“I don’t believe in carbon-14 dating at all,” said Egypt’s premier Egyptologist Dr. Zahi Hawass on a recent viral Joe Rogan podcast. “And it’s not working in Egypt until today.” The 78-year-old Hawass, who is generally regarded as representative of the mainstream in Egyptology, surprised a number of commentators in the archaeological community with his comments.

Actually, the assertion is not surprising and carries with it baggage from decades-old debates and disagreements about the very viability of radiocarbon dating in Egyptology—debate that featured prominently in the first part of Hawass’s 57-year career.

Archaeologist Prof. Gabriel Barkay once famously said, “Carbon-14 is like a prostitute. Given the margin of error, radiocarbon allows everyone to argue the position they already hold.” Not so, however, for earliest Egyptian history—at least not originally. And it still proves a tripping point—hence Hawass’s sentiments.

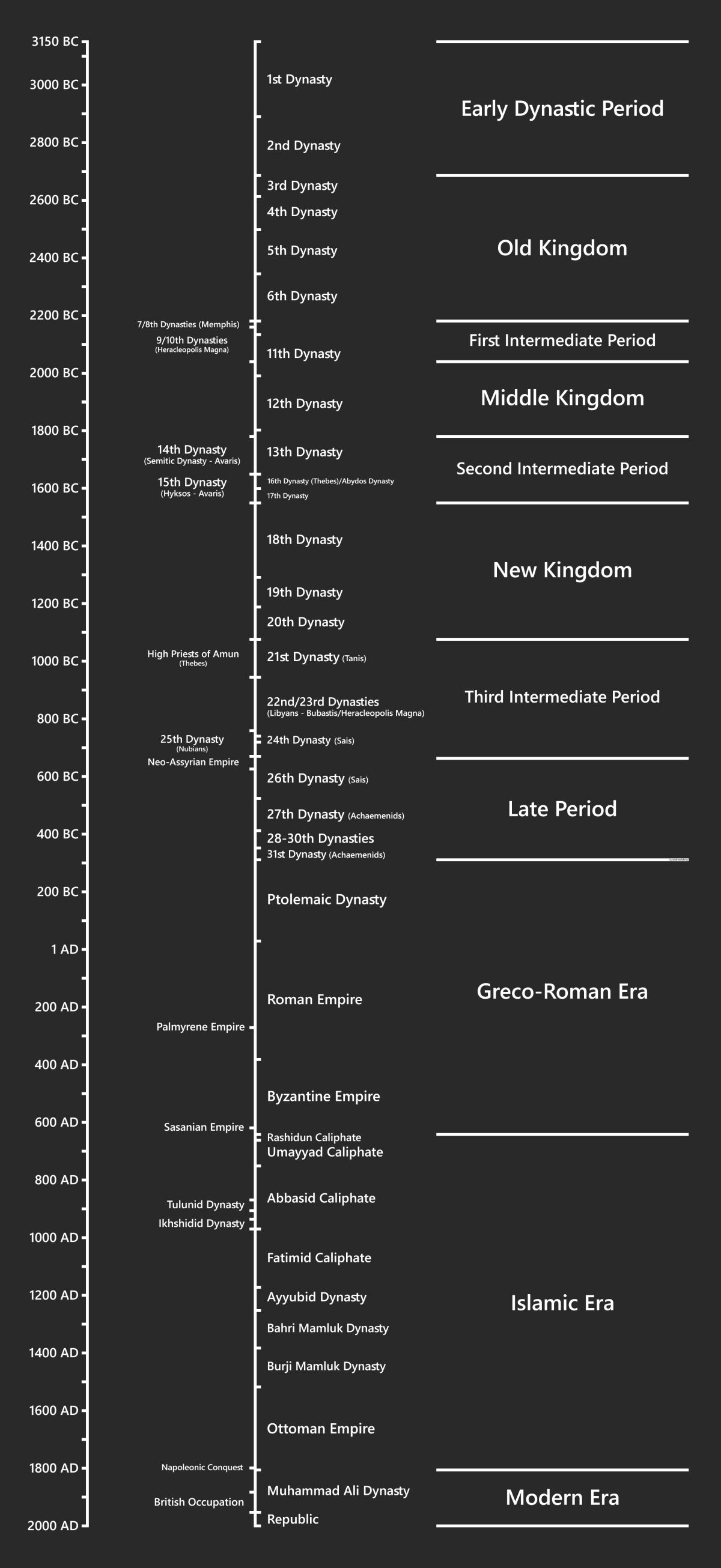

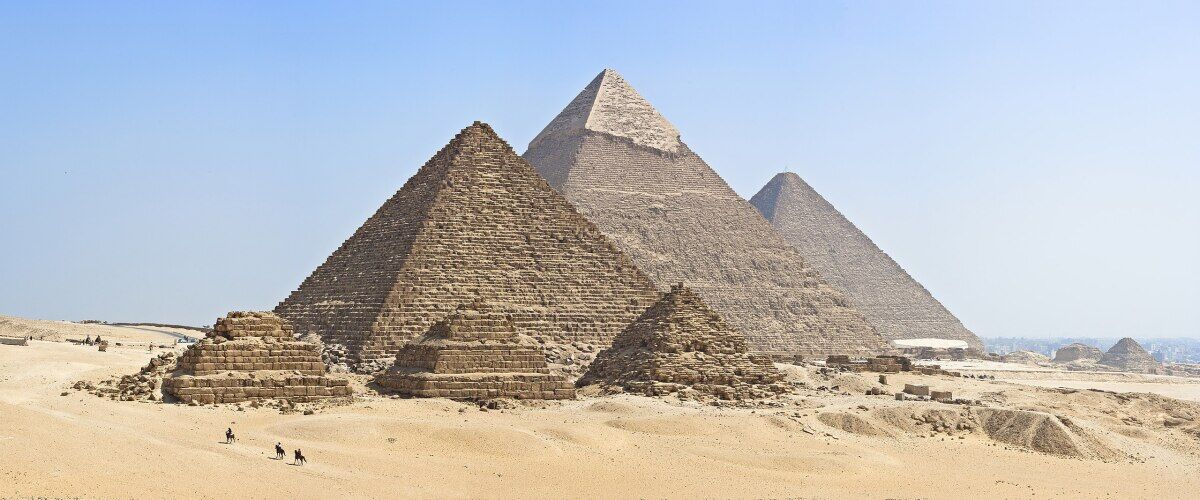

Radiocarbon dating originally and consistently provided centuries later dates for Egypt’s earliest dynastic history, conventionally held as beginning around 3000 b.c.e. and spanning throughout the third millennium b.c.e. This was not a through-line for all Egyptian history, however—radiocarbon findings from circa 2000 b.c.e. (the Middle Kingdom Period) onward generally did match standard Egyptian chronology—but this dissonance did apply specifically to Egypt’s earliest periods, especially the third millennium b.c.e.’s Early Dynastic, Old Kingdom and First Intermediate Periods.

When it comes to the subject of radiocarbon dating and the Bible, this is often unfortunately portrayed—especially for earlier periods—as “religion” vs. “science,” with the former seen as reflective of much younger dates than the latter. In this debate about earliest Egyptian history, however, we have a scenario almost comically flipped on its head—with radiocarbon invariably providing far younger dates for Egyptian history, in juxtaposition to the early chronology so firmly established by the Egyptological establishment.

As it stands currently, we know who muscled into victory on this debate. But what if we went wrong?

