Solomon’s temple (the first temple) and Herod’s temple (the rebuilt, second temple) were two of the finest constructions of the ancient world, and the pride of those that worshiped there. Today, however, as a result of numerous invasions and conquests over thousands of years, almost no definitive artifacts or architecture of the inner temple complex remains. Jerusalem, after all, has been one of the most repeatedly besieged places on Earth.

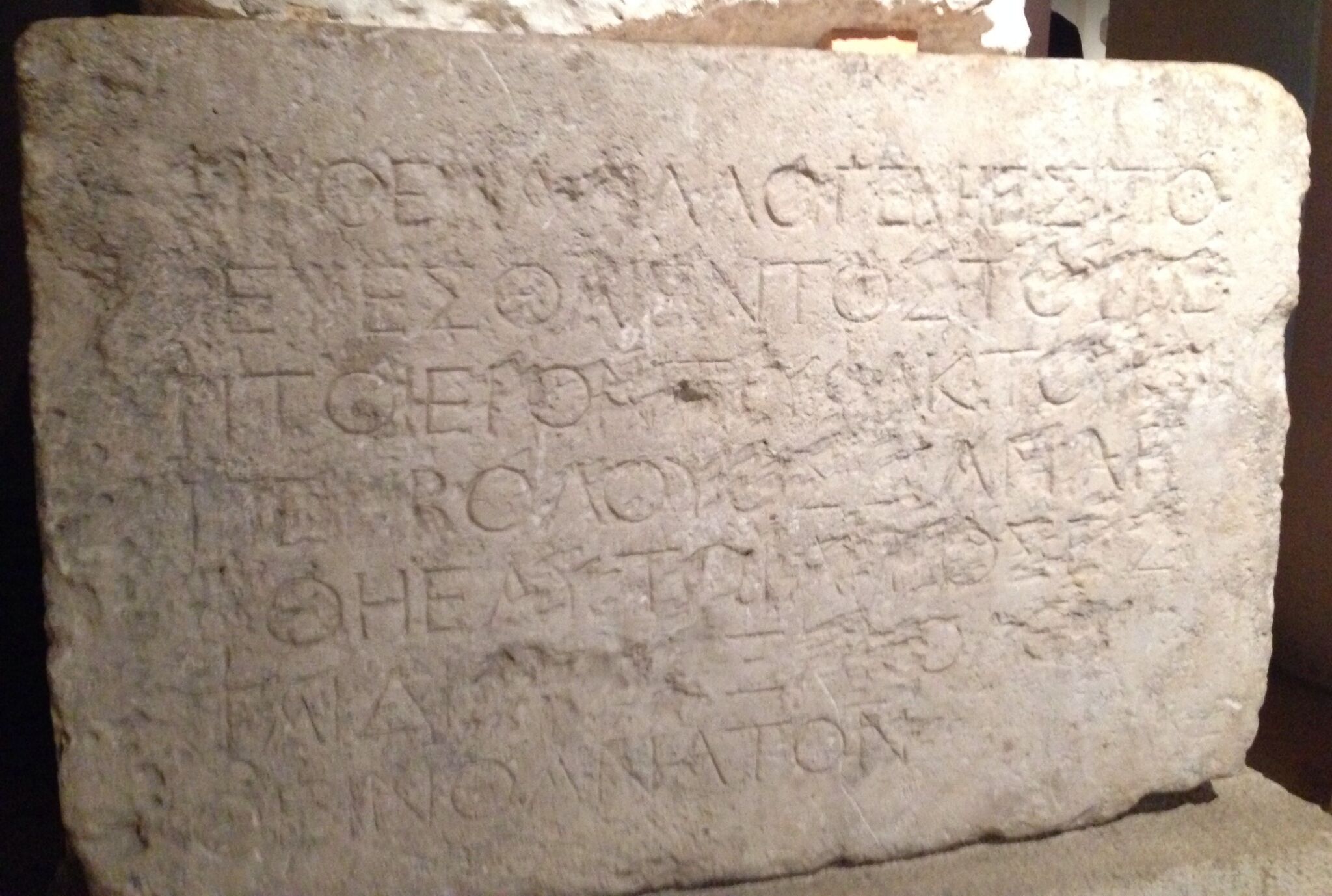

No definitive artifacts, that is, besides two remarkable stone inscriptions from Herod’s temple. According to David Mevorach, senior curator at the Israel Museum, these stones are the “closest thing to the temple we have.”

They are known as the “Temple Warning Inscriptions.”

These inscriptions are particularly special because they were well documented by eyewitnesses to the temple in classical antiquity. The first-century c.e. Jewish historian Josephus described an inner courtyard stone border wall, containing inscription ashlars “at equal distances from one another, declaring the law of purity, some in Greek, and some in [Latin] letters, that ‘no foreigner should go within that sanctuary’” (War of the Jews, 5.5.2). He further mentioned this warning in his book Antiquities of the Jews: “an inscription, which forbade any foreigner to go in under pain of death” (15.11.5). This low stone border wall separated the “holy” court from the “unholy.”

The first-century philosopher Philo also wrote of this prohibition (Leg. 212). In the New Testament, the Apostle Paul was accused of violating it (himself a Jew, but accused of bringing a Gentile with him), and he narrowly escaped death (Acts 21:26-32). The Mishnah, tractate Middoth, quotes eyewitnesses to the layout and measurements of the temple in the decades following its destruction. It has particulars about the “soreg” wall that contained these stones.

