Thoughts on Velikovskian Chronology—From One of Its Staunchest Former Proponents

Psychologists usually set out to study phenomena. Sometimes, however, they create them. Welcome to the Velikovsky Affair.

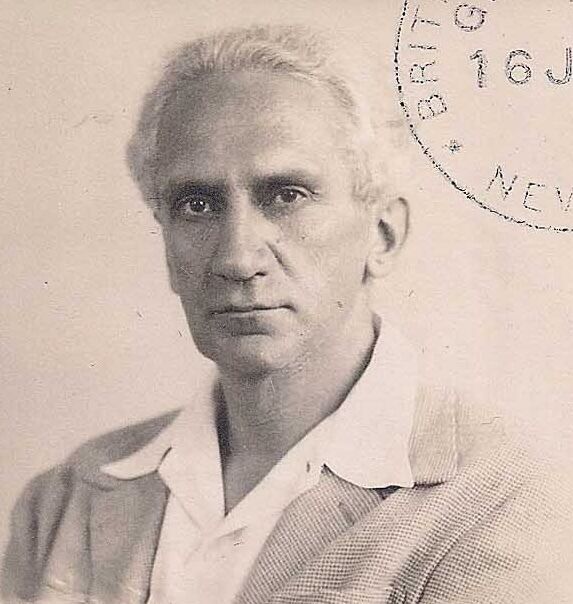

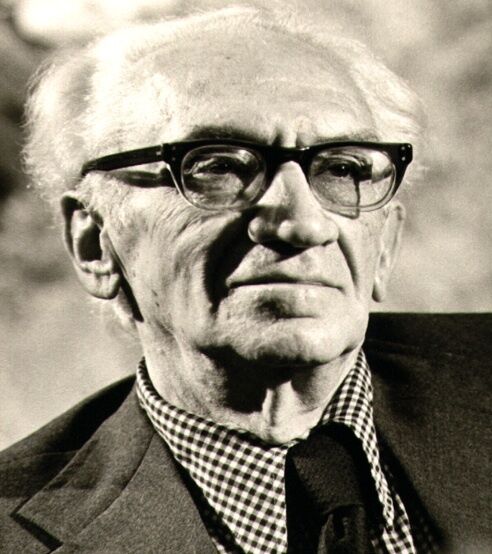

The late Russian-American psychoanalyst Dr. Immanuel Velikovsky (1895–1979) is famous for formulating an entirely novel chronology of history. Velikovsky developed his new and radical interpretation of history by piecing various myths and ancient texts from around the world together with the biblical account. His interpretation of history was also built around a peculiar model of interplanetary catastrophism; he believed that major events in Earth’s history were shaped by close encounters with wayward planets in our solar system.

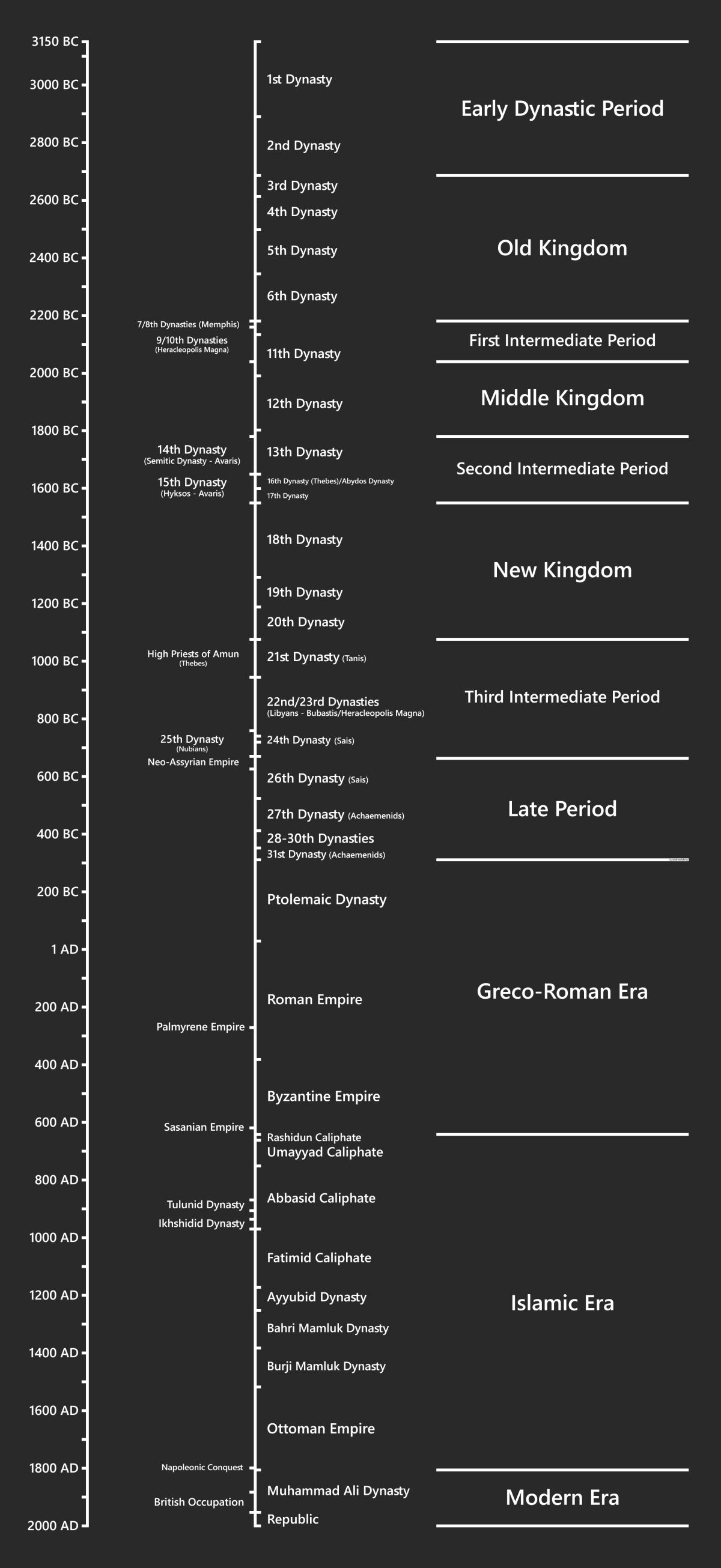

Velikovsky began publishing his new chronology of history in the 1940s, significantly down-dating much of ancient Egyptian history—pushing events and figures forward by as much as six centuries. For example, Velikovsky redated the female pharaoh Hatshepsut from the 16th-to-15th-century b.c.e. to the 10th century b.c.e., identifying her as the biblical Queen of Sheba (1 Kings 10). Similarly, he redated Thutmose iii (Hatshepsut’s successor) to the 10th century b.c.e. and identified him as the biblical Shishak (2 Chronicles 12). What about Sheshonq i, the 10th century b.c.e. pharaoh traditionally identified as Shishak? Velikovsky pushed him two centuries later, toward the end of the eighth century b.c.e.—identifying him as the biblical So (2 Kings 17). As for the famous 13th-century b.c.e. Ramesses ii? This pharaoh he redated to the seventh-to-sixth century b.c.e., identifying him as the biblical Necho (2 Chronicles 35).