Founder’s Faith—Fractured

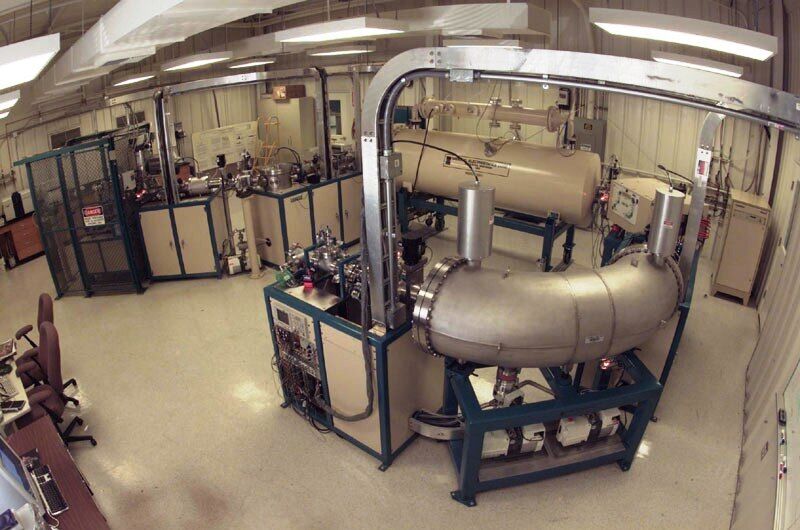

The radiocarbon dating method—also known as carbon dating, carbon-14 dating, C-14 or 14C—was developed by American physical chemist Prof. Willard Libby in the 1940s (read more about the workings of radiocarbon dating here). In proving the viability of his new dating method, Libby originally tested it against items that were already considered securely dated in the historical record. In a 1960 Nobel Prize acceptance lecture (which he was awarded for his development of the technology), Libby highlighted the immediate issue his team came up against: the ambiguity of historical ages. “You read statements in books that such and such a society or archaeological site is 20,000 years old,” he said. “We learned rather abruptly that these numbers, these ancient ages, are not known accurately.”

“The first shock Dr. Arnold and I had was when our advisers informed us that history extended back only to 5,000 years. … [I]n fact, it is at about the time of the First Dynasty in Egypt that the first historical date of any real certainty has been established,” he stated.

Yet Libby’s acceptance of even this as fact would soon change.

“Willard F. Libby, founder of radiocarbon dating, after considerable examination of the available evidence in 1963, decided that Egyptian historical events thought to date 5,000 years ago were in error on the order of five centuries,” wrote Ronald D. Long in his 1976 article “Ancient Egyptian Chronology, Radiocarbon Dating and Calibration” (emphasis added throughout). “He [Libby] observed that the earliest astronomical anchor point is at 4,000 years ago, but concluded that all older Egyptian dates were imprecise. There were other geophysicists who agreed with Libby, in that the problem resided with historical chronology prior to the Middle Kingdom [circa 2000–1650 b.c.e.].”

The late Dr. Herman Hoeh, an employee of our namesake, summarized the same in a 1977 lecture at Ambassador College:

Dr. Willard Libby of the University of California at Los Angeles developed the method of radiocarbon dating. It seemed to defend some areas of history as traditionally interpreted. In other areas it did not. …

[M]any radiocarbon dates for the Old Kingdom of Egypt were apparently too young for historians. … [R]adiocarbon dates of the Old Kingdom in Egypt were falling in the 24th to the 20th centuries. These dates were impossibly young for traditional Egyptian history.

Libby wrote in his 1963 Science article “Accuracy of Radiocarbon Dates”:

The data in Table 1 are separated into two groups—Egyptian and non-Egyptian. This separation was made because the whole historical Egyptian chronology is interlocking and subject to possible systematic errors, whereas other historical dates are presumably more independent of each other and therefore relatively free of such errors. …

These plots of the data suggest that the Egyptian historical dates beyond 4,000 years ago [i.e. 2000 b.c.e.] may be somewhat too old, perhaps five centuries too old at 5,000 years ago, with decrease in the error to 0 at 4,000 years ago. In this connection it is noteworthy that the earliest astronomical fix is at 4,000 years ago, that all older dates have errors, and that these errors are more or less cumulative with time before 4,000 years ago.

It’s important to note two things here: First, radiocarbon data did generally serve to corroborate the standard model of Egyptian history/chronology back to circa 2000 b.c.e.; and second, all dating prior became exponentially worse against the standard model, to the tune of five centuries.

