Roughly five dozen personalities of the Hebrew Bible have been proved through archaeology, with many more “nearlies.” Perhaps unsurprisingly, none of the “proven” figures are women (given that 1,426 men are named in the Scriptures, compared to 111 women). The woman that probably comes closest to “proven” status is the infamous Jezebel.

Then there is “Bithiah, daughter of Pharaoh.”

You’d be forgiven if you’ve never heard of her. She is a peculiar woman with a single mention by name, buried in the chronologies of the book of Chronicles. Who is this princess? And is it possible to identify her with a known princess of Egypt?

The Chronicles Genealogies

The first nine chapters of the first book of Chronicles are a series of detailed genealogies relating to the tribes of Israel, the house of David in particular. This book is credited to the scribe Ezra (of the biblical book of the same name), who, with Nehemiah, participated in a genealogical review of the Jewish populace at the time of the return from captivity, notably determining who was applicable for priestly duty (Nehemiah 7).

The translation of the genealogical record in 1 Chronicles 4 has led to some debate and confusion, however. It appears this chapter, in the overall flow, is a piecemeal genealogical “cleanup” of remaining clans in the geographic southern area of Judah and Simeon. This chapter also lists several notable women—one of which is Bithiah.

“… Heber the father of Soco, and Jekuthiel the father of Zanoah—these are the sons of Bithiah the daughter of Pharaoh whom Mered took” (verse 18).

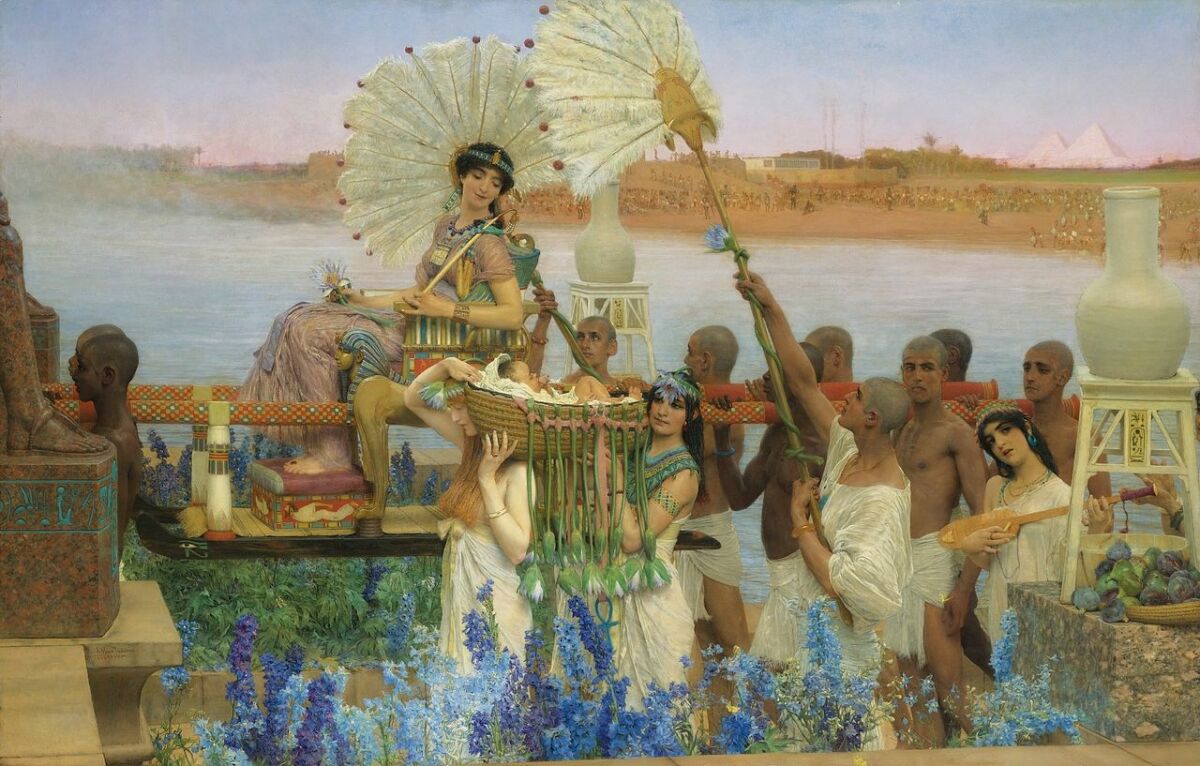

Placing an exact time frame for these individuals is difficult given the wording in this part of the genealogies. However, it has long been linked, according to Jewish tradition, with the period just before the Exodus—the time of Moses or just prior (with some speculating that this Egyptian princess was the one who rescued Moses). As we covered in a recent article, with an Exodus date around 1447–1446 b.c.e., that would best relate to sometime around the end of the 1500s b.c.e.