Key to Velikovsky’s hypothesis was his “ghost double” concept. In many cases, he identified figures of different names in different texts—conventionally accepted to be different individuals—as “ghost doubles” of one and the same individual. The same he believed to be true for events in history. A key claim undergirding much of Velikovsky’s hypothesis, for example, was that the Battle of Kadesh between Egypt’s Ramesses ii and the Hittite king Muwatalli ii in 1274 b.c.e. was the “ghost double” of the 605 b.c.e. Battle of Carchemish between Egypt’s Necho ii and Babylonia’s Nebuchadnezzar ii. In this scheme, Ramesses ii and Necho ii are “ghost doubles,” as are Muwatalli ii and Nebuchadnezzar ii. (Note: In order to identify a Hittite and Babylonian king as the same historical figure, Velikovsky alleged the notion of a Hittite Empire to be but a modern invention, regarding it as synonymous with the centuries-later Neo-Babylonian Empire.)

Velikovsky’s view of history was novel and creative, with his publications enjoying a groundswell of public interest and support. The reaction of mainstream scholars and scientists, however, was the exact opposite; his radical new interpretations were fiercely opposed, rejected as unsubstantiated and unscientific. This difference between scholars and the general public in their view of Velikovsky has itself become a studied phenomenon, known colloquially as the “Velikovsky Affair.”

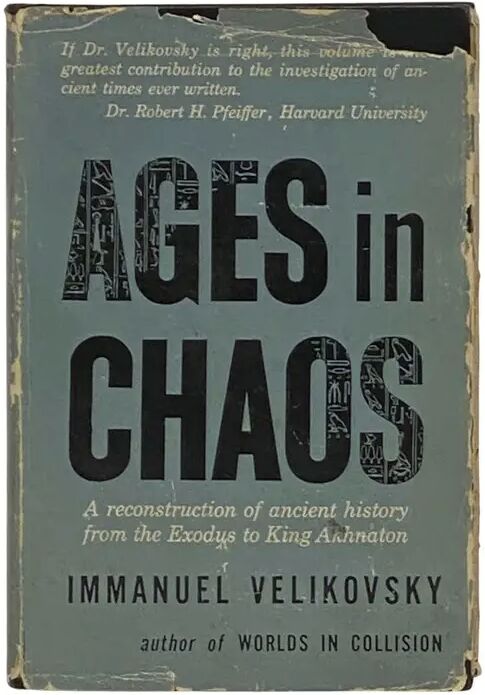

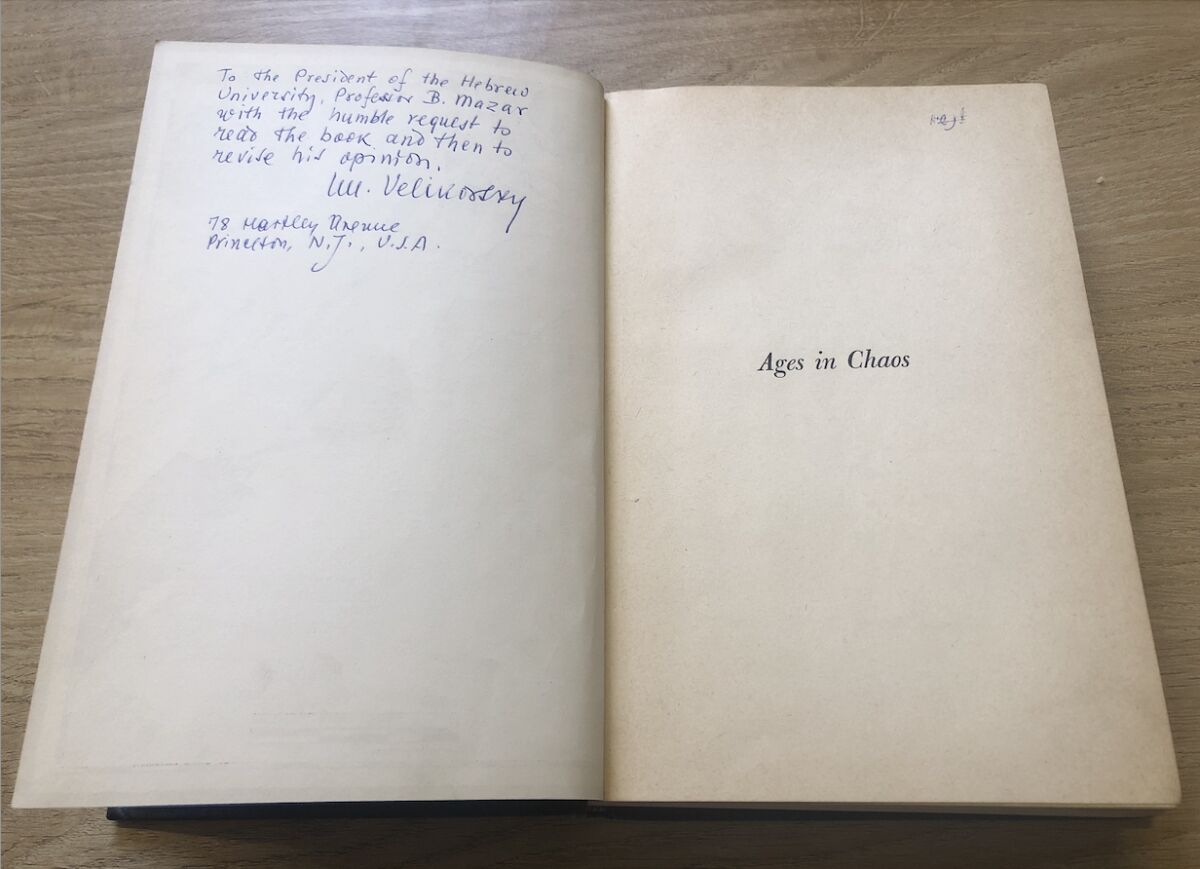

It is not rare for us at the Armstrong Institute of Biblical Archaeology to receive correspondence about Dr. Velikovsky and his view of history. Many have asked if I have read his material, notably Ages in Chaos. I have, and I do not subscribe to it. Those who read our material know that we generally follow the standard historical chronological system.