Impasse

In fact, it was even worse—with extreme examples of discrepancies of up to seven-plus centuries (as noted by Long in a series of tables at the end of his work). Remains associated with Hor-Aha, for example—recognized as the second pharaoh of Egypt’s First Dynasty—were dated up to as late as the mid-24th century b.c.e., while Egyptian chronology had him on the scene in the early 31st century b.c.e. Remains relating to Den—great-grandson of Hor-Aha—were dated up to as late as the mid-22nd century b.c.e., while Egyptian chronology had him on the scene during the mid-30th century b.c.e. And certain radiocarbon dates for Djoser—a pharaoh of the Old Kingdom’s Third Dynasty, famed as the very first of the pyramid-builders—were returning numbers as low as the late 21st century b.c.e., while Egyptian chronology had him on the scene during the mid-27th century b.c.e. Long wrote:

Archaeological, geophysical and methodological explanations for the discrepancies were investigated. An answer to the difficulties was not forthcoming. [British archaeologist] Sir Max Mallowan expressed concern over the possibility that the Egyptian dynastic structure, the very basis for the chronology of the ancient Near East, would have to be radically revised if radiocarbon continued to influence dating of the third millennium b.c.

Such propositions of a younger Egyptian chronology, to the tune of multiple centuries, were anathema to the Egyptological establishment, and the debate was at an impasse. Libby and his colleagues believed the formulation of Egyptian history prior to the Middle Kingdom Period was in error, artificially extended far earlier than reality; Egyptologists, contrarily, dismissed the carbon-dating method as useless and irrelevant to the study of earliest Egyptian history—for whatever unknown reason, simply not working. The established dynastic structure and chronology, after all, was deemed secure—carbon dating should be bent to match. In the words of Prof. Michael Dee, though the “accuracy of radiocarbon dating in Egypt has remained a source of contention for many decades … Egypt is exceptional because its written records are precise enough to challenge the scientific method as far back as the third millennium b.c.” (Radiocarbon and the Chronologies of Ancient Egypt).

A reason had to be found—something to fit radiocarbon data with already-established Egyptian chronology. Eventually, a solution was found, making, in the words of Dee, “Egyptian historical chronology … integral to the establishment of the radiocarbon method” as it is today, with the calibration of dates that it outputs.

What was that solution?

Bring Out the California Bristlecone

The “solution” to this problem was found in the 1970s, essentially calibrating carbon dating to match the traditional chronology of third millennium b.c.e. Egyptian history using California bristlecone pine-derived data.

Dr. Hoeh, in his aforementioned lecture, summarized this “evaluation of bristlecone pine dating on radiocarbon dates.” The world’s longest-living trees found in the “forest in the White Mountains of California was indicating that prior to the time of Alexander the Great, the level of radioactivity had been greater”—thus leading to a new radiocarbon chronology “corrected by the bristlecone pine curve.”

Long explains the history of research:

By 1969, [Prof. Hans] Suess had measured the amount of C-14 in dendrochronologically dated tree-rings of bristlecone pine (Pinus aristata) from the White Mountains in California, U.S.A. Bristlecone pine tree-rings were counted, and assigned true or calendar ages, parallel to the antiquity of Egypt, before they were dated by radiocarbon. From the data, Suess created a calibration curve which plotted the true ages of tree-rings against the radiocarbon age of the dendrochronologically dated tree-rings. Thus, the Suess curve shows the relationship of the actual amount of C-14 in the atmosphere of the White Mountains for any given year from the third millennium b.c. onwards, to the amount of C-14 expected on the pre-Suess or original Libby radiocarbon theory. …

Geophysicists concluded that the quantitative difference between true age, and C-14 age of Pinus aristata tree-rings was on the same order of error as that between astronomical ages, and C-14 dates for Egyptian material. Consequently, just as a tree-ring with a calendar age of 3000 b.c. rendered a carbon-14 age of 2363 b.c., so an Egyptian artifact assigned an age of 2363 b.c. by C-14 would have the same quantitative relationship between true age, and C-14 age as that related by bristlecone pine. The object relating a conventional radiocarbon age of 2363 b.c. is not, in fact, that young. Calibration with the Suess curve, however, places the age “correctly” at 3000 b.c.—but only if the object being dated came from an environment where the geophysical phenomena were the same as those in which the bristlecone pine grew.

This, then, provided an answer Egyptologists were looking for—how there could be such an immense discrepancy in “true” Egyptian historical dates and radiocarbon dates. Certain fundamental assumptions built into Libby’s science of radiocarbon dating were shown to be in error.