This time period makes sense given the names that appear here: Verse 17 mentions a Miriam (a well-known name from the Exodus period); there was evidently some kind of close Israelite contact with Egypt at this time, as verse 18 shows; yet it appears this was also a time of growing upheaval, likewise fitting just prior to the Exodus, as indicated by certain of the names (for example, Mered means “rebellion”). Further attesting to the early genealogy of this passage are the names of fathers of what would later become Israelite cities in the Promised Land (e.g. Socoh, Gedor and Zanoah).

Given all of this—is it possible to locate an Egyptian princess around the 1500s b.c.e. who could parallel Bithiah?

Beautiful Bity

Pharaoh Hatshepsut (circa 1507–1458 b.c.e.) is one of the most famous female rulers of human history (we have mentioned in a previous article how she may specifically relate to the Exodus story). She was the daughter of the prior Pharaoh Thutmose i and his Great Royal Wife Ahmose.

But there was another daughter born to Thutmose i and Ahmose, a sister of Hatshepsut—one who inexplicably disappeared.

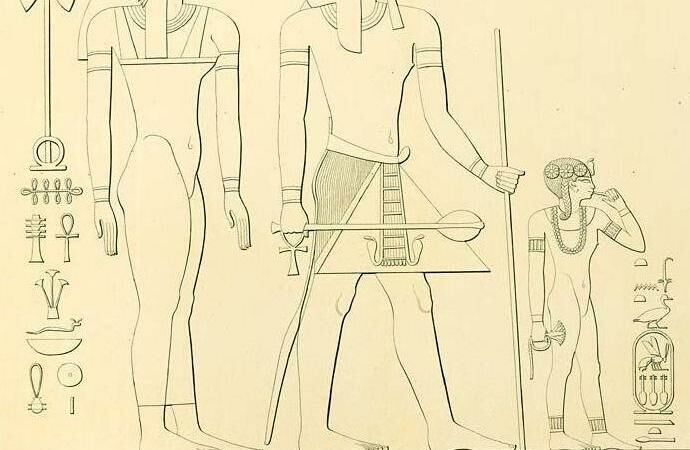

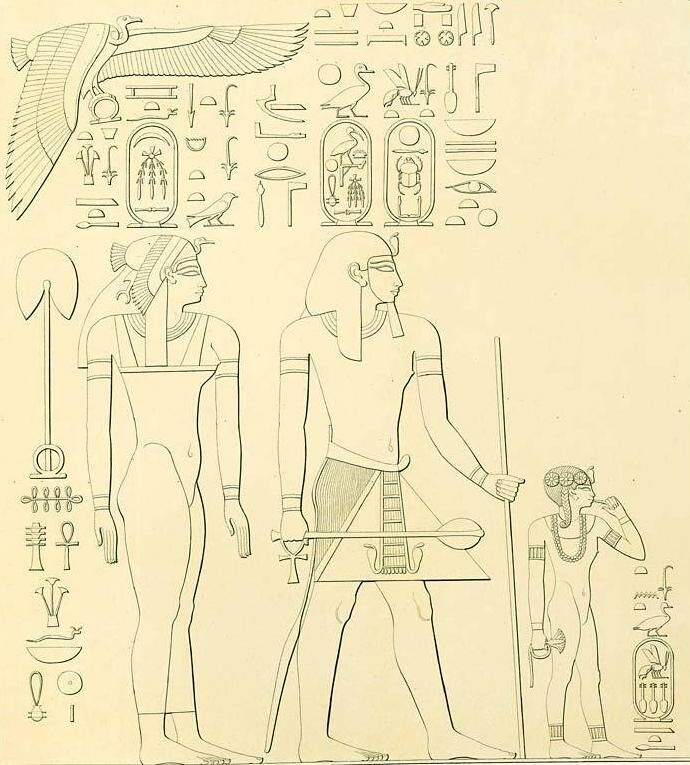

Among the detailed reliefs at the Deir el-Bahari temple in Luxor, Egypt, is an image of Queen Ahmose, Pharaoh Thutmose i and a well-decorated young daughter named Nefrubity. This image and surrounding hieroglyphic text is all that is known of Nefrubity; after this, she completely disappears from the record. A typical assumption is that she died young.

Her name, Nefrubity, is interesting, consisting of two parts—Nefru and Bity. Nefru/nfr is a common name element meaning beauty, or beautiful (and Bity can be translated as “bee”). Her sister Hatshepsut’s own daughter was named Neferure, “beauty of [the god] Re.” Her father Thutmose i’s other wife’s name, Mutneferet, means “[the goddess] Mut is beautiful.” On the extreme end of the spectrum, there is the famous 14th-century b.c.e. Queen Nefertiti—or, in full, Neferneferuaten Nefertiti (“beautiful are the beauties of [the god] Aten, a beautiful woman has come”).