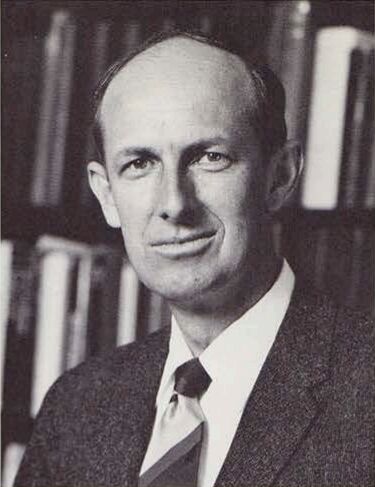

There are several reasons we do not follow the Velikovskian model, many of which can be found on other websites addressing this subject. In this article, however, we’ll approach this subject from a unique perspective—considering the example of the late historian Dr. Herman Hoeh, who was once an avid proponent of Velikovsky, but eventually made a dramatic 180-degree turn.

Compendium of World History

Dr. Herman Hoeh (1928–2004) was a student of our namesake, Herbert W. Armstrong, at Ambassador College—attending Ambassador the very first year it opened (1947). Dr. Hoeh had a deep interest in biblical history and archaeology, writing dozens of articles on the subjects, with his efforts culminating in his Compendium of World History. The first volume of this summation of world history was drafted in 1962, followed by a revised edition completed in 1967. That same year, his colleague Roy Schultz completed a publication following the same chronological outline, titled Exploring Ancient History: The First 2,500 Years.

Dr. Hoeh and Roy Schultz both drew heavily from Dr. Velikovsky’s interpretation of history—as is obvious in the chronologies presented in both the Compendium of World History and Exploring Ancient History.

But barely a decade following the completion of his Compendium of World History, Dr. Hoeh had dramatically changed his mind—in a 180-degree about-face, he rescinded his earlier framework and began dating figures and events following the standard historical model of chronology. Why the sudden and dramatic change?

In a 1977 Ambassador College address, Dr. Hoeh recounted his lifelong interest in history, identifying Velikovsky as his key source of inspiration. “[S]hortly after the founding of Ambassador College, Immanuel Velikovsky proposed a revolutionary model of Earth history,” he said. “It greatly relieved the pressure of history which seemed to compact the whole of geology since the Mesozoic in an unaccountably short time. I drafted Volume i of the Compendium on the basic proposals of Velikovsky.” In another address at Ambassador College later that year, he stated: “Immanuel Velikovsky … came out at a time when most historians outright were rejecting the Bible. The others were simply ignoring early Bible history. Velikovsky, on the other hand, was quite a student of the Bible.” Dr. Hoeh’s view of history was, by his own admission, heavily influenced by Immanuel Velikovsky.

New developments in the study of history, however, were increasingly exposing flaws in the Velikovskian model. Right from the outset of the publication of Velikovsky’s revised chronology, new technologies and new archaeological discoveries were increasingly being made, challenging his conclusions.

A case in point was the emergence of carbon dating (C-14 dating) at the end of the 1940s. Intriguingly, the initial data did conform to a degree more closely to Velikovsky’s much later dating for Egypt’s Old Kingdom period (third millennium b.c.e.). Yet this was not the case for the following historical periods, with C-14 data generally corroborating the standard historical model for these later periods (this trend continued as C-14 dating was refined over the decades). In his 1977 lecture, Dr. Hoeh noted that “Velikovsky is still laboring … trying to defeat C-14 evidence.”

In addition to the use of carbon dating, archaeological methodology in general was progressing and becoming more sophisticated. New discoveries were constantly being made, allowing a clearer, more detailed and accurate understanding of strata and different periods. The evidence increasingly revealed historical figures and events aligning more closely with the dates established using standard chronological models (with variants differing by years and decades). Those holding to Velikovskian chronologies (differing by multiple centuries) increasingly found themselves battling to reconcile discoveries with their differing timelines.

Cases in Point

The following are some cases in point, pertaining especially to Dr. Hoeh’s original model.

Standard chronology places the Assyrian king Shalmaneser iii on the scene during the mid-ninth century b.c.e., and a later Shalmaneser v on the scene toward the end of the eighth century b.c.e., initiating the siege against Samaria (a figure named in the biblical account—2 Kings 18:9). In his early works, Dr. Hoeh proposed that these two Shalmanesers were an example of the “ghost double” concept. He identified them as one and the same individual on the scene in the late eighth century b.c.e.—one and the same individual responsible for besieging Samaria.

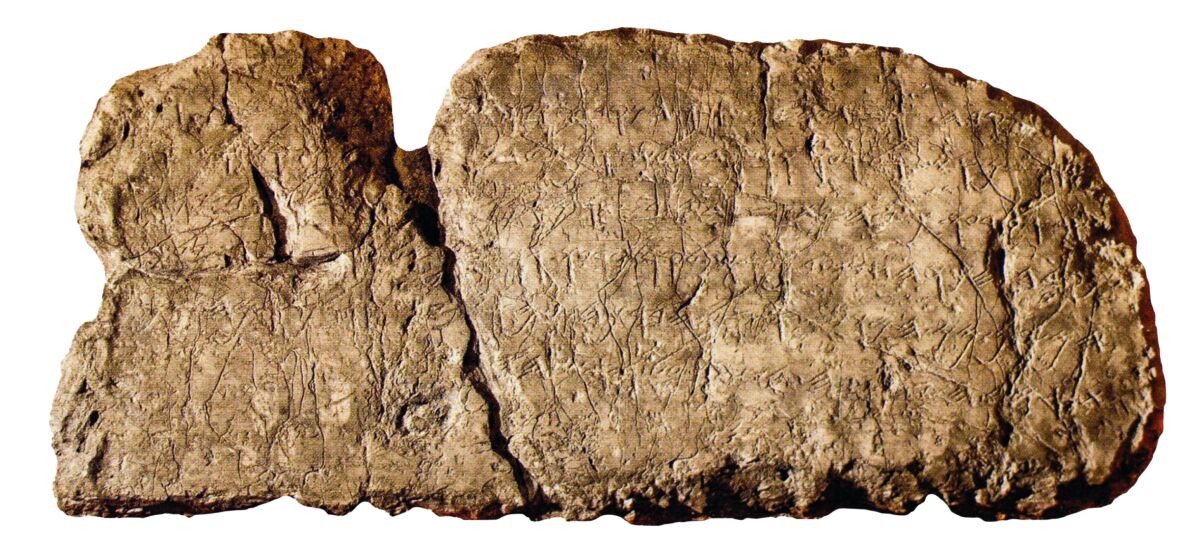

This conclusion, however, creates a number of problematic knock-on effects. For example, the inscriptions of Shalmaneser iii—namely, the Kurkh Monolith, Kurba’il Statue and Black Obelisk—make mention of his interactions with “Ahab the Israelite” and, later in his reign, “Jehu.” Both Ahab and Jehu were Israelite kings on the scene during the mid-ninth century b.c.e. (following biblical chronology), fitting with the standard placement of Shalmaneser iii. Yet identifying Shalmaneser iii as one and the same as the late eighth-century b.c.e. Shalmaneser v requires explaining what Ahab and Jehu are doing on the scene well over a century later.

