doesn’t just stop with David and Solomon: The remarkable discoveries of Eilat Mazar go further. What she considered her single-greatest find was discovered on the Ophel in 2009: The “Hezekiah bulla” is the first and only seal stamp impression of a king of Israel or Judah discovered on a controlled, scientific excavation. The seal stamp, which includes various motifs, reads: “Belonging to Hezekiah, [son of] Ahaz, King of Judah.” Not far from this bulla, within the same strata of soil, Dr. Mazar’s sifting team uncovered another parallel seventh-century b.c.e. bulla with the inscription “Belonging to Isaiah […] Nby[?].” While the seal was partially damaged, the three initial preserved Hebrew letters nby fit with the four-letter word “prophet,” nby’ (a virtually identical word in Arabic). The Hebrew Bible describes Hezekiah and Isaiah as being on the scene at this time, in this very area.

And they are also mentioned in Islamic literature. While the Prophet Isaiah is not mentioned in the Qur’an, he is mentioned in several other prominent and early Islamic sources. The same is true of King Hezekiah. Several details of events surrounding these men parallel those found in the biblical account, as well as in later Jewish traditional accounts.

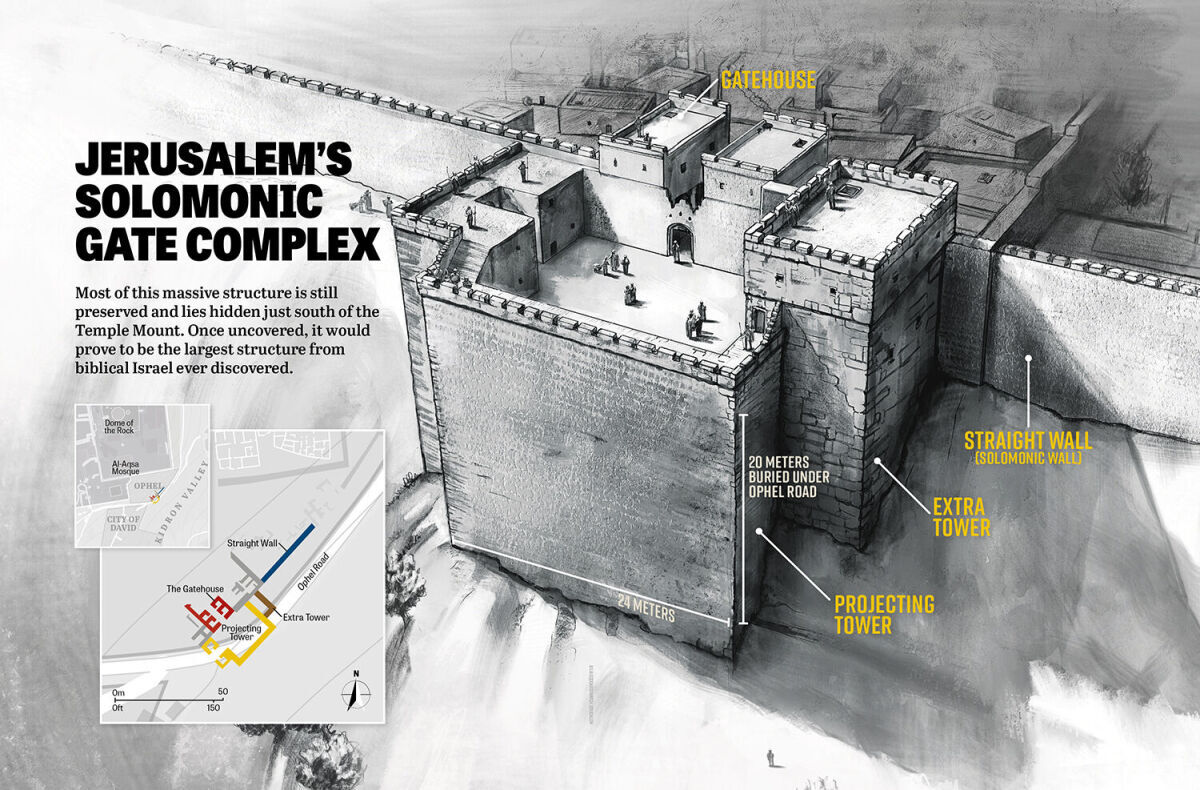

The remarkable discoveries of Dr. Mazar, some of which certainly still remain a hotbed for academic division (particularly about the place of Scripture in archaeological research), should not be a matter of religious or political division. These are sites that can be visited by Jews, Christians and Muslims alike, where they can see the large and prominent palace in which the King David of their scriptures dwelled; the ensuing, northward extension of Solomon’s Jerusalem toward the Temple Mount, including hundreds of meters’ worth of walls and a gatehouse; the royal quarter in which the royal seals of Hezekiah and Isaiah were discovered.

Tourists can see impressive remains from the rule of the Jewish kings, circa 10th–6th centuries b.c.e., followed by the transition to Persian control in the sixth–fourth centuries b.c.e.; they can see the setting for the New Testament among the Herodian remains of the first century c.e.; various buildings and discoveries can be seen through ensuing Christian and Islamic periods across the later first and second millenniums c.e.

One of the great shames of the past two years of the pandemic has been the small numbers of tourists among these mighty remains. Pandemic aside, this has unfortunately been the status quo for the Palestinian, wider Arab and Muslim communities in general. It’s a shame that more about these remarkable sites isn’t widely shared, understood and used to unite, particularly by the media. A precious historical and scriptural connection to these sites, as highlighted particularly by the work of Prof. Benjamin Mazar and Dr. Eilat Mazar; a connection that can be seen and felt, back to David and Solomon and even earlier, to the shared patriarch of Judaism, Christianity and Islam—Abraham.