Could Nefrubity, then—“beautiful Bity”—be a name match for our Bithiah of the Bible (a name properly pronounced in Hebrew, Bitya)?

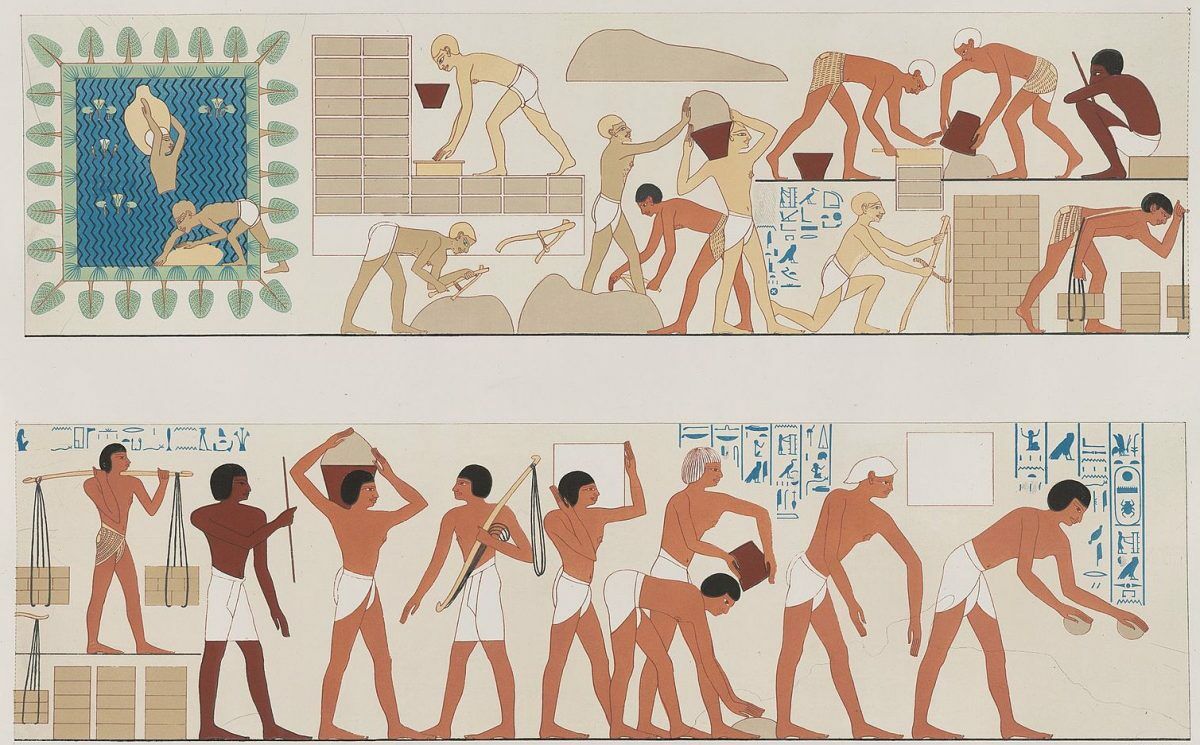

The name, dating, even her inexplicable disappearance from Egyptian records would be a potential fit for the biblical account. After all, this was a time following great upheaval in Egypt against the Hyksos, the enigmatic reigning Semitic rulers located in the north of Egypt (Lower Egypt), whom Thutmose i’s father had chiefly worked to overthrow during the 16th century b.c.e. It’s noteworthy that the first-century historian Josephus directly equated these Hyksos, whose Egyptian name he translated as “shepherd kings,” as the Israelites living and ruling in the northern land of Egypt. (Further, the hieroglyph for Bity is itself a symbol for Lower Egypt, the place inhabited by the Israelites—the part of Egypt including the “Land of Goshen.”) Continuing forward into the 15th century, there is evidence of Semite slaves being oppressed and forced into back-breaking, brick-making labor.

Could it be possible that Nefrubity, daughter of the pharaoh, disappeared as the one “whom Mered [‘rebellion’] took” for his wife following the period of uprising against and driving out the Hyksos—the unfortunate time when “there arose a new king over Egypt, who knew not Joseph”? (Exodus 1:8).

The Israelite sojourn in Egypt is a fascinating biblical setting—and one for which there are a surprising number of archaeological parallels, right down to parallel period names such as Jacob, Shiphrah (the Israelite midwife) and the especially notable “Moses” name element of this specific Exodus period (note Thutmose/Thutmosis, Ahmose, Wadjmose and Amenmose, etc). Is “beautiful Bity” another name that could be added? For now, we can only speculate, but it is interesting to do so nonetheless. For more about this Exodus and Egyptian sojourn period and the archaeological evidence behind it, read our article “Evidence of the Exodus?”