In the Compendium, in order to fit these individuals into his chronological system, Dr. Hoeh reasoned that the “Ahab” mentioned on the Kurkh Monolith must have been an otherwise-unattested biblical king of Israel—an “Ahab ii”—positing him as reigning during a gap-period within the tenure of Israel’s final ruler, Hoshea (2 Kings 15:30; 17:1). As for Jehu, he likewise claimed him to be a biblically-unattested governor installed by the Assyrian king following the defeat of Samaria.

It is one thing to posit otherwise-unknown or little-known figures fitting within gaps of certain obscure periods. It is another to take two well-known royal names out of a period in which they do otherwise fit and reassign them to another period entirely, proposing them as entirely novel, otherwise-biblically-unnamed rulers. (Further, the mentions of Ahab and Jehu fit so particularly within the reign of Shalmaneser iii that they provide the key that unlocks the dating of other related kings and events—see here and here for more detail.) At best, this case in point belies the inherent problems with such a chronological model and the lengths required to make it fit.

Another case in point is the Amarna Letters. In their standard chronological context—the 14th century b.c.e.—these letters document, among other things, the havoc wrought by the Habiru people in the land of Canaan. (In other articles, we have discussed this topic in light of the ongoing conquest of Canaan by the Hebrews.) Yet following a Velikovskian scheme, these Amarna Letters are placed some five to six centuries later, well within the period of the Israelite and Judahite monarchies.

But here again, this presents irreconcilable difficulties. The content of these letters reveal the thoroughly fragmented Canaanite nature of the Levant, with its cities ruled by Canaanite governors from north to south—including Abdi-Heba, ruler of Jerusalem—subservient to the Egyptian pharaoh (all the while terrified of the progress of the Habiru in conquering “all the lands”). This does fit with the picture of the general traditional dating for the Amarna Letters, against the backdrop of a tribal and divided Canaan composed of individual city-states reporting to an Egyptian hegemon. It certainly does not fit with a period deep inside of the Judahite and Israelite monarchies.

Coming Full Circle

In his 1977 lecture, Dr. Hoeh went on to describe the progress of scientific research that made this original thesis untenable. “Something was clearly wrong with my understanding of history as laid out in Volume i of the Compendium of World History,” he said. “My reconstruction was wrong …. What we have now been forced to face is the fact that the broad outline of history for this period [the Bronze Age] is correct for the Middle East, except for the fact that the Bible has been deliberately left out of the account.”

“We are now also forced to reject Immanuel Velikovsky’s reconstruction of the Hyksos and empire periods of Egypt,” he said. The Hyksos period, traditionally dated to the early second millennium b.c.e., had been down-dated by Velikovsky to the late second millennium b.c.e. and reposited as a judges-period Amalekite occupation of Egypt. The following Egyptian empire/New Kingdom period, traditionally spanning the second half of the second millennium b.c.e., had been down-dated to the first half of the first millennium b.c.e., synchronous with the Israelite monarchy. Dr. Hoeh continued:

Evidence from the genealogy of priests at Memphis exists, which now makes it possible to accept the 18th Dynasty of the Tuthmoses as beginning parallel with Exodus 1:8, which is the approximate date normally assigned by historians. Their primary error was in leaving out the Bible record. So it is now possible to reconcile Bible, history and C-14 with a totally new view …. [I]f you read it for what it says and take what the historians have properly evaluated from the literature of the Egyptian period of the 18th Dynasty, we would draw the conclusion that indeed the 18th Dynasty of the Late Bronze and close of the Middle Bronze is the approximate period of the setting of the account of the Exodus.

These periods—the close of the Middle Bronze and Second Intermediate for the Israelite sojourn in Egypt, and the Late Bronze/18th Dynasty for the Exodus, including their remarkable relation to the biblical account—are highlighted elsewhere in detail on our website.

History Not Simply a Sliding Rule

It is vital to realize, for those attempting chronological revision (especially to any significant degree), that history and archaeology are not simply a sliding rule of names and numbers that can be moved back and forth and crossed over with abandon. Such historical individuals are directly connected to material on the ground—to associated archaeological strata—which cannot so easily be moved.

Dr. Hoeh explained the original methodology and the stratigraphical implications in a January 1978 conference lecture:

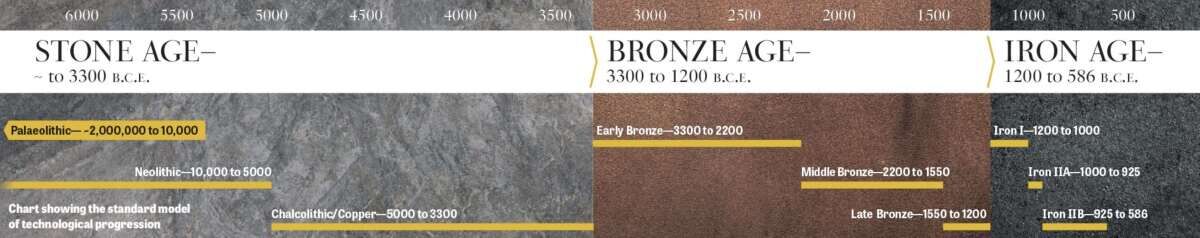

A solution seemed to have been found, as I mentioned, in Immanuel Velikovsky, who tended to drop history, beginning with the Exodus, some 500 years, which tended to make room—and of course we come to the problem of whether at the end of the reconstruction it was possible of assemble the material properly. … We placed the “Old” and the “Middle Kingdom” of Egypt as parallel, the “Intermediate” period of the Hyksos as the time of the judges, and the period of the great empire of Egypt paralleling the kings [of Israel]. And this required us to place the period of time that we call the “Iron Age,” normally associated with the kings of Israel and Judah, into the time of the Persian, Late Persian, Hellenistic and Early Roman.

Yet by the late 1960s and 1970s, Dr. Hoeh and Ambassador College had become partners in a number of archaeological initiatives. This changed everything: “As a result of our participation in archaeology and our relationship to some of the studies that have been going on over a decade, in 10 years we have tried to evaluate all of the fields that are interrelated.”