Problems

Yet in all this, in the words of Long, problems only “were made to appear to be reconciled.” Again, this method applying in theory—but “only if the object being dated came from an environment where the geophysical phenomena were the same as those in which the bristlecone pine grew.” And Egypt is, of course, an immensely different environment. Libby’s associate, Dr. Rainer Berger, cautioned that “bristlecone pine wood exposed at high elevations may suffer in situ production of radiocarbon based on its nitrogen content over long periods of time.”

“Search for trees of an age equal to bristlecone pine which could function as a check for the Suess measurements have failed,” Long wrote. “Consequently, the curve for correcting all radiocarbon data rests upon a single species which is not without its own suspect characteristics.” To this end, while no other tree species was able to match the longevity of the California bristlecone, younger data points from other varieties revealed centuries-worth of radiocarbon discrepancies. Samples from New Zealand kauri (Agathis australis), for example—dating back to around 1000 c.e.—demonstrated rings “on an average, 200 years older than the Northern Hemisphere results with bristlecone for the same period.” He continued:

Since there is an appreciable difference only 950 years ago, there is no way of predicting the age gap between kauri and bristlecone for the same years during the eras of importance with relation to the Egyptian past. … The difficulty resides in an attempt to impose a calibration based on a tree found in the environment of the White Mountains on Egypt. While the Pharaohs ruled there were no tree-rings growing in Egyptian soil which are alive today and can be dendrochronologically dated.

“This demolishes the theory on which the Suess curve rested,” wrote Long.

Still, for cross-checking periods of such antiquity, bristlecone pine was all that was available. And after all, Egyptologists were unanimous on Egyptian history, pre-2000 b.c.e.—prior to the Middle Kingdom Period. In the words of Rainer Berger in 1970—still, at this point, evidently struggling with the discrepancies between Egyptian chronology and radiocarbon data: “From the point of view of most modern Egyptologists the sequencing of events during the Old Kingdom is quite certain,” despite the lack of outside synchronisms and astronomical anchors for this earlier period (which do exist for later periods). “Yet the lack of unanimity among the knowledgeable with respect to the duration of individual regnancies or other reasons cannot account in their aggregate for the size of the discrepancies.”

“[N]o major differences exist between a radiocarbon-based chronology using the 5730-year [Libby] half life and the historically accepted dates within the degree of archaeological resolution of this study up to the time of Sesostris iii [19th century b.c.e.],” he wrote. It was only for periods prior, “[f]rom this point on, [that] the bristlecone pine calibration curve of Suess” need be applied, “approximat[ing] the presently recognized historical chronology of what amounts to mostly the time of the Old Kingdom.” Even still, with this pine calibration curve, the data “does not exactly follow the historical chronology” (“Ancient Egyptian Radiocarbon Chronology”).

In the years and decades since, multiple explanations have been given for the presence of such differences in data, not only in comparing the Northern Hemisphere to the Southern, but also island environments to landmasses, altitudinal differences, etc. As it stands now, radiocarbon dating has become so calibrated and re-calibrated as to be almost unrecognizable to Libby’s original creation.

Yet in all this, for all the wrestling with radiocarbon data, the one rock has been early Egyptian chronology itself. Or was it ever such a cornerstone after all?

Ian Onvlee described the increasingly widening gap of chronological issues prior to Egypt’s New Kingdom period (beginning mid-16th century b.c.e.) in his article “The Great Dating Problem: Improving the Egyptian Chronology.” He wrote:

We are silently expected to include this factor of uncertainty in any offered history of Ancient Egypt. Yet Egyptologists usually fail to stress this embarrassing fact …. [A]lthough most people accept a “Conventional Egyptian Chronology” for convenience, it is only one of the many possibilities …. Professor Heinrich Otten has called the current scholarly consensus a “rubber chronology” that could be stretched or shrunk, by arbitrarily established lengths of coregencies between rulers and even overlapping dynasties …. The current consensus has become an inflexible tradition, even if admitted to be incorrect.

Onvlee, for his part, argues for a revision of Egyptian chronology as centuries older. But a centuries younger Egyptian chronology, reflective of the earlier radiocarbon data? No one argues for such a thing.

Right?