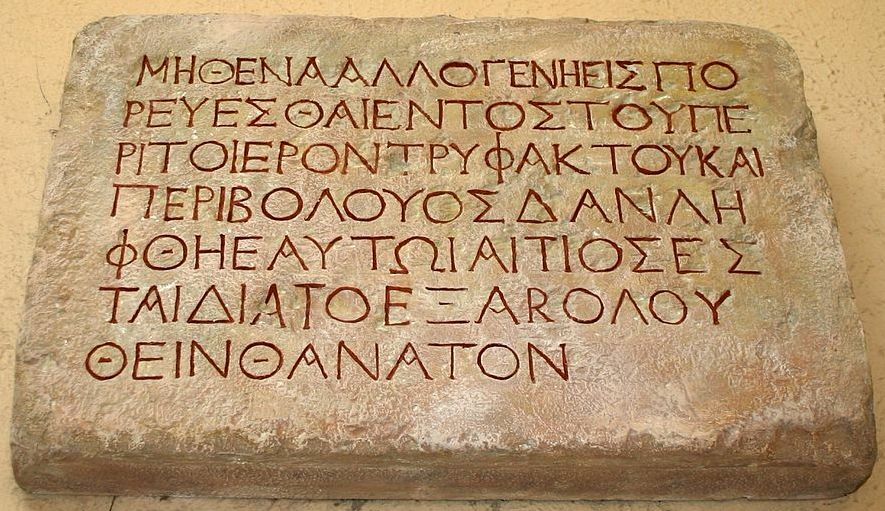

Exactly 150 years ago this year, those writings were dramatically brought to life. In 1871, the famous French archaeologist Charles Simon Clermont-Ganneau discovered a large ashlar stone bearing a slightly damaged Greek-language inscription. The stone was found in secondary use, having been repurposed for a building just outside the “Gate of Darkness” on the northern end of the Temple Mount. The seven-line Koine Greek inscription was as follows:

ΜΗΘΕΝΑΑΛΛΟΓΕΝΗΕΙΣΠΟ

ΡΕΥΕΣΘΑΙΕΝΤΟΣΤΟΥΠΕ

ΡΙΤΟΙΕΡΟΝΤΡΥΦΑΚΤΟΥΚΑΙ

ΠΕΡΙΒΟΛΟΥΟΣΔΑΝΛΗ

ΦΘΗΕΑΥΤΩΙΑΙΤΙΟΣΕΣ

ΤΑΙΔΙΑΤΟΕΞΑΚΟΛΟΥ

ΘΕΙΝΘΑΝΑΤΟΝ

Translated into English:

NO FOREIGNER IS TO GO BEYOND THE BALUSTRADE AND THE PLAZA OF THE TEMPLE ZONE. WHOEVER IS CAUGHT DOING SO WILL HAVE HIMSELF TO BLAME FOR HIS ENSUING DEATH.

The discovery was an exciting one: finally, a clear remnant of inner temple architecture. Unfortunately (for the later State of Israel), the Holy Land at that time was under the control of the Ottoman Empire, part of an area known as “Ottoman Syria.” As such, the Temple Warning Inscription was whisked away to Turkey (as with other important artifacts, such as the Siloam Inscription and an ill-fated Jeroboam seal), where it remains on display to this day.

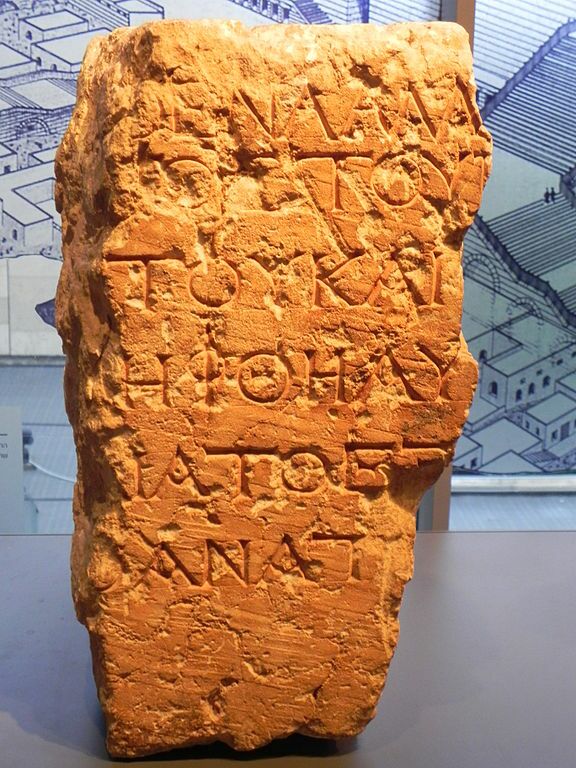

But all was not lost for the future Israeli State’s chance to have such a precious artifact. In 1935, another stone inscription was found. This one was much more fragmentary, but contained enough of the Greek inscription to note it as a match for the earlier discovery; it was another of the same “soreg” wall stones bearing precisely the same message. This item was found in secondary use in a tomb just outside the Lions’ Gate (northeast of the Temple Mount). It is currently on display in the Israel Museum in Jerusalem.

Traces of red paint remain inside the grooves of the letters, meaning that in their original state, they would have stood out in stark warning contrast as a “stop” sign (as shown in the image earlier in this article).

Other inscriptions and beautiful architectural fragments have been discovered relating to the general temple area; however, the exact original location and nature of these artifacts is unclear. The Temple Warning Inscriptions remain the “closest” confirmed, placeable, reconstructible, central “thing to the temple we have,” representing actual, tangible parts of Herod’s second temple complex. Prof. Jonathan Price of Tel Aviv University commented that “the level of destruction on the Temple Mount was so extensive that it’s lucky we even have those fragments.”

In a way, these inscriptions warning against entry to the temple carry a sad poetic irony, pointing to a temple that indeed can no longer be entered and the restricted status, albeit under rather reversed circumstances, that continues to this day.