“[W]e have had to reevaluate also our thinking,” Dr. Hoeh stated. He proceeded to highlight a handful of examples:

Epigraphy is the study of texts, in terms of the style of script used. For instance, Hezekiah’s tunnel referred to in the Bible not only has been discovered but the inscriptions of the day defining how it was finally achieved has been known of course to the scholarly world. Unfortunately, the style of the script of the period of time of which we are dealing, the close of the eighth century b.c., we were forced archaeologically to place [in the original scheme] into the Hellenistic period. Similarly, the “Mesha Stele”—the stone of the king of Moab—records his revolt against Israel. That, of course, brings you into the lifetime of the immediate descendants of Moab, and has a particular kind of script which properly belongs to that generation. After all, it was written at that time. But we were forced to place its parallels in the early Hellenistic period. And this is because archaeology was forced down, and geology ….

In short, the text type of such famous inscriptions matches directly and precisely with those found in corresponding Iron Age layers. Yet if such Iron Age strata, and the inscriptions within them, are forced up to half a millennium forward in history, this forces these great biblical inscriptions forward in like manner—ripping them right out of their associated biblical periods entirely.

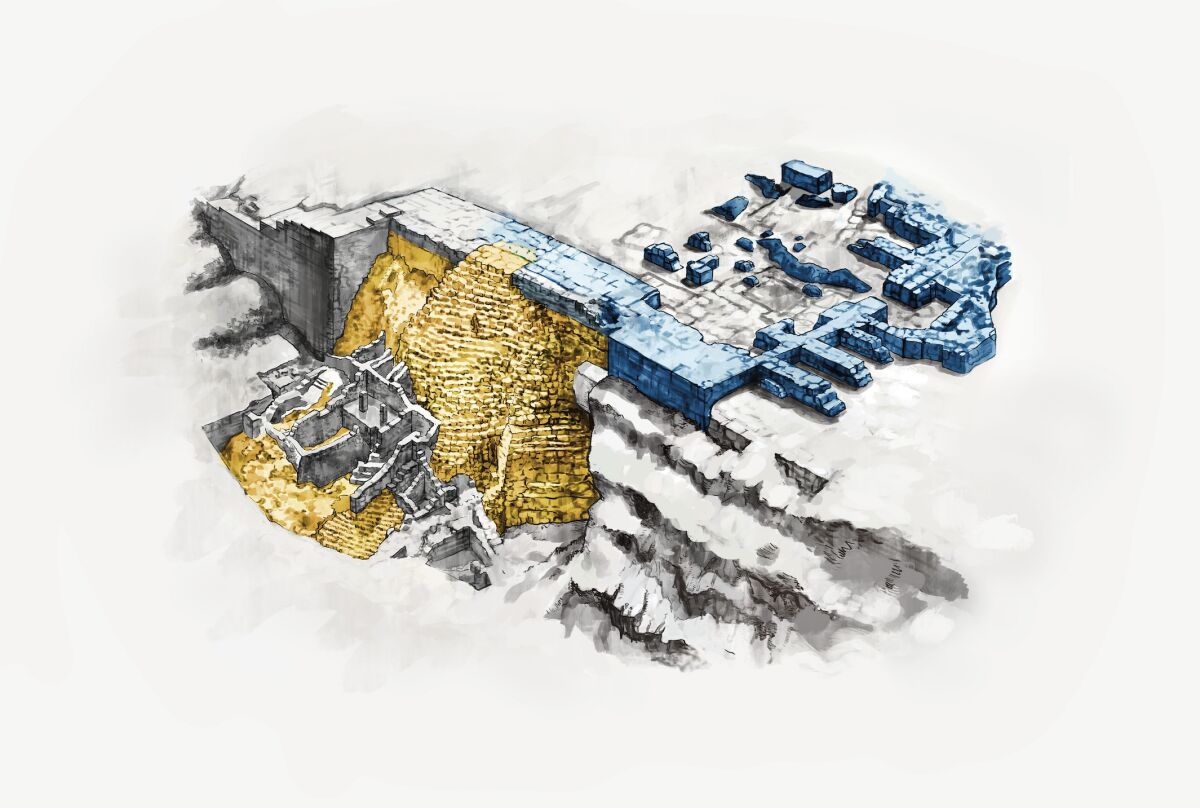

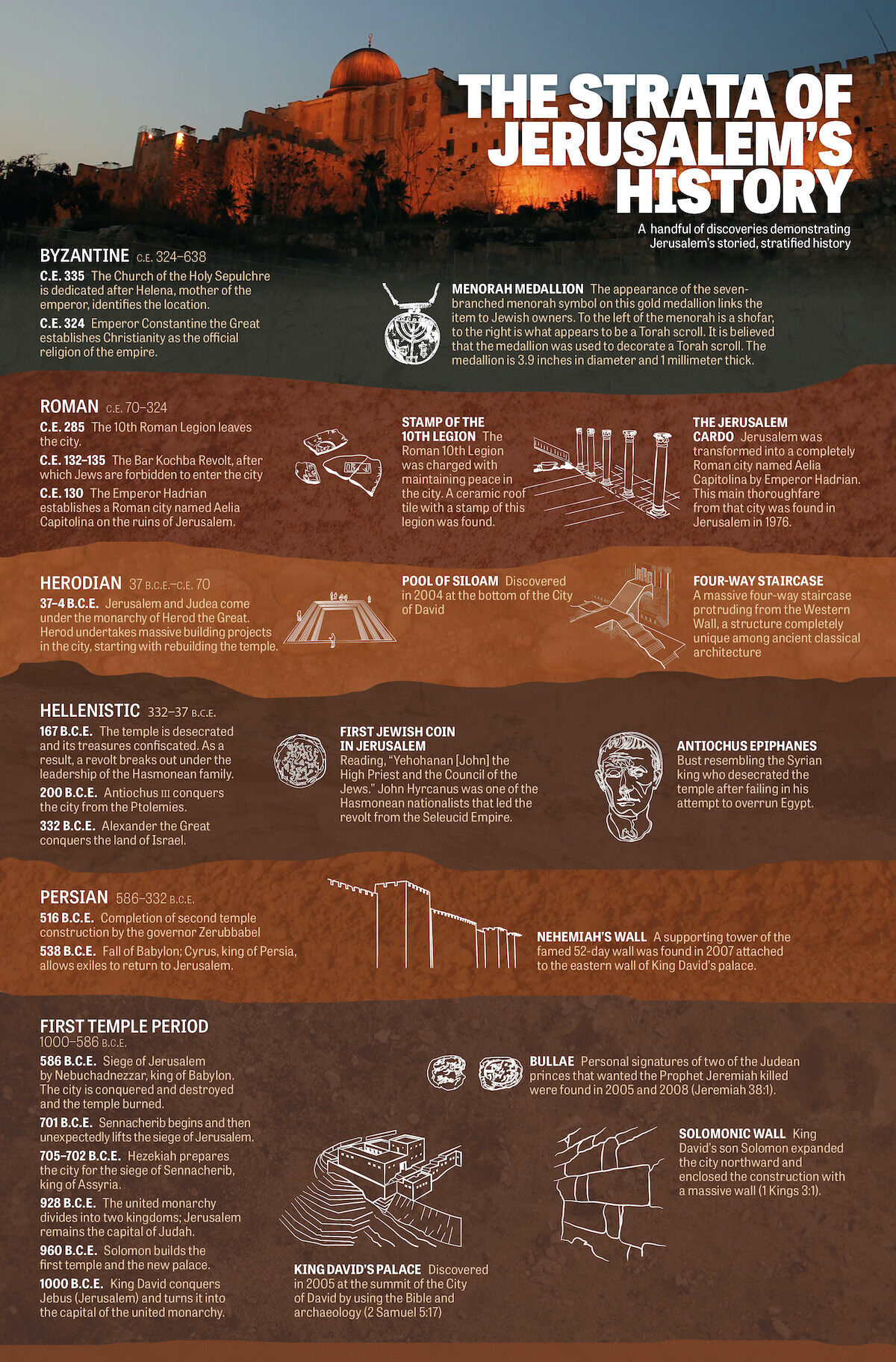

More recent cases in point could be given, such as the Tel Dan Stele (discovered in 1993). But it’s not just the inscriptions—even more consequentially, it’s the architecture. Take the Large Stone Structure—“David’s palace”—excavated by Dr. Eilat Mazar and dated to circa 1000 b.c.e.—the very end of the Iron i/start of the Iron iia period. Yet holding to a Velikovskian timeline, with its aforementioned stratigraphical implications, catapults this structure centuries later. For example, the material found within the strata immediately post-dating and abutting it contained remains relating to Sheshonq i, the late 10th-century b.c.e. pharaoh identified with Shishak (per standard chronology). Following Dr. Hoeh’s original scheme laid out in the Compendium, however, would catapult this structure into the equivalent of the Persian period.

The problems only continue to compound, with later Iron Age constructions developing in and around the Large Stone Structure and associated Stepped Stone Structure, containing the inscriptions of later biblical figures—the bullae (seal stamps) of princes, scribes, priests. These include the names of “Jehucal, son of Shelemiah,” “Gedaliah, son of Pashur,” “Gemariah, son of Shaphan,” “Azariah, son of Hilkiah” and “Nathanmelech, Servant of the King.” These nine individuals all fit with their corresponding biblical counterparts on the scene during the seventh-sixth centuries b.c.e.—found within strata belonging to the end of the Iron iib period (sometimes subdivided as Iron iic, or Iron iii). Yet if the earlier Large Stone Structure and Stepped Stone Structure is effectively redated to the Persian/early Hellenistic period, this would put these figures, and the stratum in which they were found, even later. Forget about coming up with another “Ahab” and “Jehu” to make the chronological system work—it would require explaining the coincidental appearance of a Jehucal, Shelemiah, Gedaliah, Pashur, Gemariah, Shaphan, Azariah, Hilkiah and Nathanmelech during the equivalent of the Early Roman period!