Enter the ‘Father of Egyptology’

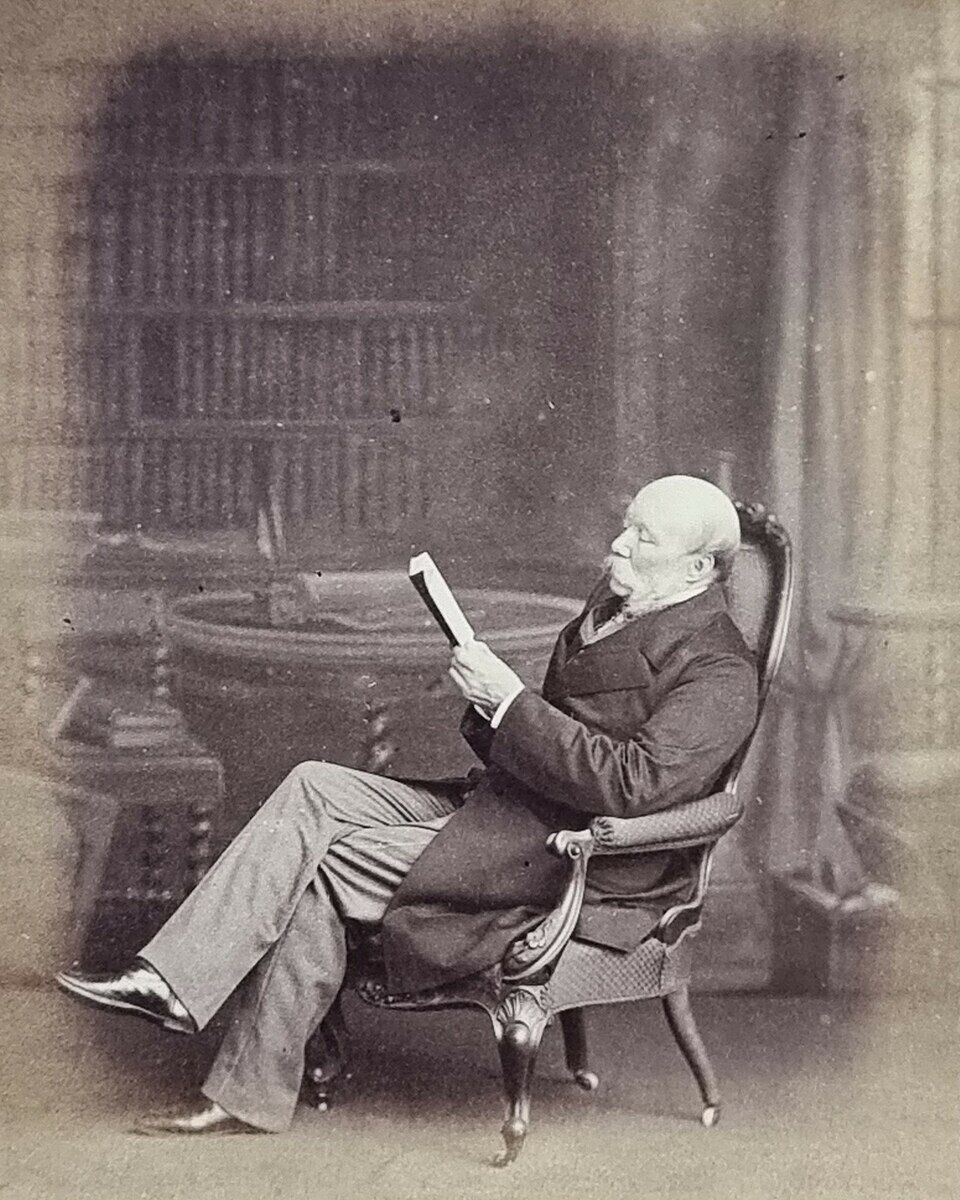

The much younger radiocarbon data indeed proved shocking to Egyptologists. It would not have been so, however, to arguably the greatest Egyptologist of all time: Sir John Gardner Wilkinson (1797–1875).