These are just the discoveries from one comparatively small archaeological area on the northern end of the City of David. Numerous more examples could be given—examples fitting directly with the standard chronological layout of history, yet diametrically opposing the Velikovskian, thus requiring labyrinthine explanations of reconciliation from proponents of the latter.

Stratigraphical Gymnastics

As someone working in the field, I can’t emphasize this point enough—particularly with the clear stratigraphical representations in Jerusalem. Our excavations have taken us through clear Islamic strata—including the prominent Umayyad palaces, replete with all the classic Islamic glazed pottery, inscriptions and ornate oil lamps. Underneath this, the Byzantine strata—including a burgeoning neighborhood, monastery and all the related cultic items and mosaics. Underneath this, the Late Roman strata—with the definitive oil lamps, legion tiles, depictions of gods, goddesses and erotica. Underneath this, the Early Roman strata—including late second temple period ritual baths, temple-related artifacts and inscriptions in the classic square script of the period. Underneath this, the Hellenistic strata—including Greek inscriptions and implements of warfare, fitting with historically attested battles. Underneath this, the Persian strata—with the classic “Yehud” administrative stamps, classic triangle-impressed pottery types, and even the peculiar dog-burials of this period. Underneath this, a short-lived Babylonian period stratum—including thick destruction remains, masses of arrowheads, and seals bearing Babylonian iconography. Underneath this, the Iron Age strata—including monumental structures, all the classic Iron Age pottery types and inscriptions in the earlier angular, paleo-Hebrew script. Prior to this, for Jerusalem, we have various more piecemeal Bronze Age period remains—including Akkadian tablets (Jerusalem i and Jerusalem ii) written in the lingua franca of late second-millennium b.c.e. Canaan (closely paralleling the Amarna Letters).

The notion of some kind of compacted or blended amalgamation of Iron Age i, iia, iib, iic/iii into the later, upper, stratigraphically separate Persian, Hellenistic and Early Roman periods simply does not work!

The same is true for the notion of transposing the Late Bronze Age into the first millennium b.c.e. Readers will likely be familiar with the academic debate about the strength and power of Jerusalem during the period of David and Solomon based on the dating of Iron iia architecture—the administrative might of which we have argued strenuously for based on the discoveries of Dr. Eilat Mazar and others (this debate primarily concerns the attribution of remains to the 10th vs. ninth century b.c.e.). Yet if we are to pass off all such discoveries, and instead try look for David and Solomon’s Jerusalem—or for that matter, Jerusalem during the time of any of the biblical kings—in what would be the equivalent of the Late Bronze Age, we would come up entirely empty-handed of any structures whatsoever. Famously, this lack of any known architecture from the Late Bronze period (besides individual sherds and a handful of inscriptions) has led to all sorts of debates, theories and controversies as to where exactly the city was located, and its nature during this time.

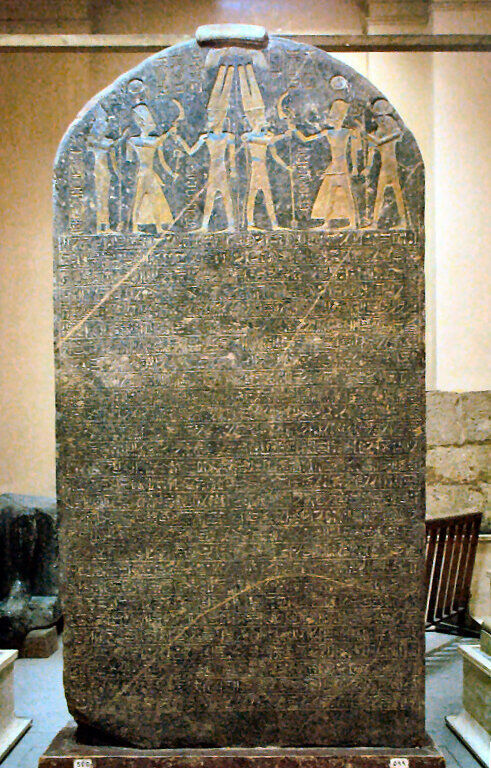

The various other knock-on effects are manifold. Take the Merneptah Stele: Conventionally dated to the 13th century b.c.e., during the reign of Pharaoh Merneptah, this inscription is celebrated as the earliest confirmed mention of the name “Israel.” Yet based on Velikovsky’s timeline, putting Merneptah as one and the same as the sixth-century b.c.e. pharaoh Apries, puts this stele a century and a half after the nation-state of Israel had ceased to exist (late eighth century b.c.e.)!

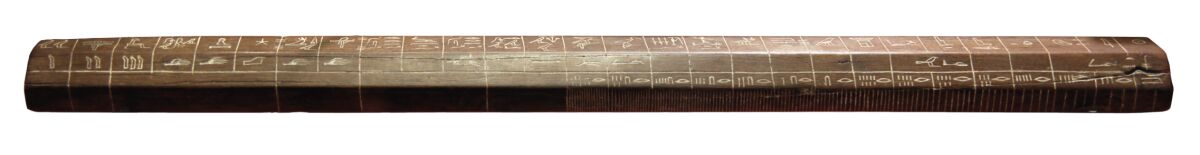

You name the subject. What about simple measurements? What about the fact that the dimensions of particular earlier, Iron iia structures conform to the longer royal cubit, while Iron iib/iii structures utilize the shorter cubit—each conforming to the biblical account of the use of such measurements during these specific periods? And what about the fact that structures within the territory of the northern kingdom of Israel, during the Iron iib, began to reflect a particular use of the unique Assyrian cubit—right around the time of Assyrian conquest and hegemony? Under Velikovskian models, this all requires explaining away in shifting around such periods and ages entirely.

Or what about the use of iron? As outlined by Dr. Hoeh, down-dating the Iron Age into the late first millennium b.c.e.—the Iron i period conventionally beginning circa 1200 b.c.e. and the Iron iia (circa 1000 b.c.e.) marking the point in which iron surpassed bronze as the metal of choice in the Levant—and then continuing the Bronze Age through the biblical kingdom period—opens up a Pandora’s box of issues. Already there is debate aplenty about the level of iron work in the second millennium b.c.e., during the Bronze Age, based on biblical mentions of iron during this time. Yet even here, for the pre-monarchical period, biblical mentions of ironwork are relatively sparse, fitting with the picture of history at the time—when bronze work was predominant and ironwork was at least a comparatively fledgling practice. But to continue the Bronze Age right on into and through the biblical kingdom period, where biblical mentions of mass iron production appear—a time, for example, in which “David prepared iron in abundance … iron without weight, for it is in abundance”? (1 Chronicles 22:3, 14).

It seems that Dr. Hoeh finally lost faith in Velikovskian chronology following a protracted dispute between Dr. Velikovsky and Prof. William Stiebing (who wrote at length countering the theories). Hoeh continued, in his lecture: “William H. Stiebing wrote a criticism of Velikovsky’s revised chronology, which could be in part equally attributed to anything I have written in the two volumes of the Compendium pertaining to Egypt and Mesopotamia. … He made the evidence clear enough that, when Velikovsky answered the material, there is no doubt that there was no solid answer … there was no possible way to reconcile the reconstruction of history as Velikovsky had given it.”

Opinions in Collision

When I first read Ages in Chaos, I was somewhat surprised. Given the notoriety of Velikovsky’s publication, I was ready to have my view of history challenged, expecting it to be a compelling study highlighting difficulties with more mainstream chronologies. I was a bit surprised with how little material evidence and facts were presented, and how much analysis was based on assumption, conjecture and extrapolation.