Wilkinson—sometimes referred to affectionately as the “Father of British Egyptology” (and even the “Father of Egyptology” in general)—was an antiquarian and explorer with an impressive biography, with some going so far as to credit him as the decipherer of hieroglyphics, before the famous work of Jean-François Champollion (given Wilkinson’s ability to already deduce the names of rulers, and even his critique of Champollion’s work). Wilkinson was unique among scholars at the time in his residing in Egypt for a significant period of time—a total of 13 years—studying and excavating sites up close and in person, rather than studying the subject matter from abroad (Champollion, in contrast, spent two years in Egypt). His magnum opus was his five-volume Manners and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians, first published in 1837 and republished in abbreviated form a decade later. While he wrote extensively on ancient Egypt, his publications spanned an immense genre, leading to issues in categorizing his work.

In Volume 1 of Manners and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians, Wilkinson includes his chronology of Egyptian history. Notable and ahead of its time was his placement of Egypt’s New Kingdom Period (18th Dynasty) onward—beginning with its initial pharaoh, Ahmose i, in 1575 b.c.e. (Modern high chronology, for example, begins his reign circa 1570 b.c.e., with lower chronology a couple of decades later.) Yet even more striking is the fact that he began Egypt’s earliest history with the accession of its founder, Menes (predecessor of the aforementioned Hor-Aha), as late as 2320 b.c.e. (Even this, he notes as a slightly earlier revision to his original proposal, that Menes began to reign in the 2200s b.c.e.)

Even more striking is the fact that his 19th century peers were giving immensely higher dates compared to even that accepted today. Five years after Wilkinson’s publication, Champollion published his own chronology, beginning the reign of Menes at 5867 b.c.e.—more than 3,500 years earlier. Eight years later, the German scholar C.C.J. Bunsen sent his reign over 2,000 years back in the other direction, to 3623 b.c.e. Three years after this, Menes’ reign was redated by archaeologist R.S. Poole nearly 1,000 years later again—2717 b.c.e. Within five years of Poole’s chronology, the pendulum swung in the other direction, with a date more than 1,000 years earlier provided by Prussian Egyptologist Karl Lepsius—3892 b.c.e. Three years after that, in 1859, Menes’ reign was dated some 1,500 years earlier again, to 4455 b.c.e., by German Egyptologist Heinrich Karl Brugsch. By 1869, it was back down to 4157 b.c.e., per German Egyptologist Franz Joseph Lauth; two years later, thanks to the work of French scholar Auguste Mariette, the date was pushed back again 1,000 years to 5004 b.c.e.

In 1878, American academic James Strong brought the debate almost full circle once again, offering a much younger date for Menes of 2515 b.c.e. Yet 11 years later, in 1887, British Egyptologist Sir Flinders Petrie sent Menes back again more than 2,000 years in history, to circa 4777 b.c.e. Today? General consensus hovers somewhere around 3000 b.c.e.

In less than two centuries of Egyptological scholarship, the date of Menes and his “founding” of dynastic Egypt has shifted wildly, across a span of more than 3,500 years.

While a centuries-earlier timeframe to Wilkinson’s is preferred by modern scholars—in large part, relying on varying interpretations of the work of the third-century b.c.e. Egyptian priest-historian Manetho for chronological reconstructions—despite a tendency to scoff at younger dates, it is notable that the conventional timeframes are still technically closer to Wilkinson’s than to those of most of his contemporaries. And Manetho aside (whose work is fraught with difficulty in transmission and interpretation), Wilkinson’s date at least did agree more generally with the timeframe accorded by the first-century c.e. historian Josephus, who noted “all the kings of Egypt from Menes … until Solomon, where the interval was more than one thousand three hundred years” (Antiquities of the Jews, 8.6.2). With Solomon’s reign anchored in the mid-10th century b.c.e., this would put Menes—based on Josephus’s statement—on the scene in the 23rd century b.c.e.

In the end, this isn’t to say that the original radiocarbon dates of the likes of Libby and Berger, and the Egyptian chronologies of the likes of Wilkinson and Strong, are necessarily correct; nor to say that the calibrated radiocarbon dates for the third millennium b.c.e., as they stand today, are necessarily wrong. If anything, it is a check against our perceived certainties—i.e. about Egyptian chronology or radiocarbon data as beyond reproach—each often mistakenly seen as unbiased checks on our understanding of the past.

In the case of C-14, in a sense, Barkay’s words quoted in the introduction still stand. For at the end of Long’s article, he concludes rather dismally:

“In general, C-14 has not altered our reconstruction of history in any form.”