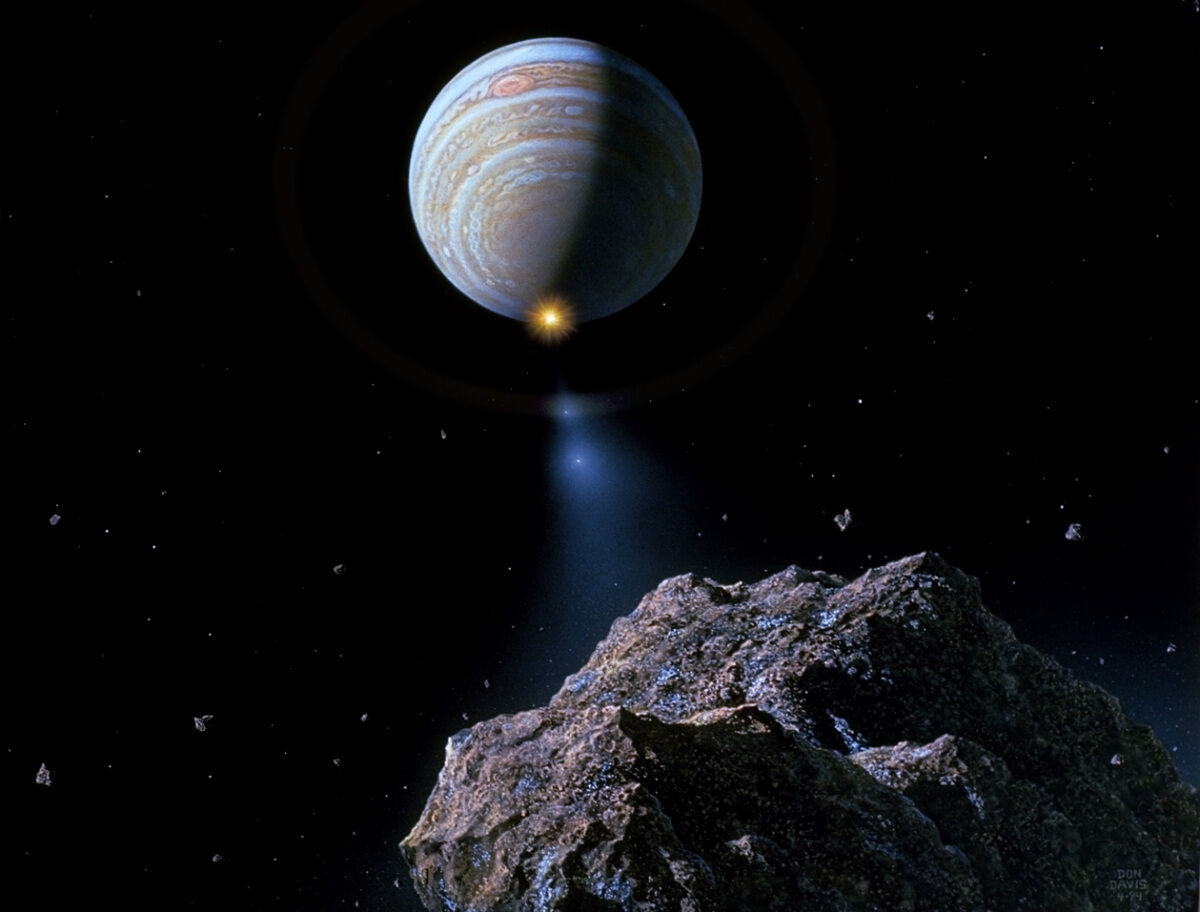

It’s also worth noting that the Ages in Chaos series presents the tamer of Dr. Velikovsky’s views. His other major publication, Worlds in Collision (1950), proposes rather surprising interplanetary explanations for the events of mythologies and biblical history within his chronological framework. For example, he proposes that in the 15th century b.c.e. the planet Venus was essentially birthed—ejected out of the planet Jupiter as a comet—passing near the Earth and causing various rotational catastrophes that resulted in the plagues of Egypt (even the falling of manna from heaven—“ambrosia … from the clouds of Venus”). Another half-century later, he posits that the planet-comet passed close by Earth again, causing Earth’s rotation to stop—resulting in the “long day” of Joshua.

Velikovsky went on to propose that around 700 b.c.e., Mars—having been displaced by the rogue Venus—likewise passed close to Earth, causing further disturbances that resulted in the biblical events described during the reign of Hezekiah, including the annihilation of Sennacherib’s army at Jerusalem, and the retreat of the shadow on the sundial of Ahaz as a miraculous sign of the king’s healing.

In the academic world, the publication of such notions caused a furor. The aforementioned Professor Stiebing summarized the affair:

The publication of Worlds in Collision produced a storm of controversy, especially in the scientific community. Velikovsky’s theories were ridiculed by many leading scientists, and a few even tried to have the book banned from libraries and bookstores. Of course, these unscientific and undemocratic attacks made Velikovsky into something of a martyr. His followers—and sometimes the press—compared him to Galileo, Einstein, Newton, Darwin, Freud and other original thinkers whose theories had been attacked because they violated the dogmas of their times.

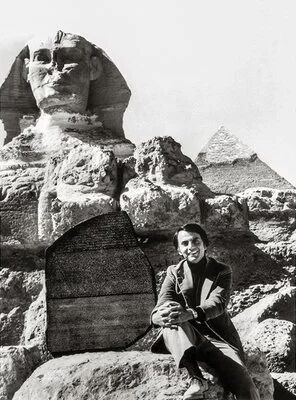

One of the most prominent figures to tackle the controversy was the famous astronomer and science communicator Carl Sagan. He wrote an article in the January-February 1980 Biblical Archaeology Review titled “A Scientist Looks at Velikovsky’s Worlds in Collision,” demonstrating the absurdities of the events proposed by Velikovsky. Yet he likewise placed blame on the modern scientific community in its handling of the affair. “To the extent that scientists have not given Velikovsky the reasoned response his work calls for, we have ourselves been responsible for the propagation of Velikovskian confusion.” Still, “scientists cannot deal with all areas of borderline science.”

Sagan concluded by pointing out Velikovsky’s explanations as requiring more faith than the Bible—that his comet-planet Venus had all but taken the place of God Himself. “[I]s the evidence not better for the God of Moses, Jesus and Muhammed than for the comet of Velikovsky?”

Yet in a sense, Velikovsky’s deference to naturalistic explanations—as unlikely as they may sound—is unsurprising. For Immanuel Velikovsky was, ironically, an atheist.

Where Does That Leave Us?

In light of new discoveries and a reassessment of the old, Dr. Hoeh eventually came to reject Velikovskian chronology and adopt the standard chronological model of history, fitting to it biblical figures. For example, regarding the identity of the pharaoh of the Exodus: In his original Velikovskian model, Dr. Hoeh had proposed Merenre Nemtyemsaf ii (traditionally dated to the 23rd century b.c.e. and down-dated to the early 15th century b.c.e.). In switching to the standard New Kingdom Period model, Dr. Hoeh initially proposed Thutmose ii, maintaining an Exodus during the early 15th century b.c.e., before finally settling on a mid-15th-century b.c.e. Exodus and a favorite among many conservative high chronologists—Amenhotep ii (i.e. “Notes Regarding Reigns of Kings,” 1983).

As for the much earlier historical periods: Velikovsky’s down-dating of Egyptian history—conventionally held to begin just prior to 3000 b.c.e.—by up to 600 years has been a key attraction for those seeking to harmonize such early periods with the timeline for the biblical Flood. This is a thorny question that gets into multiple topics, disciplines and debates, among them the different biblical chronologies for this event found in the Masoretic, Septuagint and Samaritan texts; whether the Flood was a “global” or “regional” event; and the nature of civilization on either side of the biblical Flood (often articulated with the question: “Did the pyramids survive the Flood?”).

This is an enormous topic for another article. Suffice it to say we do not have before us an either-or situation, in which we are forced to choose Velikovskian chronology to “make it fit” (or “relieve pressure,” in the words of Dr. Hoeh). As stated above, our material on this website does follow conventional chronology back through the second millennium b.c.e.—prior periods caveated, which are significantly more murky (and outside the realm of most of our material). As far as very earliest Egyptian history goes, I believe there is room for debate about the merits of down-dating. Yet as we have seen, this is not a through-line that cuts right across millenniums of Egyptian, Mesopotamian and Levantine history, right on through and even beyond the Hellenistic period. That much is clear. While I certainly believe chronological debate can be had in the realm of decades, from the New Kingdom Period onward, this history is now otherwise well enough attested to preclude debate about centuries (David Rohl’s New Chronology notwithstanding)—and certainly not more than half a millennium.

In the end, as well intentioned as Velikovksian chronology may be—as well worded as it, in various forms, may appear on paper—it is just that, a scheme that “works” only on paper—not in practice—not in the field.

Article updated 26/08/25.

Read More: The Curious Conflict Between Radiocarbon Dating and Early Egyptian Chronology